History and Technique of Odissi Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Leaf Manuscripts Inheritance of Odisha: a Historical Survey

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2019; 5(4): 77-82 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2019; 5(4): 77-82 Palm leaf manuscripts inheritance of Odisha: A © 2019 IJSR www.anantaajournal.com historical survey Received: 16-05-2019 Accepted: 18-06-2019 Dr. Jharana Rani Tripathy Dr. Jharana Rani Tripathy PDF Scholar Dept.of Sanskrit Pondicherry University, Introduction Pondicherry, India Odisha was well-known as Kalinga, Kosala, Odra and Utkala during ancient days. Altogether these independent regions came under one administrative control which was known as Utkala and subsequently Orissa. The name of Utkala has been mentioned in Mahabharata, Ramayana and Puranas. The existence of Utkala as a kingdom is found in Kalidas's Raghuvamsa. It is stated that king Raghu after having crossed the river Kapisa reached the Utkala country and finally went to Kalinga. The earliest epigraphic evidence to Utakaladesa is found from the Midnapur plate of Somdatta which includes Dandabhukti within its jurisdiction1. The plates record that while Sasanka was ruling the earth, his feudatory Maharaja Somadatta was governing the province of Dandabhukti adjoining the Utkala-desa. The Kelga plate 8 indicate s that Udyotakesari's son and successors of Yayati ruled about the 3rd quarter of eleventh century, made over Kosala to prince named Abhimanyu and was himself ruling over Utkala After the down-fall of the Matharas in Kalinga, the Gangas held the reines of administration in or about 626-7 A, D. They ruled for a long period of about five hundred years, when, at last,they extended their power as far as the Gafiga by sujugating Utkala in or about 1112 A. -

Fashioning Readers: Canon, Criticism and Pedagogy in the Emergence of Modern Oriya Literature

1 Fashioning Readers: Canon, Criticism and Pedagogy in the Emergence of Modern Oriya Literature Pritipuspa Mishra University of Southampton Postal Address: University of Southampton Avenue Campus Highfield Southampton SO17 1BF UK Email- [email protected] This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Contemporary South Asia on 22nd March 2012, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2011.646080 Abstract Through a brief history of a widely published canon debate in nineteenth century Orissa, this paper describes how anxieties about the quality of “traditional” Oriya literature served as a site for imagining a cohesive Oriya public who would become the consumers and beneficiaries of a new, modernized Oriya-language canon. A public controversy about the status of Oriya literature was initiated in the 1890s with the publication of a serialized critique of the works of Upendra Bhanja, a very popular pre-colonial Oriya poet. The critic argued that Bhanja’s writing was not true poetry, that it did not speak to the contemporary era, and that it featured embarrassingly detailed discussions of obscene material. By unpacking the terms of this criticism and Oriya responses to it, I reveal how at the heart of these discussions were concerns about community building that presupposed a new kind of readership of literature in the Oriya language. Ultimately, this paper offers a longer, regional history to the emerging concern of post-colonial scholarship with relationships between publication histories, readerships, and broader ideas of community—local, Indian and global. Key words Literary Criticism, Oriya literature, Tradition, Public Word Count: 7344 including references 2 In the winter of 1891, in the capital of the princely state of Majurbhanj set deep in the hills of the Eastern Ghats, a series of articles critiquing the work of an early modern Oriya poet were published. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 8 MARCH - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Sri Krsna - Jagannath Consciousness : Vyasa - Jayadeva - Sarala Dasa Dr. Satyabrata Das ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty ... 4 Language and Language Policy in India Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Rise of the Odia Novel : 1897-1930 Jitendra Narayan Patnaik ... 18 Gangadhar Literature : A Bird’s Eye View Jagabandhu Panda ... 23 Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath ... 25 The Evolution of Odia Language : An Introspection Dr. Jyotirmati Samantaray ... 29 Biju - The Greatest Odia in Living Memory Rajkishore Mishra ... 31 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 34 Role of Maharaja Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo in the Odia Language Movement Harapriya Das Swain ... 38 Odissi Vocal : A Unique Classical School Kirtan Narayan Parhi .. -

