Topography of the Histone Octamer Surface: Repeating Structural Motifs Utilized in the Docking of Nucleosomal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Datasheet for Histone H2B Human, Recombinant (M2505; Lot 0031404)

Supplied in: 20 mM Sodium Phosphate (pH 7.0), Quality Control Assays: Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry). The Histone H2B 300 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. SDS-PAGE: 0.5 µg, 1.0 µg, 2.0 µg, 5.0 µg, average mass calculated from primary sequence Human, Recombinant 10.0 µg Histone H2B Human, Recombinant were is 13788.97 Da. This confirms the protein identity Note: The protein concentration (1 mg/ml, 73 µM) loaded on a 10–20% Tris-Glycine SDS-PAGE gel as well as the absence of any modifications of the is calculated using the molar extinction coefficient and stained with Coomassie Blue. The calculated histone. 1-800-632-7799 for Histone H2B (6400) and its absorbance at molecular weight is 13788.97 Da. Its apparent [email protected] 280 nm (3,4). 1.0 A units = 2.2 mg/ml N-terminal Protein Sequencing: Protein identity 280 molecular weight on 10–20% Tris-Glycine SDS- www.neb.com was confirmed using Edman Degradation to PAGE gel is ~17 kDa. M2505S 003140416041 Synonyms: Histone H2B/q, Histone H2B.1, sequence the intact protein. Histone H2B-GL105 Mass Spectrometry: The mass of purified Histone H2B Human, Recombinant is 13788.5 Da Protease Assay: After incubation of 10 µg of M2505S B r kDa 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 as determined by ESI-TOF MS (Electrospray Histone H2B Human, Recombinant with a standard 250 4.0 mixture of proteins for 2 hours at 37°C, no 100 µg 1.0 mg/ml Lot: 0031404 150 13788.5 100 proteolytic activity could be detected by SDS- RECOMBINANT Store at –20°C Exp: 4/16 80 PAGE. -

Functional Domains for Assembly of Histones H3 and H4 Into the Chromatin of Xenopus Embryos

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 93, pp. 12780–12785, November 1996 Biochemistry Functional domains for assembly of histones H3 and H4 into the chromatin of Xenopus embryos LITA FREEMAN,HITOSHI KURUMIZAKA, AND ALAN P. WOLFFE* Laboratory of Molecular Embryology, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892-2710 Communicated by Stuart L. Schreiber, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, September 3, 1996 (received for review May 31, 1996) ABSTRACT Histones H3 and H4 have a well defined Modification of the N-terminal tail of H4 by acetylation has structural role in the nucleosome and an established role in been correlated with both transcription (25, 26) and nucleo- the regulation of transcription. We have made use of a some assembly (27, 28). Direct evidence for a causal role for microinjection strategy using Xenopus embryos to define the H4 acetylation in these events is, however, yet to be estab- minimal structural components of H3 and H4 necessary for lished. Tryptic removal of the N-terminal tail of histone H4 nucleosome assembly into metazoan chromosomes in vivo.We from the nucleosome or acetylation of the tail does not find that both the N-terminal tail of H4, including all sites of influence the helical periodicity of DNA in the nucleosome but acetylation, and the C-terminal a-helix of the H4 histone fold might influence the exact path taken by the double helix as it domain are dispensable for chromatin assembly. The N- wraps around the histone fold domains of the core histones (29, terminal tail and an N-terminal a-helix of H3 are also 30). -

