Ilo Convention No 169

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bo Lengre Hjemme Økt Selvhjulpenhet Og Større Trygghet

Vær Bo lengre hjemme økt selvhjulpenhet og større trygghet Iver O. Sunnset Prosjektrådgiver IKT Helse VarIT Om Værnesregionen VR som samarbeidsprosjekt ble igangsatt i 29.10.2003. Formålet: ”Å utvikle tettere samarbeid og samhandling, for å sikre et godt service og tjenestetilbud.” Deltaker-kommuner er Stjørdal, Selbu, Tydal, Malvik, Meråker og Frosta IT-samarbeidet startet for fullt i 2004 Værnes regionen er ett laboratorium for esamhelse og velferdsteknologi i fylket Ambisjoner om å etablere felles driftssentral for helseløsninger i hele NT, og hvorfor ikke i regionen? Også velferdsteknologi. Bo lengre hjemme • Kommunene i Værnesregionen har stort fokus på hvordan bruk av informasjons-teknologi kan bidra til å effektivisere den interne forvaltningen, og samtidig høyne kvaliteten på våre tjenester. • Dagens varslingssystem for hjemmeboende og på sykehjem dekker ikke behovet for trygghet og sikkerhet. Velferdsteknologi er ett av flere tiltak. • Værnesregionen velger framtidsrettede løsninger ved bruk av velferdsteknologi, både for å skape trygghet rundt beboere og deres pårørende, men også tilrettelegge for et sikkert og effektivt tjenestetilbud. Mål: • Tilby en trygghetsskapende løsning som fanger opp hjelpebehovet, og aktiverer rett hjelp til rett tid. • Identifisere og kartlegge eventuelle barrierer med bruk av velferdsteknologi. • Involvere leverandører i utvikling av helhetlig systemløsninger som understøtter behovene. • Utarbeide planer for kompetanse og rutiner, samt sørge for nok kunnskap til sikker bruk og drift. Bo lengre -

SKARVAN OG ROLTDALEN Beautiful Highland Valleysand Vast Mountains 2° 3° Skarvan Og Roltdalen National Park Skarvan Og Roltdalen National Park

SKARVAN OG ROLTDALEN Beautiful highland valleysand vast mountains 2° 3° Skarvan og Roltdalen National Park Skarvan og Roltdalen National Park Welcome to one of trøndelag’s largest unspoiled areas of mountain and forest Skarvan og Roltdalen National Park is situated between Neadalføret and Stjørdalsføret and it contains within its boundaries mountain plateaus, wooded valleys and extensive marshy areas. It is an area that has remained untouched by major technological development, such as power trans¬mission lines or roads. Roltdalen is the largest wooded valley in the Sør-Trøndelag region without any roads. The conifer forest here is subject to national interest. The area now defined as national park has been in use for at least 2 000 years. The park therefore contains a broad range of cultural relics such as house footings, ironworks, Sami settlements, pitfalls, traces of copper mines and millstone quarries, tar kilns, hill farm buildings, remote hayfields and old transport routes. Close to Liavollen (ES) 4° 5° Skarvan og Roltdalen National Park Skarvan og Roltdalen National Park In upper Roltdalen (ES) Schulzhytta (ES) EXPERIENCE NATURE THE LANDSCAPE AND GEOLOGY Plenty of hiking routes The landscape in Skarvan og Roltdalen National Park is With its forests, mountains, lakes and marked trails, the varied. The extensive Roltdalen runs southwest through national park is a spectacular hiking area, on foot or by the park. It is covered mainly by spruce forest and large ski. Organised horse-riding tours are also available. areas of bog, while the north is dominated by the vast Skarvan massif, rising to 1,171 metres above sea level. -

The Effects of Power Lines on Ungulates and Implications for Power Line Routing and Rights-Of-Way Management

