Simblist Dissertation Dec 2 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emily Jacir: Europa 30 Sep 2015 – 3 Jan 2016 Large Print Labels and Interpretation Galleries 1, 8 & 9

Emily Jacir: Europa 30 Sep 2015 – 3 Jan 2016 Large print labels and interpretation Galleries 1, 8 & 9 1 Gallery 1 Emily Jacir: Europa For nearly two decades Emily Jacir has built a captivating and complex artistic practice through installation, photography, sculpture, drawing and moving image. As poetic as it is political, her work investigates movement, exchange, transformation, resistance and silenced historical narratives. This exhibition focuses on Jacir’s work in Europe: Italy and the Mediterranean in particular. Jacir often unearths historic material through performative gestures and in-depth research. The projects in Europa also explore acts of translation, figuration and abstraction. (continues on next page) 2 At the heart of the exhibition is Material for a film (2004– ongoing), an installation centred around the story of Wael Zuaiter, a Palestinian intellectual who was assassinated outside his home in Rome by Israeli Mossad agents in 1972. Taking an unrealised proposal by Italian filmmakers Elio Petri and Ugo Pirro to create a fi lm about Zuaiter’s life as her starting point, the resulting installation contains documents, photographs, and sound elements, including Mahler’s 9th Symphony as one of the soundtracks to the work. linz diary (2003), is a performance by Jacir captured by one of the city’s live webcams that photographed the artist as she posed by a fountain in a public square in Linz, Austria, at 6pm everyday, over 26 days. During the performance Jacir would send the captured webcam photo of herself to her email list along with a small diary entry. In the series from Paris to Riyadh (drawings for my mother) (1998–2001), a collection of white vellum papers dotted with black ink are delicately placed side by side. -

Since 2017 Bezalel Academy for Art and Design, MFA

Hadas Maor Curiculum Vitae Professional Experience: Since 2017 Bezalel Academy for Art and Design, MFA Program, lecturer 2017 Bait LeOmanut Israelit, lecturer 2017 French Institute Focus Program 2016 Sculpture Quadrennial Riga 2016 Invited guest Lecture: Conservatism and Liberalism, appearances in contemporary culture 2015 Curator of the Israeli Pavilion, the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia 2014 Artist Mentor Artport, Tel Aviv 2012 The 2nd Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art Intellectual platform, invited guest Lecture: Contemplating the possibility of criticality within the field of visual art 2012 Lecturer of curatorial studies, School of Arts, Kibbutzim College of Education, Tel Aviv 2011 ARCOmadrid 2011, Professional Meetings, invited guest 2010 Professional visit to LA, organized by the LA-TLV partnership and The Jewish Federation of Los Angeles 2009 Study visit to Poland, organized by Adam Mickiewicz Institute, Warsaw 2007 Art Basel 2007, 7db platform for art professionals, invited guest Since 2006 Consultant to Bank Hapoalim Collection of Israeli Art 2006-2009 Consultant to the Angel Collection of Contemporary Art Since 2001 Curator of the Geny and Hanina Brandes Art Collection, Tel Aviv Since 1998 Independent contemporary art curator (The Tel Aviv Museum of Art, The Haifa Museum of Art, The Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, The Petach Tikva Museum of Art, The Ramat Gan Museum of Israeli Art, The Ein Harod Museum of Art, The Tel Aviv University Gallery and more) 1997 - 2005 Senior Lecturer -

