Collected Contributions of Invited Lecturers and Authors to the 10C/FAO/U N EP International Workshop on Marine Pollution in the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961

Nikolaus Böttcher Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961 In the late afternoon of 4 March 1762 the British war fleet left the port of Spithead near Portsmouth with the order to attack and conquer “the Havanah”, Spain’s main port in the Caribbean. The decision for the conquest was taken after the new Spanish King, Charles III, had signed the Bourbon family pact with France in the summer of 1761. George III declared war on Spain on 2 January of the following year. The initiative for the campaign against Havana had been promoted by the British Prime Minister William Pitt, the idea, however, was not new. During the “long eighteenth century” from the Glorious Revolution to the end of the Napoleonic era Great Britain was in war during 87 out of 127 years. Europe’s history stood under the sign of Britain’s aggres sion and determined struggle for hegemony. The main enemy was France, but Spain became her major ally, after the Bourbons had obtained the Spanish Crown in the War of the Spanish Succession. It was in this period, that America became an arena for the conflict between Spain, France and England for the political leadership in Europe and economic predominance in the colonial markets. In this conflict, Cuba played a decisive role due to its geographic location and commercial significance. To the Spaniards, the island was the “key of the Indies”, which served as the entry to their mainland colonies with their rich resources of precious metals and as the meeting-point for the Spanish homeward-bound fleet. -

City of Port-Of-Spain Mass Egress Plan Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Port-of-Spain (POS), the Capital City of Trinidad and Tobago is located in the county of St. George. It has a residential population of 49,031 and a population density of 4,086. Moreover, it has an average transient population on any given day of 350,000 persons. The Port of Spain Corporation (POSC) is vulnerable to a number of natural, man-made and technological hazards. The list of natural hazards includes, but not limited to, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes and landslides. Chiefly and most frequent among the natural hazards is flooding. When this event occurs, the result is excessive street flooding that inhibits the movement of individuals in and out of the City for approximately two-three hours, until flood waters subside. The intensity of the event is magnified by concurrent high tide. The purpose of the City of Port-of-Spain Mass Egress Plan is to address the safe and strategic movement of the mass number of people from places of danger in POS to areas deemed safe. This plan therefore endeavours to facilitate planned and unplanned egress of persons when severe flooding occurs in the City. Levels of Egress Fundamentally, the City of Port-of-Spain Mass Egress Plan establishes a three-tiered egress process: . Level 1 Egress is done using the regular operating mode of the resources of local government and non-government authorities. Level 2 Egress of the City overwhelms the capacity of the regular operating mode of the resources of local entities. At this level, the Disaster Management Unit (DMU) of the POSC will take control of the egress process through its Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). -

Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua): Patterns of Human Rights Violations

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) independent analysis e-mail: [email protected] CENTRAL AMERICA (GUATEMALA, EL SALVADOR, HONDURAS, NICARAGUA): PATTERNS OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS A Writenet Report by Beatriz Manz (University of California, Berkeley) commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Status Determination and Protection Information Section (DIPS) August 2008 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or UNHCR. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................ iii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 1.1 Regional Historical Background ................................................................1 1.2 Regional Contemporary Background........................................................2 1.3 Contextualized Regional Gang Violence....................................................4 -

Central America and the Bitter Fruit of U.S. Policy by Bill Gentile

CLALS WORKING PAPER SERIES | NO. 23 Central America and the Bitter Fruit of U.S. Policy by Bill Gentile OCTOBER 2019 Pullquote Bill Gentile in Nicaragua in the mid-1980s / Courtesy Bill Gentile Bill Gentile is a Senior Professorial Lecturer and Journalist in Residence at American University’s School of Communication. An independent journalist and documentary filmmaker whose career spans four decades, five continents, and nearly every facet of journalism and mass communication, he is the winner of two national Emmy Awards and was nominated for two others. He is a pioneer of “backpack video journalism” and the director, executive producer, and host of the documentary series FREELANCERS with Bill Gentile. He teaches Photojournalism, Foreign Correspondence, and Backpack Documentary. TheCenter for Latin American & Latino Studies (CLALS) at American University, established in January 2010, is a campus- wide initiative advancing and disseminating state-of-the-art research. The Center’s faculty affiliates and partners are at the forefront of efforts to understand economic development, democratic governance, cultural diversity and change, peace and diplomacy, health, education, and environmental well-being. CLALS generates high-quality, timely analysis on these and other issues in partnership with researchers and practitioners from AU and beyond. A previous version of this piece was published by the Daily Beast as a series, available here. Cover photo: Courtesy Bill Gentile 2 AU CENTER FOR LATIN AMERIcaN & LATINO STUDIES | CHAPTER TITLE HERE Contents -

