Pangolin, Rāma, and the Garden in Laṅkā in the 9Th Century CE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning About Mammals

Learning About Mammals The mammals (Class Mammalia) includes everything from mice to elephants, bats to whales and, of course, man. The amazing diversity of mammals is what has allowed them to live in any habitat from desert to arctic to the deep ocean. They live in trees, they live on the ground, they live underground, and in caves. Some are active during the day (diurnal), while some are active at night (nocturnal) and some are just active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular). They live alone (solitary) or in great herds (gregarious). They mate for life (monogamous) or form harems (polygamous). They eat meat (carnivores), they eat plants (herbivores) and they eat both (omnivores). They fill every niche imaginable. Mammals come in all shapes and sizes from the tiny pygmy shrew, weighing 1/10 of an ounce (2.8 grams), to the blue whale, weighing more than 300,000 pounds! They have a huge variation in life span from a small rodent living one year to an elephant living 70 years. Generally, the bigger the mammal, the longer the life span, except for bats, which are as small as rodents, but can live for up to 20 years. Though huge variation exists in mammals, there are a few physical traits that unite them. 1) Mammals are covered with body hair (fur). Though marine mammals, like dolphins and whales, have traded the benefits of body hair for better aerodynamics for traveling in water, they do still have some bristly hair on their faces (and embryonically - before birth). Hair is important for keeping mammals warm in cold climates, protecting them from sunburn and scratches, and used to warn off others, like when a dog raises the hair on its neck. -

PROCEEDINGS of the WORKSHOP on TRADE and CONSERVATION of PANGOLINS NATIVE to SOUTH and SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 June – 2 July 2008, Singapore Zoo Edited by S

PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP ON TRADE AND CONSERVATION OF PANGOLINS NATIVE TO SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 June – 2 July 2008, Singapore Zoo Edited by S. Pantel and S.Y. Chin Wildlife Reserves Singapore Group PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP ON TRADE AND CONSERVATION OF PANGOLINS NATIVE TO SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA 30 JUNE –2JULY 2008, SINGAPORE ZOO EDITED BY S. PANTEL AND S. Y. CHIN 1 Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2009 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in these proceedings is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in these proceedings do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Sandrine Pantel, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Sandrine Pantel and Chin Sing Yun (ed.). 2009. Proceedings of the Workshop on Trade and Conservation of Pangolins Native to South and Southeast Asia, 30 June-2 July -

Exploring the Natural Origins of SARS-Cov-2

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.22.427830; this version posted January 22, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Exploring the natural origins of SARS-CoV-2 1 1 2 3 1,* Spyros Lytras , Joseph Hughes , Wei Xia , Xiaowei Jiang , David L Robertson 1 MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (CVR), Glasgow, UK. 2 National School of Agricultural Institution and Development, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU), Suzhou, China. * Correspondence: [email protected] Summary. The lack of an identifiable intermediate host species for the proximal animal ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 and the distance (~1500 km) from Wuhan to Yunnan province, where the closest evolutionary related coronaviruses circulating in horseshoe bats have been identified, is fueling speculation on the natural origins of SARS-CoV-2. Here we analyse SARS-CoV-2’s related horseshoe bat and pangolin Sarbecoviruses and confirm Rhinolophus affinis continues to be the likely reservoir species as its host range extends across Central and Southern China. This would explain the bat Sarbecovirus recombinants in the West and East China, trafficked pangolin infections and bat Sarbecovirus recombinants linked to Southern China. Recent ecological disturbances as a result of changes in meat consumption could then explain SARS-CoV-2 transmission to humans through direct or indirect contact with the reservoir wildlife, and subsequent emergence towards Hubei in Central China. -

Structure and Binding Properties of Pangolin-Cov Spike Glycoprotein Inform the Evolution of SARS-Cov-2 ✉ ✉ Antoni G

