The Continuing Quest for Self-Determination | | Postguam.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Status and External Affairs Subcommittee Transition Report

Political Status and External Affairs Subcommittee Transition Report The report for the Political Status and External Affairs Subcommittee for the incoming Calvo- Tenorio Administration has been divided into two sections. The first section addresses the Commission on Decolonization and the Political Status issue for Guam, and the second section addresses the issues related to External Affairs. I. Political Status Overall Description or Mission of Department/Agency The Commission on Decolonization created by Public Law 23-147 has been inactive for a number of years. The legislation creating the Commission was enacted by I Mina’ Benti Tres na Liheslaturan Guåhan, notwithstanding the objections of the Governor, mandated the creation of a Commission on Decolonization. (PL 23-147 was overridden with sixteen (16) affirmative votes (including those of current Speaker Judi Won Pat, Senators Tom C. Ada and Vicente C. Pangelinan – incumbent Senators who have successfully retained their seats for I Mina’ Trentai Uno na Liheslaturan Guåhan.) Public Law 23-147 constitutes the Commission on Decolonization and mandates that those appointed will hold their seats on the Commission for the life of the Commission. The individuals last holding seats on the Commission are: 1. Governor Felix P. Camacho, who relinquishes his seat and Chairmanship upon the inauguration of Governor-Elect Eddie B. Calvo. 2. Speaker Judith T. Won Pat, who retains her seat as Speaker of I Mina’ Trentai Uno na Liheslaturan Guåhan or, may appoint a Senator to fill her seat. 3. Senator Eddie B. Calvo, who relinquishes his seat upon inauguration as Governor and assumption of the Chairmanship of the Commission. -

Antonio Borja Won Pat 19 08–1987

H former members 1957–1992 H Antonio Borja Won Pat 19 08–1987 DELEGATE 1973–1985 DEMOCRAT FROM GUAM he son of an immigrant from Hong Kong, at the Maxwell School in Sumay, where he worked until Antonio Borja Won Pat’s long political career 1940. He was teaching at George Washington High School culminated in his election as the first Territorial when Japan invaded Guam in December 1941. Following TDelegate from Guam—where “America’s day begins,” a the war, Won Pat left teaching and organized the Guam reference to the small, Pacific island’s location across the Commercial Corporation, a group of wholesale and retail international dateline. Known as “Pat” on Guam and sellers. In his new career as a businessman, he became “Tony” among his congressional colleagues, Won Pat’s president of the Guam Junior Chamber of Commerce. small-in-stature and soft-spoken nature belied his ability Won Pat’s political career also pre-dated the Second to craft alliances with powerful House Democrats and use World War. He was elected to the advisory Guam congress his committee work to guide federal money towards and in 1936 and served until it was disbanded when war protect local interests in Guam.1 It was these skills and broke out. After the war, Won Pat helped organize the his close relationship with Phillip Burton of California, a Commercial Party of Guam—the island’s first political powerful figure on the House Interior and Insular Affairs party. Won Pat served as speaker of the first Guam Committee, that helped Won Pat become the first Territorial Assembly in 1948 and was re-elected to the post four Delegate to chair a subcommittee. -

Download This Volume

Photograph by Carim Yanoria Nåna by Kisha Borja-Quichocho Like the tåsa and haligi of the ancient Chamoru latte stone so, too, does your body maintain the shape of the healthy Chamoru woman. With those full-figured hips features delivered through natural birth for generations and with those powerful arms reaching for the past calling on our mañaina you have remained strong throughout the years continuously inspire me to live my culture allow me to grow into a young Chamoru woman myself. Through you I have witnessed the persistence and endurance of my ancestors who never failed in constructing a latte. I gima` taotao mo`na the house of the ancient people. Hågu i acho` latte-ku. You are my latte stone. The latte stone (acho` latte) was once the foundation of Chamoru homes in the Mariana Islands. It was carved out of limestone or basalt and varied in size, measuring between three and sixteen feet in height. It contained two parts, the tasa (a cup-like shape, the top portion of the latte) and the haligi (the bottom pillar) and were organized into two rows, with three to seven latte stones per row. Today, several latte stones still stand, and there are also many remnants of them throughout the Marianas. Though Chamorus no longer use latte stones as the foundations of their homes, the latte symbolize the strength of the Chamorus and their culture as well as their resiliency in times of change. Micronesian Educator Editor: Unaisi Nabobo-Baba Special Edition Guest Editors: Michael Lujan Bevacqua Victoria Lola Leon Guerrero Editorial Board: Donald Rubinstein Christopher Schreiner Editorial Assistants: Matthew Raymundo Carim Yanoria Design and Layout: Pascual Olivares ISSN 1061-088x Published by: The School of Education, University of Guam UOG Station, Mangilao, Guam 96923 Contents Guest Editor’s Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

