Life in Teangue from 'Private Donald Campbell 92Nd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Painting Time: the Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay

SCOTTISH ARCHIVES 2013 Volume 19 © The Scottish Records Association Painting Time: The Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay Anne MacLeod This article examines sketches and drawings of the Highlands by John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85), who is now largely remembered for his contribution to folklore studies in the north-west of Scotland. An industrious polymath, with interests in archaeology, ethnology and geological science, Campbell was also widely travelled. His travels in Scotland and throughout the world were recorded in a series of journals, meticulously assembled over several decades. Crammed with cuttings, sketches, watercolours and photographs, the visual element within these volumes deserves to be more widely known. Campbell’s drawing skills were frequently deployed as an aide-memoire or functional tool, designed to document his scientific observations. At the same time, we can find within the journals many pioneering and visually appealing depictions of upland and moorland scenery. A tension between documenting and illuminating the hidden beauty of the world lay at the heart of Victorian aesthetics, something the work of this gentleman amateur illustrates to the full. Illustrated travel diaries are one of the hidden treasures of family archives and manuscript collections. They come in many shapes and forms: legible and illegible, threadbare and richly bound, often illustrated with cribbed engravings, hasty sketches or careful watercolours. Some mirror their published cousins in style and layout, and were perhaps intended for the print market; others remain no more than private or family mementoes. This paper will examine the manuscript journals of one Victorian scholar, John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85). -

![Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1473/inverness-county-directory-for-1887-1920-541473.webp)

Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]

INVERNE COUNTY DIRECTORY 899 PRICE ONE SHII.I-ING. COAL. A" I i H .J.A 2 Lomhara ^ai-eei. UNlfERNESS ^^OCKB XSEND \V It 'lout ^'OAL produced .^mmmmmmmm ESTABLISHED 1852. THE LANCASHIRE INSUBANCE COY. (FIRE, IIFE, AND EMPLOYERS' LIABILITY). 0£itpi±a.l, THf-eo IVIiliion® Sterling: Chief Offices EXCHANGE STREET, MANCHESTER Branch Office in Inverness— LANCASHIRE INSURANCE BUILDINGS, QUEEN'S GATE. SCOTTISH BOARD- SiR Donald Matheson, K.C.B., Cliairinan, Hugh Brown, Esq. W. H. KiDBTON, Esq. David S. argfll, Esq. Sir J. King of ampsie, Bart., LL.D. Sir H arles Dalrymple, of Newhailes, Andrew Mackenzie, Esq. of Dahnore. Bart., M.P. Sir Kenneth J. Matheson of Loclialsh, Walter Duncan, Esq, Bart. Alexander Fraser, Esq., InA^eriiess. Alexander Ross, Esq., LL.D., Inverness. Sir George Macpherson-Gr-nt, Bart. Sir James A. Russell, LL.D., Edin- (London Board). burgh. James Keyden, Esq. Alexander Scott, Esq., J. P., Dundee- Gl(is(f<nv Office— Edinhuvfih Office— 133 West Georf/e Street, 12 Torh JiiMilings— WM. C. BANKIN, Re.s. Secy. G. SMEA TON GOOLD, JRes. Secy. FIRE DEPARTMENT Tlie progress made in the Fire Department of the Company has been very marked, and is the result of the promptitude Avith which Claims for loss or damage by Fiie have always been met. The utmost Security is afforded to Insurers by the amjjle apilal and large Reserve Fund, in addition to the annual Income from Premiums. Insurances are granted at M> derate Rates upon almost every description of Property. Seven Years' Policies are issued at a charge for Six Years only. -

Braunholtz-Speight, Timothy Herford

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Power and community in Scottish community land initiatives Braunholtz-Speight, Timothy Herford DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Power and community in Scottish community land initiatives A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Aberdeen Tim Braunholtz-Speight BA (Hons) University of Leeds MA University of Leeds 2014 1 Declaration I confirm that this thesis has been entirely composed by me, the candidate, and is my work. -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

