Abstract Nothing Sweet Nothing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU're LONELY: JESSICA STORIES By

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES by Michael Stoneberg This novel-in-stories follows Jessica through the difficulties of her early twenties to her mid- thirties. During this period of her life she struggles with loneliness and depression, attempting to find some form of meaningful connection through digital technologies as much as face-to-face interaction, coming to grips with a non-normative sexuality, finding and losing her first love and dealing with the resultant constant pull of this person on her psyche, and finally trying to find who in fact she, Jessica, really is, what version of herself is at her core. The picture of her early adulthood is drawn impressionistically, through various modes and styles of narration and points of view, as well as through found texts, focusing on preludes and aftermaths and asking the reader to intuit and imagine the spaces between. WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Michael Stoneberg Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2014 Advisor______________________ Margaret Luongo Reader_______________________ Joseph Bates Reader_______________________ Madelyn Detloff TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Revision Page 1 2. Invoice for Therapy Services Page 11 3. Craigslist Page 12 4. Some Things that Make Us—Us Page 21 5. RE: Recent Account Activity Page 30 6. Sirens Page 31 7. Hand-Gun Page 44 8. Hugh Speaks Page 48 9. “The Depressed Person” Page 52 10. Happy Hour: Last Day/First Day Page 58 11. -

Logistics -An Introduction to Supply Chain Management

Logistics Logistics An Introduction to Supply Chain Management Donald Waters © Donald Waters 2003 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2003 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 0–333–96369–5 paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Waters, C. D. J. (C. Donald J.), 1949– Logistics : an introduction to supply chain management / Donald Waters. -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

The Biology and Ecology of Samson Fish Seriola Hippos

The biology of Samson Fish Seriola hippos with emphasis on the sportfishery in Western Australia. By Andrew Jay Rowland This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University 2009 DECLARATION I declare that the information contained in this thesis is the result of my own research unless otherwise cited. ……………………………………………………. Andrew Jay Rowland 2 Abstract This thesis had two overriding aims. The first was to describe the biology of Samson Fish Seriola hippos and therefore extend the knowledge and understanding of the genus Seriola. The second was to uses these data to develop strategies to better manage the fishery and, if appropriate, develop catch-and-release protocols for the S. hippos sportfishery. Trends exhibited by marginal increment analysis in the opaque zones of sectioned S. hippos otoliths, together with an otolith of a recaptured calcein injected fish, demonstrated that these opaque zones represent annual features. Thus, as with some other members of the genus, the number of opaque zones in sectioned otoliths of S. hippos are appropriate for determining age and growth parameters of this species. Seriola hippos displayed similar growth trajectories to other members of the genus. Early growth in S. hippos is rapid with this species reaching minimum legal length for retention (MML) of 600mm TL within the second year of life. After the first 5 years of life growth rates of each sex differ, with females growing faster and reaching a larger size at age than males. Thus, by 10, 15 and 20 years of age, the predicted fork lengths (and weights) for females were 1088 (17 kg), 1221 (24 kg) and 1311 mm (30 kg), respectively, compared with 1035 (15 kg), 1124 (19 kg) and 1167 mm (21 kg), respectively for males. -

