The Magellanic Clouds, Past, Present and Future-A Summary of IAU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portrait of a Dramatic Stellar Crib 21 December 2006

Portrait of a dramatic stellar crib 21 December 2006 most massive stars known. The nebula owes its name to the arrangement of its brightest patches of nebulosity, that somewhat resemble the legs of a spider. They extend from a central 'body' where a cluster of hot stars (designated 'R136') illuminates and shapes the nebula. This name, of the biggest spiders on the Earth, is also very fitting in view of the gigantic proportions of the celestial nebula - it measures nearly 1,000 light-years across and extends over more than one third of a degree: almost, but not quite, the size of the full Moon. If it were in our own Galaxy, at the distance of another stellar nursery, the Orion Nebula (1,500 light-years away), it would cover one quarter of the sky and even be visible in daylight. One square degree image of the Tarantula Nebula and its surroundings. The spidery nebula is seen in the upper- center of the image. Slightly to the lower-right, a web of filaments harbors the famous supernova SN 1987A (see below). Many other reddish nebulae are visible in the image, as well as a cluster of young stars on the left, known as NGC 2100. Credit: ESO Known as the Tarantula Nebula for its spidery appearance, the 30 Doradus complex is a monstrous stellar factory. It is the largest emission nebula in the sky, and can be seen far down in the southern sky at a distance of about 170,000 light- years, in the southern constellation Dorado (The Swordfish or the Goldfish). -

The Role of Evolutionary Age and Metallicity in the Formation of Classical Be Circumstellar Disks 11

< * - - *" , , Source of Acquisition NASA Goddard Space Flight Center THE ROLE OF EVOLUTIONARY AGE AND METALLICITY IN THE FORMATION OF CLASSICAL BE CIRCUMSTELLAR DISKS 11. ASSESSING THE TRUE NATURE OF CANDIDATE DISK SYSTEMS J.P. WISNIEWSKI"~'~,K.S. BJORKMAN~'~,A.M. MAGALH~ES~",J.E. BJORKMAN~,M.R. MEADE~, & ANTONIOPEREYRA' Draft version November 27, 2006 ABSTRACT Photometric 2-color diagram (2-CD) surveys of young cluster populations have been used to identify populations of B-type stars exhibiting excess Ha emission. The prevalence of these excess emitters, assumed to be "Be stars". has led to the establishment of links between the onset of disk formation in classical Be stars and cluster age and/or metallicity. We have obtained imaging polarization observations of six SMC and six LMC clusters whose candidate Be populations had been previously identified via 2-CDs. The interstellar polarization (ISP). associated with these data has been identified to facilitate an examination of the circumstellar environments of these candidate Be stars via their intrinsic ~olarization signatures, hence determine the true nature of these objects. We determined that the ISP associated with the SMC cluster NGC 330 was characterized by a modified Serkowski law with a A,,, of -4500A, indicating the presence of smaller than average dust grains. The morphology of the ISP associated with the LMC cluster NGC 2100 suggests that its interstellar environment is characterized by a complex magnetic field. Our intrinsic polarization results confirm the suggestion of Wisniewski et al. that a substantial number of bona-fide classical Be stars are present in clusters of age 5-8 Myr. -

Download the 2016 Spring Deep-Sky Challenge

Deep-sky Challenge 2016 Spring Southern Star Party Explore the Local Group Bonnievale, South Africa Hello! And thanks for taking up the challenge at this SSP! The theme for this Challenge is Galaxies of the Local Group. I’ve written up some notes about galaxies & galaxy clusters (pp 3 & 4 of this document). Johan Brink Peter Harvey Late-October is prime time for galaxy viewing, and you’ll be exploring the James Smith best the sky has to offer. All the objects are visible in binoculars, just make sure you’re properly dark adapted to get the best view. Galaxy viewing starts right after sunset, when the centre of our own Milky Way is visible low in the west. The edge of our spiral disk is draped along the horizon, from Carina in the south to Cygnus in the north. As the night progresses the action turns north- and east-ward as Orion rises, drawing the Milky Way up with it. Before daybreak, the Milky Way spans from Perseus and Auriga in the north to Crux in the South. Meanwhile, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds are in pole position for observing. The SMC is perfectly placed at the start of the evening (it culminates at 21:00 on November 30), while the LMC rises throughout the course of the night. Many hundreds of deep-sky objects are on display in the two Clouds, so come prepared! Soon after nightfall, the rich galactic fields of Sculptor and Grus are in view. Gems like Caroline’s Galaxy (NGC 253), the Black-Bottomed Galaxy (NGC 247), the Sculptor Pinwheel (NGC 300), and the String of Pearls (NGC 55) are keen to be viewed. -

