Battered Women in Henley's Crimes of the Heart and Shepard's a Lie of the Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Drake Plays 1927-2021.Xls

Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls TITLE OF PLAY 1927-8 Dulcy SEASON You and I Tragedy of Nan Twelfth Night 1928-9 The Patsy SEASON The Passing of the Third Floor Back The Circle A Midsummer Night's Dream 1929-30 The Swan SEASON John Ferguson Tartuffe Emperor Jones 1930-1 He Who Gets Slapped SEASON Miss Lulu Bett The Magistrate Hedda Gabler 1931-2 The Royal Family SEASON Children of the Moon Berkeley Square Antigone 1932-3 The Perfect Alibi SEASON Death Takes a Holiday No More Frontier Arms and the Man Twelfth Night Dulcy 1933-4 Our Children SEASON The Bohemian Girl The Black Flamingo The Importance of Being Earnest Much Ado About Nothing The Three Cornered Moon 1934-5 You Never Can Tell SEASON The Patriarch Another Language The Criminal Code 1935-6 The Tavern SEASON Cradle Song Journey's End Good Hope Elizabeth the Queen 1936-7 Squaring the Circle SEASON The Joyous Season Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls Moor Born Noah Richard of Bordeaux 1937-8 Dracula SEASON Winterset Daugthers of Atreus Ladies of the Jury As You Like It 1938-9 The Bishop Misbehaves SEASON Enter Madame Spring Dance Mrs. Moonlight Caponsacchi 1939-40 Laburnam Grove SEASON The Ghost of Yankee Doodle Wuthering Heights Shadow and Substance Saint Joan 1940-1 The Return of the Vagabond SEASON Pride and Prejudice Wingless Victory Brief Music A Winter's Tale Alison's House 1941-2 Petrified Forest SEASON Journey to Jerusalem Stage Door My Heart's in the Highlands Thunder Rock 1942-3 The Eve of St. -

Member/Audience Play Suggestions 2012-13

CURTAIN PLAYERS 2012-2013 plays suggested by patrons/members Title Author A Poetry Reading (Love Poetry for Valentines Day) Agnes of God All My Sons (by 3 people) Arthur Miller All The Way Home Tad Mosel Angel Street Anything by Pat Cook Pat Cook Apartment 3A Jeff Daniels Arcadia Tom Stoppard As Bees in Honey Drown Assassins Baby With The Bathwater (by 2 people) Christopher Durang Beyond Therapy Christopher Durang Bleacher Bums Blythe Spirit (by 2 people) Noel Coward Butterscotch Cash on Delivery Close Ties Crimes of the Heart Beth Henley Da Hugh Leonard Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (by 2 people) Jeffrey Hatcher Driving Miss Daisy Equus Peter Shaffer Farragut North Beau Willimon Frankie and Johnny in the Claire De Lune Terrence McNally God's Country Happy Birthday, Wanda June Kurt Vonnegut I Never Saw Another Butterfly Impressionism Michael Jacobs Laramie Project Leaving Iowa Tim Clue/Spike Manton Lettice and Lovage (by 2 people) Lombardi Eric Simonson LuAnn Hampton Laverty Oberlander Mr and Mrs Fitch Douglas Carter Beane 1 Night Mother No Exit Sartre Picnic William Inge Prelude to A Kiss (by 2 people) Craig Lucas Proof Red John Logan Ridiculous Fraud Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (by 2 people) Tom Stoppard Sabrina Fair Samuel Taylor Second Samuel Pamela Parker She Loves Me Sheer Madness Side Man Warren Leight Sin Sister Mary Ignatius/Actor's Nightmare Christopher Durang Smoke on the Mountain (by 3 people) That Championship Season Jason Miller The 1940's Radio Hour Walton Jones The Caine Mutiny Court Martial The Cinderella Waltz The Country Girl Clifford Odets The Heidi Chronicles The Increased Difficulty of Concentration Vaclav Havel The Little Foxes Lillian Hellman The Man Who Came To Dinner Kaufman and Hart The Miser Moliere The Normal Heart Larry Kramer The Odd Couple Neil Simon The Passion of Dracula The Royal Family Kaufman and Ferber The Shape of Things LaBute The Substance of Fire Jon Robin Baitz The Tempest Shakespeare The Woolgatherer Three Days of Rain Richard Greenberg Tobacco Road While The Lights Were Out Wit 2 3 . -