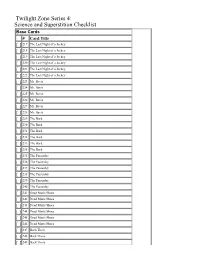

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

Robbie Williams, Calvin Harris, the Cardigans, MØ Og D-A-D Til Tinderbox

Robbie Williams, Calvin Harris, The Cardigans, MØ og D-A-D til Tinderbox. Vi offentliggør nu de første navne for vores ambitiøse TINDERBOX festival, og lægger stærkt ud med to af de største livenavne i verden, et lokalt fænomen fra Odense, et af Sveriges største bands og Danmarks mest elskede festival band. ROBBIE WILLIAMS har solgt mere end 77 millioner albums og singler i sin solokarriere, og har vundet flere BRIT Awards end nogen anden kunstner i historien, i alt 17. Hans seneste album, ”Swing Both Ways” gik nummer et på hitlisten i Storbritannien, det blev hans 11. soloalbum som nummer et, og han matchede dermed Elvis Presleys rekord. Vi er stolte af, og glade for at kunne præsentere Robbie Williams. Sidst han spillede udendørs i Danmark som soloartist, gav han to forrygende koncerter i Parken for mere end 90.000 mennesker. Turneen lover fuld skrue på entertainment og kaldes helt enkelt for ”Let Me Entertain You”. Robbie starter turen i Madrid den 24 marts. Seks af Robbies albums er blandt de 100 bedst solgte albums I Storbritannien, men det er først og fremmest som entertainer og sanger, han har slået de virkelig store rekorder. Robbie har rekorden for flest solgte billetter på én dag - 1.600.000, på hans ”Close Encounters Tour” i 2006. Han har ligeledes spillet den største koncert i Storbritannien nogensinde, da 375.000 så ham på tre aftener på Knebworth i 2003. Klik på dette herlige klip, der lægger stilen for Robbie Williams koncerten i juni på Tinderbox: "Hell is gone and heaven’s here, I’m coming out on tour next year" (RW) Calvin Harris, er verdens mest populære og dermed højst betalte DJ. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

![ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7467/one-night-the-call-center-chetan-bhagat-typeset-by-arun-k-gupta-1187467.webp)

ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]

ONE NIGHT @ THE CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset by: Arun K Gupta] This is someway my story. A great fun, inspirational One! Before you begin this book, I have a small request. Right here, note down three things. Write down something that i) you fear, ii) makes you angry and iii) you don’t like about yourself. Be honest, and write something that is meaningful to you. Do not think too much about why I am asking you to do this. Just do it. One thing I fear: __________________________________ One thing that makes me angry: __________________________________ One thing I do not like about myself: __________________________________ Okay, now forget about this exercise and enjoy the story. Have you done it? If not, please do. It will enrich your experience of reading this book. If yes, thanks Sorry for doubting you. Please forget about the exercise, my doubting you and enjoy the story. PROLOGUE _____________ The night train ride from Kanpur to Delhi was the most memorable journey of my life. For one, it gave me my second book. And two, it is not every day you sit in an empty compartment and a young, pretty girl walks in. Yes, you see it in the movies, you hear about it from friend’s friend but it never happens to you. When I was younger, I used to look at the reservation chart stuck outside my train bogie to check out all the female passengers near my seat (F-17 to F-25)is what I’d look for most). Yet, it never happened. -

Song List 3/2021 1 | Page

Song List 3/2021 1 | Page Contemporary: Artist Rollin in the Deep Adele Someone Adele To Make You Feel My Love Adele I Found You Alabama Shakes Mr. Saxobeat Alexandra Stan Girl on fire Alicia Keys If I ain't got you Alicia Keys No One Alicia Keys Follow me Aly Us Best Day of My Life American Authors Break Free Ariana Grande Sweet but psycho Ava Max Wake Me Up Avicii Poison BBD Love On Top Beyoncé Crazy in Love Beyoncé Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) Beyoncé I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow Black Eyed Peas Let’s Get it Started Black Eyed Peas No Diggity Blackstreet Finessee Bruno Mars ft. Cardi B. Just the Way You Are Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars Marry you Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Let's Go Calvin Harris Sweet Nothing Calvin Harris/Florence Welsh I like it Cardi B Up Cardi B Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Forget You Cee Lo Green Don’t Wake Me Up Chris Brown Yeah 3X Chris Brown International Love Chris Brown Forever Chris Brown Song List 3/2021 2 | Page Turn Up the Music Chris Brown Ain’t No Other Man Christina Aguilera Girls just wana have fun Cyndi Lauper Time After Time Cyndi Lauper Viva La Vida Cold Play Put Your Records On Corinne Bailey Rae Get Lucky Daft Punk Cake by the ocena DNCE Bad Girl Donna Summer Last Dance Donna Summer Perfect Duet Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran I Like It Enrique Iglesias Good Feelin’ Flo Rida Club Can't Handle Me Flo Rida Crazy Gnarles Barkley Without me Halsey I Love It Icona Pop Let It Go Idina Menzel Fancy Iggy Azalea Talk Dirty Jason Derulo -