Vol. 6(9), pp. 647-662, September 2014 DOI: 10.5897/IJBC2014.0716 Article Number: 23B72C447892 International Journal of Biodiversity ISSN 2141-243X Copyright © 2014 and Conservation Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJBC Review The effects of power lines on ungulates and implications for power line routing and rights-of-way management Gundula S. Bartzke1,2*, Roel May1, Kjetil Bevanger1, Sigbjørn Stokke1 and Eivin Røskaft2 1Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, 7485 Trondheim, Norway. 2Institute for Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7491 Trondheim, Norway. Received 14 April, 2014; Accepted 22 July, 2014 Thousands of kilometres of power lines exist and more are planned. Ungulates that range over large areas are likely to encounter power lines, but a synthesis of power line effects on ungulates is lacking. Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) are suspected to avoid power lines up to distances of 4 km. In contrast, some forest ungulates preferentially forage in power line rights-of-way, cleared areas under power lines. We reviewed the factors that possibly influence avoidance and attraction effects of power lines on ungulates, construct a conceptual framework, and make suggestions on how to mitigate avoidance effects through power line routing and rights-of-way management. Power line construction, noise and electromagnetic fields are possible sources of disturbance, while rights-of-way management influences habitat use under power lines. Disturbance and altered habitat use can induce barrier and corridor effects, thereby influencing connectivity. Species-specific effects influence behavioural disturbance and habitat use. We found little evidence for behavioural disturbance of reindeer or forest ungulates under power lines. -

Nye Fylkes- Og Kommunenummer - Trøndelag Fylke Stortinget Vedtok 8

Ifølge liste Deres ref Vår ref Dato 15/782-50 30.09.2016 Nye fylkes- og kommunenummer - Trøndelag fylke Stortinget vedtok 8. juni 2016 sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke fra 1. januar 2018. Vedtaket ble fattet ved behandling av Prop. 130 LS (2015-2016) om sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag og Sør-Trøndelag fylker til Trøndelag fylke og endring i lov om forandring av rikets inddelingsnavn, jf. Innst. 360 S (2015-2016). Sammenslåing av fylker gjør det nødvendig å endre kommunenummer i det nye fylket, da de to første sifrene i et kommunenummer viser til fylke. Statistisk sentralbyrå (SSB) har foreslått nytt fylkesnummer for Trøndelag og nye kommunenummer for kommunene i Trøndelag som følge av fylkessammenslåingen. SSB ble bedt om å legge opp til en trygg og fremtidsrettet organisering av fylkesnummer og kommunenummer, samt å se hen til det pågående arbeidet med å legge til rette for om lag ti regioner. I dag ble det i statsråd fastsatt forskrift om nærmere regler ved sammenslåing av Nord- Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke. Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet fastsetter samtidig at Trøndelag fylke får fylkesnummer 50. Det er tidligere vedtatt sammenslåing av Rissa og Leksvik kommuner til Indre Fosen fra 1. januar 2018. Departementet fastsetter i tråd med forslag fra SSB at Indre Fosen får kommunenummer 5054. For de øvrige kommunene i nye Trøndelag fastslår departementet, i tråd med forslaget fra SSB, følgende nye kommunenummer: Postadresse Kontoradresse Telefon* Kommunalavdelingen Saksbehandler Postboks 8112 Dep Akersg. 59 22 24 90 90 Stein Ove Pettersen NO-0032 Oslo Org no. -

Slutrapporten

SLUTRAPPORT FÖR INTERREG-PROJEKTET "En Karolinerförening mot vision 2018" Projektnamn En karolinerförening mot vision 2018 Prioriterat område Attraktiv livsmiljö Huvudsaklig inriktning är För kultur och kreativitet insatser Svensk sökande/ Naboer AB 16 - 556503-2322 organisationsnr Norsk sökande/ Naboer AB 556503-2322 organisationsnr Projektledare Mattias Jaktlund, Naboer AB Kategori 58 Skydd och bevarande av kulturarvet Diarienummer N-30441-4-11 Sammanfattning Projektet "En Karolinerförening mot vision 2018" är ett tre-årigt INTERREG- projekt som påbörjades i juni 2011 och avslutades i augusti 2014. Huvudsyftet med projektet var att att starta upp en förening som kan agera huvudman för den kulturhistoriska som är kopplad till General Carl Gustav Armfeldts fälttåg mot Trondheim 1718-1719. Ett fälttåg som fick stora konsekvenser för de inblandade och som satt en stark prägel på människor i gränslandet mellan Jämtland och Tröndelag. Det har länge funnits ett inofficiellt nätverk med koppling till Armfeldts historia men eftersom man nu närmar sig 300-års markeringen av fälttåget och därmed ser för sig en rad aktiviteter kopplat till detta fanns ett behov av en stark, uttalad och enande huvudman. Därför önskade man starta en förening som skulle kunna ta detta huvudmannaskap. För att denna förening skulle få tänkt position var det viktigt att den fungerade gränsöverskridande och samlade de största aktörerna både i Sverige och i Norge. Den ”Jämt-Trönderska föreningen Armfeldts Karoliner” (JTAK) bildades i mars 2012 och är till både till sin konstruktion och sin sammansättning representerad i såväl Sverige som Norge. Föreningens stadgar är formulerade så att det tex alltid skall vara representanter från båda länderna i styrelsen. -