Guam Time Line

Recent Timeline of Coral Reef Management in Guam Developed in Partnership with Guam J-CAT Disclaimer The EPA Declares the Military's The purpose of this timeline is to present a simplifying visual- Expansion Policy "Environmentally Unsatisfactory" and Halts Develop- ment ization of the events that may have inucend the development The US recently proposed plans to expand US Return to Liberate Guam as a military operations in Guam, by adding a new Military Stronghold base, airfield, and facilities to support 80,000 of capacity to manage coral reefs in Guam over time. 1944 new residents. Dredging the port alone will require moving 300,000 square meters of During the occupation, the people of Guam GUAM-Air Force Begins Urunao coral reef. In February 2010, the U.S. Envi- were subjected to acts that included torture, US Military buildup in Guam is Dump Site ronmental Protection Agency rated the plan beheadings and rape, and were forced to as "Environmentally Unsatisfactory" and reduced Air Force begins cleanup of the formerly used adopt the Japanese culture. Guam was suggested revisions to upgrade wastewater The investment price decreased from $10.27 Urunao dumpsite at Andersen Air Force Base By its nature, it is incomplete. For example, the start date is subject to fierce fighting when U.S. troops treatment systems and lessen the proposed billion to 8.6 billion; marine transfers on the northern end of Guam. recaptured the island on July 21, 1944, a date port's impact on the reef. decreased from 8600 to 5000 commemorated every year as Liberation Day. -

Frank Leon Guerrero/Democrat

FRANK LEON GUERRERO/DEMOCRAT QUESTIONNAIRE The deadline to submit written answers is September 30th, 2020 Legislative Candidate Interview Vying For Election To The 36th Guam Legislature A. Real Estate Industry Related 1. The Governor’s office has upgraded the classification of the real estate industry as an essential service during COVID-19 “Condition of Readiness” operating restrictions. However, the Government of Guam agencies that are part and parcel of the real estate industry remain either closed or inactive. (The real estate industry encompasses private sector real estate activities as well as Government of Guam agencies that are involved in the processing of real estate transactions including taxation, recordation, land management interaction, construction and land use permitting, building inspections, building occupancy, and document recordation.). Will you support the preparation and passage of legislation to classify the whole of the real estate industry encompassing both the private sector and related Government of Guam agencies as TRUE ESSENTIAL SERVICES? While I am aware of their being a distinction between “essential services” and “true essential services”. This crisis has forced the awareness of being able to operate the government by implementing a complete digital transformation of distinction government. In many communities across the country obtaining a mortgage and buying a home are processed entirely online. If elected I will work closely with the Association on legislation that will address these concerns. Real Estate is a critical part of our locally grown economy. 2. The Guam Land Use Commission (GLUC) application processing system has been rendered inactive by GovGuam COVID restrictions since March 2020 with no apparent urgency to restore the system to full operation. -