Migration of Swallows

Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (I978) vol 6o HUNTERIANA John Hunter, Gilbert White, and the migration of swallows I F Lyle, ALA Library of the Royal College of Surgeons of England Introduction fied than himself, although he frequently sug- gested points that would be worthy of investi- This year is not only the 25oth anniversary of gation by others. Hunter, by comparison, was John Hunter's birth, but it is also I90 years the complete professional and his work as a since the publication of Gilbert White's Nat- comparative anatomist was complemented by ural History and Antiquities of Selborne in White's fieldwork. The only occasion on which December I788. White and Hunter were con- they are known to have co-operated was in temporaries, White being the older man by I768, when White, through an intermediary, eight years, and both died in I 793. Despite asked Hunter to undertake the dissection of a their widely differing backgrounds and person- buck's head to discover the true function of the alities they had two very particular things in suborbital glands in deer3. Nevertheless, common. One was their interest in natural there were several subjects in natural history history, which both had entertained from child- that interested both of them, and one of these hood and in which they were both self-taught. was the age-old question: What happens to In later life both men referred to this. Hunter swallows in winter? wrote: 'When I was a boy, I wanted to know all about the Background and history clouds and the grasses, and why the leaves changed colour in the autumn; I watched the ants, bees, One of the most contentious issues of eight- birds, tadpoles, and caddisworms; I pestered people eenth-century natural history was with questions about what nobody knew or cared the disap- anything about". -

Sleat Housing Needs Survey

SLEAT HOUSING NEEDS SURVEY Thank to all those Sleat residents that returned the surveys and to Highland Council, Fearann Eilean Iarmain, Sabhal Mor Ostaig and Lochalsh and Skye Housing Association for agreeing to part fund this report. Sleat Housing Needs Survey 2014 | Rural Housing Scotland | Our Island Home !1 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Executive Summary .....................................................................................................4 1.0. Introduction ......................................................................................................6 1.1. Purpose of Study .....................................................................................................6 1.2. Methodology ............................................................................................................6 1.3 Literature Review & Data Analysis .........................................................................6 2.0. Area Profile ........................................................................................................7 2.1. Population ...............................................................................................................8 2.2. Households ...............................................................................................................8 2.3. Education ................................................................................................................9 2.4. Employment ............................................................................................................9 -

A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: an Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 1992 A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Utz, Hans (1992) "A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 27: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hans UIZ A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture The book Voyage en Ecosse et aux Iles Hebrides by Louis-Albert Necker de Saussure of Geneva is the basis for my report.! While he was studying in Edinburgh he began his private "discovery of Scotland" by recalling the links existing between the foreign country and his own: on one side, the Calvinist church and mentality had been imported from Geneva, while on the other, the topographic alternation between high mountains and low hills invited comparison with Switzerland. Necker's interest in geology first incited his second step in discovery, the exploration of the Highlands and Islands. Presently his ethnological curiosity was aroused to investigate a people who had been isolated for many centuries and who, after the abortive Jacobite Re bellion of 1745-1746, were confronted with the advanced civilization of Lowland Scotland, and of dominant England. -

Witch-Hunting and Witch Belief in the Gidhealtachd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten Henderson, L. (2008) Witch-hunting and witch belief in the Gàidhealtachd. In: Goodare, J. and Martin, L. and Miller, J. (eds.) Witchcraft and Belief in Early Modern Scotland. Palgrave historical studies in witchcraft and magic . Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 95-118. ISBN 9780230507883 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/7708/ Deposited on: 1 April 2011 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 CHAPTER 4 Witch-Hunting and Witch Belief in the Gàidhealtachd Lizanne Henderson In 1727, an old woman from Loth in Sutherland was brought before a blazing fire in Dornoch. The woman, traditionally known as Janet Horne, warmed herself, thinking the fire had been lit to take the chill from her bones and not, as was actually intended, to burn her to death. Or so the story goes. This case is well known as the last example of the barbarous practice of burning witches in Scotland. It is also infamous for some of its more unusual characteristics – such as the alleged witch ‘having ridden upon her own daughter’, whom she had ‘transformed into a pony’, and of course, the memorable image of the poor, deluded soul warming herself while the instruments of her death were being prepared. Impressive materials, though the most familiar parts of the story did not appear in print until at least 92 years after the event!1 Ironically, although Gaelic-speaking Scotland has been noted for the relative absence of formal witch persecutions, it has become memorable as the part of Scotland that punished witches later than anywhere else. -