Odisha Sahitya Academy Awarded Books and Writers

ODISHA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2011 ODISHA SAHITYA ACADEMY AWARDED BOOKS AND WRITERS Sl. Name of the Book Category Name of Writers No. 1957-1958 1. Dilip Lyric Poem Sri Upendra Mohanty 2. Swarna Yugara Sandhana Play Sri Gyaneendra Burma 3. Agnee Parikshya Play Shri Bhanjakishore Patnaik 4. Vyasakabi Fakir Mohan Criticism Shri Natabar Samantaray 5. Veda Manushya Kruta Ki ? Criticism Shri Priyabrata Das 6. Godan Translation Golakha Bihari Dhal 7. Ajara Pound Kabita Translation Shri Gyaneendra Burma 8. Sabujapatra O Dhusara Golap Story Shri Surendra Mohanty 9. Chora Chaitali Story Smt. Rajeswari Dalbehera 10. Kanta O Phula Poetry Shri Godabarish Mohapatra 11. Sanchayan Poetry Smt. Bidyutprabha Devi 12. Bhagaban Sankaracharya Biography Shri Durga Charan Mohanty 13. Jateeya Jeebanara Atmabikash Biography Shri Gobinda Chandra Mishra 14. Odishi Chitra Science Literature Shri Binod Routray 15. Puspa Chasha Science Literature Shri Biswanath Sahoo 16. Kalinga Kahani Child Literature Smt. Kanaka Manjari Mohapatra 17. Pilanka Katha Lahari Child Literature Shri Chandra Sekhar Mohapatra 18. Europere Mo Anubhuti Travel Story Sriram Chandra Das 1959-1961 19. Aranyak Story Shri Manoj Das 20. Ootha Kankal Poetry Late Godabarish Mohapatra 21. Pashchima Diganta Travel Story Shri Shriharsha Mishra 22. E Jugara Shrestha Abiskar Science Literature Shri Gokulananda Mohapatra 23. Jeeban Bidyalaya Essay Shri Chittaranjan Das 24. Juga Prabarttak Radhanath Criticism Shri Natabar Samantaray 25. Kabi Samrat Upendra Bhanja Criticism Shri Ananta Padmanav Patnaik 26. Charam Patra Poetry Shri Rabindra Nath Singh 27. Nar Kinnar Novel Shri Shantanu Ku.Acharya 1962-1964 28. Adi Manabara Itibrutta Story Shri Kamal Lochan Baral 29. Satyabhama Lyric Poem Shri Golak Chandra Pradhan 30. -

Ati 3M: Odissi Dance

BLM #1 STUDENT/TEACHER RESOURCE ATI 3M: ODISSI DANCE Odissi dance is the typical classical dance form of Orissa and has its origin in the temples. The rhythm, the bhangis and mudras used in Odissi dance have a distinctive quality of their own. Odissi dance deals largely with the love theme of Radha and Krishna. It is a lyrical form of dance with its subtlety as its keynote. The intimate relationship experienced between the poetry and music in Odissi is a feature on which the aesthetics of the style is built. It is a "sculpturesque" style of dance with a harmony of line and movement, all its own. The history of Odissi dates back to somewhere between the 8th and the 11th century when the kings took great pride in excelling in the arts of dance and music. It is during these centuries that inscriptions referring to "Devdasis,” the women who worshipped the deity, were carved at the Brahmeshwar temple. "Devdasis" apparently played an important part in the temple ritual and were required to perform from early evening to the bedtime of Lord Jagannath, the temple deity of Puri. Jayadeva's "Geeta-Govinda,” the bible of an Odissi dancer, written in the 12th century, has stupendous influence on the arts of Orissa. The "Ashtapadis" were marked with specific ragas and talas. Around the 15th century, during the reign of Surya Dynasty, the element of "abhinaya" or expressional dance entered Odissi. During the same time Maheshwar Mahapatra wrote his "Abhinaya Chandrika,” an elaborate treatise on Odissi dance style, which is still used by dancers today. -