Chapter 6 Protein Structure and Folding

Chapter 6 Protein Structure and Folding 1. Secondary Structure 2. Tertiary Structure 3. Quaternary Structure and Symmetry 4. Protein Stability 5. Protein Folding Myoglobin Introduction 1. Proteins were long thought to be colloids of random structure 2. 1934, crystal of pepsin in X-ray beam produces discrete diffraction pattern -> atoms are ordered 3. 1958 first X-ray structure solved, sperm whale myoglobin, no structural regularity observed 4. Today, approx 50’000 structures solved => remarkable degree of structural regularity observed Hierarchy of Structural Layers 1. Primary structure: amino acid sequence 2. Secondary structure: local arrangement of peptide backbone 3. Tertiary structure: three dimensional arrangement of all atoms, peptide backbone and amino acid side chains 4. Quaternary structure: spatial arrangement of subunits 1) Secondary Structure A) The planar peptide group limits polypeptide conformations The peptide group ha a rigid, planar structure as a consequence of resonance interactions that give the peptide bond ~40% double bond character The trans peptide group The peptide group assumes the trans conformation 8 kJ/mol mire stable than cis Except Pro, followed by cis in 10% Torsion angles between peptide groups describe polypeptide chain conformations The backbone is a chain of planar peptide groups The conformation of the backbone can be described by the torsion angles (dihedral angles, rotation angles) around the Cα-N (Φ) and the Cα-C bond (Ψ) Defined as 180° when extended (as shown) + = clockwise, seen from Cα Not -

A Mutation in Histone H2B Represents a New Class of Oncogenic Driver

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on July 23, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0393 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. A Mutation in Histone H2B Represents A New Class Of Oncogenic Driver Richard L. Bennett1, Aditya Bele1, Eliza C. Small2, Christine M. Will2, Behnam Nabet3, Jon A. Oyer2, Xiaoxiao Huang1,9, Rajarshi P. Ghosh4, Adrian T. Grzybowski5, Tao Yu6, Qiao Zhang7, Alberto Riva8, Tanmay P. Lele7, George C. Schatz9, Neil L. Kelleher9 Alexander J. Ruthenburg5, Jan Liphardt4 and Jonathan D. Licht1 * 1 Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Florida Health Cancer Center, Gainesville, FL 2 Division of Hematology/Oncology, Northwestern University 3 Department of Cancer Biology, Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Department of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, Harvard Medical School 4 Department of Bioengineering, Stanford University 5 Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago 6 Department of Chemistry, Tennessee Technological University 7 Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Florida 8 Bioinformatics Core, Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research, University of Florida 9 Department of Chemistry, Northwestern University, Evanston IL 60208 Running title: Histone mutations in cancer *Corresponding Author: Jonathan D. Licht, MD The University of Florida Health Cancer Center Cancer and Genetics Research Complex, Suite 145 2033 Mowry Road Gainesville, FL 32610 352-273-8143 [email protected] Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare Downloaded from cancerdiscovery.aacrjournals.org on September 27, 2021. © 2019 American Association for Cancer Research. Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on July 23, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0393 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. -

And Beta-Helical Protein Motifs

Soft Matter Mechanical Unfolding of Alpha- and Beta-helical Protein Motifs Journal: Soft Matter Manuscript ID SM-ART-10-2018-002046.R1 Article Type: Paper Date Submitted by the 28-Nov-2018 Author: Complete List of Authors: DeBenedictis, Elizabeth; Northwestern University Keten, Sinan; Northwestern University, Mechanical Engineering Page 1 of 10 Please doSoft not Matter adjust margins Soft Matter ARTICLE Mechanical Unfolding of Alpha- and Beta-helical Protein Motifs E. P. DeBenedictis and S. Keten* Received 24th September 2018, Alpha helices and beta sheets are the two most common secondary structure motifs in proteins. Beta-helical structures Accepted 00th January 20xx merge features of the two motifs, containing two or three beta-sheet faces connected by loops or turns in a single protein. Beta-helical structures form the basis of proteins with diverse mechanical functions such as bacterial adhesins, phage cell- DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x puncture devices, antifreeze proteins, and extracellular matrices. Alpha helices are commonly found in cellular and extracellular matrix components, whereas beta-helices such as curli fibrils are more common as bacterial and biofilm matrix www.rsc.org/ components. It is currently not known whether it may be advantageous to use one helical motif over the other for different structural and mechanical functions. To better understand the mechanical implications of using different helix motifs in networks, here we use Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) simulations to mechanically unfold multiple alpha- and beta- helical proteins at constant velocity at the single molecule scale. We focus on the energy dissipated during unfolding as a means of comparison between proteins and work normalized by protein characteristics (initial and final length, # H-bonds, # residues, etc.). -

