The Boundaries Between Us This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Boundaries Between Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithfield Review, Volume 20, 2016

In this issue — On 2 January 1869, Olin and Preston Institute officially became Preston and Olin Institute when Judge Robert M. Hudson of the 14th Circuit Court issued a charter Includes Ten Year Index for the school, designating the new name and giving it “collegiate powers.” — page 1 The On June 12, 1919, the VPI Board of Visitors unanimously elected Julian A. Burruss to succeed Joseph D. Eggleston as president of the Blacksburg, Virginia Smithfield Review institution. As Burruss began his tenure, veterans were returning from World War I, and America had begun to move toward a post-war world. Federal programs Studies in the history of the region west of the Blue Ridge for veterans gained wide support. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women Volume 20, 2016 suffrage, gained ratification. — page 27 A Note from the Editors ........................................................................v According to Virginia Tech historian Duncan Lyle Kinnear, “he [Conrad] seemed Olin and Preston Institute and Preston and Olin Institute: The Early to have entered upon his task with great enthusiasm. Possessed as he was with a flair Years of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Part II for writing and a ‘tongue for speaking,’ this ex-confederate secret agent brought Clara B. Cox ..................................................................................1 a new dimension of excitement to the school and to the town of Blacksburg.” — page 47 Change Amidst Tradition: The First Two Years of the Burruss Administration at VPI “The Indian Road as agreed to at Lancaster, June the 30th, 1744. The present Faith Skiles .......................................................................................27 Waggon Road from Cohongoronto above Sherrando River, through the Counties of Frederick and Augusta . -

Granville, This Map of Day Lewistown, Pa

Like "The French Letter" found at Fort Granville, this map of the site near present- day Lewistown, Pa., remains a mystery. It was probably done in the late 18th century! but its creator is not known. 154 Pittsburgh History, Winter 1996/97 The Fall of Fort Granville, q 'The French Letter,' <X Gallic Wit on the Pennsylvania Frontier, 1756 James P. Myers, Jr. EVENTS DESCRIBED as "momentous" or "dramatic" often seem to inspire a singleness or simplicity of response by those affected orby those who interpret the events. The mind tries to make sense HISTORICALof things byignoring complexities and subtleties that undermine simple, overwhelming emotional responses. Historians, as well,seek continuities which reinforce their culture's belief inthe cause-and-effect ofhistory. Incidents that seem "to make no sense" are frequently omitted from historical accounts. An historiographic tradition which owes so much to Anglo-Saxon, Germanic, and even Scots- Irish attitudes does not equip most commentators to deal well withfigures nurtured on other values and perspec- tives. Until recent times, for example, most American and English historians have largely ignored the ways in which Native American attitudes and cultures helped to shape the continent's history. 1 Similarly, the bloody record of 18th-century border warfare illustrates how the received historical tradition assesses French actions while tending to ignore the culture and attitudes which underlie those deeds. James P. Myers,Jr., a professor ofEnglish at Gettysburg College, teaches English Renaissance and Irishliterature. Interested in the contributions of the Irish, Scots-Irish, and Anglo-Irish to colonial Pennsylvania history, he is exploring and writing on the 1758 Forbes expedition against FortDuquesne. -