4.2.5 Saivism 90 Xn

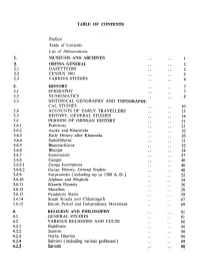

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Table of Contents List of Abbreviations 1. MUSEUMS AND ARCHIVES 2. ORISSA, GENERAL 2 2.1 GAZETTEERS 2 2.2 CENSUS 1961 3 2.3 VARIOUS STUDIES 4 3. HISTORY 7 3.1 EPIGRAPHY 7 3.2 NUMISMATICS 8 3.3 HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY AND TOPOGRAPHI- CAL STUDIES 10 3.4 ACCOUNTS OF EARLY TRAVELLERS 13 3.5 HISTORY, GENERAL STUDIES 14 3.6 PERIODS OF ORISSAN HISTORY 21 3.6.1 Prehistory 21 3.6.2 Asoka and Kharavela 22 3.6.3 Early History after Kharavela 26 3.6.4 Sailodbhavas 31 3.6.5 Bhauma-Karas 32 3.6.6 Bhanjas 34 3.6.7 Somavamsis 37 3.6.8 Gangas 40 3.6.8.1 Ganga Inscriptions 40 3.6.8.2 Ganga History, General Studies 48 3.6.9 Suryavamsis (including up to 1568 A. D.) 52 3.6.10 Afghans and Moghuls 54 3.6.11 Khurda Dynasty 56 3.6.12 Marathas 58 3.6.13 Feudatory States 59 3.6.14 South Kosala and Chhattisgarh 67 3.6.15 British Period and Independence Movement 69 4. RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY 81 4.1 GENERAL STUDIES 81 4.2 VARIOUS RELIGIONS AND CULTS 86 4.2.1 Buddhism 86 4.2.2 Jainism 4.2.3 Natha Dharma 4.2.4 Saktism (including various goddesses) 89 4.2.5 Saivism 90 xn 4.2.6 Surya Cult 91 4.2.7 Vaisnavism 92 4.2.8 Jagannatha Cult 94 4.2.9 Mahima Dharma 103 5. ART 104 5.1 GENERAL STUDIES 104 5.2 ARCHAEOLOGY ( Excavations ) 107 5.3 MONUMENTS, ARCHITECTURE 110 5.4 PLASTIC ART AND ICONOGRAPHY 118 5.5 PAINTING 122 5.6 INDUSTRIAL ART AND APPLIED ART 123 5.7 FOLK ART 124 5.8 DANCE AND MUSIC 125 6. -

Odissi Dance) 2020 THREE YEAR FULL TIME PROGRAMME

Learning Outcome based Curriculum Framework (LOCF) For Undergraduate Programme B.P.A. (Odissi Dance) 2020 THREE YEAR FULL TIME PROGRAMME Syllabus and Scheme of Examination This shall be applicable for students seeking admission in B.P.A. Odissi Dance Programme in 2020-2021 DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS Faculty of Indic Studies Sri Sri University DPA-B.P.A. (O.D.) Page 0 Introduction – The proposed programme shall be conducted and supervised by the Faculty of Indic Studies, Department of Performing Arts, Sri Sri University, Cuttack (Odisha). This programme has been designed on the Learning Outcomes Curriculum Framework (LOCF) under UGC guidelines, offers flexibility within the structure of the programme while ensuring the strong foundation and in-depth knowledge of the discipline. The learning outcome-based curriculum ensures its suitability in the present day needs of the student towards higher education and employment. The Department of Performing Arts at Sri Sri University is now offering bachelor degree program with specialization in Performing Arts (Odissi Dance and Hindustani Vocal Music) Vision – The Department of Performing Arts aims to impart holistic education to equip future artistes to achieve the highest levels of professional ability, in a learning atmosphere that fosters universal human values through the Performing Arts. To preserve, perpetuate and monumentalize through the Guru-Sishya Parampara (teacher-disciple tradition) the classical performing arts in their essence of beauty, harmony and spiritual evolution, giving scope for innovation and continuity with change to suit modern ethos. Mission : To be a center of excellence in performing arts by harnessing puritan skills from Vedic days to modern times and creating artistic expressions through learned human ingenuity of emerging times for furtherance of societal interest in the visual & performing arts. -