Joakim Peter Guam

196 the contemporary pacific • spring 2000 gress also reelected Congressman Jack ruled in favor of the national govern- Fritz as its Speaker, Congressman ment, and the states were already Claude Phillip as vice speaker, and making plans to appeal the case. In Senator Joeseph Urusemal of Yap as the meantime, the issue did not get the new floor leader. A special elec- the necessary support from voters in tion was held in July 1999 to fill the the July elections. Given these results, vacant senate seats from Pohnpei and the fate of the court appeal is unclear. Chuuk. In the special election, Resio Furthermore, in relation to the second Moses, Pohnpei, and Manny Mori, proposed amendment defeated by Chuuk, were elected to Congress. voters, the Congress passed a law, By act of petition, three amend- effective 1 October 1998, which ments to the FSM Constitution were increases the states’ share of revenue put on the ballot during the general to 70 percent! elections. The amendments center joakim peter around the issues of revenue sharing and ownership of resources. One of the challenges to national unity in Guam the FSM will always be the issue of resources, especially since one of the Although Guam came through unique features of the federation is 1998–99 without a punishing the weaker national government that typhoon, President Clinton hit Guam allows the state governments more like a storm, as did the November flexibility and power. The first pro- general elections, Chinese illegal posal is to amend section 2 of Article entrants, and the effort to restructure I (Territory of Micronesia) to basi- Guam’s school system. -

LEG 18-0021 Fax: 477-4703 !Aw@~Amag.Org TO: the Honorable Regine Biscoe Lee Jacqueline Z

Office of the Attorney General of Guam 590 S. Marine Corps Dr., Ste. 901, Tamuning, Guam 96913 January 19, 2018 Elizabeth Barrett-Anderson Attorney General Phone: (671) 475-3324 ext 5015/ 5030 OPINION MEMORANDUM Ref: LEG 18-0021 Fax: 477-4703 !aw@~amag.org TO: The Honorable Regine Biscoe Lee Jacqueline Z. Cruz Legislative Secretary Chief of Staff I Mina 'Trentai Kudtro Na Liheslaturan Gudhan Administration ext. 5010 34th Guam Legislature [email protected] FROM: Attorney General Joseph B. McDonald Chief Prosecutor Prosecution SUBJECT: Legal Opinion Regarding the Application of 3 GCA § 16311 which ext 2410 Requires a Voter Referendum Before Increases in Taxes May Be [email protected] Established, to Bill 230-34 (LS) which would Repeal Tax Exemptions Karl P. Espaldon for Qualifying Insurance, Wholesale, and Banking Companies. Deputy AG Solicitors This Office is in receipt of your request for a legal opinion dated January 11 , 2018 ext 3115 [email protected] seeking clarification as to whether Bill 230-34 (LS), which proposes to repeal tax exemptions for qualifying insurance, wholesale, and banking companies, would trigger Kenneth D. Orcutt the voter referendum requirement found at 3 GCA § 16311. You note that the Deputy AG Litigation Legislature already has proposals similar to Bill 230-34 (LS) that may remove tax ext 3225 exemptions in order to raise revenue from currently exempted businesses. [email protected] Fred S. Nishihira Introduction Deputy AG Consumer Protection This Office has just recently answered a very similar request from Senator Thomas C. ext 3250 Ada, Chairman of the Committee on Environment, Land, Agriculture and Procurement [email protected] Reform, asking whether contemplated increases in the Realty Conveyance Tax located Rebecca M. -

