Landconagendaaugust22 2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

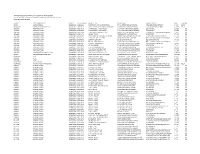

Wisdot Project List with Local Cost Share Participation Authorized Projects and Projects Tentatively Scheduled Through December 31, 2020 Report Date March 30, 2020

WisDOT Project List with Local Cost Share Participation Authorized projects and projects tentatively scheduled through December 31, 2020 Report date March 30, 2020 COUNTY LOCAL MUNICIPALITY PROJECT WISDOT PROJECT PROJECT TITLE PROJECT LIMIT PROJECT CONCEPT HWY SUB_PGM RACINE ABANDONED LLC 39510302401 1030-24-01 N-S FREEWAY - STH 11 INTERCHANGE STH 11 INTERCHANGE & MAINLINE FINAL DESIGN/RECONSTRUCT IH 094 301NS MILWAUKEE AMERICAN TRANSMISSION CO 39510603372 1060-33-72 ZOO IC WATERTOWN PLANK INTERCHANGE WATERTOWN PLANK INTERCHANGE CONST/BRIDGE REPLACEMENT USH 045 301ZO ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583090000 8309-00-00 T SHANAGOLDEN PIEPER ROAD E FORK CHIPPEWA R BRIDGE B020031 DESIGN/BRRPL LOC STR 205 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583090070 8309-00-70 T SHANAGOLDEN PIEPER ROAD E FORK CHIPPEWA R BRIDGE B020069 CONST/BRRPL LOC STR 205 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39583510760 8351-07-60 CTH E 400 FEET NORTH JCT CTH C 400FEET N JCT CTH C(SITE WI-16 028) CONS/ER/07-11-2016/EMERGENCY REPAIR CTH E 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585201171 8520-11-71 MELLEN - STH 13 FR MELLEN CITY LIMITS TO STH 13 CONST RECST CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585201571 8520-15-71 CTH GG MINERAL LK RD-MELLEN CTY LMT MINERAL LAKE RD TO MELLEN CITY LMTS CONST; PVRPLA FY05 SEC117 WI042 CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585300070 8530-00-70 CLAM LAKE - STH 13 CTH GG TOWN MORSE FR 187 TO FR 186 MISC CONSTRUCTION/ER FLOOD DAMAGE CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39585400000 8540-00-00 LORETTA - CLAM LAKE SCL TO ELF ROAD/FR 173 DESIGN/RESURFACING CTH GG 206 ASHLAND ASHLAND COUNTY 39587280070 -

Wastewater Treatment Facilities with Individual WPDES Permits That Do Not Discharge Directly to Lake Michigan

NE Lakeshore TMDL List of Wastewater Treatment Facilities with individual WPDES permits that do not discharge directly to Lake Michigan. List includes information on design flow, current total phosphorus (TP) limits, and current Total Suspended Solids (TSS) limit. * Baseline flow represents the highest annual average flow between 2015 and 2019. **Units for TP and TSS limits are mg/L unless otherwise noted. Design Baseline* Baseline Current TP limit Current TSS limit Waste Permit Outfall Outfall Outfall Flow flow flow Flow mg/L** mg/L** Facility Name Type Number Number Lat Long Receiving Water (MGD) (MGD) year source (average type) (average type) Unnamed Trib to 40 (daily); AGROPUR INC LUXEMBURG Industrial 0050237 009 44.4306 -87.6869 East Twin River NA 0.665 2018 Effluent 0.72 (monthly) 20 (monthly) ALGOMA WASTEWATER TREATMENT FACILITY Municipal 0020745 001 44.6129 -87.4410 Ahnapee River 1 0.743 2019 Effluent 1 (monthly) 10 (monthly) 0.225 (monthly); 0.075 (6 month); 40 (daily); BAKER CHEESE FACTORY INC Industrial 0050521 003 43.7322 -88.1736 Mullet River NA 0.190 2019 Effluent 1 (12 month) 20 (monthly) Unnamed Trib of 40 (daily); BELGIOIOSO CHEESE INC DENMARK Industrial 0051128 007 44.3605 -87.8876 Devils River NA 0.476 2017 Effluent 1 (12 month) 20 (monthly) BELGIUM WASTEWATER TREATMENT Unnamed Trib to FACILITY Municipal 0023353 001 43.5139 -87.8493 Onion River 0.63 0.341 2019 Effluent 0.5 (monthly) 20 (monthly) BEMIS MANUFACTURING COMPANY 0.3 (monthly); 6.7 lbs per day PLANT D Industrial 0027456 001 43.7310 -87.8383 Sheboygan River NA 0.458 2016 Effluent 0.1 (6 month) (daily) BRIESS MALT & INGEDIENTS CO Industrial 0066257 001 44.0917 -87.6548 Manitowoc River NA 2.16 NA Permit 40 (daily) Unnamed Trib to BRILLION WASTEWATER TREATMENT Manitowoc N. -