Eminent Literary Luminaries of Orissa

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2004 EMINENT LITERARY LUMINARIES OF ORISSA JAYADEVA Jayadeva lived in the twelfth century and is well-known author of the musical epic Sri Geeta Govinda. He hailed from Kenduli village in the Prachi Valley between Bhubaneswar and Puri. He spent most of his life at Puri and composed the songs of Sri Geeta Govinda as musical offerings to Lord Jagannath. Padmavati his beloved wife, danced to the songs sang and choreographed by Jayadeva. The composition was probably performed first on the twin occasions of the dedication on the Srimandir and the coronation of Kamarnava as the crown prince in 1142 AD, during the reign of Chodaganga Deva, the founder of the great Ganga Empire in the east coast of India, Jayadeva, a great scholar and composer was a devotee first and a poet next. His Sri Geeta Govinda is a glorification of the essence of Jagannath Chetana or Jagannath Consciousness–the path of simple surrender, which later Sri Chaitanya popularized as the Gopi Bhava or the Radha Bhava. Gitagovinda has become the main prop of Odissi dance. It also has an enormous influence on the patta paintings of Raghurajpur. As a beautiful, ornate kavya, Gitagovinda received appreciation at home and abroad. Its sonorous diction and rhythmic musical excellence have created a unique place for it in world literature. Gitagovinda consists of twelve cantos or sargas including twenty- four songs and seventy- two slokas. It is designed to be sung in definite ragas and talas. It has been rightly observed that a narrative thread runs through the songs, lending it a dramatic structure. -

1481008958P5M11TEXT.Pdf

PAPER 5 DANCE, POETS AND POETRY, RELIGIOUS PHILOSOPHY AND INDIAN CLASSICAL DANCE MODULE 11 SAHITYA, KAVYA AND GEETA OF ODISSI All the fine arts are interdependent & to each other. Sometimes they are segregated to concentrate on their individual growth & enhance their richness. But they evolve collectively. Music, Drama, Dance & Literature are inseparable & interdependent. Most of the dance treatise classified dance in three categories: Natya, Nritta & Nritya. Nritta is the dance which is always embellished with ornamental had gestures & postures with supportive music without a song. Nritya is expressional dance and performed to convey the meaning of a theme through codified meaningful hand gestures (Mudra), suggestive facial expression (Bhava / भाव) & symbolic poses (Bhangi / भॊगी). Natya is predominated by the elements of drama such as dialogues or spoken words in addition to the Nritya & Nritta in it. Both Nritya / न्रित्य & Natya / ना絍य are dependent on Vachika / वाचिक & Aharya / आहायय Abhinaya / अभभनय and expresses itself through Angika / अॊचगका & Swatika Abhinaya / सात्त्वक अभभनय. The importance of Vachika abhinaya is understandably lot more than other three abhinayas. Words with proper punctuations & modulation reach the spectators in no time. Sometime even if they don’t see the characters they follow the story hearing, the dialogues only. It is said Vachika Abhinaya is the king & other abhinayas follow 1 it. The accompanying song (geeta / गीत) can be considered as Bachika Abhinaya in dance. Dance follows Vadya, But Vadya Follows Geeta. Nrittang Badyanung Proktang Badyang Geetanubarticha न्रितॊग ब饍यानुॊग प्रोक्तॊग गीतानुबन्रतिय ा- Sangeet Ratnakar Tasya Geetasya Mahatmya ke Prasangsitumishate तस्य गीतस्य महात््य के प्रसॊगभसतुभमशते Dharmarthya KamaMoskhyana midamebaik sadhanam धमयर्थयय काम मोक्ष्याना भमदामेबैक साधनॊ – Sangeet Ratnakar It is not easy to describe the magnitude of songs. -

The Debaprasad Das Tradition: Reconsidering the Narrative of Classical Indian Odissi Dance History Paromita Kar a Dissertation S

