The Epigraphia Carnatica Digitization Project Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoysala King Ballala Iii (1291-1342 A.D)

FINAL REPORT UGC MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT on LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA III (1291-1342 A.D) Submitted by DR.N.SAVITHRI Associate Professor Department of History Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s Arts and Commerce College, Mysore-24 Submitted to UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION South Western Regional Office P.K.Block, Gandhinagar, Bangalore-560009 2017 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I would like to Express My Gratitude and Indebtedness to University Grants Commission, New Delhi for awarding Minor Research Project in History. My Sincere thanks are due to Sri.Paramashivaiah.S, President of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I am Grateful to Prof.Panchaksharaswamy.K.N, Honorary Secretary of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I owe special thanks to Principal Sri.Dhananjaya.Y.D., Vice Principal Prapulla Chandra Kumar.S., Dr.Saraswathi.N., Sri Purushothama.K, Teaching and Non-Teaching Staff, members of Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s College, Mysore. I also thank K.B.Communications, Mysore has taken a lot of strain in computerszing my project work. I am Thankful to the Authorizes of the libraries in Karnataka for giving me permission to consult the necessary documents and books, pertaining to my project work. I thank all the temple guides and curators of minor Hoysala temples like Belur, Halebidu. Somanathapura, Thalkad, Melkote, Hosaholalu, kikkeri, Govindahalli, Nuggehalli, ext…. Several individuals and institution have helped me during the course of this study by generously sharing documents and other reference materials. I am thankful to all of them. Dr.N.Savithri Place: Date: 2 CERTIFICATE I Dr.N. Savithri Certify that the project entitled “LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA iii (1299-1342 A.D)” sponsored by University Grants Commission New Delhi under Minor Research Project is successfully completed by me. -

Changing Demographic Structure of Hassan District, Karnataka, India: a Geographical Perspective

Scholarly Research Journal for Humanity Science & English Language, Online ISSN 2348-3083, SJ IMPACT FACTOR 2017: 5.068, www.srjis.com PEER REVIEWED JOURNAL, AUG-SEPT 2018, VOL- 6/29 CHANGING DEMOGRAPHIC STRUCTURE OF HASSAN DISTRICT, KARNATAKA, INDIA: A GEOGRAPHICAL PERSPECTIVE Ravisha. G. M.1 & H. Nagaraj2, Ph. D. 1Research Scholar, Dos in Geography, University of Mysore-570006, Karnataka Email: [email protected] 2MA. M.Phil., Ph.D. , Research Guide, Professor, DOS in Geography, University of Mysore-570006, Karnataka Email: [email protected] Abstract The present paper aims to analyse the total and sex-wise causes of dynamic growth and distribution of population. Population growth is inevitable outcome of the demographic transition, primarily as a result of high fertility and secondarily mortality declines and mobility in view of rapidly growing or population explosion. Growth of population is the change in the number in a particular area between two given points of time. As described in the preceding paper, the population of our ancestors, a few million years ago, was confined to Africa and numbered only in Lakh. By the time our ancestors invented agriculture, the information started passing from generation to generation. The transmission of knowledge about hunting, gathering and preparation of food helped in expansion of agriculture and growth of population. The growth of population was, however, not continuous after the agricultural Revolution. Civilization rose, flourished and disintegrated; periods of good and bad weather occurred; and famine and war took their toll. Despite fluctuations in the birth and death rates, agriculture permitted the existence not only of higher population densities, and settled village life, but also of large scale cooperative ventures, specialization of labour, development of crafts and social stratification, the growth and development of irrigation and the emergence of towns and cities concentrated of economic power in the hands of numerically small elite. -

