Revitalization and Modernization of Old Havana, Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961

Nikolaus Böttcher Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961 In the late afternoon of 4 March 1762 the British war fleet left the port of Spithead near Portsmouth with the order to attack and conquer “the Havanah”, Spain’s main port in the Caribbean. The decision for the conquest was taken after the new Spanish King, Charles III, had signed the Bourbon family pact with France in the summer of 1761. George III declared war on Spain on 2 January of the following year. The initiative for the campaign against Havana had been promoted by the British Prime Minister William Pitt, the idea, however, was not new. During the “long eighteenth century” from the Glorious Revolution to the end of the Napoleonic era Great Britain was in war during 87 out of 127 years. Europe’s history stood under the sign of Britain’s aggres sion and determined struggle for hegemony. The main enemy was France, but Spain became her major ally, after the Bourbons had obtained the Spanish Crown in the War of the Spanish Succession. It was in this period, that America became an arena for the conflict between Spain, France and England for the political leadership in Europe and economic predominance in the colonial markets. In this conflict, Cuba played a decisive role due to its geographic location and commercial significance. To the Spaniards, the island was the “key of the Indies”, which served as the entry to their mainland colonies with their rich resources of precious metals and as the meeting-point for the Spanish homeward-bound fleet. -

City of Port-Of-Spain Mass Egress Plan Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Port-of-Spain (POS), the Capital City of Trinidad and Tobago is located in the county of St. George. It has a residential population of 49,031 and a population density of 4,086. Moreover, it has an average transient population on any given day of 350,000 persons. The Port of Spain Corporation (POSC) is vulnerable to a number of natural, man-made and technological hazards. The list of natural hazards includes, but not limited to, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes and landslides. Chiefly and most frequent among the natural hazards is flooding. When this event occurs, the result is excessive street flooding that inhibits the movement of individuals in and out of the City for approximately two-three hours, until flood waters subside. The intensity of the event is magnified by concurrent high tide. The purpose of the City of Port-of-Spain Mass Egress Plan is to address the safe and strategic movement of the mass number of people from places of danger in POS to areas deemed safe. This plan therefore endeavours to facilitate planned and unplanned egress of persons when severe flooding occurs in the City. Levels of Egress Fundamentally, the City of Port-of-Spain Mass Egress Plan establishes a three-tiered egress process: . Level 1 Egress is done using the regular operating mode of the resources of local government and non-government authorities. Level 2 Egress of the City overwhelms the capacity of the regular operating mode of the resources of local entities. At this level, the Disaster Management Unit (DMU) of the POSC will take control of the egress process through its Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). -

Identification and Remediation of Water-Quality Hotspots in Havana

J.J. Iudicello et al.: Identification and Remediation of Water-Quality Hotspots in Havana, Cuba 72 ISSN 0511-5728 The West Indian Journal of Engineering Vol.35, No.2, January 2013, pp.72-82 Identification and Remediation of Water-Quality Hotspots in Havana, Cuba: Accounting for Limited Data and High Uncertainty Jeffrey J. Iudicelloa Ψ, Dylan A. Battermanb, Matthew M. Pollardc, Cameron Q. Scheidd, e and David A. Chin Department of Civil, Architectural, and Environmental Engineering, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA a E-mail: [email protected] b E-mail: [email protected] c E-mail: [email protected] d E-mail: [email protected] e E-mail: [email protected] Ψ Corresponding Author (Received 19 May 2012; Revised 26 November 2012; Accepted 01 January 2013) Abstract: A team at the University of Miami (UM) developed a water-quality model to link in-stream concentrations with land uses in the Almendares River watershed, Cuba. Since necessary data in Cuba is rare or nonexistent, water- quality standards, pollutant data, and stormwater management data from the state of Florida were used, an approach justified by the highly correlated meteorological patterns between South Florida and Havana. A GIS platform was used to delineate the watershed and sub-watersheds and breakdown the watershed into urban and non-urban land uses. The UM model provides a relative assessment of which river junctions were most likely to exceed water-quality standards, and can model water-quality improvements upon application of appropriate remediation strategies. The pollutants considered were TN, TP, BOD5, fecal coliform, Pb, Cu, Zn, and Cd. -