THE DEBAPRASAD DAS TRADITION: RECONSIDERING THE NARRATIVE OF CLASSICAL INDIAN ODISSI DANCE HISTORY PAROMITA KAR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO DECEMBER 2013 @PAROMITA KAR, 2013 ii Abstract This dissertation is dedicated to theorizing the Debaprasad Das stylistic lineage of Indian classical Odissi dance. Odissi is one of the seven classical Indian dance forms recognized by the Indian government. Each of these dance forms underwent a twentieth century “revival” whereby it was codified and recontextualized from pre-existing ritualistic and popular movement practices to a performance art form suitable for the proscenium stage. The 1950s revival of Odissi dance in India ultimately led to four stylistic lineage branches of Odissi, each named after the corresponding founding pioneer of the tradition. I argue that the theorization of a dance lineage should be inclusive of the history of the lineage, its stylistic vestiges and philosophies as embodied through its aesthetic characteristics, as well as its interpretation, and transmission by present-day practitioners. In my theorization of the Debaprasad Das lineage of Odissi, I draw upon Pierre Bourdieu's theory of the habitus, and argue that Guru Debaprasad Das's vision of Odissi dance was informed by the socio-political backdrop of Oriya nationalism, in the context of which he choreographed, but also resisted the heavy emphasis on coastal Oriya culture of the Oriya nationalist movement. My methodology for the project has been ethnographic, supported by original archival research. -

Music and Dance Tradition of Odisha - Quest for Odia Identity

December - 2014 Odisha Review Music And Dance Tradition of Odisha - Quest for Odia Identity Indu Bhusan Kar Odisha is a divine land of art, architecture and music and dance of Odisha made him the most religion. The land is also known as land of synthetic popular ruler of Kalinga. He constructed nearly culture, where Lord Shree Jagannath, the Lord 117 caves at Khandagiri and Udayagiri with of Universe is worshipped, Jagannath cult artistic sculptural excellence. preaches equality, fraternity and peace, It is worthwhile to know the origin and irrespective of caste, creed and religion. The evolution of ancient musical tradition of Odisha artistic sensibility of Odias has been well reflected with an object of shaping the continuous in art and architectures of world famous temple enrichment of Odishan music. In this context it is at Konark, Rajarani at Bhubaneswar, Shree necessary to know what has been written in this Jagannath of Puri, Lingaraj at Bhubaneswar and Hatigumpha inscription regarding this Gandharva of many monuments and rock, caves. The artists art ? The fifth line of Hatigumpha inscription reads of Odisha not only excelled in architecture, but as follows. also in performing arts. The musical tradition of Odisha had a glorious past, dating back from 1st “Expert in Gandharva Veda Kharavela Century B.C. where the emperor Kharavela ruled arranged for entertainment of his subjects, the Kalinga whose territorial boundary was spread musical items such as DAPA (combat), from Ganga to Godavari river in south. The NATA(dance) GITA (music), VADITA documentary evidence of Odishan ancient musical (orchestra), USABA (festival), SAMAJA (Play tradition has been discovered and deciphered in or dramas, SAMAJ Jatra)”. -

Poetry As Performance

Poetry as Performance (The Origin and Development of Pa/a in Orissa) Sitakant Mahapatra Pala occupies a very special place in the complex mosaic of Orissa's performing arts. It shares certain elements with the other forms of folk performing arts such as Jatra, Suanga and Lee/a. Like them Pa/a uses literary themes, stories and anecdotes to entertain spectators. Like these forms, it. too, is a blend of story-telling through kavya, music and dramatic performance designed to grip the imagination of the audience. But. in addition, Pala is intimately linked, on the one hand, to a form of religious worship and ritual practised in medieval Orissa and, on the other, to the elitist culture of the pundits and scholars well-versed in the Sanskritic tradition of the Purana-s and other literary works. 2 The worship of Pancha devata (the t1ve deities) can be traced to a very old tradition in Orissa. The deities are Ganesha, Vishnu, Durga, Shiva and Bhaskara (the Sun-god). During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. at the time of the Bhaumakara, Somavamsi and Ganga dynastic rule in Orissa, the relative importance of Shaiva, Shakta and Vaishnava cults and forms of worship kept on fluctuating on the basis of royal patronage. The Somavamsis were patrons of Shiva worship and the Bhaumakaras of Shakti worship. While they patronised Vaishnavite worship, the Gangas were not averse to Shaiva or Shakta cults. Later, during the period of the Gangas, to these three was added the worship of Bhaskara and Ganesha. In fact. particular kshetra-s or places of worship came to be associated with each of these presiding deities.