Executive Summary

1 Pre-feasibility Report for Limestone and Dolomite Mine of M/s. Mysore Minerals Limited, Bagalkot. CHAPTER – 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Limestone and dolomite Mine 1 Prepared By METAMORPHOSISSM Project Consultants Pvt. Ltd., Bengaluru 2 Pre-feasibility Report for Limestone and Dolomite Mine of M/s. Mysore Minerals Limited, Bagalkot. CHAPTER 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 About the Company / Proponent M/s. Mysore Minerals Limited (MML) has been a dynamic player in the Mining field and has been responsible for the efficient harnessing of these resources. MML has been involved in the Mining Business since 1966 and today is a recognized name in the industry with high competent and scientific methods to its credit. Capitalizing on this natural resource of Karnataka and acting as an agent of the Government has made MML a vital link in the Local as well as Global trade relations. MML work with sufficient infrastructure that is designed to optimize time and effort. Retaining quality standards is a priority to ensure that we satisfy our clients from all over the world. MML is having 17 quarries, 45 mines, 38 years of experience, Eco-Friendly exploration and Mining technologies. Background, Aims and Achievements of the Organization M/s. Mysore Minerals Limited, a fully owned Company of Government of Karnataka was established in the year 1966 by taking over the assets of the erstwhile Board of Mineral Development. The Company is registered under the Companies Act 1956. Initially, the Company had confined its activities to exploration, production and marketing of the various minerals available in the State. The prominent minerals which were the main resource of the Company were Chromite, Manganese and Iron Ore. -

PT EC Records.Pdf

Details of Files Under KET, KLT and PT Acts manualy received by way of transfer due to Re-Organazation of the Department vide CCT Circular No.18 dated 27-07-2011. The related softwear has not been transfered to this office and hence the said files are yet to be taken into the system ARASIKERE FILES EC FILES 134 P03701041 K G NATARAJA VIDYANIKETANA PUBLIC SCHOOL BANAVARA 135 P03701051 VIVEKANANDA EDUCTIONA SOCIETY ARASIKERE 136 P03712398 VEERABHADRESHWARA RURAL HIGHSCHOOL KANAKATTE 137 p03712156 yalanadu jagadguru vidyasamsthe arasikere 138 P03700943 VIDYARANYA VIDYA SAMSTHE KANAKATTE 139 P03701038 SHARADHSA ENGLISH SCHOOL ARASIKERE 140 P03712404 SBB HIGH SCHOOL HARALAKATTE 141 P03712404 SHIVANANJUNDESHWARA SAMSKRUTHA PATASHALA KANAKATTE 142 P03712407 SWARNAGOWRI HOGH SCHOOL MADALU 143 P03712403 SSDS HIGH SCHOOL NAGENAHALLI 144 4191000196 SHANKARESHWARA SWAMY VIDYA SAMSTHE DUMMENEHALLI 145 P03701131 SHANKARESHWARA HIGH SCHOOL CHIKKAMMANAHALLI 146 P03701258 SHIVALINGSHSWAMY SAMYUKATA PUC KITTANAKERE 146 P03712503 A V SHIVALINGAMMA HIGH SCHOOL AGGUNDA 147 P03700945 RASTRIYA VIDYA SHALA ARASIKERE 148 P03701054 SEVASANKALPA VIDYASAMSTHE ARASIKERE 149 P03701159 PRAGATHISHEELA RURAL HIGH SCHOOL S DIGGENAHALLI 150 P03700924 PRATHIBHA EDUCATION TRUST ARASIKERE 151 P03701033 PARVATHAMMA VIDYA SAMSTHE ARASIKERE 152 P03701257 NIRVANASIDDESHWARA HIGH SCHOOL RAMPURA 153 P03701022 NAVABHARATHHGH SCHOOL BAGIVALU 154 P03701022 NAVABHARATH ITI BAGIVALU 156 P037001097 MAHADESHWARA RURAL EDUCATION TRUST RANGANAYAKANAKOPPALU 157 P03701159 SRI MARUTHI HIGH -

Mysore Tourist Attractions Mysore Is the Second Largest City in the State of Karnataka, India

Mysore Tourist attractions Mysore is the second largest city in the state of Karnataka, India. The name Mysore is an anglicised version of Mahishnjru, which means the abode of Mahisha. Mahisha stands for Mahishasura, a demon from the Hindu mythology. The city is spread across an area of 128.42 km² (50 sq mi) and is situated at the base of the Chamundi Hills. Mysore Palace : is a palace situated in the city. It was the official residence of the former royal family of Mysore, and also housed the durbar (royal offices).The term "Palace of Mysore" specifically refers to one of these palaces, Amba Vilas. Brindavan Gardens is a show garden that has a beautiful botanical park, full of exciting fountains, as well as boat rides beneath the dam. Diwans of Mysore planned and built the gardens in connection with the construction of the dam. Display items include a musical fountain. Various biological research departments are housed here. There is a guest house for tourists.It is situated at Krishna Raja Sagara (KRS) dam. Jaganmohan Palace : was built in the year 1861 by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III in a predominantly Hindu style to serve as an alternate palace for the royal family. This palace housed the royal family when the older Mysore Palace was burnt down by a fire. The palace has three floors and has stained glass shutters and ventilators. It has housed the Sri Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery since the year 1915. The collections exhibited here include paintings from the famed Travancore ruler, Raja Ravi Varma, the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and many paintings of the Mysore painting style. -