June 15-21, 2017

JUNE 15-21, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFORTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM Proudly presents in Fort Wayne, Indiana ON SALETICKETS FRIDAY ON SALE JUNE NOW! 2 ! ONTICKETS SALE FRIDAYON SALE NOW! JUNE 2 ! ONTICKETS SALE FRIDAY ON SALE NOW! JUNE 2 ! ProudlyProudly presents inpresents Fort Wayne, in Indiana Fort Wayne, Indiana 7KH0RWRU&LW\0DGPDQ5HWXUQV7R)RUW:D\QH ONON SALE SALE NOW! NOW! ON SALEON NOW! SALE NOW!ON SALE NOW! ON SALEON SALE NOW! NOW! ON SALE NOW! WEDNESDAY SEPTEMBER 20, 2017 • 7:30 PM The Foellinger Outdoor Theatre GORDON LIGHTFOOT TUESDAY AUGUST 1, 2017 • 7:30 PM 7+856'$<0$<30 7+856'$<0$<30Fort Wayne, Indiana )5,'$<0$<30THURSDAY)5,'$<0$<30 AUGUST 24,78(6'$<0$<30 2017 • 7:30 PM 78(6'$<0$<30 The Foellinger Outdoor Theatre THE FOELLINGER OUTDOOR THEATRE The Foellinger Outdoor TheatreThe Foellinger TheThe Outdoor Foellinger Foellinger Theatre Outdoor OutdoorThe Foellinger Theatre Theatre Outdoor TheatreThe Foellinger Outdoor Theatre Fort Wayne, Indiana FORT WAYNE, INDIANA Fort Wayne, Indiana Fort Wayne, IndianaFortFort Wayne, Indiana IndianaFort Wayne, Indiana Fort Wayne, Indiana ON SALE ONON NOW!SALE SALE NOW! NOW! ON SALE ON NOW! SALE ON NOW! SALE ON SALE NOW!ON NOW! SALE NOW! ONON SALE SALEON NOW! SALE NOW! NOW!ON SALE NOW!ON SALE ON SALE NOW! NOW! 14 16 TOP 40 HITS Gold and OF GRAND FUNK MORE THAN 5 Platinum TOP 10 HITS Records 30 Million 2 Records #1 HITS RAILROAD! Free Movies Sold WORLDWIDE THURSDAY AUGUST 3, 2017 • 7:30 PM Tickets The Nut Job Wed June 15 9:00 pm MEGA HITS 7+856'$<$8*867307+856'$<$8*86730On-line By PhoneTUESDAY SEPTEMBERSurly, a curmudgeon, 5, 2017 independent • 7:30 squirrel PM is banished from his “ I’m Your Captain (Closer to Home)” “ We’re An American Band” :('1(6'$<$8*86730:('1(6'$<$8*86730 “The Loco-Motion”)5,'$<-8/<30)5,'$<-8/<30 “Some Kind of Wonderful” “Bad Time” www.foellingertheatre.org (260) 427-6000 park and forced to survive in the city. -

The Trail Through Shadow of Ljcaut C"P. from a Phoiogrnph Made by the Author in September, 1909

The Trail through Shadow of lJcaUt C"p. From a phoiogrnph made by the Author in September, 1909. The Wilderness Trail Or The Ventures and Adventures of the Pennsyl vania Traders on the Allegheny Path With Some New Annals of the Old West, and the Records of Some Strong Men and Some Bad Ones By Charles A. Hanna Author of .. The Scotch-Irish" With Eighty Maps alld Illustratiuns In Two Volumes Volume One G. P. Plltnam's Sons New York and London ltDe 1T1111c~erbocllec lIlreo6 1911 CHAPTER XII THE OHIO MINGOES OF THE WHITE RIVER, AND THE WENDATS IERRE JOSEPH DE CELORON, Commandant at Detroit in 1743, P wrote in the month of June of that year to Bcauharnois, the Governor-General of Canada at Quebec, respecting some Indians" who had seated themselves of late years at the White River." These Indians, he reported, were Senecas, Onondagas, and others of the Five Iroquois villages. At their urgent request, Celoron permitted some residents of Detroit to carry goods thither, and had recently sent Sicur Navarre to the post, to make a report thereupon. Navarre's account was trans nUtted to Quebec with this letter. Celoron's letter has been printed in the New York Colonial Doc1tments, but the accompanying report of Sieur Navarre has not heretofore been published. Following is a portion of that report: "Memoir of an inspection made by me, Navarre,l of the trading post where the Frenchman called Saguin carries on trade; of the different nations who are there established, and of the trade which can be de veloped there. -