Nordic Cross-Border Statistics the Results of the Nordic Mobility Project 2016-2020

Nordic Cross-border Statistics The results of the Nordic Mobility project 2016-2020 1 Contents Foreword 4 Summary 6 Sammandrag 8 1. Background 10 2. Aim of the project 11 3. Need for cross-border statistics 12 3.1 A non-measured phenomenon 12 3.2 Under-coverage in national statistics 13 4. Preconditions for production of cross-border statistics 14 4.1 Legal preconditions for data exchange 14 4.2 Access to micro level (register) data 15 4.3 Statistical areas and variables 15 4.4 Technical preconditions for data exchange 16 5. Production process 17 5.1 Data exchange 17 5.2 Transfer of data 19 5.3 Combining data to matrices 20 5.4 Storage and/or deletion 20 6. Challenges 21 6.1 Legal challenge 21 6.2 Solution 22 7. Statistical findings 24 2 7.1 Education: definitions and data sources 24 7.2 Attendance in education 26 7.3 Highest education attained 33 7.4 Commuting 48 7.5 Migration 69 8. Results and achievements of the project 82 8.1 Publishing 82 8.2 Other results and consequences 84 9. Quality impact on national, Nordic and European statistics 85 9.1 Expectations of impact on quality in statistics 85 9.2 Code of Practice 85 9.3 Effects on the quality in national statistics 86 9.4 Effects on the quality in European statistics 89 9.5 Effects on the quality in Nordic cross-border statistics 90 10. Conclusions on the future of Nordic cross-border statistics 91 10.1 Interest on Nordic, national, regional – and European – level 91 10.2 Requirements for future production of Nordic cross-border statistics 91 10.3 Relevant cross-border statistics 92 Links 94 Annexes 96 About this publication 111 3 Foreword The Nordic Region aims to be the most sustainable and integrated region in the world by 2030. -

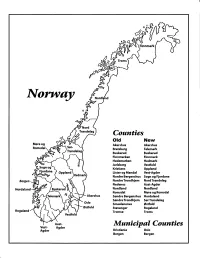

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Tydal, Selbu, Meråker, Frosta, Malvik Og Stjørdal

Forslag, 18. mars 2016 Intensjonsavtale for etablering av Værnes kommune for kommunene Tydal, Selbu, Meråker, Frosta, Malvik og Stjørdal Intensjonsavtalen bygger på «Grunnlagsdokumentet for en intensjonsavtale for etablering av VÆRNES kommune, 24. februar 2016» 1 1 Kommunene i Værnesregionen Stjørdal er vekstsenteret i regionen med sin sentrale beliggenhet i forhold til Trondheim, Værnes flyplass og kommunikasjonslinjene E-6, E-14 og jernbanen. Stjørdal vil være det naturlige sentrum i en ny Værnes kommune. Behovet for å sikre bærekraftig vekst er viktig for hele regionen og tilsier at det må fokuseres på vekst i tettstedene og i omlandet, i tillegg til i byen og kommunesenteret Stjørdal. Samlet befolkning i en ny kommune bestående av alle kommunene(6) i dagens Værnesregion var pr 31.12.15 på 47 165 innbyggere. Forslag til intensjonsavtale – Værnes kommune 2 2 Mål, avklaringer og hovedoppgaver for den nye kommunen 2.1 Generell målsetting Sammenslåingen skal gi en verdiskapende kommune som skal utnytte styrkene i de ulike tettstedene der alle jobber sammen for å utvikle attraktive og gode lokalsamfunn, med fremtidsrettede tjenester til det beste for den enkelte innbygger, hyttefolk, besøkende og næringsliv. 2.2 Avklaringer 2.2.1 Navnet på den nye kommunen Ettersom kommunene har jobbet meget godt sammen i Værnesregionen og lyktes med dette, er det naturlig å forslå at navnet Værnes videreføres i kommunenavnet. Værnesregionen er blitt kjent for sin evne til samarbeid og har høstet gode tilbakemeldinger både lokalt, regionalt og nasjonalt. Navnet Værnes, i kommunesammenheng, har allerede et godt omdømme som det bør bygges videre på. Av disse grunner er det naturlig å velge Værnes som navn på den nye kommunen. -

