Strengthening Canadian Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journaux Journals

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 37th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 37e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 12 No 12 Tuesday, February 13, 2001 Le mardi 13 février 2001 10:00 a.m. 10 heures The Clerk informed the House of the unavoidable absence of the Le Greffier informe la Chambre de l’absence inévitable du Speaker. Président. Whereupon, Mr. Kilger (Stormont — Dundas — Charlotten- Sur ce, M. Kilger (Stormont — Dundas — Charlottenburgh), burgh), Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees of the Vice–président et président des Comités pléniers, assume la Whole, took the Chair, pursuant to subsection 43(1) of the présidence, conformément au paragraphe 43(1) de la Loi sur le Parliament of Canada Act. Parlement du Canada. PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES PRESENTING REPORTS FROM COMMITTEES PRÉSENTATION DE RAPPORTS DE COMITÉS Mr. Lee (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the M. Lee (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Government in the House of Commons), from the Standing Chambre des communes), du Comité permanent de la procédure et Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, presented the des affaires de la Chambre, présente le 1er rapport de ce Comité, 1st Report of the Committee, which was as follows: dont voici le texte : The Committee recommends, pursuant to Standing Orders 104 Votre Comité recommande, conformément au mandat que lui and 114, that the list of members and associate members for confèrent les articles 104 et 114 du Règlement, que la liste -

Fall 2017 Volume 30 Issue 3

Fall 2017 Volume 30 Issue 3 Happy Holidays Heritage Mississauga’s Newsletter Contributors in this issue Inside . President’s Message / 3 The Editor’s Desk / 4 Vimy Park /4 CF-100 Canuck / 5 What Did You Bring? / 6 Don Marjorie Greg Thompson’s Company / 7 Jayme Meghan Barbara Hancock Hancock Carraro Haunted Mississauga / 7 Gaspar Mackintosh O’Neil Programs Plus / 8 the Credits / 9 Staff Contacts The Pines / 10 Jayme Gaspar: x 31 [email protected] Centennial Torch / 11 Meghan Mackintosh: x 23 [email protected] Confederation Caravan / 11 Jenny Walker: x 22 [email protected] Queen of the Township / 12 Kelly Ralston: x 0 [email protected] W. P. Howland / 13 Matthew Wilkinson: x 29 [email protected] Centennial Flag / 14 Kelly Jenny Remembering Dieppe / 14 Ralston Walker Heritage Matters / 16 NEXT DEADLINE January 19, 2018 Watch our Editor: latest video! Jayme Gaspar, Executive Director Content “This is Dundas Street” can be found on our Meghan Mackintosh, Outreach Matthew Linda YouTube channel: Coordinator, Matthew Wilkinson, Wilkinson Yao Historian www.YouTube.com/HeritageMississauga Layout & Typesetting Jayme Gaspar HERITAGE NEWS is a publication of the Mississauga Heritage Foundation Inc. The Foundation Photography (est. 1960) is a not-for-profit organization which identifies, researches, interprets, promotes, and Ancesty.ca, Councillor Carolyn encourages awareness of the diverse heritage resources relating to the city of Mississauga. The Parrish, Hancock Family, Heritage -

Council Minutes – April 8, 2009

MINUTES SESSION 7 THE COUNCIL OF THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF MISSISSAUGA (www.mississauga.ca ) WEDNESDAY, APRIL 8, 2009, 9:00 A. M. COUNCIL CHAMBER 300 CITY CENTRE DRIVE MISSISSAUGA, ONTARIO L5B 3C1 INDEX 1. CALL TO ORDER 1 2. DISCLOSURES OF PECUNIARY INTEREST 1 3. MINUTES OF PREVIOUS COUNCIL MEETINGS 1 4. APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA 2 5. PRESENTATIONS 2 6. DEPUTATIONS 6 7. PUBLIC QUESTION PERIOD 12 8. CORPORATE REPORTS 13 9. COMMITTEE REPORTS 18 10. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 49 11. PETITIONS 51 12. CORRESPONDENCE 51 13. RESOLUTIONS 61 14. BY-LAWS 71 15. OTHER BUSINESS 75 16. INQUIRIES 75 17. NOTICES OF MOTION 76 18. CLOSED SESSION 78 19. CONFIRMATORY BY-LAW 79 20. ADJOURNMENT 79 Council - 1 - April 8 2009 PRESENT: Mayor Hazel McCallion Councillor Carmen Corbasson Ward 1 Councillor Pat Mullin Ward 2 Councillor Maja Prentice Ward 3 Councillor Frank Dale Ward 4 Councillor Eve Adams Ward 5 Councillor Carolyn Parrish Ward 6 Councillor Katie Mahoney Ward 8 Councillor Sue McFadden Ward 10 Councillor George Carlson Ward 11 ABSENT: Councillor Nando Iannicca Ward 7 Councillor Pat Saito Ward 9 STAFF: Janice Baker, City Manager and Chief Administrative Officer Martin Powell, Commissioner of Transportation and Works Brenda Breault, Commissioner of Corporate Services and Treasurer Paul Mitcham, Commissioner of Community Services Ed Sajecki, Commissioner of Planning and Building Mary Ellen Bench, City Solicitor Crystal Greer, City Clerk Shalini Alleluia, Legislative Coordinator Evelyn Eichenbaum, Legislative Coordinator 1. CALL TO ORDER The meeting was called to order at 9:10 a.m. by Mayor Hazel McCallion, with the saying of the Lord’s Prayer. -