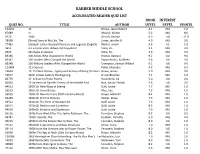

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C. Hale Sipe One cannot travel far in Western Pennsylvania with- out passing the sites of Indian towns, Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca mostly, or being reminded of the Pennsylvania Indians by the beautiful names they gave to the mountains, streams and valleys where they roamed. In a future paper the writer will set forth the meaning of the names which the Indians gave to the mountains, valleys and streams of Western Pennsylvania; but the present paper is con- fined to a brief description of the principal Indian towns in the western part of the state. The writer has arranged these Indian towns in alphabetical order, as follows: Allaquippa's Town* This town, named for the Seneca, Queen Allaquippa, stood at the mouth of Chartier's Creek, where McKees Rocks now stands. In the Pennsylvania, Colonial Records, this stream is sometimes called "Allaquippa's River". The name "Allaquippa" means, as nearly as can be determined, "a hat", being likely a corruption of "alloquepi". This In- dian "Queen", who was visited by such noted characters as Conrad Weiser, Celoron and George Washington, had var- ious residences in the vicinity of the "Forks of the Ohio". In fact, there is good reason for thinking that at one time she lived right at the "Forks". When Washington met her while returning from his mission to the French, she was living where McKeesport now stands, having moved up from the Ohio to get farther away from the French. After Washington's surrender at Fort Necessity, July 4th, 1754, she and the other Indian inhabitants of the Ohio Val- ley friendly to the English, were taken to Aughwick, now Shirleysburg, where they were fed by the Colonial Author- ities of Pennsylvania. -

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN 273 POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 The strategic situation The Appalachian frontier The Ohio Indians Lord Dunmore’s Virginia CHRONOLOGY 17 OPPOSING COMMANDERS 20 Virginia commanders Indian commanders OPPOSING ARMIES 25 Virginian forces Indian forces Orders of battle OPPOSING PLANS 34 Virginian plans Indian plans THE CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE 38 From Baker’s trading post to Wakatomica From Wakatomica to Point Pleasant The battle of Point Pleasant From Point Pleasant to Fort Gower THE AFTERMATH 89 THE BATTLEFIELD TODAY 93 FURTHER READING 94 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 4 British North America in1774 British North NEWFOUNDLAND Lake Superior Quebec QUEBEC ISLAND OF NOVA ST JOHN SCOTIA Montreal Fort Michilimackinac Lake St Lawrence River MASSACHUSETTS Huron Lake Lake Ontario NEW Michigan Fort Niagara HAMPSHIRE Fort Detroit Lake Erie NEW YORK Boston MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND PENNSYLVANIA New York CONNECTICUT Philadelphia Pittsburgh NEW JERSEY MARYLAND Point Pleasant DELAWARE N St Louis Ohio River VANDALIA KENTUCKY Williamsburg LOUISIANA VIRGINIA ATLANTIC OCEAN NORTH CAROLINA Forts Cities and towns SOUTH Mississippi River CAROLINA Battlefields GEORGIA Political boundary Proposed or disputed area boundary -

Chief Richardville House to Be Considered for National Landmark

RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED RETURN SERVICE MIAMI, OK 74355 MIAMI NATION An Official Publication of the Sovereign Miami Nation BOX 1326 P.O. STIGLER, OK 74462 PERMIT NO 49 PERMIT PAID US POSTAGE PR SRT STD PR SRT Vol. 10, No. 2 myaamionki meeloohkamike 2011 Myaamiaki Gather To Preview New Story Book By Julie Olds Myaamia citizens and guests gathered at the Ethel Miller Tribal Traditions Committee and Cultural Resources Of- Moore Cultural Education Center (longhouse) on January fice with the wonderful assistance of our dear friend Laurie 28, 2011 to herald the publication of a new book of my- Shade and her Title VI crew. aamia winter stories and traditional narratives. Following dinner it was finally story time. George Iron- “myaamia neehi peewaalia aacimoona neehi aalhsooh- strack, Assistant Director of the Myaamia Project, hosted kaana: Myaamia and Peoria Narratives and Winter Stories” the evening of myaamia storytelling. Ironstrack, joined is a work 22 years in the making and therefore a labor of by his father George Strack, opened by giving the story love to all involved, especially the editor, and translator, of where the myaamia first came from. Ironstrack gave a Dr. David Costa. number of other stories to the audience and spoke passion- Daryl Baldwin, Director of the Myaamia Project, worked ately, and knowingly, of the characters, cultural heroes, closely with Dr. Costa throughout the translation process. and landscapes intertwined to the stories. The audience Baldwin phoned me (Cultural Resources Officer Julie listened in respectful awe. Olds) in late summer of 2010 to report that Dr. Costa had To honor the closing of the “Year of Miami Women”, two completed the editing process and that the collection was women were asked to read. -