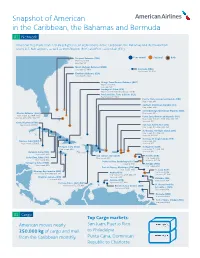

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

Preserving What? Design Strategies for a Post-Revolutionary Cuba

Preserving What? Design Strategies for a Post-Revolutionary Cuba JAYASHREE SHAMANNA & GABRIEL FUENTES Marywood University The Cuban Revolution’s neglect of Havana (as part of urban fabric? What role does preservation play? For a broader socialist project) simultaneously ruined and that matter, what does preservation really mean and preserved its architectural and urban fabric. On one by what criteria are sites included in the preservation hand, Havana is crumbling, its fifty-plus year lack of frame? What relationships are there (or could there maintenance inscribed on its cracked, decayed sur- be) between preservation, tourism, infrastructure, faces and the voids where buildings once stood; on education, housing, and public space? the other, its formal urban fabric—its scale, dimen- In the process, students established systematic sions, proportions, contrasts, continuities, solid/ research agendas to reveal opportunities for inte- void relationships, rhythms, public spaces, and land- grated “soft” and “hard” interventions (i.e. siting and scapes—remain intact. A free-market Cuba, while programing), constructing ecologies across a range inevitable, leaves the city vulnerable to unsustain- of disciplinary territories including (but not limited able urban development. And while many anticipate to): architecture, urban design, historic preservation preservation, restoration, and urban development— / restoration, art, landscape urbanism, infrastruc- particularly of Havana’s historic core (La Habana ture, science + technology, economics, sustainability, -

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1 Louisiana Historical Background 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 •Spain sides with France in the now expanded Seven Years War •The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement of 1762 in which France ceded Louisiana (New France) to Spain. •Spain acquires Louisiana Territory from France 1763 •No troops or officials for several years •The colonists in western Louisiana did not accept the transition, and expelled the first Spanish governor in the Rebellion of 1768. Alejandro O'Reilly suppressed the rebellion and formally raised the Spanish flag in 1769. Antonio de Ulloa Alejandro O'Reilly 1763 – 1770 1763 – 1770 •France’s secret treaty contained provisions to acquire the western Louisiana from Spain in the future. •Spain didn’t really have much interest since there wasn’t any precious metal compared to the rest of the South America and Louisiana was a financial burden to the French for so long. •British obtains all of Florida, including areas north of Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Maurepas and Bayou Manchac. •British built star-shaped sixgun fort, built in 1764, to guard the northern side of Bayou Manchac. •Bayou Manchac was an alternate route to Baton Rouge from the Gulf bypassing French controlled New Orleans. •After Britain acquired eastern Louisiana, by 1770, Spain became weary of the British encroaching upon it’s new territory west of the Mississippi. •Spain needed a way to populate it’s new territory and defend it. •Since Spain was allied with France, and because of the Treaty of Allegiance in 1778, Spain found itself allied with the Americans during their independence. -