The Canadian "Garrison Mentality" and Anti-Americanism at The

STUDIES IN DEFENCE & FOREIGN POLICYNumber 4 / May 2005 The Canadian “Garrison Mentality” and Anti-Americanism at the CBC Lydia Miljan and Barry Cooper Calgary Policy Research Centre, The Fraser Institute Contents Executive summary . A Garrison Mentality . 3 Anti-American Sentiment at “The National” . 8 References . 7 About the Authors & Acknowledgments . 9 A FRASER INSTITUTE OCCASIONAL PAPER Studies in Defence and Foreign Policy are published periodically throughout the year by The Fraser Institute. The Fraser Institute is an independent Canadian economic and social research and educational organization. It has as its objective the redirection of public attention to the role of competitive markets in providing for the well-being of Canadians. Where markets work, the Institute’s interest lies in trying to discover prospects for improvement. Where markets do not work, its interest lies in finding the reasons. Where competitive markets have been replaced by government control, the interest of the Institute lies in documenting objectively the nature of the improvement or deterioration resulting from government intervention. The work of the Institute is assisted by an Editorial Advisory Board of internationally renowned economists. The Institute enjoys registered charitable status in both Canada and the United States and is funded entirely by the tax-deductible contributions of its supporters, sales of its publications, and revenue from events. To order additional copies of Studies in Defence and Foreign Policy, any of our other publications, or a catalogue of the Institute’s publications, please contact the publications coordinator via our toll-free order line: .800.665.3558, ext. 580; via telephone: 604.688.022, ext. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

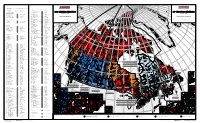

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

Wednesday, April 24, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 032 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, April 24, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1883 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, April 24, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [English] _______________ LIBERAL PARTY OF CANADA Prayers Mr. Ken Epp (Elk Island, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, voters need accurate information to make wise decisions at election time. With _______________ one vote they are asked to choose their member of Parliament, select the government for the term, indirectly choose the Prime The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now Minister and give their approval to a complete all or nothing list of sing O Canada, which will be led by the hon. member for agenda items. Vancouver East. During an election campaign it is not acceptable to say that the [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] GST will be axed with pledges to resign if it is not, to write in small print that it will be harmonized, but to keep it and hide it once the _____________________________________________ election has been won. It is not acceptable to promise more free votes if all this means is that the status quo of free votes on private members’ bills will be maintained. It is not acceptable to say that STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS MPs will be given more authority to represent their constituents if it means nothing and that MPs will still be whipped into submis- [English] sion by threats and actions of expulsion. -

Wednesday, May 8, 1996

CANADA VOLUME 134 S NUMBER 042 S 2nd SESSION S 35th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, May 8, 1996 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) OFFICIAL REPORT At page 2437 of Hansard Tuesday, May 7, 1996, under the heading ``Report of Auditor General'', the last paragraph should have started with Hon. Jane Stewart (Minister of National Revenue, Lib.): The House of Commons Debates are also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 2471 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, May 8, 1996 The House met at 2 p.m. [Translation] _______________ COAST GUARD Prayers Mrs. Christiane Gagnon (Québec, BQ): Mr. Speaker, another _______________ voice has been added to the general vehement objections to the Coast Guard fees the government is preparing to ram through. The Acting Speaker (Mr. Kilger): As is our practice on Wednesdays, we will now sing O Canada, which will be led by the The Quebec urban community, which is directly affected, on hon. member for for Victoria—Haliburton. April 23 unanimously adopted a resolution demanding that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans reverse its decision and carry [Editor’s Note: Whereupon members sang the national anthem.] out an in depth assessment of the economic impact of the various _____________________________________________ options. I am asking the government to halt this direct assault against the STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Quebec economy. I am asking the government to listen to the taxpayers, the municipal authorities and the economic stakehold- [English] ers. Perhaps an equitable solution can then be found. -