Optical Astronomy Observatories

NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORIES NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORIES FY 1994 PROVISIONAL PROGRAM PLAN June 25, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND PLAN OVERVIEW 1 II. SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM 3 A. Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory 3 B. Kitt Peak National Observatory 9 C. National Solar Observatory 16 III. US Gemini Project Office 22 IV. MAJOR PROJECTS 23 A. Global Oscillation Network Group (GONG) 23 B. 3.5-m Mirror Project 25 C. WIYN 26 D. SOAR 27 E. Other Telescopes at CTIO 28 V. INSTRUMENTATION 29 A. Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory 29 B. Kitt Peak National Observatory 31 1. KPNO O/UV 31 2. KPNO Infrared 34 C. National Solar Observatory 38 1. Sacramento Peak 38 2. Kitt Peak 40 D. Central Computer Services 44 VI. TELESCOPE OPERATIONS AND USER SUPPORT 45 A. Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory 45 B. Kitt Peak National Observatory 45 C. National Solar Observatory 46 VII. OPERATIONS AND FACILITIES MAINTENANCE 46 A. Cerro Tololo 47 B. Kitt Peak 48 C. NSO/Sacramento Peak 48 D. NOAO Tucson Headquarters 49 VIII. SCIENTIFIC STAFF AND SUPPORT 50 A. CTIO 50 B. KPNO 50 C. NSO 51 IX. PROGRAM SUPPORT 51 A. NOAO Director's Office 51 B. Central Administrative Services 52 C. Central Computer Services 52 D. Central Facilities Operations 53 E. Engineering and Technical Services 53 F. Publications and Information Resources 53 X. RESEARCH EXPERIENCES FOR UNDERGRADUATES PROGRAM 54 XI. BUDGET 55 A. Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory 56 B. Kitt Peak National Observatory 56 C. National Solar Observatory 57 D. Global Oscillation Network Group 58 E. -

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and Astrophysical Phenomena Therein

THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to the Magellanic Clouds, and astrophysical phenomena therein No. 146 — 4 April 2017 http://www.astro.keele.ac.uk/MCnews Editor: Jacco van Loon Figure 1: The remarkable change in spectral of the Luminous Blue Variable R 71 in the LMC during its current major and long-lasting eruption, from B-type to G0. Even more surprising is the appearance of prominent He ii emission before the eruption, totally at odds with its spectral type at the time. Explore more spectra of this and other LBVs in Walborn et al. (2017). 1 Editorial Dear Colleagues, It is my pleasure to present you the 146th issue of the Magellanic Clouds Newsletter. Besides an unusually large abundance of papers on X-ray binaries and massive stars you may be interested in the surprising claim of young stellar objects in mature clusters, while a massive intermediate-age cluster in the SMC shows no evidence for multiple populations. Marvel at the superb image of R 136 and another paper suggesting a scenario for its formation involving gas accreted from the SMC – adding evidence for such interaction to other indications found over the past twelve years. Congratulations with the quarter-centennial birthday of OGLE! They are going to celebrate it, and you are all invited – see the announcement. Further meetings will take place in Heraklion (Be-star X-ray binaries) and Hull (Magellanic Clouds), and again in Poland (RR Lyræ). The Southern African Large Telescope and the South African astronomical community are looking for an inspiring, ambitious and world-leading candidate for the position of SALT chair at a South African university of your choice – please consider the advertisement for this tremendous opportunity. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

Astronomy Magazine 2012 Index Subject Index

Astronomy Magazine 2012 Index Subject Index A AAR (Adirondack Astronomy Retreat), 2:60 AAS (American Astronomical Society), 5:17 Abell 21 (Medusa Nebula; Sharpless 2-274; PK 205+14), 10:62 Abell 33 (planetary nebula), 10:23 Abell 61 (planetary nebula), 8:72 Abell 81 (IC 1454) (planetary nebula), 12:54 Abell 222 (galaxy cluster), 11:18 Abell 223 (galaxy cluster), 11:18 Abell 520 (galaxy cluster), 10:52 ACT-CL J0102-4915 (El Gordo) (galaxy cluster), 10:33 Adirondack Astronomy Retreat (AAR), 2:60 AF (Astronomy Foundation), 1:14 AKARI infrared observatory, 3:17 The Albuquerque Astronomical Society (TAAS), 6:21 Algol (Beta Persei) (variable star), 11:14 ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array), 2:13, 5:22 Alpha Aquilae (Altair) (star), 8:58–59 Alpha Centauri (star system), possibility of manned travel to, 7:22–27 Alpha Cygni (Deneb) (star), 8:58–59 Alpha Lyrae (Vega) (star), 8:58–59 Alpha Virginis (Spica) (star), 12:71 Altair (Alpha Aquilae) (star), 8:58–59 amateur astronomy clubs, 1:14 websites to create observing charts, 3:61–63 American Astronomical Society (AAS), 5:17 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) aging Sun-like stars in, 5:22 black hole in, 6:17 close pass by Triangulum Galaxy, 10:15 collision with Milky Way, 5:47 dwarf galaxies orbiting, 3:20 Antennae (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039) (colliding galaxies), 10:46 antihydrogen, 7:18 antimatter, energy produced when matter collides with, 3:51 Apollo missions, images taken of landing sites, 1:19 Aristarchus Crater (feature on Moon), 10:60–61 Armstrong, Neil, 12:18 arsenic, found in old star, 9:15 -