A Family Program in Cuba December 27, 2019 - January 1 , 2020

NEW YEAR’S IN HAVANA: A FAMILY PROGRAM IN CUBA DECEMBER 27, 2019 - JANUARY 1 , 2020 As diplomatic and economic ties between the United States and Cuba are reformed over the next few years, the landscape of Cuba will dramatically change, making it more important than ever to experience Cuba as it is today. On this family-friendly program to Havana, experience a variety of Cuban art, music, and dance with activities aimed at all ages. Enjoy playing a baseball game with Cubans close to Hemingway’s favorite hang-out in Cojimar. Dine at some of the most popular paladares, private restaurants run by Cuban entrepreneurs—often in family homes. Learn about the nation’s history and economic structure, and discuss the reforms driving changes with your Harvard study leader and local guest speakers. Learn how to salsa in a private class—and much more! The Harvard Alumni Association is operating this educational program under the General License authorized by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). This program differs from more traditional trips in that every hour must be accounted for. Each day has been structured to provide meaningful interactions with Cuban people or educational or cultural programming. Please note that Harvard University intends to fully comply with all requirements of the General License. Travelers must participate in all group activities. GROUP SIZE: Up to 30 guests PRICING: To be announced STUDY LEADER: To be announced Enjoy lunch at La Moneda Cubana, a roof-top SCHEDULE BY DAY paladar in the heart of Old Havana. B=Breakfast, L=Lunch, D=Dinner After lunch, stop at Los Clandestina, which was founded by young Cuban artists and entrepreneurs, Clandestina is Cuba’s first FRIDAY, DECEMBER 27 design store—providing both tourists and MIAMI / HAVANA residents with contemporary products that are uniquely designed and manufactured in Independent arrivals in Havana. -

Status of Cuban Coral Reefs

Bull Mar Sci. 94(2):229–247. 2018 research paper https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2017.1035 Status of Cuban coral reefs 1 Centro de Investigaciones Patricia González-Díaz 1 * Marinas, Universidad de 2, 3 La Habana, Calle 16 No. 114, Gaspar González-Sansón Miramar, Playa, Havana 11300, Consuelo Aguilar Betancourt 2, 3 Cuba. Sergio Álvarez Fernández 1 2 Departamento de Estudios Orlando Perera Pérez 1 para el Desarrollo Sustentable 1 de la Zona Costera, Universidad Leslie Hernández Fernández de Guadalajara, Gómez Farías 82, Víctor Manuel Ferrer Rodríguez 1 San Patricio-Melaque, Cihuatlán, Yenisey Cabrales Caballero 1 Jalisco, CP 48980, Mexico. 1 3 Maickel Armenteros Canadian Rivers Institute, 100 1 Tucker Park Rd, Saint John, NB Elena de la Guardia Llanso E2L 4A6, Canada. * Corresponding author email: <[email protected]>. ABSTRACT.—Cuban coral reefs have been called the “crown jewels of the Caribbean Sea,” but there are few comparative data to validate this claim. Here, we provide an overview of Cuban coral reefs based on surveys carried out between 2010 and 2016 on seven of the main Cuban coral reef systems: Havana, Artemisa, Los Colorados, Punta Francés, Los Canarreos Archipelago, Península Ancón, and Jardines de la Reina. Ecological indicators were evaluated for each of these areas at the community level. Results suggest differences among benthic communities (corals, sponges, and gorgonians) that are most evident for reefs that develop near highly urbanized areas, such as Havana, than for those far from the coast and less accessible. Offshore reefs along the south-central coast at Jardines de la Reina and Península Ancón exhibited high coral density and diversity. -

Architecture and Preservation in Havana, Cuba a Trip Sponsored Utah Heritage Foundation April 3-9, 2016

Architecture and Preservation in Havana, Cuba A Trip Sponsored Utah Heritage Foundation April 3-9, 2016 Utah Heritage Foundation is pleased to announce its first program in celebration of the organization’s 50th Anniversary in 2016 – Architecture and Preservation in Havana, Cuba. Cuba has often been referred to as a land lost in time. 1957 Chevys still cruise the streets and Havana neighborhoods display building representing over five centuries of rich heritage. The salt, humidity, and hurricanes have no doubt taken their toll on these architectural masterpieces, but time has made it more evident that the buildings are in need of serious repair. The Cuban government has been working diligently to rehabilitate these buildings, but it’s a massive undertaking that’s been made even more difficult due to the U.S. embargo. Historic preservation has become a key strategy and innovative tool for the revitalization and sustainable economic development of distressed urban neighborhoods of Havana and rural areas in Cuba. These examples provide models for the revitalization and sustainable development of urban and rural areas in other economically challenged areas of the world, including the United States. Friday, August 14, 2015 marked the grand reopening ceremony for the U.S. embassy in Havana. Progress in normalizing relations with Cuba is quickly being made and changes to the landscape are inevitable. Although only ninety miles of ocean separate us from Havana, it sometimes feels like we are worlds apart. However, we can find commonality with the Cuban people through our desire to preserve our architectural legacy. What will the progress between Washington, D.C. -