Brief Industrial Profile of HASSAN District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of HASSAN District MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone 91 080 23151581,82,83 Fax: 91 080 23144506 e-mail:[email protected] 1 Web- www.msmedibangalore.gov.in/ Page HASSAN DISTRICT MAP WITH TALUKS 2 Page FOREWARD The Micro, Small and, Medium Enterprises, Development Institute (earlier called SISI), under Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India, Bangalore is one of the prime organizations in Karnataka, engaged in the promotion and development of Industries in the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises. As a part of the promotional and developmental activities, the Institute conducts studies on the Status and performance of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in the State. The District profile is one such report compiled and updated under District Industry Development Plan of the Institute assigned by Office of the Development Commissioner (SSI), New Delhi. This report contains the present status of economy, geographical information, statistical data relating to MSME’s in each district, salient features of the progress of the different sectors of the each district of Karnataka and performance of industries particularly in Micro, Small and Medium industries. I am happy to appreciate the efforts put in by all the offices and staff in this institute especially S/Shri. B.N.Sudhakar, Deputy Director,Sri. P.V.Raghavendra, Asst.Director (ISS), Sri.K.Channabasavaiah and Smt. D.T.Vijayalakshmi . Asst.Director (Stat) in collecting the latest information available form different departments of Government of Karnataka and in bringing out this Industrial Profile report. -

Cropping Pattern and Crop Ranking of Mysore District

[Ningaraju et. al., Vol.5 (Iss.4): April, 2017] ISSN- 2350-0530(O), ISSN- 2394-3629(P) ICV (Index Copernicus Value) 2015: 71.21 IF: 4.321 (CosmosImpactFactor), 2.532 (I2OR) InfoBase Index IBI Factor 3.86 Science CROPPING PATTERN AND CROP RANKING OF MYSORE DISTRICT Dr. Ningaraju *1, Dr. S Arun Das 2 *1 Lecturer in Geography, University Evening College, University of Mysore, Mysuru, India 2 Associate Professor, Department of Geography, University of Mysore, Mysuru, India DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v5.i4.2017.1827 Abstract With the limited resources of land and water in hand, their optimum use is a must to for increased production of food grains to the demands of increasing population. The productivity in any area can be substantially raised by growing the crops suitable to the area with the help of newly developed agricultural techniques. Rainfed crops would continue to dominate in the agriculture of Mysore district. Keywords: Cropping Pattern; Crop Ranking. Cite This Article: Dr. Ningaraju, and Dr. S Arun Das. (2017). “CROPPING PATTERN AND CROP RANKING OF MYSORE DISTRICT.” International Journal of Research - Granthaalayah, 5(4), 334-338. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v5.i4.2017.1827. 1. Introduction The selection of crops is very important, in the agro - climatic conditions of the district under study. The cropping pattern is based on both time and space sequence of crops. The variety in cropping pattern is the result of physical economical and social factors. The physical environment provides a wide range of possibilities for growing crops, but the social and economical conditions determine as to which the crops to be grown are and how much of it is to be devoted to different crops. -

Forest Watchers Recruitment 2011 Answer Key Correct Options in Each Question Are Marked in Red

Forest Watchers Recruitment 2011 Answer Key Correct options in each question are marked in red. 1. The cube of (-2/3) is- (A) 8/27 (B) 8/9 (C) -8/27 (D) None of these. 2. The speed of 90 kilometres per hour is equal to- (A) 0.25 metres per second. (B) 2.5 metres per second. (C) 25 metres per second. (D) None of these. 3. If the circumference of a circle is 44 cms. Its area will be (using π = 22/7) - (A) 98 π square cms. (B) 49 π square cms. (C) 7 π square cms. (D) None of these. 4. 16x0.002= (A) 32 (B) 3.20 (C) 0.32 (D) None of these. 5. Among 3/5, 5/7 and 13/15, which is the largest in numerical value? (A) 3/5. (B) 5/7. (C) 13/15. (D) None of these as all are equal. 6. The total surface area of a cubical box with each side being 7 cms is - (A) 294 sq. cms (B) 343 sq. cms. (C) 392 sq. cms. (D) None of these. 7. {3.000 + 1.021 – 0.933 } equals (A) 3.808 (B) 3.088 (C) 3.888 (D) None of these. 8. Sandalwood powder contains heartwood and whitewood in the ratio 3:8. In 440 kgs. Of Sandalwood powder, the weight of heartwood will be- 1 (A) 120 kgs. (B) 320 kgs. (C) 48.4 kgs. (D) None of these. 9. The price of rosewood timber is 12% more than that of teak. If price of teak is Rs 1300 per cubic feet, the price of rosewood is- (A) Rs 1312 per cubic feet. -