The Evolution of Canadian and Global

Carleton University The Review of Bill C-91: Pharmaceutical Policy Development under a Majority Liberal Government A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Institute of Political Economy by Jason Wenczler, M.Sc. Ottawa, Canada September 2009 ©2009, Jason Wenczler Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-60270-6 Our file Notre r6f§rence ISBN: 978-0-494-60270-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Over 40% of Canadian Teens Think America Is "Evil" by Arthur Weinreb, Associate Editor, Canada Free Press

| Email A Friend | Subscribe To Canadafreepress | Email Canadafreepress.com | Canadafreepress.com -- Politically Incorrect Poll: over 40% of Canadian teens think America is "evil" by Arthur Weinreb, Associate Editor, Canada Free Press June 30, 2004 Can West News Services, owners of several Canadian newspapers including the National Post as well as the Global Television Network commissioned a series of polls to determine how young people feel about the issues that were facing the country’s voters. Dubbed "Youth Vote 2004", the polls, sponsored by the Dominion Institute and Navigator Ltd. were taken with a view to getting more young people involved in the political process. In one telephone poll of teens between the ages of 14 and 18, over 40 per cent of the respondents described the United States as being "evil". That number rose to 64 per cent for French Canadian youth. This being Canada, the amount of anti-Americanism that was found is not surprising. What is significant is the high number of teens who used the word "evil" to describe our southern neighbour. As Misty Harris pointed out in her column in the Saskatoon Star Phoenix, evil is usually associated with serial killers and "kids who tear the legs off baby spiders." These teens appear to equate George W. Bush and Americans with Osama bin Laden and Hitler, although it is unknown if the teens polled would describe the latter two as being evil. Whether someone who orders planes to be flown into heavily populated buildings would fit that description would make a good subject for a future poll. -

Council Minutes – October 22, 2008

MINUTES SESSION 18 THE COUNCIL OF THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF MISSISSAUGA (www.mississauga.ca ) WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 22, 2008, 9:00 A. M. COUNCIL CHAMBER 300 CITY CENTRE DRIVE MISSISSAUGA, ONTARIO L5B 3C1 INDEX 1. CALL TO ORDER 1 2. DISCLOSURES OF PECUNIARY INTEREST 1 3. MINUTES OF PREVIOUS COUNCIL MEETINGS 1 4. APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA 2 5. PRESENTATIONS 2 6. DEPUTATIONS 3 7. PUBLIC QUESTION PERIOD 10 8. CORPORATE REPORTS 11 9. COMMITTEE REPORTS 13 10. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 25 11. PETITIONS 25 12. CORRESPONDENCE 25 13. RESOLUTIONS 28 14. BY-LAWS 34 15. OTHER BUSINESS 37 16. INQUIRIES 38 17. NOTICES OF MOTION 40 18. CLOSED SESSION 40 19. MATTERS ARISING OUT OF CLOSED SESSION 44 20. CONFIRMATORY BY-LAW 44 20. ADJOURNMENT 44 Council - 1 - October 22, 2008 PRESENT: Mayor Hazel McCallion Councillor Carmen Corbasson Ward 1 Councillor Pat Mullin Ward 2 Councillor Maja Prentice Ward 3 Councillor Frank Dale Ward 4 Councillor Eve Adams Ward 5 Councillor Carolyn Parrish Ward 6 Councillor Nando Iannicca Ward 7 Councillor Katie Mahoney Ward 8 Councillor Pat Saito Ward 9 Councillor George Carlson Ward 11 ABSENT: Councillor Sue McFadden Ward 10 STAFF: Janice Baker, City Manager and Chief Administrative Officer Brenda Breault, Commissioner of Corporate Services and Treasurer Paul Mitcham, Commissioner of Community Services Martin Powell, Commissioner of Transportation and Works Ed Sajecki, Commissioner of Planning and Building Mary Ellen Bench, City Solicitor Crystal Greer, City Clerk Shalini Alleluia, Legislative Coordinator Kevin Arjoon, Legislative Coordinator 1. CALL TO ORDER The meeting was called to order at 9:15 a.m. -

Perceptions of War

PERCEPTIONS OF WAR By CHRISTINE OLDFIELD B.A., University of Alberta, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In HUMAN SECURITY AND PEACEBUILDING We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard. ______ Susan Brown Academic Supervisor ______ Alejandro Palacios Academic Lead, MA Human Security and Peacebuilding ______ Dr. Gregory Cran, Director School of Conflict and Peace Management ROYAL ROADS UNIVERSITY November 2008 © Christine Oldfield, 2008 ISBN:978-0-494-50421-5 Perceptions of War 2 Abstract The objective of this research is to examine governmental messaging during times of international conflict, specifically Canada’s mission in Afghanistan, as it relates to public perception. This paper will test the effectiveness of government messaging during a specific time of high-risk international deployment. The first section is a quantitative analysis from the various forms of public feedback. In order to measure the public’s responses to messaging, comparisons of the responses before and after the government’s release of a message have been evaluated. The second section comprises of a qualitative analysis to determine the correlation, if any, between the results from the public feedback and the government messaging. It is hoped that the findings of this research will contribute to an understanding of how messaging can be used to influence the public’s views and confidence, particularly if is related to a high risk and possibly unpopular activity. Perceptions