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21006-9 OPEN Structure and binding properties of Pangolin-CoV spike glycoprotein inform the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 ✉ ✉ Antoni G. Wrobel 1,5 , Donald J. Benton 1,5 , Pengqi Xu2,1, Lesley J. Calder3, Annabel Borg4, ✉ Chloë Roustan4, Stephen R. Martin1, Peter B. Rosenthal 3, John J. Skehel1 & Steven J. Gamblin 1 1234567890():,; Coronaviruses of bats and pangolins have been implicated in the origin and evolution of the pandemic SARS-CoV-2. We show that spikes from Guangdong Pangolin-CoVs, closely related to SARS-CoV-2, bind strongly to human and pangolin ACE2 receptors. We also report the cryo-EM structure of a Pangolin-CoV spike protein and show it adopts a fully-closed conformation and that, aside from the Receptor-Binding Domain, it resembles the spike of a bat coronavirus RaTG13 more than that of SARS-CoV-2. 1 Structural Biology of Disease Processes Laboratory, Francis Crick Institute, NW1 1AT, London, UK. 2 Precision Medicine Center, The Seventh Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China. 3 Structural Biology of Cells and Viruses Laboratory, Francis Crick Institute, NW1 1AT, London, UK. 4 Structural Biology Science Technology Platform, Francis Crick Institute, NW1 1AT, London, UK. 5These authors contributed equally: Antoni G. ✉ Wrobel, Donald J. Benton. email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2021) 12:837 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21006-9 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21006-9 espite intensive research into the origins of the COVID- 19 pandemic, the evolutionary history of its causative A SARS-CoV-2 S D 1,2 agent SARS-CoV-2 remains unclear . -

Research Article the Placenta Anatomy of Sunda Porcupine (Hystrix Javanica)

Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences Research Article The Placenta Anatomy of Sunda Porcupine (Hystrix javanica) TEGUH BUDIPITOJO*, SITI SHOFIYAH, DIAN BEKTI HADI MASITHOH, LINDA MIFTAKHUL KHASANAH, IRMA PADETA Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia. Abstract | Sunda porcupines (Hystrix javanica) belongs to the Order of Rodentia is an endemic animal of Indonesia. The aims of this study are to determine the types and histological structure of Sunda porcupine placenta. Data regarding the type and histological structure of Sunda porcupines’ placental organs can be used to support the conservation of Sunda porcupines. This research used two samples of placenta Sunda Porcupine from Ngawi, East Java. Placenta were fixed in Bouin’s solution for 24 hours. Tissues were processed by using paraffin method and cut in 5 µm thickness. Tissues slide were stained with Hematoxylin Eosin (HE) to identified histological structure of the Sunda porcupine placenta. Photomicrographs were using Optilab Image Viewer. The histological structure of the Sunda porcupine’s placenta were analyzed and reported descriptively. Macroscopically, the shape of Sunda Porcupine placenta is flat like a disc. Histologically, the thickest parts of Sunda porcupines placenta consist of chorioallantoic plate, labyrinth zone, trophospongium, decidua, metrial glands, myometrium zone. In conclussion, the placenta of sunda porcupine (Hystrix javanica) has been identified which has a discoid shape and is classified to the hemochorial type. Keywords | Sunda porcupines, Placenta, Type, Histological structure Received | November 21, 2019; Accepted | February 17, 2020; Published | March 03, 2020 *Correspondence | Teguh Budipitojo, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; Email: [email protected] Citation | Budipitojo T, Shofiyah S, Masithoh DBH, Khasanah LM, Padeta I (2020). -

Evolutionary History of Carnivora (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria) Inferred

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.05.326090; this version posted October 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. It is not subject to copyright under 17 USC 105 and is also made available for use under a CC0 license. 1 Manuscript for review in PLOS One 2 3 Evolutionary history of Carnivora (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria) inferred 4 from mitochondrial genomes 5 6 Alexandre Hassanin1*, Géraldine Véron1, Anne Ropiquet2, Bettine Jansen van Vuuren3, 7 Alexis Lécu4, Steven M. Goodman5, Jibran Haider1,6,7, Trung Thanh Nguyen1 8 9 1 Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), Sorbonne Université, 10 MNHN, CNRS, EPHE, UA, Paris. 11 12 2 Department of Natural Sciences, Faculty of Science and Technology, Middlesex University, 13 United Kingdom. 14 15 3 Centre for Ecological Genomics and Wildlife Conservation, Department of Zoology, 16 University of Johannesburg, South Africa. 17 18 4 Parc zoologique de Paris, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. 19 20 5 Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA. 21 22 6 Department of Wildlife Management, Pir Mehr Ali Shah, Arid Agriculture University 23 Rawalpindi, Pakistan. 24 25 7 Forest Parks & Wildlife Department Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. 26 27 28 * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.05.326090; this version posted October 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. -