Crimes of the Heart

1/12/2011 Crimes of the Heart Back to Ray Luo's Reviews Crimes of the Heart We've seen Shakespeare's "Measure for Measure" performed with a high tech cast taking place in the future. We've seen Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman" staged by high school drama students situated in Medieval Europe. The setting of a play doesn't matter, and nor should the composition of its cast. Leslie Ishii's recent production of Beth Henley's Pulitzer prize winning "Crimes of the Heart" is a testament that Asian Americans can play Southern ladies and gents, imitating not only their looks and expressions, but their attitudes and mentality to perfection. Lenny Magrath (Elizabeth Liang) is a 30 year old virgin who has been spending her birthdays alone with a single candle for a while. Her only birthday gift this time around is a box of old crappy chocolates from her friend Chick Boyle (Hiwa Bourne). Boyle is worried that Meg Magrath (Kimiko Gelman) is coming back to visit Lenny and seeing their father, who has been comatose at the hospital. Boyle never had a good relationship with Meg, who, as the family's most promising child with a singing career, has had many lovers and opportunities. Meg comes home to see Babe Botrelle (Maya Erskine), who has just been released on bail after shooting her husband in the stomach because she claims she "doesn't like his looks." When the three best friends Meg, Babe, and Lenny get together, they reminisce about the past and hope best for the future, even though for Babe, the future could lead to jail time, and she may not be able to take it anymore. -

William & Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM & MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Ann Arbor Civic Theatre PRESENTS

------ --Alct Ann Arbor Civic Theatre PRESENTS: [ ' MICHIGAN COMMERCE BANK Ann Arbor Civic Theatre Board of Directors Advisory Board Darrell W. Pierce-President Lisamarie Babik-Vice President Anne Bauman - Chair Kevin Salley-Treasurer JohnEman Jean Leverich-Secretary Robert Green Fred Patterson-Treasurer Emeritus David Keren Brittany Batell Ron Miller David Beaulieu Deanna Relyea Kathleen Beardmore Judy Dow Rumelhart Joyce Casale Ingrid Sheldon Paul Cumming Gayle Steiner Rob Goren Keith Taylor Heather Liebal Sheryl Yengera Matthew Rogers Michele K. Desvignes Schilling Cynthia Straub Ken Thomson Eileen Goldman Suzi Peterson Office Manager Managing Director January Provenzola Volunteer Coordinator Cassie Mann Laura Bird Program Director Shop Supervisor 322 WEST ANN STREET ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48104 box office (734) 971-2228 office (734) 971-0605 WWW.A2CT.ORG Ann Arbor Civic Theatre Opening night March 10, 2011 Arthur Miller Theatre DOUBT: A PARABLE Written by John Patrick Shanley Originally produced by the Manhattan Theatre Club on November 23,2004. Directed by Matt Martello Assistant Director Producer Stage Manager Alexa Ducsay Brenda Casher Alexa Ducsay Set Design Sound Design Lighting Design Matt Martello & Julian J ocque Nick Spencer Mishael Bingham Costume Design Technical Supervisor Properties Master Penny LaMauvais Thorn Johnson Michael Rudowski Graphic Design House Manager Brodie Brockie Sharon Guyton Cast Photographer Publicity Photographer Caleb Newman Tom Steppe Produced through special arrangement with Dramatists Play Serivce, Inc., New York NY I would like to personally welcome you to this performance of]ohn Patrick Shanley's Doubt, a Parable. This is by far one of my favorite newer scripts. I'd like to take a few minutes to try and explain why. -

Dakota Stage Ltd. Past Productions

Dakota Stage Ltd. Past Productions SEASON ONE 1979-1980 SEPT. 1979 PLAZA SUITE NOV. 1979 TEN LITTLE INDIANS FEB. 1980 SIDE BY SIDE BY SONDHEIM MAY. 1980 BAREFOOT IN THE PARK SEASON TWO 1980-1981 SEPT. 1980 BLITHE SPIRIT OCT. 1980 THE FANTASTICKS DEC. 1980 A CHRISTMAS CAROL FEB. 1981 SAME TIME, NEXT YEAR MAY. 1981 UP ROSE A BURNING MAN SEASON THREE 1981-1982 OCT. 1981 VANITIES DEC. 1981 ANYTHING GOES FEB. 1982 THE GOOD DOCTOR MAY. 1982 THE RUNNER STUMBLES SUMMER 1982 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON FOUR 1982-1983 OCT. 1982 6 ROOMS RIVER VIEW DEC. 1982 WAIT UNTIL DARK MARCH. 1983 EQUUS MAY. 1983 ROGERS & HART SUMMER 1983 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON FIVE 1983-1984 SEPT. 1983 THE FOUR POSTER NOV. 1983 LUV FEB. 1984 SEE HOW THEY RUN APRIL. 1984 THE SHADOW BOX SUMMER 1984 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON SIX 1984-1985 SEPT. 1984 SLEUTH NOV. 1984 LOVERS & OTHER STRANGERS FEB. 1985 JACQUES BREL IS ALIVE AND LIVING IN PARIS MARCH. 1985 FRAGMENTS APRIL. 1985 DIAL M FOR MURDER SUMMER 1985 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON SEVEN 1985-1986 OCT. 1985 YOU KNOW I CAN'T HEAR YOU WHEN THE WATER IS RUNNING NOV. 1985 PLAY IT AGAIN SAM FEB. 1986 AGNES OF GOD MARCH. 1986 ROMANTIC COMEDY SUMMER 1986 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON EIGHT 1986-1987 SEPT. 1986 DEATHTRAP NOV. 1986 MASS APPEAL FEB. 1987 THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING ERNEST MARCH. 1987 THE PUBLIC EYE APRIL. 1987 THE LECHER & THE ROSE SUMMER 1987 FORT LINCOLN WALKING DRAMA SEASON NINE 1987-1988 OCT. -