Appendix B–Wetland Characteristics for 12- Digit Watersheds

Appendix B – Wetland Characteristics for 12-Digit Watersheds APPENDIX B – WETLAND CHARACTERISTICS FOR 12- DIGIT WATERSHEDS B-1 Appendix B – Wetland Characteristics for 12-Digit Watersheds Acres by HUC 12 Watershed Percent of Watershed that is: Original Hydrologic Unit Percent Wetland Potentially Watershed Name Watershed Current Lost Wetland Current Impervious Code Loss (Lost/Orig) Restorable Size Wetland Wetland (Current Wetland Surface Wetland + Lost) 07060005 Apple-Plum ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ 0706000502 Sinsinawa River-Mississippi River ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ 070600050201 Menominee River 19,774 0 5 5 100.00% 0.00% 0.02% 1.54% 070600050202 Frentress Lake-Mississippi River 8,144 422 56 479 11.80% 5.20% 0.55% 4.16% 070600050203 Sinsinawa River 31,580 6 94 100 93.80% 0.00% 0.28% 1.28% 070600050205 Little Menominee River-Mississippi River 20,776 0 46 46 100.00% 0.00% 0.18% 1.19% 0706000503 Galena River ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ 070600050301 Madden Branch 14,227 8 6 14 43.40% 0.10% 0.04% 0.67% 070600050302 Pats Creek-Galena River 22,010 33 55 88 62.80% 0.10% 0.23% 0.91% 070600050303 Shullsburg Branch 20,802 10 534 544 98.20% 0.00% 2.44% 1.23% 070600050304 Blacks Creek-Galena River 10,434 0 46 46 100.00% 0.00% 0.42% 0.83% 070600050305 East Fork Galena River 16,117 0 102 102 100.00% 0.00% 0.63% 1.08% 070600050306 Kelsey Branch-Galena River 32,398 7 150 158 95.30% 0.00% 0.37% 1.30% 0706000505 South Fork Apple River-Apple River ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ ─ 070600050502 South Fork Apple River 19,606 0 31 31 100.00% 0.00% 0.16% 0.74% 070600050503 West Fork Apple River-Apple River 25,732 -