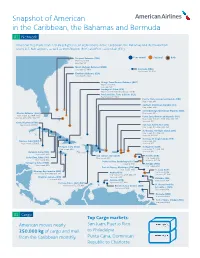

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

Surface Currents Near the Greater and Lesser Antilles

SURFACE CURRENTS NEAR THE GREATER AND LESSER ANTILLES by C.P. DUNCAN rl, S.G. SCHLADOW1'1 and W.G. WILLIAMS SUMMARY The surface flow around the Greater and Lesser Antilles is shown to differ considerably from the widely accepted current system composed of the Caribbean Current and Antilles Current. The most prominent features deduced from dynamic topography are a flow from the north into the Caribbean near Puerto Rico and a permanent eastward-flowing counter-current in the Caribbean itself between Puerto Rico and Venezuela. Noticeably absent is the Antilles Current. A satellite-tracked buoy substantiates the slow southward flow into the Caribbean and the absence of the Antilles Current. INTRODUCTION Pilot Charts for the North Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea (Defense Mapping Agency, 1968) show westerly surface currents to the North and South of Puerto Rico. The Caribbean Current is presented as an uninterrupted flow which passes through the Caribbean Sea, Yucatan Straits, Gulf of Mexico, and Florida Straits to become the Gulf Stream. It is joined off the east coast of Florida by the Antilles Current which is shown as flowing westwards along the north coast of Puerto Rico and then north-westerly along the northern edge of the Bahamas (BOISVERT, 1967). These surface currents are depicted as extensions of the North Equatorial Current and the Guyana Current, and as forming part of the subtropical gyre. As might be expected in the absence of a western boundary, the flow is slow-moving, shallow and broad. This interpretation of the surface currents is also presented by WUST (1964) who employs the same set of ship’s drift observations as are used in the Pilot Charts. -

Caribbean Current Variability and the Influence of the Amazon And

ARTICLE IN PRESS Deep-Sea Research I 54 (2007) 1451–1473 www.elsevier.com/locate/dsri Caribbean current variability and the influence of the Amazon and Orinoco freshwater plumes L.M. Che´rubina,Ã, P.L. Richardsonb aRosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, FL 33149 Miami, USA bDepartment of Physical Oceanography, MS 29, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 360 Woods Hole Road, Woods Hole, MA 0254, USA Received 5 February 2006; received in revised form 16 April 2007; accepted 24 April 2007 Available online 18 May 2007 Abstract The variability of the Caribbean Current is studied in terms of the influence on its dynamics of the freshwater inflow from the Orinoco and Amazon rivers. Sea-surface salinity maps of the eastern Caribbean and SeaWiFS color images show that a freshwater plume from the Orinoco and Amazon Rivers extends seasonally northwestward across the Caribbean basin, from August to November, 3–4 months after the peak of the seasonal rains in northeastern South America. The plume is sustained by two main inflows from the North Brazil Current and its current rings. The southern inflow enters the Caribbean Sea south of Grenada Island and becomes the main branch of the Caribbean Current in the southern Caribbean. The northern inflow (141N) passes northward around the Grenadine Islands and St. Vincent. As North Brazil Current rings stall and decay east of the Lesser Antilles, between 141N and 181N, they release freshwater into the northern part of the eastern Caribbean Sea merging with inflow from the North Equatorial Current. Velocity vectors derived from surface drifters in the eastern Caribbean indicate three westward flowing jets: (1) the southern and fastest at 111N; (2) the center and second fastest at 141N; (3) the northern and slowest at 171N. -

A Tale of Twenty Cities a Tale of Twenty Cities

NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES CHICAGO, ILLINOIS NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES DENVER, COLORADO NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES DETROIT, MICHIGAN NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES GUADALAJARA, MEXICO NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES HAVANA, CUBA (MARKED ON MAP AS LA HABANA) NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES HOUSTON, TEXAS NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES MANAGUA, NICARAGUA NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES MEXICO CITY, MEXICO (IDENTIFIED ON MAP AS MEXICO) NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES MONTERREY, MEXICO NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES MONTREAL, QUEBEC NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES NEW YORK CITY, NEW YORK NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES PHOENIX, ARIZONA NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES PUEBLA, MEXICO NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES SAINT DOMINGO, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA NORTH AMERICA A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES A TALE OF TWENTY CITIES ST. -

Chikungunya Virus Outbreak in Sint Maarten, 2013–2014

SPECIAL ISSUE ON CHIKUNGUNYA IN THE REGION OF THE AMERICAS Pan American Journal Brief communication of Public Health Chikungunya virus outbreak in Sint Maarten, 2013–2014 Maria Henry,1 Lorraine Francis,2 Virginia Asin,1 Karen Polson-Edwards,2 and Babatunde Olowokure2 Suggested citation Henry M, Francis L, Asin V, Polson-Edwards K, Olowokure B. Chikungunya virus outbreak in Sint Maarten, 2013–2014. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e61. ABSTRACT This report describes the outbreak of chikungunya virus (CHIKV) in Sint Maarten, a con- stituent country of Kingdom of the Netherlands comprising the southern part of the Caribbean island of Saint Martin, from 22 December 2013 (first reported case) through 5 December 2014. The outbreak was first reported by the French overseas collectivity of Saint-Martin in the northern part of the island—the first site in the Americas to report autochthonous transmission of CHIKV. By 5 December 2014, Sint Maarten had reported a total of 658 cases—an overall attack rate of 1.76%. Actual prevalence may have been higher, as some cases may have been misdiagnosed as dengue. Fever and arthralgia affected 71% and 69% of reported cases respectively. Of the 390 laboratory-confirmed cases, 61% were female and the majority were 20–59 years old (mean: 42; range: 4–92). The spread of CHIKV to Sint Maarten was inevitable given the ease of movement of people, and the vector, island-wide. Continuing their history of collaboration, the French and Dutch parts of the island coordinated efforts for prevention and control of the disease. -