Bakgrunnsstatistikk

Bakgrunnsstatistikk Vedlegg til tilrådning kommunestruktur i Sør-Trøndelag 30.09.2016 Folk og samfunn Barnehage og Barn og foreldre Helse og omsorg Miljø og klima Landbruk, mat og Kommunal styring Plan og bygg Samfunnssikkerhet og opplæring reindrift beredskap Befolkningsutvikling 1992-2040 Osen 60 4 Roan 50 Åfjord 3 Befolkningsutvikling Bjugn i prosent 2016-2040 40 Frøya Ørland -9 - 0 % 2 Rissa 1 - 15 % Hitra 30 16 - 25 % Agdenes 1 26 - 50 % Snillfjord Trondheim 20 Malvik Hemne Orkdal Skaun 0 Klæbu 10 Melhus Selbu PROSENT (LINJE) PROSENT PROSENT (STOLPE) PROSENT -1 Meldal 0 Tydal Midtre Gauldal -2 Rennebu Holtålen -10 -3 -20 Oppdal Røros -30 -4 Befolkningsendring i prosent 1992-2016 Befolkningsframskriving i prosent 2016-2040 (MMMM-alternativet 2016) Befolkningsendring i prosent 2015-2016 BEFOLKNING Innbyggere Befolkningsfordeling < - 3.200 5 - 265 3.200 - 9.000 266 - 956 9.000 - 20.000 957 - 2340 20.000 - < 2341 - 5130 Kilde: SSB Dagens bo- og arbeidsmarked Kilde: NIBR 2013:1 Utvikling eldre fram til 2040 2016 2020 2040 2016-2040 Osen Prognose Personer 80 Personer 80 Personer 80 utvikling Roan Kommune år og eldre år og eldre år og eldre 2014 til 2040 Klæbu 137 168 448 227 % Malvik 379 453 1113 194 % Åfjord Prognose utvikling Skaun 264 273 639 142 % 2014 til 2040 Holtålen 107 135 240 124 % Bjugn Frøya 24 - 50 Trondheim 6552 6718 14635 123 % Ørland Orkdal 558 567 1213 117 % Rissa 51 - 80 Bjugn 247 272 521 111 % 81 - 100 Hitra Melhus 650 678 1360 109 % Agdenes 101 - 227 Oppdal 361 376 735 104 % Snillfjord Hitra 228 246 462 103 % Trondheim -