Effect of Superhelical Structure on the Secondary Structure of DNA Rings

VOL. 5, PP. 691-696 (1967) Effect of Superhelical Structure on the Secondary Structure of DNA Rings DANIEL GLAUBIGER and JOHN E. HEARST, Departnient of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley, California Synopsis A quantity, called the linking number, is defined, which specifies the total number of t,wists in a circular helix. The linking number is invariant under continuous deforma- tions of the ring and therefore enables one to calculate the influence of superhelical structures on the secondary helix of a circular molecule. The linking number can be determined by projecting the helix into a plane and counting strand crosses in the projection as described. For example, it has been shown that for each 180" twist in a left-handed superhelix, a right-handed 360" twist is removed from the secondary helix, thus allowing local unwinding. Introduction It is of interest to relate superhelical structure of helical molecules to their secondary structure.' By defining a quantity characteristic of two- stranded circular helical niolecules, related to the helical structure, and in- variant under continuous deformations of the molecule, we are able to evaluate the changes in helical structure brought about by the imposition of superhelical configurations on such molecules. The quantity of interest, called the linking number, is related to the number of turns/cycle for a circular helical molecule.* It will be shown that superhelical structures which are made from helical polymers con- tribute to this number and alter the contribution made by the secondary structure of the molecule to this number. This is made manifest as a change in the number of turns/cycle or as a change in the number of turns/ unit length. -

Influence of the Sequence-Dependent Flexure of DNA on Transcription in E.Coli

Volume 17 Number 22 1989 Nucleic Acids Research Influence of the sequence-dependent flexure of DNA on transcription in E.coli Christina M.Collis, Peter L.Molloy, Gerald W.Both and Horace R.Drew* CSIRO Division of Biotechnology, Laboratory for Molecular Biology, PO Box 184, North Ryde, NSW 2113, Australia Received August 11, 1989; Revised and Accepted October 20, 1989 ABSTRACT In order to study the effects of DNA structure on cellular processes such as transcription, we have made a series of plasmids that locate several different kinds of DNA structure (stiff, flexible or curved) near the sites of cleavage by commonly-used restriction enzymes. One can use these plasmids to place any DNA region of interest (e.g., promoter, operator or enhancer) close to certain kinds of DNA structure that may influence its ability to work in a living cell. In the present example, we have placed a promoter from T7 virus next to the special DNA structures; the T7 promoter is then linked to a gene for a marker protein (chloramphenicol acetyl transferase). When plasmids bearing the T7 promoter are grown in cells of E. coli that contain T7 RNA polymerase, the special DNA structures seem to have little or no influence over the activity of the T7 promoter, contrary to our expectations. Yet when the same plasmids are grown in cells of E. coli that do not contain T7 RNA polymerase, some of the DNA structures show a surprising promoter activity of their own. In particular, the favourable flexibility or curvature of DNA, in the close vicinity of potential -35 and -10 promoter regions, seems to be a significant factor in determining where E. -