Schechter@35: Living Judaism 4

“The critical approach, the honest and straightforward study, the intimate atmosphere... that is Schechter.” Itzik Biton “The defining experience is that of being in a place where pluralism “What did Schechter isn't talked about: it's lived.” give me? The ability Liti Golan to read the most beautiful book in the world... in a different way.” Yosef Peleg “The exposure to all kinds of people and a variety of Jewish sources allowed for personal growth and the desire to engage with ideas and people “As a daughter of immigrants different than me.” from Libya, earning this degree is Sigal Aloni a way to connect to the Jewish values that guided my parents, which I am obliged to pass on to my children and grandchildren.” Schechter@35: Tikva Guetta Living Judaism “I acquired Annual Report 2018-2019 a significant and deep foundation in Halakhah and Midrash thanks to the best teachers in the field.” Raanan Malek “When it came to Jewish subjects, I felt like an alien, lost in a foreign city. At Schechter, I fell into a nurturing hothouse, leaving the barren behind, blossoming anew.” Dana Stavi The Schechter Institutes, Inc. • The Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, the largest M.A. program in is a not for profit 501(c)(3) Jewish Studies in Israel with 400 students and 1756 graduates. organization dedicated to the • The Schechter Rabbinical Seminary is the international rabbinical school advancement of pluralistic of Masorti Judaism, serving Israel, Europe and the Americas. Jewish education. The Schechter Institutes, Inc. provides support • The TALI Education Fund offers a pluralistic Jewish studies program to to four non-profit organizations 65,000 children in over 300 Israeli secular public schools and kindergartens. -

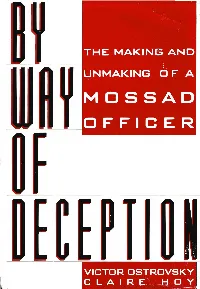

Het Web Van De Mossad Gratis Epub, Ebook

HET WEB VAN DE MOSSAD GRATIS Auteur: Claire Hoy Aantal pagina's: 366 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9789065904799 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Het web van de Mossad : onthullingen van een Israelisch geheim agent – Claire Hoy, Victor Ostrovsky Onthullingen van een Israëlisch geheim agent. Boeken van en over Britse spionnen krijgen we de laatste tijd in voldoende mate voorgeschoteld, maar onthullingen van een gewezen Israëlisch geheim agent zijn relatief nieuw. Vermakelijk zijn de anekdoten die hij weet aan te halen over hun tests in de jaren durende opleiding en sensationeel zijn de verhalen over de geplande aanslag op Golda Meir en het relaas van de terrorist Carlos. Het boek wordt besloten met interessante bijlagen over de struktuur en de werkwijze van de Mossad. Dit is een werk dat zeker zijn plaats verdient in de snel ruimer wordende bibliotheek van en over spionnen. Zwart omslag net zoals de recent verschenen boeken over Blake en Philby , zilveren, blauwe en witte belettering. Primary Menu. Zoeken naar:. Conditie: In redelijke staat, gebruikerssporen. Categorie: Israël. Beschrijving Extra informatie Beschrijving Onthullingen van een Israëlisch geheim agent Boeken van en over Britse spionnen krijgen we de laatste tijd in voldoende mate voorgeschoteld, maar onthullingen van een gewezen Israëlisch geheim agent zijn relatief nieuw. Biblion recensie, Chris Vandenbroucke. Extra informatie Gewicht g Afmetingen × × 30 mm. _Soortgelijke boeken Geven twee brandende olietankers de aanzet tot een regiowijde oorlog rond de Perzische Golf? De VS wezen alvast beschuldigend naar Iran. Voormalige officieren van de Mossad, privédetectives en valse getuigen: Harvey Weinstein zette de grote middelen in om actrice Rose McGowan en journalisten het zwijgen op te leggen. -

Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS)

P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies (JCSS) The purpose of the Jaffee Center is, first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel's national security as well as Middle East regional and international secu- rity affairs. The Center also aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are - or should be - at the top of Israel's national security agenda. The Jaffee Center seeks to address the strategic community in Israel and abroad, Israeli policymakers and opinion-makers and the general public. The Center relates to the concept of strategy in its broadest meaning, namely the complex of processes involved in the identification, mobili- zation and application of resources in peace and war, in order to solidify and strengthen national and international security. To Jasjit Singh with affection and gratitude P. R. Kumaraswamy Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations Memorandum no. 55, March 2000 Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies 6 P. R. Kumaraswamy Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv, 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel Tel. 972 3 640-9926 Fax 972 3 642-2404 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.tau.ac.il/jcss/ ISBN: 965-459-041-7 © 2000 All rights reserved Graphic Design: Michal Semo Printed by: Kedem Ltd., Tel Aviv Beyond the Veil: Israel-Pakistan Relations 7 Contents Introduction .......................................................................................9 -