Regnskapsoversikter 3

Malvik kommune Regnskap 2012 REGNSKAPSOVERSIKTER 3 ØKONOMISK OVERSIKT – DRIFT 3 ØKONOMISK OVERSIKT – INVESTERING 4 HOVEDOVERSIKT – BALANSE 5 REGNSKAPSSKJEMA 1A – DRIFT 6 REGNSKAPSSKJEMA 1B – DRIFT 6 REGNSKAPSSKJEMA 2A – INVESTERING 7 REGNSKAPSSKJEMA 2B – INVESTERING 7 DRIFTSREGNSKAP 8 INVESTERINGSREGNSKAP 18 BALANSEREGNSKAP 22 1 Malvik kommune Regnskap 2012 NOTE NR. 1 ENDRING I ARBEIDSKAPITAL 27 DEL 1 ENDRING I ARBEIDSKAPITAL DRIFTSREGNSKAPET 27 DEL 2 ENDRING I ARBEIDSKAPITAL BALANSEN 27 NOTE NR. 2 GARANTIER GITT AV KOMMUNEN 28 DEL 1 GARANTIER 28 DEL 2 INNFRIELSER OG TAP 28 NOTE NR. 3 FORDRINGER OG GJELD TIL KOMMUNALE FORETAK OG INTERKOMMUNALT SAMARBEID. 29 NOTE NR. 4 FINANSIELLE ANLEGGSMIDLER 29 NOTE NR. 5 AVSETNINGER OG BRUK AV AVSETNINGER 30 DEL 1 ALLE FOND AVSETNINGER OG BRUK AV AVSETNINGER DRIFTS- OG INVESTERINGSREGNSKAPET 30 DEL 2 DISPOSISJONSFOND AVSETNINGER OG BRUK AV AVSETNINGER 30 DEL 3 BUNDET DRIFTSFOND AVSETNINGER OG BRUK AV AVSETNINGER 30 DEL 4 UBUNDET INVESTERINGSFOND AVSETNINGER OG BRUK AV AVSETNINGER 31 DEL 5 BUNDET INVESTERINGSFOND AVSETNINGER OG BRUK AV AVSETNINGER 31 NOTE NR. 6 KAPITALKONTO 32 NOTE NR. 7 SALG AV FINANSIELLE ANLEGGSMIDLER (FORSKRIFTSBESTEMT NOTE NR 8) 32 NOTE NR. 8 REGNSKAPSPRINSIPPER 33 NOTE NR. 9 ORGANISERING AV KOMMUNENS VIRKSOMHET (GKRS-BESTEMT NOTE NR 2) 34 NOTE NR. 10 PENSJONSFORPLIKTELSER (GKRS-BESTEMT NOTE NR 9) 38 NOTE NR. 11 VESENTLIGE TRANSAKSJONER (GKRS-BESTEMT NOTE NR 4) 40 NOTE NR. 12 ANLEGGSMIDLER 40 NOTE NR. 13 INVESTERINGER I NYBYGG OG NYANLEGG 42 NOTE NR. 14 GJELDSFORPLIKTELSER – TYPE GJELD OG FORDELING MELLOM LÅNGIVERE 43 NOTE NR. 15 AVDRAG PÅ GJELD 44 NOTE 16 SPESIFIKASJON OVER REGNSKAPSMESSIG MINDREFORBRUK (OVERSKUDD) DRIFT 45 NOTE 17 SPESIFIKASJON OVER REGNSKAPSMESSIG MERFORBRUK (UNDERSKUDD) INVESTERING 45 NOTE NR. -

Trondheim-Trøndelag Awarded 2022

THRIVING TOGETHER TOWARDS NEW HORIZONS EUROPEAN REGION OF GASTRONOMY TRONDHEIM - TRØNDELAG CANDIDATE 2022 Cover photo & photo on left: Jarle Hagen 3 | European Region of Gastronomy Candidate 2022 CONTENTS In The Heart of Norway | 8 Goals For Our Work As A European Region Of Gastronomy | 12 Prerequisite Of The Region | 17 Goal 1: Collaborate To Become A Leading International Food Region | 33 Goal 2: Known And Recognised As An International Food Destination | 41 Goal 3: Increase The Value Creation In Sustainable Food Production By Linking Knowledge Communities And Industries | 53 Goal 4: National Leaders In Recruitment To Food Production And Tourism | 57 Budget | 73 Ambassadors: Mikael Forselius and Astrid Aasen | 74-76 Commitment from Trondheim Municipality and Trøndelag Council Authority | 78-79 Photo: Jarle Hagen 5 | European Region of Gastronomy Candidate 2022 THRIVING TOGETHER TOWARDS NEW HORIZONS TRONDHEIM - TRØNDELAG Photo: Jarle Hagen 7 | European Region of Gastronomy Candidate 2022 Rørvik Røyrvik IN THE HEART OF NORWAY In the heart of Norway is the county of Trøndelag (Southern Sami: Trööndelage). Trondheim is Norway’s third largest city in terms Rissa of population. Trøndelag is Norway’s second largest county by land area and the fifth largest by population. The majority of the county’s more than 450,000 inhabitants live along the shores of the Trondheimsfjord, where much of the food production also occurs. Meråker MELHUS Trøndelag is an extremely diverse region. In contrast to other regions in Norway, the Trøndelag economy is largely based on food production and consequently has strong nature-based industries. We have seafood, meat, vegetables, drinks. Production and processing.