Chromatin Structure

Chromatin Structure Dr. Carol S. Newlon [email protected] ICPH E250P DNA Packaging Is a Formidable Challenge • Single DNA molecule in human chromosome ca. 5 cm long • Diploid genome contains ca. 2 meters of DNA • Nucleus of human cell ca. 5 µm in diameter • Human metaphase chromosome ca. 2.5 µm in length • 10,000 to 20,000 packaging ratio required Overview of DNA Packaging Packaging in Interphase Nucleus Chromatin Composition • Complex of DNA and histones in 1:1 mass ratio • Histones are small basic proteins – highly conserved during evolution – abundance of positively charged aa’s (lysine and arginine) bind negatively charged DNA • Four core histones: H2A, H2B, H3, H4 in 1:1:1:1 ratio • Linker histone: H1 in variable ratio Chromatin Fibers 11-nm fiber 30-nm fiber • beads = nucleosomes • physiological ionic • compaction = 2.5X strength (0.15 M KCl) • low ionic strength buffer • compaction = 42X • H1 not required • H1 required Micrococcal Nuclease Digestion of Chromatin Stochiometry of Histones and DNA • 146 bp DNA ca. 100 kDa • 8 histones ca 108 kDa • mass ratio of DNA:protein 1:1 Structure of Core Nucleosome 1.65 left handed turns of DNA around histone octamer Histone Structure Assembly of a Histone Octamer Nucleosomes Are Dynamic Chromatin Remodeling Large complexes of ≥ 10 proteins Use energy of ATP hydrolysis to partially disrupt histone-DNA contacts Catalyze nucleosome sliding or nucleosome removal 30-nm Chromatin Fiber Structure ?? Models for H1 and Core Histone Tails in Formation of 30-nm Fiber Histone Tails Covalent Modifications -

X-Ray Scattering from the Superhelix in Circular DNA (Supercoiling/Diffraction from Solutions/Specific Linking Difference/Writhe Vs

Proc. Nati Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 80, pp. 741-744, February 1983 Biophysics X-ray scattering from the superhelix in circular DNA (supercoiling/diffraction from solutions/specific linking difference/writhe vs. twist) G. W. BRADY*, D. B. FEIN*, H. LAMBERTSONt, V. GRASSIANt, D. Foost, AND C. J. BENHAMt Institute, Troy, New York 12181; *Center for Laboratories and Research, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York 12222; tRensselaer Polytechnic and tDepartment of Mathematics, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506 Communicated by Bruno H. Zimm, October 25, 1982 ABSTRACT This communication presents measurements, creased the lower angle limit of resolution of the instrument made with a newly constructed position-sensitive detector, of the because the inner portion of the scattering curve was super- small-angle x-ray scattering from the first-order superhelix ofna- imposed on a risingbackground resultingfrom parasitic slit scat- tive COP608 plasmid DNA. This instrument measures intensities tering. In consequence, the resulting data could not be de- free of slit effects and provides good resolution in the region of smeared, so a direct comparison with theory was precluded. interest. The reported observations, made both in the presence This paper presents measurements of SAS from the first-or- and in the absence of intercalator, closely fit the scattering pat- der ccc DNA superhelix made with a new position-sensitive terns calculated for noninterwound helical first-order superhel- detector (PSD). The resulting profiles are free of slit effects, ices. These results are consistent with a toroidal helical structure permitting direct and unambiguous comparisons with theory. but not with interwound conformations. -

DNA-Mediated Self-Assembly of Gold Nanoparticles on Protein Superhelix

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/449561; this version posted October 22, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. DNA-mediated self-assembly of gold nanoparticles on protein superhelix Tao Zhang∗,y,z and Ingemar Andréy yDepartment of Biochemistry and Structural Biology & Center for Molecular Protein Science, Lund University, P.O. Box 124, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden zCurrent address: Max-Planck-Institute for Intelligent Systems, Heisenbergstraße 3, D-70569 Stuttgart, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Recent advances in protein engineering have enabled methods to control the self- assembly of protein on various length-scales. One attractive application for designed proteins is to direct the spatial arrangement of nanomaterials of interest. Until now, however, a reliable conjugation method is missing to facilitate site-specific position- ing. In particular, bare inorganic nanoparticles tend to aggregate in the presence of buffer conditions that are often required for the formation of stable proteins. Here, we demonstrated a DNA mediated conjugation method to link gold nanoparticles with protein structures. To achieve this, we constructed de novo designed protein fibers based on previously published uniform alpha-helical units. DNA modification rendered gold nanoparticles with increased stability against ionic solutions and the use of com- plementary strands hybridization guaranteed the site-specific binding to the protein. The combination of high resolution placement of anchor points in designed protein assemblies with the increased control of covalent attachment through DNA binding 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/449561; this version posted October 22, 2018. -