Havana XIII Biennial Tour 2 - Vip Art Tour 7 Days/ 6 Nights

Havana XIII Biennial Tour 2 - Vip Art Tour 7 Days/ 6 Nights Tour Dates: Friday, April 12th to Thursday, April 19th Friday, April 19th to Thursday, April 25th Group Size: Limit 10 people Itinerary Day 1 – Friday - Depart at 9:20 am from Miami International Airport in Delta Airline flight DL 650, arriving in Havana at 10:20 am. After clearing immigrations and customs, you will be greeted at the airport and driven to your Hotel. Check-in and relax and get ready for the adventure of a life time. Experience your first glimpse of the magic of Cuba when a fleet of Classic Convertibles American Cars picks up the group before sundown for an unforgettable tour of Havana along the Malecón, Havana’s iconic seawall, that during the Biennale turns into an interactive art gallery. The tour will end across the street of The Hotel Nacional at Restaurant Monseigneur, for Welcome Cocktails and Dinner. You will be able to interact with Cuban artists and musicians that will be invited to join the group and engage in friendly discussion about Cuban culture and art all the time listening to live Cuban music from yesterday. (D) Day 2 – Saturday - Walking tour of the Old City. Old Havana is truly a privileged place for art during the Biennale. During our walking tour we will wander through the four squares, Plaza de Armas, Plaza de San Francisco, Plaza Vieja, and Plaza de la Catedral de San Cristóbal de La Habana, and view the vast array of art exhibits and performance art that will be taking place at the Wifredo Lam Contemporary Art Center, and other stablished venues, such as El Taller Experimental de Gráfica, the Center for the Development of Visuals Arts, and La Fototeca. -

8 Day Cuba Program for Stetson - January 3-10, 2015

8 DAY CUBA PROGRAM FOR STETSON - JANUARY 3-10, 2015 - Participants should know that Cuba is a special destination, and so please understand that all elements of this itinerary are subject to change and that times and activities listed below are approximate. Please remain flexible as there are often circumstances beyond our control and changes may be necessary. The tour leader reserves the right to make changes to the published itinerary whenever, in his sole discretion, conditions warrant, or if he deems it necessary for the comfort or safety of the program. Be assured that all efforts will be made to provide a comparable alternative should an item on the itinerary need to be changed or cancelled. Program includes: ● Airfare to Havana (HAV), Cuba, either from Tampa (TPA) or Miami (MIA). ● Medical insurance while in Cuba. ● 7 nights hotel accommodations at the Inglaterra Hotel, well located, Old Havana. ● Breakfast daily (B), 4 lunches (L) and 2 dinners (D). ● English-speaking guide and private bus transfers for certain program activities. ● Daily people-to-people exchanges with local Cubans. ● Day trip to the UNESCO World Heritage site of the Viñales Valley in the west. ● All items mentioned in tour below. (subject to change) Items mentioned below in ALL CAPS are included in your program fee HOTEL INGLATERRA in Old Havana-Hotel Inglaterra, of 4 stars category, is one of the most classic hotels in Havana. Hotel Inglaterra, considered the doyen of the tourist establishments of the island of Cuba, is located on Paseo del Prado Ave. #416 between San Rafael and San Miguel Streets, Old Havana, City of Havana, Cuba.