Destination: Jerusalem Servees

Destination: Emily Jacir’s audio work Untitled (servees) was produced as a site specific work and Jerusalem Servees installed in 2008 at Damascus Gate, in Jerusalem’s Old City. It was displayed as Interview with part of the second edition of the Jerusalem Emily Jacir Show organized by The Ma’mal Foundation. In its form, content and location, it was a Adila Laidi-Hanieh crucible of contemporary Palestinian visual art and culture, of Jacir’s practice, and of Palestinian efforts to affirm presence and ownership of the city in the face of the forced ‘silent transfer’. Emily Jacir is one of the most successful Palestinian contemporary artists and one of the best known internationally, as well as arguably its most recognized. She won numerous prestigious awards including the 2008 Hugo Boss Prize of the Guggenheim Foundation in New York; where the Jury noted her, “rigorous conceptual practice… bears witness to a culture torn by war Photo courtesy Emily Jacir. and displacement through projects that © Emily Jacir 2009 unearth individual narratives and collective Jerusalem Quarterly 40 [ 59 ] experiences”. In 2007 she won the Prince Claus Award, an annual prize from the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development in the Hague, which described Jacir as, “an exceptionally talented artist whose works seriously engages the implications of conflict” (PCF). In 2007, she won the ‘Leone d’Oro a un artista under 40’ - (Golden Lion Award for an artist under 40), at the Venice Biennale, the oldest and premier international art event in Europe, often dubbed ‘the Olympics of art’, for “a practice that takes as its subject exile in general and the Palestinian issue in particular, without recourse to exoticism”. -

Remote Control: Distance in Two Works by Emily Jacir and Wafaa Bilal

Remote Control: Distance in Two Works by Emily Jacir and Wafaa Bilal Kerr Houston s a part of her 2001-3 project Where We Come honor of all those who gave their lives for Palestine.” To From, the Palestinian-American artist Emily Jacir the right, the beach appeared, in early morning blues, on Aasked dozens of Palestinian exiles and children a small video screen. of Palestinian refugees a simple question: “If I could do Four years later, in May and June of 2007, the anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it Iraqi-American artist Wafaa Bilal took up residence be?” Able to travel relatively freely within Israel due to in a Chicago art gallery, in a project called Domestic her American passport, Jacir then executed the wishes Tension. Subsisting on donated food and drink, Bilal of several respondents, recording her performances in lived for thirty days in a simulated bedroom/office space photographs and videos, which she exhibited alongside that was enclosed in transparent walls. Visible to gallery transcriptions of the requests and brief personal histories visitors, the space was also outfitted with computers of the exiles (Figure 1). “Drink the water,” ran one and a streaming webcam, and visitors to Bilal’s website appeal, put forward by a woman named Omayma, “in could control the camera and periodically interact with my parents’ village” – and, adjacent, viewers saw an him through an online chatroom or view videos that he image of a glassful of water, tilted towards the camera. posted on Youtube. Or they could attempt to shoot him, “Go to Haifa’s beach at the moment of the first light,” read another request, made by a man named Mohannad, Figure 1. -

By Way of Deception,” Has Been Produced by Lovers of Freedom

THE MAKING AND IUNMAKING O F A IMOSSAD VICTOR OSTROVSKY C LA I R EL--- -- HOY- This electronic version of “By Way of Deception,” has been produced by lovers of freedom. It has been produced with the understanding that the Israeli Mossad operates within an international Jewish conspiracy (belief in a Jewish Conspiracy does not make one a Nazi, member of the KKK, or Islamist, nor does it make one a hate mongerer) which it aids tremendously. Victor Ostrovsky may or may not be telling all of the truth and the information contained in this book may have been created so as to mislead about the real workings of the Mossad but nonetheless, we feel it contains enough credible information that makes it worth while to read. This book has been provided to you for free via the internet and all that we ask is that you open your mind and educate yourself at the following web sites: www.libertyforum.org www.iamthewitness.com www.prothink.org www.samliquidation.com/lordjesus.htm www.conspiracyworld.com www.judicial-inc.biz www.rense.com www.realjewnews.com By Way of Deception Victor Ostrovsky and Claire Hoy St. Martin’s Press New York ISBN 0-312-05613-3 Contents AUTHOR’S FORWARD vii PROLOGUE: OPERATION SPHINX 1 PART I CADET 16 1 Recruitment 31 2 School Days 51 3 Freshmen 66 4 Sophomores 84 5 Rookies 99 PART II INSIDE AND OUT 6 The Belgian Table 117 7 Hairpiece 137 8 Hail and Farewell 153 PART III BY WAY OF DECEPTION 9 Strella 177 10 Carlos 197 11 Exocet 217 12 Checkmate 230 13 Helping Arafat 246 14 Only in America 267 15 Operation Moses 287 16 Harbor Insurance 302 17 Beirut 310 EPILOGUE 332 ----------------------------------------------------- APPENDICES 337 GLOSSARY of TERMS 357 INDEX 362 BY WAY OF DECEPTION ix names and be open himself, made it much easier over time to conclude that he is the genuine article: a former Mossad katsa. -