2021 Fishing Guide

2021 Michigan Fishing Guide Rules apply from April 1, 2021 - March 31, 2022 Get the digital guide at Michigan.gov/DNRDigests MICHIGAN FISHING LICENSE INFORMATION & REQUIREMENTS License Items & Fees Purchase your fshing license (and more) online at Michigan.gov/DNRLicenses. Item Type Fee DNR Sportcard $1 All -Species Fishing Licenses Resident Annual $26* Nonresident Annual $76* Senior Annual (Residents 65 or older or Residents who are legally blind – see p. 6) $11* Daily Fish (Resident or Nonresident) $10/day Angler can buy from 1 to 6 consecutive days Voluntary Youth (16 and under) $2* Combo Hunt/Fish Licenses (Base, Annual Fishing, 2 Deer) Hunt/Fish Resident $76* Hunt/Fish Senior Resident $43* Hunt/Fish Nonresident $266* Lost Licenses Lost your license? See the gray box below for instructions on getting a replacement. Fishing license fees are waived for Michigan residents who are veterans with 100% disability or active-duty military (see p. 6). All fshing licenses are good for all species allowed for harvest as indicated in this Fishing Guide. A $1 surcharge is included in the combo hunt and fsh licenses, resident annual, nonresident annual, and senior annual fshing licenses, as noted with the asterisk (*). Revenue generated from these funds will be used to educate the public on the benefts of hunting, fshing and trapping in Michigan, and the impact of these activities on the conservation, preservation and management of the state’s natural resources in accordance with statute. Learn more at Michigan.gov/DNR. Who needs a Michigan fshing license? Any adult actively assisting a minor must have A license is required when targeting fsh, a fshing license. -

Board of Supervisors

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS 305 E. WALNUT STREET, P. O. BOX 23600 GREEN BAY, WISCONSIN 54305-3600 ADMINISTRATION COMMITTEE PHONE (920) 448-4015 FAX (920) 448-6221 Rick Schadewald, Chair; John Vander Leest, Vice Chair Patrick Hopkins, Jim Murphy, Thomas Peters ADMINISTRATION COMMITTEE MEETING THURSDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2020 5:30 p.m. BROWN COUNTY CENTRAL LIBRARY 515 Pine St, Green Bay, WI 54301 Access will be through the Pine Street entrance and doors will open at 5:00 pm. Social distancing will be practiced and hand sanitizer available. NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT THE COMMITTEE MAY TAKE ACTION ON ANY ITEM LISTED ON THE AGENDA I. Call to Order. II. Approve/Modify Agenda. III. Approve/Modify Minutes of October 15, 2020. 1. Review minutes of: a. None. Comments from the Public Communications 2. Communication from Supervisor Dantinne re: To look at ways to expand the internet services to the rural areas. Referred from October County Board. 3. Communication from Supervisor Schadewald re: Request the Administration prepare an accounting of initial and ongoing costs of having computers for each supervisor. Also, I request the Administration do an RFP on computer software for meeting agenda and minutes capability. Referred from October County Board. Resolutions & Ordinances 4. Resolution Supporting Increased Funding for Aging and Disability Resource Centers (20-112R). 5. Resolution to Authorize Easement between Brown County and NEW Water for Underground Utilities to Benefit Fairgrounds Development (20-113R). 6. Resolution to Authorize Reciprocal Easement between Brown County and Private Parcel within Park Boundaries (21-114R). 7. Resolution Regarding Table of Organization Change for the Port & Resource Recovery Department – Resource Recovery Associate (20-117R). -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form ROCK MILL, Maribel Vicinity, Manitowoc Co., Wise

NFS Form 10-900 OMB NO. 1024-0018 EXP. 12/31/84 United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service For HCRS use only National Register of Historic Places recelvtd Inventory — Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries — complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Rock Mill and/or common N/A street & number CTH R not for publication city, town Maribel _X_ vicinity of congressional district Sixth state Wisconsin code 55 county Manitowoc code 071 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture y museum , X building(s) J£ _ private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered x yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A nr» military OthAf name Robert L. Lyman street & number Route 1 city, town Maribel vicinity of state Wisconsin 54227 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Manitowoc County Courthouse street & number South 8th and Washington streets Manitowoc state Wisconsin 54220 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Wisconsin Tnvpnf nry of i r Pi has this property been determined elegible? __ yes % no federal X state county local depository for survey records state Historical Society of Wisconsin 816 State Street city, town Madison state Wisconsin 53706 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated X unaltered X original site good ruins altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Rock Mill in rural Maribel, Manitowoc County is a two-story-plus-attic rectangular frame building with tin-covered gable roof and coursed limestone (originally rubble) foundation. -