Florian Niederhofer1,2 Michael Hilker1 Nate Bastian3 Esteban Silva-Villa4,5

Florian Niederhofer1,2 Michael Hilker1 Nate Bastian3 Esteban Silva-Villa4,5 1- European Southern Observatory 2- Universitäts-Sternwarte München 3- John Moores University Liverpool 4- CRAQ 5- Universidad de Antioquia NGC 2100 Credit: ESO Searching for Age Spreads ! Color-magnitude diagrams of intermediate age (1-2 Gyr) massive clusters in the LMC show extended or double main sequence turn-offs (MSTO) NGC 1783, NGC 1806 and NGC 1846 (Mackey et al. 2008) ! If these features are related to an age spread of 200-500 Myr, young clusters (<1 Gyr) with similar properties should have age spreads of the same order, as well ! We searched for age spreads in a sample of eight young (< 1.1 Gyr) 4 massive (> 10 M") LMC clusters ! The data set consists of archival HST WFPC2 data from Brocato et al. 2001, Fischer et al. 1998 and the Hubble Legacy Archive RASPUTIN Workshop 13.-17. October 2014 Our Cluster Sample ! The selected clusters cover the age range from 20 Myr to ≈ 1 Gyr ! They follow the same mass-effective radius relation as the intermediate age clusters that show an extended MSTO ! Blue circles: Clusters analyzed in this study ! Blue dots surrounded by circles: Clusters already analyzed by Bastian & Silva-Villa 2013 ! Red triangles: Intermediate age (1-2 Gyr) clusters that show extended or double MS turn- offs (Goudfrooij 2009,11a) ! Black dots: Other LMC clusters RASPUTIN Workshop 13.-17. October 2014 CMDs of the Clusters NGC 2249 NGC 1831 NGC 2136 NGC 2157 NGC 1850 NGC 1847 Stars that are used for NGC 2004 NGC 2100 further analysis Red crosses: Stars that are removed as field stars Niederhofer et al. -

Chemical Evolution of the Large Magellanic Cloud)

EVOLUCIÓN QUÍMICA DE LA NUBE GRANDE DE MAGALLANES. (CHEMICAL EVOLUTION OF THE LARGE MAGELLANIC CLOUD) Profesor Guía: Dr. Douglas Geisler Tesis para optar al grado académico de Doctor en Ciencias Físicas Autor RENEÉ CECILIA MATELUNA PÉREZ CONCEPCIÓN - CHILE NOVIEMBRE 2012 Director de Tesis : Dr. Douglas Geisler Departamento de Astronomia, Universidad de Concepción, Chile. Comisión Evaluadora : Dr. Giovanni Carraro. European Southern Observatory, Santiago, Chile. Dipartimento di Astronomia, Universitá di Padova, Padova, Italia. Dr. Sandro Villanova. Departamento de Astronomia, Universidad de Concepción, Chile. Dr. Tom Richtler. Departamento de Astronomia, Universidad de Concepción, Chile. Dedicado a Mi Padre Agradecimientos He llegado al final de un ciclo, y son muchas las personas que me han acompañado de alguna u otra forma en este proceso. Por esta razón, es que decidí hacer estos agradecimientos en un orden más o menos cronológico. Comenzaré por mis padres: Cecilia y René, ya que gracias a ellos estoy aquí. Mamá has sido un gran apoyo en este camino, te agradezco cada gesto de amor y cada sabio consejo que me has dado. Papá, aunque no estas físicamente presente para presenciar este momento, agradezco la oportunidad que me diste para ser fuerte y seguir adelante con mis sueños a pesar de las dificultades y se que estarías muy orgulloso de mi. Muchas gracias papá por el legado que me dejaste, mis hermanos: Alejandra, Gabriel, Mariela, José Luis y Alfredo, con ellos aprendo cada día de que en la diversidad esta la belleza y la armonía, muchas gracias, son un gran apoyo, los amo. A mis tios y primos: tia Quelita, tio Rene, Dany, Pauta y a mi comadre(Cecilia), gracias por entregarme su amor, sus consejos y esos momentos de celebración y risas. -