Ariana Grande, Iggy Azalea Fireball

CURRENT Problem - Ariana Grande, Iggy Azalea Fireball - Pitbull Bang Bang - Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Shake It Off - Taylor Swift Blank Space - Taylor Swift All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor Sing - Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud- Ed Sheeran Jealous - Nick Jonas Empire State of Mind - Jay Z Boom Clap - Charlie XCX Turn Down For What - DJ Snake and Lil Jon Don’t Wake Me Up - Chris Brown Rude - Magic Fancy- Iggy Azalea Get Lucky- Daft Punk Happy-Pharell Williams Talk Dirty To Me-Jason Derulo Slow Down-Selena Gomez Want You Back-Cher Lloyd Animal- Neon Trees Radioactive-Imagine Dragons What Makes You Beautiful-One Direction Dance Again-Jennifer Lopez Uptown Funk- Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven-Bruno Mars Treasure-Bruno Mars Some Nights-Fun Safe And Sound- Capital Cities Wake Me Up- Avicii Wrecking Ball- Miley Cyrus We Can't Stop- Miley Cyrus Wild Ones- Flo rida Club Can't Handle Me- Flo Rida Lights-Ellie Goulding I Love It- Icona Pop Timber- Pitbull Don't Stop The Party-Pitbull Feel This Moment-Pitbull feat. Christina Aguilera We Found Love-Rihanna Only Girl In The World-Rihanna Rude Boy-Rihanna Diamonds-Rihanna S&M-Rihanna Where Have You Been-Rihanna Mr Saxobeat-Alexandra Stan Tonight, Tonight-Hot Chelle Rae Moves Like Jagger-Maroon 5 One More Night-Maroon 5 Animlas - Maroon 5 I’ve Got A Feeling-Black Eyed Peas Applause-Lady Gaga Bad Romance-Lady Gaga Born This Way-Lady Gaga California Gurls-Katy Perry Firework-Katy Perry Roar-Katy Perry Dark Horse-Katy Perry Shake Ya Tail feather-Nelly Raise your Glass-Pink All Summer Long-Kid -

Project Gutenberg Etext Confessions of a Justified Sinner, by Hogg the Complete Title Is: the Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg

Project Gutenberg Etext Confessions of A Justified Sinner, by Hogg The complete title is: The Private Memoirs and Confessions of A Justified Sinner By James Hogg Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. The Private Memoirs and Confessions of A Justified Sinner By James Hogg August, 2000 [Etext #2276] The Project Gutenberg Etext of Robin Hood by J. Walker McSpadden ******This file should be named pmfjs10.txt or pmfjs10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, pmfjs11.txt VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, pmfjs10a.txt Scanned in by Andreas Philipp [email protected] Proofing by Martin Adamson Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. Therefore, we usually do NOT keep any of these books in compliance with any particular paper edition. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, leaving time for better editing. -

Small Gods & Orbital Bodies

ABSTRACT SMALL GODS & ORBITAL BODIES: A THESIS by Anthony F. Ramstetter, Jr. This manuscript is my Master thesis, which I have compiled to fulfill the requirements of a creative writing examination in poetry. It collects diverse thematic pathways into professional and publishable form. The first section includes rough reflections on spirituality, which create worlds within their own respective compass. The second section includes humorous, incidental poems that play with the linkage of the ampersand. The third section meditates on personal relationships and various intimacies. SMALL GODS & ORBITAL BODIES: A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Anthony F. Ramstetter, Jr. Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2013 Advisor ___________________________________ cris cheek Reader ___________________________________ David Schloss Reader ___________________________________ Keith Tuma © Anthony F. Ramstetter, Jr. 2013 Table of Contents DEDICATIONS ................................................................................................................ v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..................................................................................................vi [SMALL GODS] ARS POETICA? .............................................................................................................. 2 FOURSQUARE: METAPOETICS ................................................................................... 3 SOMETIMES I FEEL AS