The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730--1795

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795 Richard S. Grimes West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimes, Richard S., "The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4150. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730-1795 Richard S. Grimes Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth A. -

Grey Lock and Theyanoguin: Case Studies in Native Diaspora, Cultural Adaptation and Persistence After King Philip's

James Duggan NEH Living on the Edge of Empire Gateway Regional High School Grades 10-12. Grey Lock and Theyanoguin: Case Studies in Native Diaspora, Cultural Adaptation and Persistence After King Philip’s War Central Historical Question: In what ways did Woronoco and other Native peoples of the Connecticut River Valley survive, adapt, and persist in the years after King Philip’s War? OBJECTIVES Students will know: • Native peoples of the Westfield River Valley and the surrounding region experienced a diaspora in the years after King Philip’s War. • Diverse native peoples survived, persisted, crossed cultural boundaries, and adapted to changing times and circumstances in various ways. • Grey Lock and Theyanoguin followed different paths in their struggles to secure the survival of their people. • The New England frontier was a zone of cultural interaction as well as conflict. Students will: • Research the lives of Grey Lock and Theyanoguin. • Create annotated and illustrated timelines comparing and contrasting the lives of the two leaders. • Analyze and evaluate evidence in primary and secondary sources. • Determine the causes and consequences of Grey Lock’s War and other conflicts. • Write a document-based essay addressing the central question. RESOURCES Baxter, James. "Documentary History of the State of Maine." Baxter Manuscripts (1889): 209-211, 334- 337, 385-387. Internet Archive. Web. 9 Jul 2013. <http://archive.org/details/baxtermanuscript00baxtrich>. Bruchac, Margaret. “Pocumtuck: A Native Homeland.” Historic Deerfield Walking Tour. Historic Deerfield Inc., 2006. Calloway, Colin. Dawnland Encounters: Indians and Europeans in Northern New England. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1991. 84, 114, 136, 154-55, 159, 162, 207. -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

The Dyer Settlement the Fort Seybert Massacre

THE DYER SETTLEMENT THE FORT SEYBERT MASSACRE FORT SEYBERT, WEST VIRGINIA by MARY LEE KEISTER TALBOT A.B., Hollins College M.A., University of Wisconsin Authorized by The Financial Committee of THE ROGER DYER FAMILY ASSOCIATION IN GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGMENT to the SUBSCRIBERS and GRANT G. DYER of Lafayette, Indiana HON. WALTER DYER KEISTER of Huntington, West Virginia DR. WILLIS S. TAYLOR of Columbus, Ohio Wh06e faith and financial backing have made possible this publication Copyright 1937 By Mary Lee Keister Talbot LARSON-DINGLE PRINTING; CO., CHICAGO, ILLINOIS Table of Contents Page Officers of The Roger Dyer Family Association, 1936-37. 4 Foreword . .. 5 Roger Dyer Family Reunion-1935. 7 Roger Dyer Family Reunion-1936. 9 The Dyer Settlement. 11 The Will of Roger Dyer. 23 The Appraisal of Roger Dyer's Estate. 24 The Sail Bill of Roger Dyer's Estate. 26 Brief Genealogical Notes ....................... ,....................... 29 New Interpretations of Fort Seybert. ................................... 38 James Dyer's Captivity-by Charles Cresap Ward ......................... 59 The Grave at Fort Seybert ............................................ 61 The Fort Seybert Memorial Monument. 62 List of Subscribers. 64 lLL USTRATIONS Relief Map of West Virginia ............................... Facing page 7 The Gap in the South Fork River ....................................... 13 Roger Dyer's Warrant to Land-1733 ................................... 16 Where Time Sleeps ................................................... 21 New Drawing of Fort Seybert ......................................... 42 The South Fork Valley at Fort Seybert ....................... Facing page 48 Indian Spoon Carved of Buffalo Horn ................................... 51 The Grave at Fort Seybert. 63 Roger Dyer Family Association Officers for 1936-37 E. Foster Dyer .. ·............................................... Preside: Franklin, West Virginia Allen M. Dyer .............................................. Vice-Preside, Philippi, West Virginia Mrs.