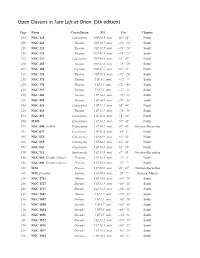

Open Clusters PAGING

Open Clusters in Turn Left at Orion (5th edition) Page Name Constellation RA Dec Chapter 193 NGC 129 Cassiopeia 0 H 29.8 min. 60° 14' North 210 NGC 220 Tucana 0 H 40.5 min. −73° 24' South 210 NGC 222 Tucana 0 H 40.7 min. −73° 23' South 210 NGC 231 Tucana 0 H 41.1 min. −73° 21' South 192 NGC 225 Cassiopeia 0 H 43.4 min. 61° 47' North 210 NGC 265 Tucana 0 H 47.2 min. −73° 29' South 202 NGC 188 Cepheus 0 H 47.5 min. 85° 15' North 210 NGC 330 Tucana 0 H 56.3 min. −72° 28' South 210 NGC 371 Tucana 1 H 3.4 min. −72° 4' South 210 NGC 376 Tucana 1 H 3.9 min. −72° 49' South 210 NGC 395 Tucana 1 H 5.1 min. −72° 0' South 210 NGC 460 Tucana 1 H 14.6 min. −73° 17' South 210 NGC 458 Tucana 1 H 14.9 min. −71° 33' South 193 NGC 436 Cassiopeia 1 H 15.5 min. 58° 49' North 210 NGC 465 Tucana 1 H 15.7 min. −73° 19' South 193 NGC 457 Cassiopeia 1 H 19.0 min. 58° 20' North 194 M103 Cassiopeia 1 H 33.2 min. 60° 42' North 179 NGC 604, in M33 Triangulum 1 H 34.5 min. 30° 47' October–December 195 NGC 637 Cassiopeia 1 H 41.8 min. 64° 2' North 195 NGC 654 Cassiopeia 1 H 43.9 min. 61° 54' North 195 NGC 659 Cassiopeia 1 H 44.2 min. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School Constraining the Evolution of Massive StarsMojgan Aghakhanloo Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES CONSTRAINING THE EVOLUTION OF MASSIVE STARS By MOJGAN AGHAKHANLOO A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Physics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Copyright © 2020 Mojgan Aghakhanloo. All Rights Reserved. Mojgan Aghakhanloo defended this dissertation on April 6, 2020. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jeremiah Murphy Professor Directing Dissertation Munir Humayun University Representative Kevin Huffenberger Committee Member Eric Hsiao Committee Member Harrison Prosper Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I dedicate this thesis to my parents for their love and encouragement. I would not have made it this far without you. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Jeremiah Murphy. I could not go through this journey without your endless support and guidance. I am very grateful for your scientific advice and knowledge and many insightful discussions that we had during these past six years. Thank you for making such a positive impact on my life. I would like to thank my PhD committee members, Professors Eric Hsiao, Kevin Huf- fenberger, Munir Humayun and Harrison Prosper. I will always cherish your guidance, encouragement and support. I would also like to thank all of my collaborators. -

Near-Infrared Polarization Source Catalog of The

The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 222:2 (13pp), 2016 January doi:10.3847/0067-0049/222/1/2 © 2016. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. NEAR-INFRARED POLARIZATION SOURCE CATALOG OF THE NORTHEASTERN REGIONS OF THE LARGE MAGELLANIC CLOUD Jaeyeong Kim1, Woong-Seob Jeong2,3, Soojong Pak1, Won-Kee Park2, and Motohide Tamura4 1 School of Space Research, Kyung Hee University, 1 Seocheon-dong, Giheung-gu, Yongin, Gyeonggi-do 446-701, Korea; [email protected] 2 Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, 776 Daedeok-daero, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305-348, Korea; [email protected] 3 Korea University of Science and Technology, 217 Gajeong-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 305-350, Korea 4 The University of Tokyo/National Astronomical Observatory of Japan/Astrobiology Center, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan Received 2015 July 1; accepted 2015 November 15; published 2016 January 8 ABSTRACT We present a near-infrared band-merged photometric and polarimetric catalog for the 39′ × 69′ fields in the northeastern part of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), which were observed using SIRPOL, an imaging polarimeter of the InfraRed Survey Facility. This catalog lists 1858 sources brighter than 14 mag in the H band with a polarization signal-to-noise ratio greater than three in the J, H,orKs bands. Based on the relationship between the extinction and the polarization degree, we argue that the polarization mostly arises from dichroic extinctions caused by local interstellar dust in the LMC. This catalog allows us to map polarization structures to examine the global geometry of the local magnetic field, and to show a statistical analysis of the polarization of each field to understand its polarization properties.