Smutsia Temminckii – Temminck's Ground Pangolin

Smutsia temminckii – Temminck’s Ground Pangolin African Pangolin Working Group and the IUCN Species Survival Commission Pangolin Specialist Group) is Temminck’s Ground Pangolin. No subspecies are recognised. Assessment Rationale The charismatic and poorly known Temminck’s Ground Pangolin, while widely distributed across the savannah regions of the assessment region, are severely threatened by electrified fences (an estimated 377–1,028 individuals electrocuted / year), local and international bushmeat and traditional medicine trades (since 2010, the number of Darren Pietersen confiscations at ports / year has increased exponentially), road collisions (an estimated 280 killed / year) and incidental mortalities in gin traps. The extent of occurrence Regional Red List status (2016) Vulnerable A4cd*†‡ has been reduced by an estimated 9–48% over 30 years National Red List status (2004) Vulnerable C1 (1985 to 2015), due to presumed local extinction from the Free State, Eastern Cape and much of southern KwaZulu- Reasons for change No change Natal provinces. However, the central interior (Free State Global Red List status (2014) Vulnerable A4d and north-eastern Eastern Cape Province) were certainly never core areas for this species and thus it is likely that TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) Vulnerable the corresponding population decline was far lower overall CITES listing (2000) Appendix II than suggested by the loss of EOO. Additionally, rural settlements have expanded by 1–9% between 2000 and Endemic No 2013, which we infer as increasing poaching pressure and *Watch-list Data †Watch-list Threat ‡Conservation Dependent electric fence construction. While throughout the rest of Africa, and Estimated mature population size ranges widely increasingly within the assessment region, local depending on estimates of area of occupancy, from 7,002 and international illegal trade for bushmeat and to 32,135 animals. -

Pangolin Genomes and the Evolution of Mammalian Scales and Immunity

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 24, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Pangolin genomes and the evolution of mammalian scales and immunity Siew Woh Choo,1,2,3,22 Mike Rayko,4,22 Tze King Tan,1,2 Ranjeev Hari,1,2 Aleksey Komissarov,4 Wei Yee Wee,1,2 Andrey A. Yurchenko,4 Sergey Kliver,4 Gaik Tamazian,4 Agostinho Antunes,5,6 Richard K. Wilson,7 Wesley C. Warren,7 Klaus-Peter Koepfli,8 Patrick Minx,7 Ksenia Krasheninnikova,4 Antoinette Kotze,9,10 Desire L. Dalton,9,10 Elaine Vermaak,9 Ian C. Paterson,2,11 Pavel Dobrynin,4 Frankie Thomas Sitam,12 Jeffrine J. Rovie-Ryan,12 Warren E. Johnson,8 Aini Mohamed Yusoff,1,2 Shu-Jin Luo,13 Kayal Vizi Karuppannan,12 Gang Fang,14 Deyou Zheng,15 Mark B. Gerstein,16,17,18 Leonard Lipovich,19,20 Stephen J. O’Brien,4,21 and Guat Jah Wong1 1Genome Informatics Research Laboratory, Centre for Research in Biotechnology for Agriculture (CEBAR), University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2Department of Oral and Craniofacial Sciences, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 3Genome Solutions Sdn Bhd, Research Management & Innovation Complex, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 4Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia 199004; 5CIIMAR/CIMAR, Interdisciplinary Centre of Marine and Environmental Research, University of Porto, 4050-123 Porto, Portugal; 6Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Porto, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal; 7McDonnell -

Records of Small Carnivores and of Medium-Sized Nocturnal Mammals on Java, Indonesia