West Twin River Watersheds Watershed

Wisconsin West Twin River Watersheds Watershed 2010 Water Quality Management Plan Update August 2010 Twin Door Kewaunee Basin, Wisconsin Th e West Twin River watershed is one of seven watersheds within the Twin-Door-Ke- waunee River Basin. Th e West Twin River watershed is located in north central Manito- woc and southeastern Brown Counties, with a small portion extending into southwestern Kewaunee County (Map 1). Twenty-nine (29) rivers and streams cover 130 miles through the watershed. Th ere are Contents fi ve lakes that are 10 acres or larger in the Watershed Details . 1 watershed. A number of spring ponds and Population and Land Use . 1 wetlands are identifi ed as “quality wetlands” Hydrology . 2 by the state’s coastal wetland inventory and Ecological Landscapes . 2 Map 1: West Twin Watershed Historical Note . 3 the USFWS Special Wetlands Inventory Study are also located in the area. Watershed Condition . 3 Priority Issues & Water Quality Goals . .3 Watershed Details Overall Condition . .4 Lake Health . .7 Wetland Health . .8 Population and Land Use Groundwater . .8 This watershed is primarily agricultural, with Waters of Note . .8 a smattering of towns and villages through- Aquatic Invasives . .9 out the land area (Figure 1) . Shoto, Rock- Watershed Actions . 9 wood, Kellnersville, Maribel, Cooperstown, Francis Creek, Denmark, Shirley and Langes Priority Issues . .9 Corners are located in this watershed, and Water Quality Goals . .9 a portion of the city of Two Rivers also lies Projects and Grants . 10 within the watershed boundaries. Monitoring . 11 Figure 1: Land Use West Twin Watershed Recommendations . 12 Agriculture is the primary land use and, de- Contributors: . -

Brown County Parks and Outdoor Recreation Plan 2017-2022

2017 Adopted: 5/171/2017 | Page 2 | Page Brown County Parks and Outdoor Recreation Plan 2017-2022 Plan Adopted: May 17, 2017 Prepared by the Brown County Planning Commission Brown County Parks Department Park Plan Steering Committee And Various Focus Groups In cooperation with the Brown County Education & Recreation Committee Brown County Planning Commission Planning and Land Services Department 305 E. Walnut Street P.O. Box 23600 Green Bay, WI 54305-3600 www.co.brown.wi.us/planning 3 | Page Plan Development Team Brown County Executive: Troy J. Streckenbach Brown County Board of Supervisors: Paul Ballard Erik Hoyer Mark Becker Dave Kaster Jamie Blom James Kneiszel Joan Brusky Dave Landwehr Patrick Buckley Kathy Lefebvre Corrie Campbell Aaron Linssen Bill Clancy Andy Nicholson Norbert Dantinne, Jr. Richard Schadewald Thomas DeWane Tom Sieber Bernie Erickson John Van Dyck Patrick Evans John Vander Leest Staush Gruszynski Guy Zima Brown County Education & Recreation Committee: Paul Ballard Kathy Lefebvre Corrie Campbell John Van Dyck Staush Gruszynski Park Plan Steering Committee: Neil Anderson, B.C. Zoo & Parks Dan Theno, Brown County Citizen Jon Bechle, B.C. Land & Water Conservation Beth Ulatowski, G.B. Visitor & Convention Bureau Corrie Campbell, Brown County Board Jen Van Den Elzen, Live 54218 Mark Ernst, InCompetition Sports John Van Dyck, Brown County Board Judy Knudsen, U.W. Extension Allyson Watson, U.W. Extension 4 | Page Brown County Parks Department: Neil Anderson, Zoo/Parks Director Dani Warner, Assistant Naturalist Matt Kriese, -

Manitowoc County Comprehensive Plan”