Drama Winners the First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No Award Given 1965 the Subject Was Roses by Frank D

The Pulitzer Prizes Drama Winners The First 50 Years: 1917-1966 Pulitzer Drama Checklist 1966 No award given 1965 The Subject Was Roses by Frank D. Gilroy 1964 No award given 1963 No award given 1962 How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying by Loesser and Burrows 1961 All the Way Home by Tad Mosel 1960 Fiorello! by Weidman, Abbott, Bock, and Harnick 1959 J.B. by Archibald MacLeish 1958 Look Homeward, Angel by Ketti Frings 1957 Long Day’s Journey Into Night by Eugene O’Neill 1956 The Diary of Anne Frank by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich 1955 Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams 1954 The Teahouse of the August Moon by John Patrick 1953 Picnic by William Inge 1952 The Shrike by Joseph Kramm 1951 No award given 1950 South Pacific by Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II and Joshua Logan 1949 Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller 1948 A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams 1947 No award given 1946 State of the Union by Russel Crouse and Howard Lindsay 1945 Harvey by Mary Coyle Chase 1944 No award given 1943 The Skin of Our Teeth by Thornton Wilder 1942 No award given 1941 There Shall Be No Night by Robert E. Sherwood 1940 The Time of Your Life by William Saroyan 1939 Abe Lincoln in Illinois by Robert E. Sherwood 1938 Our Town by Thornton Wilder 1937 You Can’t Take It With You by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman 1936 Idiot’s Delight by Robert E. Sherwood 1935 The Old Maid by Zoë Akins 1934 Men in White by Sidney Kingsley 1933 Both Your Houses by Maxwell Anderson 1932 Of Thee I Sing by George S. -

Crimes of the Heart PLAYWRIGHT Beth Henley

C T3 PEOPLE DEPENDABLE AS TEXAS 1 WEATHER ISN T. BOARD OF DIRECTORS CHAIR Enika Schulze LIAISON, CITY OF DALLAS CULTURAL COMMISSION Sam Yang Jae Alder, D'Metria Benson, NancyCochran, PETE DELKUS DELIVERS. Roland BlVirginia Dykes, GaryW. Grubbs, David G. Luther, Sonja J. McGill, Patsy P. Yung Micale, Jean M. Nelson, Shanna Nugent, Valerie Pelan, Vicki L. A Class Act !NEWS�:�CJD WEATHER. Reid, Elizabeth Rivera, Eileen Rosenblum, PhD, Janet Spencer Shaw, Ann Stuart, PhD, Katherine From firstact to finalbow, Ward, Karen Washington, Linda Zimmerman WFAA.COM begin or end your evening FOR DINING RESERVATIONS with the exceptional service and ADMINISTRATION 214.720.5249 cuisine at the legendary Pyramid EXECUTIVE PRODUCER-DIRECTOR Jae Alder Grill. Extend your meal into a FOR OVERNIGHT COMPANY MANAGER Terry Dobson ACCOMMODATIONS long weekend in any one of our 214.720.5290 ASSISTANT PRODUCER Cory Norman newly remodeled luxury guest DIRECTOR OF BUSINESS AFFAIRS Joan Sleight rooms and sujtes including our new upscale "Fairmont Gold" IN-HOUSE ACCOUNTANTWendy Kwan accommodations opening in DI RECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS 6{_COMMUN !CATIONS early 2008. Kimberly Richard INTERN SUPERVISOR MarkC, Guerra 1717 N Akard St D::dlas, Texas 75201 www.foirmont corn/dallas EXECUTIVE ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Adele Acrey PRODUCTION TECHNICAL DIRECTOR DavidWalsh MUSICAL DI RECTOR Terry Dobson RESIDENT ARTIST Bruce R. Coleman MASTER CARPENTER Jeffrey Schmidt INTERN STAFF Paul Arnold, Maryam Baig, Stacie Cleland CUSTOMER SERVICE CUSTOM ER SERVICE DI RECTOR Amy Mills Jackson HOUSE MANAGER Nancy Meeks BOX OFFICE DAYTIME SERVICE MANAGER Darius Warren BOX OFFICE AGENTS Tony Banda, Fred Faust, Silvia Martinez, Chris Sanders DIRECTOR OF TELEMARKETING Carol Crosby TELEMARKETING AGENTS Don Baab, Deborah Byrd, Trinity Johannsen, Natha Taylor, Roger Wilson DIRECTOR OF SPECIAL MARKETING Trinity Johannsen ,. -