Development and Implementation of Sargassum Early Advisory System (SEAS)

Development and implementation of Sargassum Early Advisory System (SEAS) By Robert K. Webster Ph.D. candidate, Marine Sciences Department [email protected] Dr. Tom Linton Professor, Marine Science Department [email protected] Texas A&M University at Galveston, P.O. Box 1675, Galveston, Texas 77553 ABSTRACT hardship, since their annual budgets have little or no room for The Texas Gulf Coast consists of 367 miles of coastline, unforeseen expenditures. To assist beach management efforts, primarily sandy beaches. The slight slope of these beaches scientists at Texas A&M University at Galveston have been creates many large expanses of beach where the public can investigating the use of satellite imagery to forecast Sargas- enjoy a variety of activities such as beach combing, surfing, sum landings along the Texas coastline. This Sargassum Early swimming, and surf fishing. Communities that manage these Advisory System (SEAS) is designed to give coastal managers areas rely heavily on tourism as a primary source of income. as much warning as possible, allowing them to adjust their Texas beach tourism generates approximately $7 billion per allocation of resources for the management of Sargassum year, according to the Texas General Land Office’s (TGLO) landings. SEAS model uses satellite imagery from Landsat website (http://www.glo.texas.gov). Public use of these beaches Data Continuity Mission (LANDSAT) satellites to track the can be severely restricted by the periodic mass landings of movement of Sargassum as it approaches each sector along the free-floating plant Sargassum, commonly referred to as the Texas Gulf Coast. During 2012, a total of 38 advisories seaweed. -

Doug Wilson C/O NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office, 410 Severn Avenue

2.4 THE NOPP YEAR OF THE OCEAN DRIFTER PROGRAM Doug Wilson NOAA/AOML, Miami, FL organize themselves until they approach the 1. INTRODUCTION Yucatan Channel, where they form into a coherent northward flow known as the Yucatan Current. Beginning in March of 1998, over 150 WOCE Once through the Yucatan Channel, the flow type drifting buoys, drogued at 15 meters depth, were launched in the Gulf of Mexico and the becomes the Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico Caribbean Sea and their approaches, providing in and then the Florida Current east of the excess of 30,000 drifter days of data to date. southeastern U.S. coast. The manner in which Buoys were provided by the U.S. National Ocean these warm western Atlantic and Caribbean currents organize into the powerful Florida Current / Partnership Program; launch co-ordination was provided by NOAA and academic research Gulf Stream system is not well understood. scientists interested in regional ocean circulation studies; and logistical and data processing support The Caribbean Sea is also the location of some was provided by the NOAA/AOML Global Drifter of the richest coastal and reef habitats in the tropical oceans. As the Caribbean Current flows and Data Assembly Centers. Buoys were launched with the cooperation of commercial ships, the westward on its way to the Yucatan Peninsula, it Colombian Navy, the U.S. Coast Guard, and passes through very productive zones of coastal research vessels working in the region. Drifter track upwelling (produced by the easterly winds) north of figures and data have been made available in real Venezuela and Colombia, fertile coastal "nurseries" and estuaries such as the Cienaga Grande de time via the WWW at www.IASlinks.org and www.drifters.doe.gov. -

Drugs, Consumption, and Primitive Accumulation in Managua, Nicaragua

1 Working Paper no.71 URBAN SEGREGATION FROM BELOW: DRUGS, CONSUMPTION, AND PRIMITIVE ACCUMULATION IN MANAGUA, NICARAGUA Dennis Rodgers Crisis States Research Centre October 2005 Copyright © Dennis Rodgers, 2005 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. 1 Crisis States Research Centre Urban segregation from below: Drugs, Consumption, and Primitive Accumulation in Managua, Nicaragua Dennis Rodgers Crisis States Research Centre Introduction This paper explores the emergence of new forms of urban segregation in contemporary Managua, Nicaragua. Although the country has historically always been characterised by high levels of socio-economic inequality – with the notable exception of the Sandinista revolutionary period (1979-90), when disparities declined markedly – the past decade in particular has seen the development of new processes of exclusion and differentiation, especially in urban areas. In many ways, these are part of a broader regional trend; as several recent studies have noted, many other Latin American cities are undergoing similar mutations.