Records of small carnivores and of medium-sized nocturnal mammals on Java, Indonesia E. J. RODE-MARGONO1*, A. VOSKAMP2, D. SPAAN1, J. K. LEHTINEN1, P. D. ROBERTS1, V. NIJMAN1 and K. A. I. NEKARIS1 Abstract Most small carnivores and nocturnal mammals in general on the Indonesian island of Java lack frequent and comprehensive dis- tribution surveys. Nocturnal surveys by direct observations from walked transects (survey effort 127 km, about 254 hours) and trap-nights) and direct sightings from Cipaganti, western Java, from two years’ research presence, yielded records of Leopard Cat Prionailurus bengalensis (121 encounters/2 sites), Javan Mongoose Herpestes javanicus (4/2), Yellow-throated Marten Mar- (1/1), Javan Ferret Badger Melogale orientalis (37/1), Banded Linsang Prionodon linsang (2/2), Binturong Arctictis binturong (3/2), Common Palm Civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus (145/10), Small Indian Civet Viverricula indica (8/1), Javan Chevrotain Tragulus javanicus (3/2), Javan Colugo Galeopterus variegatus (24/5), Spotted Giant Flying Squirrel Petaurista el- egans (2/1) and Red Giant Flying Squirrel P. petaurista (13/3), as well as of the research’s focus, Javan Slow Loris Nycticebus javanicus Small-toothed Palm Civet Arctogalidia trivirgata, Sunda Stink-badger Mydaus javanensis and Sunda Porcupine Hystrix javanica - sites. We report descriptive data on behaviour, ecology and sighting distances from human settlements. Regional population of the survey sites presented here would allow for more intensive studies of several species. Keywords: Arctogalidia trivirgataGaleopterus variegatus, Hystrix javanica, Javan Colugo, nocturnal mammals, Small-toothed Palm Civet, spotlighting, Sunda Porcupine Pengamatan hewan karnivora kecil dan mamalia nokturnal berukuran sedang di Jawa, Indonesia Abstrak Sebagian besar dari Ordo karnivora kecil dan mamalia nokturnal di Pulau Jawa, Indonesia kurang memiliki survey distribusi yang komprehensif. -

An Immunohistochemical Study on Testicular Steroidogenesis in the Sunda

Advance Publication The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science Accepted Date: 1 July 2019 J-STAGE Advance Published Date: 23 July 2019 ©2019 The Japanese Society of Veterinary Science Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. 1 Wildlife Science 2 Full paper 3 An immunohistochemical study on testicular steroidogenesis in the Sunda 4 porcupine (Hystrix javanica) 5 6 Anni NURLIANI1,2,3), Motoki SASAKI1,2)*, Teguh BUDIPITOJO4), Toshio 7 TSUBOTA5), Masatsugu SUZUKI2,6) and Nobuo KITAMURA1,2) 8 9 1)Department of Veterinary Medicine, Obihiro University of Agriculture and 10 Veterinary Medicine, Obihiro, Hokkaido 080-8555, Japan 11 2)United Graduate School of Veterinary Sciences, Gifu University, Gifu 12 501-1193, Japan 13 3)Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, 14 Lambung Mangkurat University, South Kalimantan 70714, Indonesia 15 4)Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Gadjah Mada 16 University, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia 17 5)Laboratory of Wildlife Biology and Medicine, Department of Environmental 18 Veterinary Science, Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido 19 University, Hokkaido 060-0818, Japan 20 6)Laboratory of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, Faculty of Applied Biological 21 Science, Gifu University, Gifu 501-1193, Japan 22 23 24 25 *Correspondence to: SASAKI, M., Department of Veterinary Medicine, 26 Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Obihiro, 27 Hokkaido 080-8555, Japan. e-mail: [email protected] 28 29 30 Running head: STEROIDOGENESIS IN PORCUPINE TESTES 31 32 1 33 ABSTRACT 34 In the testes of the Sunda porcupine (Hystrix javanica), the expression of the 35 steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) and steroidogenic enzymes, 36 such as cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage (P450scc), 3β-hydroxysteroid 37 dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase (P450c17) and 38 cytochrome P450 aromatase (P450arom), was immunohistochemically 39 examined to clarify the location of steroidogenesis. -