Israeli) Star of Hope Agamograph 29 X 31 Cm (11 X 12 In.) Signed Lower Right, Numbered '8/25' Lower Left

1* Yaacov Agam b.1928 (Israeli) Star of Hope agamograph 29 x 31 cm (11 x 12 in.) signed lower right, numbered '8/25' lower left $1,500-1,800 2* Yaacov Agam b.1928 (Israeli) Untitled color silkscreen mounted on panel 57 x 62 cm (22 x 24 in.) signed lower right, numbered 'L/CXLIV' lower left $400-500 3 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Sheep head acrylic on canvas 30 x 30 cm (12 x 12 in.) signed lower left and again on the reverse $450-550 4 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Motherland charcoal on paper 27 x 35 cm (11 x 14 in.) signed lower right $150-220 5 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Valley of sadness pencil on paper 27 x 35 cm (11 x 14 in.) signed lower right $100-150 6* Ruth Schloss 1922-2013 (Israeli) 1 Girl in red dress, 1965 oil on canvas 74 x 50 cm (29 x 20 in.) signed lower right Provenance: Private collection, USA. $3,500-4,000 7 Sami Briss b.1930 (Israeli, French) Doves oil on wood 8 x 10 cm (3 x 4 in.) signed lower center $500-650 8 Nahum Gilboa b.1917 (Israeli) Rural landscape with wooden bridge mixed media on canvasboard 23 x 30 cm (9 x 12 in.) signed lower right, signed and titled on the reverse $1,800-2,200 9 Audrey Bergner b.1927 (Israeli) Flutist oil on canvas 40 x 30 cm (16 x 12 in.) signed lower right, signed and titled on the reverse $4,800-5,500 10 Yohanan Simon 1905-1976 (Israeli) Vegetarian Evolution, 1971 oil on canvas 46 x 54 cm (18 x 21 in.) signed in English lower left, signed in Hebrew and dated lower right, signed, dated and titled on the stretcher $8,000-10,000 11* Yohanan Simon 1905-1976 (Israeli) Wedding, 1969 2 oil on canvas 15 x 23 cm (6 x 9 in.) signed in English lower left and in Hebrew lower right $2,200-2,500 12 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Fallow deer iron cut-out 34 x 30 x 2 cm (13 x 12 x 1 in.) initialled $1,400-1,600 13 Naftali Bezem b. -

Art As a Powerful Tool for Knowledge

NESRINE REZEK Art as a Powerful Tool for Knowledge Most of us believe in the power of art, how story can change one’s life, with stories we can connect with other, we reach others who we may never meet, words gathering to form sentences, to fabric stories, to form our history our culture our identity and our future, simply our life is a story. It’s our way to share our experience with others, the ability to express our interests, to discuss our goals, and to reach positive change. From here Emily Jacir began her fight and journey to tell her story or our story, to uncover facts and to convey the truth to the world. Emily Jacir “is Palestinian artist and filmmaker. Born in Bethlehem in 1970, Jacir attended the University of Dallas, Irving, the Memphis College of Art and the Whitney Independent Study Program and has been living and working between New York and the West Bank. It may be argued one of the main Palestinian artists working today, she has received a number of prominent awards. Jacir utilizes different kinds of media such as video, film, installation, sound, photography, performance, and writing in her work and has shown widely throughout Europe, United States and the Middle East since 1994.”1 Her style was different, through her artistic work, Jacir gives the narrative right to the Palestinian, and re-focuses on the details of the Palestinian life before Nakba. She shows how pictures as one form of narrativity through narratological concepts is a powerful tool to reproduce meanings, in order to represent and retrieve history. -