Prepared by: Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission MANITOWOC COUNTY 20-YEAR COMPREHENSIVE PLAN VOLUME I: COUNTY PLAN VOLUME II: MANITOWOC COUNTY RESOURCES Prepared by: Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission 441 South Jackson Street Green Bay, WI 54301 (920) 448-2820 December 15, 2009 The preparation of this document was financed through contract #07011-05 between Manitowoc County and the Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission with financial assistance from the Wisconsin Department of Administration, Division of Intergovernmental Relations. Portions of the transportation element of this plan were underwritten by the Commission’s Regional Transportation Planning Program which is funded by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation and portions of the economic element were underwritten by the Commission’s Economic Development Program which is funded by the Economic Development Administration. Cover photography provided by the Economic Development Corporation of Manitowoc County, S.S. Badger, and Ron Hoerth. MANITOWOC COUNTY WISCONSIN COUNTY EXECUTIVE: Bob Ziegelbauer COUNTY CLERK: Jamie Aulik CORPORATION COUNSEL Steven Rollins COUNTY BOARD CHAIRPERSON: James Brey st COUNTY BOARD VICE CHAIRPERSONS: Kevin Behnke – 1 Edward Rappe – 2nd COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS: SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 1: Edward Rappe SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 2: Kevin Schmidt SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 3: Kathie Bundy SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 4: James Brey SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 5: Gregory Dufek SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 6: Paul Hansen SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 7: Norbert Vogt SUPERVISORY DISTRICT 8: Paul -

Drainage-Area Data for Wisconsin Streams

Click here to return to USGS publications U.S . Geological Survey Open-File Report 83-933 Drainage-Area Data For Wisconsin Streams Prepared in cooperation with the WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Drainage-Area Data For Wisconsin Streams By E .W . Henrich, U.S . Geological Survey, and D.N . Daniel, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources U .S . Geological Survey Open-File Report 83-933 Prepared in cooperation with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR . WILLIAM P. CLARK . SE,CRETAR } GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L . Peck, Director For additional information write to : Copies of this report can be purchased from : District Chief Open-File Services Section U.S. Geological Survey Western Distribution Branch 1815 University Avenue U.S . Geological Survey Madison, Wisconsin 53705-4096 Box 25425, Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225 (Telephone : (303) 234-5888) CONTENTS Page Abstract . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... .. .. ... ... .. .. .. .. ... .. ... .. .. .. .. ..1 Introduction . .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ... .. ..1 Explanation of drainage area tables . .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... .. ... ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. ... .. ... .. .. .2 Station number .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. ... .. .. ... .. . -

2020 Michigan Fishing Guide Rules Apply from April 1, 2020 - March 31, 2021

2020 Michigan Fishing Guide Rules apply from April 1, 2020 - March 31, 2021 Get the digital guide at Michigan.gov/DNRDigests TM MICHIGAN FISHING LICENSE INFORMATION & REQUIREMENTS License Items & Fees Purchase your fishing license (and more) online at Michigan.gov/DNRLicenses. Item Type Fee DNR Sportcard $1 All-Species Fishing Licenses Resident Annual $26* Nonresident Annual $76* Senior Annual (Residents 65 or older or Residents who are legally blind – see p. 6) $11* Daily Fish (Resident or Nonresident) $10/day Angler can buy from 1 to 6 consecutive days Combo Hunt/Fish Licenses (Base, Annual Fishing, 2 Deer) Hunt/Fish Resident $76* Hunt/Fish Senior Resident $43* Hunt/Fish Nonresident $266* Lost Licenses Lost your license? See the gray box below for instructions on getting a replacement. Fishing license fees are waived for Michigan residents who are veterans with 100% disability or active-duty military (see p. 6). All fishing licenses are good for all species allowed for harvest as indicated in this Fishing Guide. A $1 surcharge is included in the combo hunt and fish licenses, resident annual, nonresident annual, and senior annual fishing licenses, as noted with the asterisk (*). Revenue generated from these funds will be used to educate the public on the benefits of hunting, fishing and trapping in Michigan, and the impact of these activities on the conservation, preservation and management of the state’s natural resources in accordance with statute. Learn more at Michigan.gov/DNR. Who needs a Michigan fishing license? Any adult actively assisting a minor must have A license is required when targeting fish, a fishing license.