Recurrent Evolution of DNA-Binding Motifs in the Drosophila Centromeric Histone

Recurrent evolution of DNA-binding motifs in the Drosophila centromeric histone Harmit S. Malik*, Danielle Vermaak*, and Steven Henikoff*†‡ †Howard Hughes Medical Institute, *Basic Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA 98109 Communicated by Stanley M. Gartler, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, December 12, 2001 (received for review October 29, 2001) All eukaryotes contain centromere-specific histone H3 variants being one of the most evolutionarily constrained classes of (CenH3s), which replace H3 in centromeric chromatin. We have eukaryotic proteins. Second, CenH3s are evolving adaptively, previously documented the adaptive evolution of the Drosophila presumably in concert with centromeres, which consist of the CenH3 (Cid) in comparisons of Drosophila melanogaster and Dro- most rapidly evolving DNA in the genome. sophila simulans, a divergence of Ϸ2.5 million years. We have Chromosomes (and their centromeres) may compete at mei- proposed that rapidly changing centromeric DNA may be driving osis I for inclusion into the oocyte (11). A centromeric satellite CenH3’s altered DNA-binding specificity. Here, we compare Cid expansion could bias centromeric strength, leading to preferred sequences from a phylogenetically broader group of Drosophila inclusion in the oocyte, but also to increased nondisjunction. A species to suggest that Cid has been evolving adaptively for at least subsequent alteration of CenH3’s DNA-binding preferences 25 million years. Our analysis also reveals conserved blocks not could restore parity among different chromosomes (2), thereby only in the histone-fold domain but also in the N-terminal tail. In alleviating the deleterious consequences of satellite drive. Suc- several lineages, the N-terminal tail of Cid is characterized by cessive rounds of satellite and CenH3 drive are detected as an subgroup-specific oligopeptide expansions. -

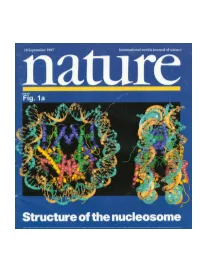

Crystal Structure of the Nucleosome Core Particle at 2.8Å Resolution Karolin Luger, Armin W

Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8Å resolution Karolin Luger, Armin W. Mader, Robin K. Richmond, David R Sargent & Timothy J. Richmond Institut fur Molekularbiologie und Biophysik ETHZ, ETH-Hönggerberg, CH-8093 Zürich, Switzerland Nature, Vol 389, pages 251-260 The X-ray crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle of chromatin shows in atomic detail how the histone protein octamer is assembled and how 146 base pairs of DNA are organized into a superhelix around it. Both histone/histone and histone/DNA interactions depend on the histone fold domains and additional, well ordered structure elements extending from this motif. Histone amino-terminal tails pass over and between the gyros of the DNA superhelix to contact neighboring particles. The lack of uniformity between multiple histone/DNA-binding sites causes the DNA to deviate from ideal superhelix geometry. DNA in chromatin is organized in arrays of nucleosomes (1). Two copies of each histone protein, H2A, H2B, H3 and H4, are assembled into an octamer that has 145-147 base pairs (bp) of DNA wrapped around it to form a nucleosome core (of relative molecular mass 206K). This highly conserved nucleoprotein complex occurs essentially every 200 ± 40 bp throughout all eukaryotic genomes (2). The repeating nucleosome cores further assemble into higher-order structures which are stabilized by the linker histone H1 and these compact linear DNA overall by a factor of 30-40. The nucleosome (nucleosome core, linker DNA and H1) thereby shapes the DNA molecule both at the atomic level through DNA bending, and on the much larger scale of genes by forming higher- order helices (3).