Global Conference for Jewish Museums

UPHEAVAL GLOBAL CONFERENCE FOR JEWISH MUSEUMS COUNCIL OF AMERICAN JEWISH MUSEUMS ASSOCIATION OF EUROPEAN JEWISH MUSEUMS APRIL 2021 Throughout the past year of the pandemic, Jewish museums have faced unprecedented challenges and have responded. They have worked together in new configurations, have been resources for new communities, and are envisioning new ways to be museums for the present and the future. The Council of American Jewish Museums is proud to present its first online, global conference for Jewish museums—developed in partnership with the Association of European Jewish Museums. This year, we are collectively unpacking the topic of Upheaval—recognizing that our profession has been greatly impacted by pressing issues and the crises of our times. At the same time, however, museums are creating their own upheavals—through innovation, reconfiguration, and approaches that will reshape our work for years to come. GLOBAL CONFERENCE FOR JEWISH MUSEUMS | APRIL 2021 2 PROGRAM TUESDAYUPHEAVAL APRIL 20 11:00 AM EDT WELCOME 11:10 AM EDT JEWISH MUSEUMS: CONTEXT MATTERS For this year’s program we have come together as a global community: to address common challenges and opportunities, to build a collegial community, and to articulate implications for the worldwide field of Jewish museums. While Jewish museums around the world share many mutual concerns, each one operates within its own geographic, political, and social realities. This session explores, from various angles, how context profoundly shapes the work of Jewish museums—from Tel Aviv and Sydney, to Hohenems and Washington, DC. Speakers AVRIL ALBA Consulting Scholar, Holocaust Memorial Museum–Sydney Jewish Museum KARA BLOND Executive Director, Capital Jewish Museum HANNO LOEWY Director, Jewish Museum Hohenems DAN TADMOR CEO, ANU—Museum of the Jewish People Moderated by BARBARA KIRSHENBLATT-GIMBLETT Ronald S. -

Sigalit Landau

Sigalit Landau Born in Jerusalem 1969, lives and works in Tel Aviv Biography: Sigalit Landau, an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, video, painting, photography, and sculpture. She graduated from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem in 1994. Landau’s work has been exhibited in leading venues around the world. Her one-person shows include: Temple Mount, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem (1995); VoorWerk 5, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam (1996); Resident Alien I, Documenta X, Kassel (1997); The Country, Alon Segev Gallery, Tel Aviv (2002); Carcel de Amor, Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid (2005); Bauchaus 04 (performance), The Armory Show, New York City (2005); The Endless Solution, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv (2005); The Dining Hall, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2007); Projects 87: Sigalit Landau, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City (2008); Salt Sails + Sugar Knots, Kamel Mennour Gallery, Paris (2008); One Man’s Floor Is Another Man’s Feelings, The Israeli Pavilion, 54th International Art Exhibition—la Biennale di Venezia (2011); Caryatid, The Negev Museum of Art, Beersheba (2012); Infinite Games, Solyanka State Gallery, Moscow (2012); Margin, Műcsarnok Kunsthalle, Budapest (2013); The Ram in the Thicket, Ginza Maison Hermès, Tokyo (2013); Phoenician Sand Dance, MACBA, Barcelona (2014); Moving to Stand Still, Koffler Centre of Fine Arts, Toronto (2014); Better Place, cellule516, Marseille (2015); The Experience of Auschwitz, MOCAK, Krakow (2015); Shelter, Place des Arts, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Montreal (2015); Miqlat, Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, Paris (2016); Sorrow Grove, Wiener Festwochen, Vienna (2016); Growth and Change: Sigalit Landau, Jewish Federation, Cleveland, Ohio (2019); Sea Stains, Mishkenot Sha’ananim, Jerusalem (2019); Salt Years, Museum der Moderne Salzburg (2019).