Department of Theatre & Dance

Western Kentucky University Department of Theatre & Dance Mainstage Production Record 2017-2018 THESE SHINING LIVES MOTHER COUAGE AND HER CHILDREN WINTERDANCE: ‘TIS THE SEASON NEW WORKS FESTIVAL 2018 9 TO 5 EVENING OF DANCE 2016-2017 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS WINTERDANCE Featuring Adventures in Toyland DOG SEES GOD: CONFESSIONS OF A TEENAGE BLOCKHEAD A PAIR OF PUCCINIS! Suor Angelica and Gianni Schicchi (w/Department of Music) EVENING OF DANCE 2015-2016 OUR TOWN INTO THE WOODS A HOLIDAY EXTRAVAGANZA Featuring Sleeping Beauty GUYS AND DOLLS (w/Department of Music) NEW WORKS FESTIVAL 2016 EVENING OF DANCE 2014-2015 SIX CHARACTERS IN SEARCH OF AN AUTHOR THE 25TH ANNUAL PUTNAM COUNTY SPELLING BEE A HOLIDAY EXTRAVAGANZA Featuring Cinderella and Friends THE HATMAKERS WIFE THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO (w/Department of Music) EVENING OF DANCE 2013-2014 CRIMES OF THE HEART THE COMEDY OF ERRORS WINTERDANCE CURTAINS (w/Department of Music) NEW WORKS FESTIVAL EVENING OF DANCE 2012-2013 LES LIAISONS DANGEREUSES URINETOWN WINTERDANCE PIRATES OF PENZANCE (w/Department of Music) DEAD MAN’S CELL PHONE EVENING OF DANCE 2011 – 2012 NOISES OFF AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS and GIFT OF THE MAGI (w/Department of Music) WINTERDANCE: A HOLIDAY EXTRAVAGANZA OKLAHOMA! STOP KISS EVENING OF DANCE 2010-2011 BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (w/Department of Music) MACBETH WINTERDANCE KHAMASEEN A TASTE OF HONEY AN EVENING OF DANCE 2009-2010 THE ECCENTRICITIES OF A NIGHTINGALE PUTTING IT TOGETHER WINTERDANCE AN EVENING OF CHAMBER OPERAS (w/Department of Music) EMPTIES -

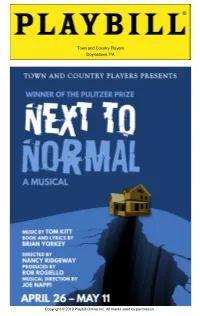

Next to Normal

Town and Country Players Doylestown, PA Copyright © 2019 Playbill Online Inc. All marks used by permission. Town and Country Players PRESENTS NEXT TO NORMAL Music by Book and Lyrics by Tom Kitt Brian Yorkey with Nicole Telesco Melissa Angelo-Schiumo John Yankavich Adam Zucal Brian Jason Kelly Sean O'Neill Lighting Designer Musical Director Lighting Designer Walter Hauck Joe Nappi Anne Schmitt Set Designer Stage Manager Scenic Designer Jon Knapp Jim McIntosh T. Mark Cole Asst. Stage Manager Emme O'Reilly Produced by Rob Rosiello Directed by Nancy Ridgeway Next to Normal is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. 423 West 55th Street, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10019. Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684 www.mtishows.com Copyright © 2019 Playbill Online Inc. All marks used by permission. T&C WANTS YOU TO KNOW... SETTING TIME: PRESENT DAY LOCATION: PORTLAND, OREGON This show contains Mature Language and Content and may not be suitable for children under the age of 13. Please note that portions of the lighting for this show contain a simulated strobe light effect. CRISIS HOTLINES National suicide prevention hotline: 1-800-273-8255 Mental health hotline: 1-888-613-6928 Substance abuse: 855-789-9197 PTSD: 1-877-726-4727 Copyright © 2019 Playbill Online Inc. All marks used by permission. T&C WANTS YOU TO KNOW... Director’s Note – Next to Normal I am proud and honored to be at the helm of Next to Normal. Presenting this show to open our 72nd Town & Country Players Season continues the theater’s trend toward offering Bucks County audiences compelling, thought provoking experiences that go well beyond a fun night out at the theater.