Pangolin Genomes and the Evolution of Mammalian

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 1 Pangolin genomes and the evolution of mammalian scales 2 and immunity 3 4 The International Pangolin Research Consortium (IPaRC) 5 Siew Woh Choo1,10,14*, Mike Rayko2*, Tze King Tan1,10, Ranjeev Hari1,10, Aleksey Komissarov2, Wei 6 Yee Wee1,10, Andrey Yurchenko2, Sergey Kliver2, Gaik Tamazian2, Agostinho Antunes16,17, Richard K. 7 Wilson3, Wesley C. Warren3, Klaus-Peter Koepfli15, Patrick Minx3, Ksenia Krasheninnikova2, Antoinette 8 Kotze20,21, Desire L. Dalton20,21, Elaine Vermaak20, Ian C. Paterson10,18, Pavel Dobrynin2, Frankie Thomas 9 Sitam11, Jeffrine Rovie Ryan Japning11, Warren E. Johnson15, Aini Mohamed Yusoff1,10, Shu-Jin Luo9, 10 Kayal Vizi Karuppannan11, Gang Fang19, Deyou Zheng8, Mark B. Gerstein5,6,7, Leonard Lipovich4,12, 11 Stephen J. O’Brien 2,13 and Guat Jah Wong1 12 13 1Genome Informatics Research Laboratory, High Impact Research (HIR) Building, University of Malaya, 14 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 15 2Theodosius Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, St. Petersburg State University, Russia. 16 3McDonnell Genome Institute, Washington University, St Louis, MO 63108, USA. 17 4Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48201, USA. 18 5Program in Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520, USA 19 6Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, P.O. Box 208114, Yale University, New Haven, 20 CT 06520, USA. 21 7Department of Computer Science, Yale University, Bass 432, 266 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 22 06520, USA. 23 8Department of Neurology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Ave, Bronx, NY 24 10461, USA. -

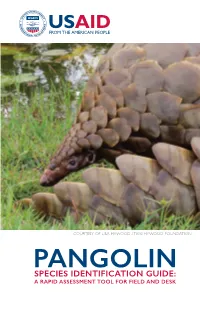

Pangolin-Id-Guide-Rast-English.Pdf

COURTESY OF LISA HYWOOD / TIKKI HYWOOD FOUNDATION PANGOLIN SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE: A RAPID ASSESSMENT TOOL FOR FIELD AND DESK Citation: Cota-Larson, R. 2017. Pangolin Species Identification Guide: A Rapid Assessment Tool for Field and Desk. Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. Bangkok: USAID Wildlife Asia Activity. Available online at: http://www.usaidwildlifeasia.org/resources. Cover: Ground Pangolin (Smutsia temminckii). Photo: Lisa Hywood/Tikki Hywood Foundation For hard copies, please contact: USAID Wildlife Asia, 208 Wireless Road, Unit 406 Lumpini, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel: +66 20155941-3, Email: [email protected] About USAID Wildlife Asia The USAID Wildlife Asia Activity works to address wildlife trafficking as a transnational crime. The project aims to reduce consumer demand for wildlife parts and products, strengthen law enforcement, enhance legal and political commitment, and support regional collaboration to reduce wildlife crime in Southeast Asia, particularly Cambodia; Laos; Thailand; Vietnam, and China. Species focus of USAID Wildlife Asia include elephant, rhinoceros, tiger, and pangolin. For more information, please visit www.usaidwildlifeasia.org Disclaimer The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ANSAR KHAN / LIFE LINE FOR NATURE SOCIETY CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 2 INTRODUCTION TO PANGOLINS 3 RANGE MAPS 4 SPECIES SUMMARIES 6 HEADS AND PROFILES 10 SCALE DISTRIBUTION 12 FEET 14 TAILS 16 SCALE SAMPLES 18 SKINS 22 PANGOLIN PRODUCTS 24 END NOTES 28 REGIONAL RESCUE CENTER CONTACT INFORMATION 29 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TECHNICAL ADVISORS: Lisa Hywood (Tikki Hywood Foundation) and Quyen Vu (Education for Nature-Vietnam) COPY EDITORS: Andrew W.