Mandya District Human Development Report 2014

MANDYA DISTRICT HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2014 Mandya Zilla Panchayat and Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department Government of Karnataka COPY RIGHTS Mandya District Human Development Report 2014 Copyright : Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department Government of Karnataka Published by : Mandya Zilla Panchayat, Government of Karnataka First Published : 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior permission by Zilla Panchayat and Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department, Government of Karnataka Printed by : KAMAL IMPRESSION # 54, Sri Beereshwara Trust Camplex, SJCE Road, T.K. Layout, Mysore - 570023. Mobile : 9886789747 While every care has been taken to reproduce the accurate data, oversights / errors may occur. If found convey it to the CEO, Zilla Panchayat and Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department, Government of Karnataka VIDHANA SOUDHA BENGALURU- 560 001 CM/PS/234/2014 Date : 27-10-2014 SIDDARAMAIAH CHIEF MINISTER MESSAGE I am delighted to learn that the Department of Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics is bringing out District Human Development Reports for all the 30 Districts of State, simultaneously. Karnataka is consistently striving to improve human development parameters in education, nutrition and health through many initiatives and well-conceived programmes. However, it is still a matter of concern that certain pockets of the State have not shown as much improvement as desried in the human development parameters. Human resource is the real wealth of any State. Sustainable growth and advancement is not feasible without human development. It is expected that these reports will throw light on the unique development challenges within each district, and would provide necessary pointers for planners and policy makers to address these challenges. -

District Census Handbook, Mandya, Part X-A, B, Series-14,Mysore

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 S E R I E S-14 MYSORE DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK MANDYA DISTRICT PART X-A: TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY PART X-B: PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT P. PAD MAN A B H A OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MYSORE 24 12 0 24 ... 72 MILES m1f~CD)U -·!~.r-~=.~~~~!~~==~!;;If"!~ : iii: 20 0 20 40 60 eo 100 klt.OM£TRES ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS, 1971 STA TE BOUNDARY DISTRICT " TALUk " STATE CAPITAL * OISTRICT HEADQUARTERS @ TALUk o T. Naulput - ThirumaI<udIu Naulpur Ho-Hoopct H-HubU ANDHRA PRADESH CHELUVANARA YANA TEMPLE, MELKOTE (Mot{f on the cover) The illustration on the cover page represents the temple dedicated to Krishna as CheluVG Pulle-Raya at Melkote town in Mandya district. The temple is a square building of great dimensions but very plain in design. The original name of the principal deity is said to .have been Rama Priya. According to tradition, Lord Narayana of Melkote appeared in a dream to Sri Ramanuja (the 12th century Vaishnava Saint and propounder of the philosophy of Visishtadvait(!) and said to him that He was awaiting him on Yadugiri Hill. Thereupon, v,:ith the assistance of .Hoysala King Vishnu vardhana (who had received tapta-mudra from Ramanuja and embraced Vaishnavism) he discovered the idol which lay covered by an ant-hill which he excavated and worshipped. This incident is said to have occurred in the month of Tai in Bahudharaya year. A temple \.vas erected for Lord Narayana over the ant-hill and the installation of tlle image took place in 1100 A.D. -

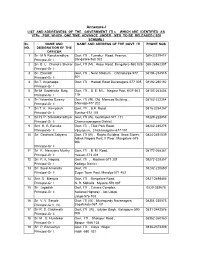

Annexure-I LIST and ADDRESSESS of the GOVERNMENT ITI S WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS Vtps for WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES to BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL

Annexure-I LIST AND ADDRESSESS OF THE GOVERNMENT ITI s WHICH ARE IDENTIFIED AS VTPs FOR WHICH ONE TIME ADVANCE UNDER MES TO BE RELEASED ( SDI SCHEME ) SL. NAME AND NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE GOVT. ITI PHONE NOS NO. DESIGNATION OF THE OFFICER 1 Sri M N Renukaradhya Govt. ITI , Tumakur Road, Peenya, 080-23379417 Principal-Gr I Bangalore-560 022 2 Sri B. L. Chandra Shekar Govt. ITI (M) , Hosur Road, Bangalore-560 029 080-26562307 Principal-Gr I 3 Sri Ekanath Govt. ITI , Near Stadium , Chitradurga-577 08194-234515 Principal-Gr II 501 4 Sri T. Anjanappa Govt. ITI , Hadadi Road Davanagere-577 005 08192-260192 Principal-Gr I 5 Sri M Sadathulla Baig Govt. ITI , B. E. M.L. Nagara Post, KGF-563 08153-263404 Principal-Gr I 115 6 Sri Yekantha Swamy Govt. ITI (W), Old Momcos Building, , 08182-222254 Principal-Gr II Shimoga-577 202 7 Sri T. K. Kempaiah Govt. ITI , B.H. Road, 0816-2254257 Principal-Gr II Tumkur-572 101 8 Sri H. P. Srikanataradhya Govt. ITI (W), Gundlupet-571 111 08229-222853 Principal-Gr II Chamarajanagara District 9 Smt K. R. Renuka Govt. ITI , Tilak Park Road, 08262-235275 Principal-Gr II Vijayapura, Chickamagalur-577 101 10 Sri Giridhara Saliyana Govt. ITI (W) , Raghu Building Urwa Stores, 0824-2451539 Ashok Nagara Post, II Floor, Mangalore-575 006. Principal-Gr II 11 Sri K. Narayana Murthy Govt. ITI , B. M. Road, 08172-268361 Principal-Gr II Hassan-573 201 12 Sri P. K. Nagaraj Govt. ITI , Madikeri-571 201 08272-228357 Principal-Gr I Kodagu District 13 Sri Syed Amanulla Govt. -

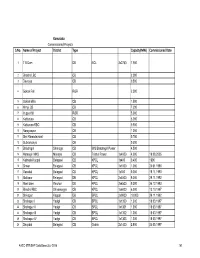

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 1 T B Dam DB NCL 3x2750 7.950 2 Bhadra LBC CB 2.000 3 Devraya CB 0.500 4 Gokak Fall ROR 2.500 5 Gokak Mills CB 1.500 6 Himpi CB CB 7.200 7 Iruppu fall ROR 5.000 8 Kattepura CB 5.000 9 Kattepura RBC CB 0.500 10 Narayanpur CB 1.200 11 Shri Ramadevaral CB 0.750 12 Subramanya CB 0.500 13 Bhadragiri Shimoga CB M/S Bhadragiri Power 4.500 14 Hemagiri MHS Mandya CB Trishul Power 1x4000 4.000 19.08.2005 15 Kalmala-Koppal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x400 0.400 1990 16 Sirwar Belagavi CB KPCL 1x1000 1.000 24.01.1990 17 Ganekal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x350 0.350 19.11.1993 18 Mallapur Belagavi DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 29.11.1992 19 Mani dam Raichur DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 24.12.1993 20 Bhadra RBC Shivamogga CB KPCL 1x6000 6.000 13.10.1997 21 Shivapur Koppal DB BPCL 2x9000 18.000 29.11.1992 22 Shahapur I Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1300 1.300 18.03.1997 23 Shahapur II Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1301 1.300 18.03.1997 24 Shahapur III Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1302 1.300 18.03.1997 25 Shahapur IV Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1303 1.300 18.03.1997 26 Dhupdal Belagavi CB Gokak 2x1400 2.800 04.05.1997 AHEC-IITR/SHP Data Base/July 2016 141 S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 27 Anwari Shivamogga CB Dandeli Steel 2x750 1.500 04.05.1997 28 Chunchankatte Mysore ROR Graphite India 2x9000 18.000 13.10.1997 Karnataka State 29 Elaneer ROR Council for Science and 1x200 0.200 01.01.2005 Technology 30 Attihalla Mandya CB Yuken 1x350 0.350 03.07.1998 31 Shiva Mandya CB Cauvery 1x3000 3.000 10.09.1998