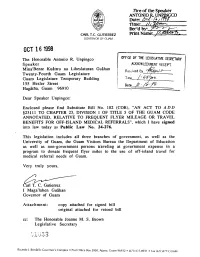

OCT 16 1998 - the Honorable Antonio R

CARL T.C. GUTIERREZ GOVERNOR OF GUAM OCT 16 1998 - The Honorable Antonio R. Unpingco OFFICE OF THE LEGISLATIVE SECRETARY Speaker Mina'Bente KuBttro na Liheslaturan Guihan Rec,rved Ey Twenty-Fourth Guam Legislature Guam Legislature Temporary Building 155 Hesler Street I Hagitiia, Guam 96910 - Dear Speaker Unpingco: Enclosed please find Substitute Bill No. 182 (COR), "AN ACT TO ADD $231 11 TO CHAPTER 23, DIVISION 1 OF TITLE 5 OF THE GUAM CODE ANNOTATED, RELATIVE TO FREQUENT FLYER MILEAGE OR TRAVEL BENEFITS FOR OFF-ISLAND MEDICAL REFERRALS", which I have signed into law today as Public Law No. 24-276. This legislation includes all three branches of government, as well as the University of Guam, the Guam Visitors Bureau the Department of Education as well as non-government persons traveling at government expense in a program to donate frequent flyer miles to the use of off-island travel for medical referral needs of Guam. Veryw truly yours, Carl T. C. Gutierrez I Maga'lahen Guihan Governor of Guam Attachment: copy attached for signed bill original attached for vetoed bill cc: The Honorable Joanne M. S. Brown Legislative Secretary Ricardo I. Bordallo Governor's Complex Posl Office Box 2950, Agana, Guam 96932 (671)472-8931 .fax (6711477-ClJAM MINA'BENTE KUATTRO NA LIHESLATLJRAN GUAHAN 1998 (SECOND) Regular Session CERTIFICATION OF PASSAGE OF AN ACT TO I MAGA'LAHEN GUAHAN This is to certify that Substitute Bill No. 182 (COR), "AN ACT TO ADD 523111 TO CHAPTER 23, DMSION 1 OF TITLE 5 OF THE GUAM CODE ANNOTATED, RELATIVE TO FREQUENT FLYER MILEAGE OR TRAVEL BENEFITS FOR OFF-ISLAND MEDICAL REFERRALS," was on the 2nd day of October, 1998, duly and regularly passed. -

Hearing on H.R. 100, H.R. 2370, and S. 210 Hearing

HEARING ON H.R. 100, H.R. 2370, AND S. 210 HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 100 GUAM COMMONWEALTH ACT, TO ESTABLISH THE COMMONWEALTH OF GUAM, AND FOR OTHER PUR- POSES H.R. 2370 GUAM JUDICIAL EMPOWERMENT ACT OF 1997, TO AMEND THE ORGANIC ACT OF GUAM FOR THE PUR- POSES OF CLARIFYING THE LOCAL JUDICIAL STRUCTURE AND THE OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GEN- ERAL S. 210 TO AMEND THE ORGANIC ACT OF GUAM, THE RE- VISED ORGANIC ACT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS, AND THE COMPACT OF FREE ASSOCIATION ACT, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES OCTOBER 29, 1997, WASHINGTON, DC. Serial No. 105±78 Printed for the use of the Committee on Resources ( COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES DON YOUNG, Alaska, Chairman W.J. (BILLY) TAUZIN, Louisiana GEORGE MILLER, California JAMES V. HANSEN, Utah EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts JIM SAXTON, New Jersey NICK J. RAHALL II, West Virginia ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRUCE F. VENTO, Minnesota JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee DALE E. KILDEE, Michigan JOEL HEFLEY, Colorado PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon JOHN T. DOOLITTLE, California ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American WAYNE T. GILCHREST, Maryland Samoa KEN CALVERT, California NEIL ABERCROMBIE, Hawaii RICHARD W. POMBO, California SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Texas BARBARA CUBIN, Wyoming OWEN B. PICKETT, Virginia HELEN CHENOWETH, Idaho FRANK PALLONE, JR., New Jersey LINDA SMITH, Washington CALVIN M. DOOLEY, California GEORGE P. RADANOVICH, California CARLOS A. ROMERO-BARCELOÂ , Puerto WALTER B. JONES, JR., North Carolina Rico WILLIAM M. (MAC) THORNBERRY, Texas MAURICE D. HINCHEY, New York JOHN SHADEGG, Arizona ROBERT A. -

Guam ·Smashup Claims Variety News Staff by Zaldy Dandan Marianas Agupa Enterpises, Inc

-LJNIVER$/TY OF HAWAII LIBRARY FAA places Saipan 902 suspension airport on 'Alert-3' By Aldwin R. Fajardo Variety News Staff PASSENGERS originating offends Cohen from countries associated with extremist groups will have a hard to Saipan before the meeting. time entering the Saipan Inter "He [Cohen] stressed that the national Airport, after the Com CNMI is missing out on an oppor mon weal th Ports Authority tunity to exchange views about placed the facility on "alert Ievel- goals and objectives in these 3." [minimum wage, immigration and Carlos H. Salas, Ports Author transshipment] issues," Willens ity executi~e director, said said in a correspondence to people originating from places Sablan. · or whose ethnic background is According to him, the .federal Carlos H. Salas associated with terrorists are representative to the 902 talks re considered "high risk" and will international airport_ on alert jected the analogy to pending liti thus be placed under strict moni Ievel-3 following recent bomb gation, stressing that legislative toring. ings of American embassies in proposals are always subject to He, however, immediately Kenya and Tazmania. Jesus R. Sablan political pressures and compro Howard P. Willens explained that this is not meant The last time CPA placed the mise. to di·scriminate but to adopt pre · airport on alert level-3 was after By Aldwin R. Fajardo yer Howard P. Willens indicated Willens said Cohen, during their ventive measures against any the Oklahoma bombing in I 995 Variety News Staff that Cohen was "stunned and meeting, showed clear indication possible attacks by extremists when airport security was strictly THECOMMONWEALTH'sde dumbfounded" when he received that he was upset and that his who are out tc;> sow terror. -