Armadale Youth Hostel Ardvasar, Sleat Offers Over £185,000 Isle Of

Armadale Youth Hostel Ardvasar, Sleat Offers Over £185,000 Edinburgh • Oban • Bridge of Allan Isle of Skye IV45 8RS T: 0131 477 6001 [email protected] www.dmhbl.co.uk A detached dwelling in a wonderful elevated site offering Location Located in the Southern point of superb views across the Sound of Sleat to the mainland. the Isle of Skye, Ardvasar has an important ferry link to Mallaig and the mainland, as well as road links Description throughout the island via the Situated on the beautiful Isle of Skye, Armadale Youth Hostel is located less than one mile A851 and the A87. Within the from the village of Ardvasar and has almost immediate access via the ferry to the mainland. village is the Ardvasar Hotel dating The Hostel is situated in a wonderful elevated setting overlooking Armadale Bay and the from the 19th Century and also Sound of Sleat. With stunning views to the mainland, the Youth Hostel has potential to be the famous Armadale Castle with converted into a small Bed & Breakfast or used as a residential dwelling, subject to planning is gardens and museums, set in consents. the heart of a 20.000 acre highland estate. The Youth Hostel has 11 – 12 rooms and is set within private grounds, and the accommodation is formed over three levels. There is a large veranda to the front, side and The island is a popular tourist rear, from which the spectacular views can be appreciated, along with further garden destination for those wishing to grounds surrounding the Youth Hostel itself. -

Scotland-The-Isle-Of-Skye-2016.Pdf

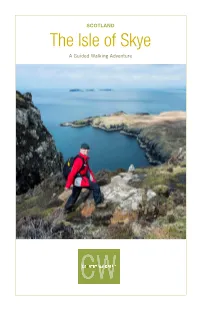

SCOTLAND The Isle of Skye A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Scotland at a Glance .............................................................. 22 Packing List ........................................................................... 26 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our new optional Flight + Tour Combo and PrePrePre-Pre ---TourTour Edinburgh Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. Overview Unparalleled scenery, incredible walks, local folklore, and history come together effortlessly in the Highlands and -

'Here Chapman Billies Tak Their Stand': a Pilot Study of Scottish Chapmen

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 120 (1990), 173-188 'Here chapman billie theik sta r stand' pilo:a t studf yo Scottish chapmen, packmen and pedlars Roger Leitch* INTRODUCTION Whereas kailyard literature has left a lasting, though somewhat stereotyped, picture of the travelling packman, his predecessor, the chapman, remains a marginal figure in Scottish society. At worst the chapman is completely ignored, his role often dismissed in a couple of sentences. The word 'chapman', meaning 'a pett itineranr yo t merchan dealer'r o t rars i ,Scotlan n ei d unti late lth e 16th century (DOST). The derivation is probably from the Old English chapman: ceap meaning barter or dealing bartero wh dealr ,n so thu ma s sa (OED). Variant wore th f dso have been trace Englann di d fro fas ma r nint e bacth s hka century (ibid). t woulI d thus appear unlikely tha Scottisa t h equivalent should only emerge seven centuries later. The Leges Burgorum and surviving fragments of ancient customary law contain references to chapmen prototypes known by interchangeable terms such as 'dustiefute', 'farandman' and 'pipouderus'. Skene interprets 'dustiefute 'ans a ' e pedde cremarr ro certain,a quhn s ahe e dwelling place quhare he may dicht the dust from his feet' (1774,432). This clearly indicates a form of itinerant pedlar or dealer in small wares. 'Pipouderus' is a Scotticism derived from piepowder, which in turn seems to have been an anglicization of the Old French for pedlar, piedpouldre. A note in Kames's Statute Law suggests that traces of the old piepowder court were found in Scotland (Kames 1774, 424). -

Local Studies Vol. 12: an T-Eilean Sgitheanach: Port Rìgh, an Srath

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol. 12 : An t-Eilean Sgitheanach: Port Rìgh, An Srath & Slèite 2 nd Edition Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1 Vol. 12: An t-Eilean Sgitheanach: Port Rìgh, An Srath & Slèite (Isle of Skye: Portree, Strath & Sleat) Author: Kurt C. Duwe 2nd Edition April, 2006 Executive Summary This publication is part of a series dealing with local communities which were predominantly Gaelic- speaking at the end of the 19 th century. Based mainly (but not exclusively) on local population census information the reports strive to examine the state of the language through the ages from 1881 until to- day. The most relevant information is gathered comprehensively for the smallest geographical unit pos- sible and provided area by area – a very useful reference for people with interest in their own commu- nity. Furthermore the impact of recent developments in education (namely teaching in Gaelic medium and Gaelic as a second language) is analysed for primary school catchments. The Isle of Skye has been a Gaelic-speaking stronghold for centuries. After World War II decline set in especially in the main townships of Portree, Broadford and Kyleakin. However, in recent years a re- markable renaissance has taken place with a considerable success in Gaelic-medium education and of course the establishment and growth of the Gaelic further education college at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig on the Sleat peninsula. Foundations have now been laid for a successful regeneration of Gaelic in the south- eastern parts of the Isle of Skye. However, there is still much room for improvement especially in the pre-school sector and in a few locations like Raasay where Gaelic has shown a dramatic decline recently.