Resolution No. 368-35 (LS)

I MINA'TRENTAI SINGKO NA LIHESLATURAN GUÅHAN RESOLUTIONS PUBLIC DATE Resolution No. Sponsor Title Date Intro Date of Presentation Date Adopted Date Referred Referred to HEARING COMMITTEE NOTES DATE REPORT FILED Committee on Rules Relative to providing I Liheslaturan Guåhan ’s notice to Bank of Guam, to exercise the 8/25/20 8/27/20 Exhibits 1 and 2 option to extend the Maturity Date of the Credit Agreementfor the Guam Congress Building, 6:02 p.m. 4:05 p.m. 368-35 (LS) executed during the 32nd Guam Legislature pursuant to Public Law No. 32-067. Intro/Ref/History LOG 9/3/2020 9:20 AM I MINA′TRENTAI SINGKO NA LIHESLATURAN GUÅHAN 2020 (SECOND) Regular Session Resolution No. 368-35 (LS) Introduced by: Committee on Rules Relative to providing I Liheslaturan Guåhan’s notice to Bank of Guam, to exercise the option to extend the Maturity Date of the Credit Agreement for the Guam Congress Building, executed during the 32nd Guam Legislature pursuant to Public Law No. 32-067. 1 BE IT RESOLVED BY THE COMMITTEE ON RULES OF I 2 MINA′TRENTAI SINGKO NA LIHESLATURAN GUÅHAN: 3 WHEREAS, in 1947, the United States Navy began construction of the Guam 4 Legislature Building, originally known as the “Guam Congress Building”; and 5 WHEREAS, the building was completed on July 8, 1948, and on July 21, 1948, 6 was presented to the people of Guam by Rear Admiral Charles A. Pownall, Naval 7 Governor of Guam; and 8 WHEREAS, the unicameral Guam Legislature, created by the Organic Act to 9 replace the Guam Congress, took over what has come to be known, and hereinafter -

Dissertation Final Format August 2015

Wayreading Chamorro Literature from Guam By Craig Santos Perez A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies In the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Beth Piatote, Chair Professor Elizabeth DeLoughrey Professor Thomas J. Biolsi Professor Hertha D. Wong Summer 2015 © Copyright Craig Santos Perez 2015 Abstract Wayreading Chamorro Literature from Guam by Craig Santos Perez Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Beth Piatote, Chair This dissertation maps and navigates contemporary literature by indigenous Chamorro authors from the Pacific island of Guam. Because Guam has experienced more than three centuries of colonization by three different imperial nations, Chamorro language, beliefs, customs, practices, identities, and aesthetics have been suppressed, changed, and sometimes completely replaced. As a result of these colonial changes, many anthropologists and historians have claimed that authentically indigenous Chamorro culture no longer exists. Similarly, literary scholars have argued that contemporary Chamorro literature is degraded and inauthentic because it is often composed in a written form as opposed to an oral form, in English as opposed to Chamorro, and in a foreign genre (such as a novel) as opposed to an indigenous genre (such as a chant). This discourse of inauthenticity, I suggest, is based on an understanding of Chamorro culture and literature as static essences that once existed in a "pure" and "authentic" state before colonialism, modernity, and globalization. Countering these arguments, I view Chamorro culture as a dynamic entity composed of core, enduring values, customs, and practices that are continually transformed and re-articulated within various historical contexts and political pressures.