Reef Shark Science – Key Questions and Future Directions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status and Demographic Analysis of the Dusky Shark, Carcharhinus Obscurus, in the Northwest Atlantic

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2004 Status and Demographic Analysis of the Dusky Shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, in the Northwest Atlantic Jason G. Romine College of William and Mary - Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Biostatistics Commons, Fresh Water Studies Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Romine, Jason G., "Status and Demographic Analysis of the Dusky Shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, in the Northwest Atlantic" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539617821. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25773/v5-zm7f-h314 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Status and demographic analysis of the Dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, in the Northwest Atlantic A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Marine Science The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Jason G. Romine 2004 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Master of Science Jason G. KOmine Approved, August 2004 NloW A. Musick, Ph.D. Committee Chairman/Advisor Kim N. Holland, Ph.D Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology University of Hawaii Kaneohe, Hawaii onn E. Olney, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........................................................................................................ v LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................................vi LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................................... -

First Records of the Sicklefin Lemon Shark, Negaprion Acutidens, at Palmyra Atoll, Central Pacific

Marine Biodiversity Records, page 1 of 3. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2014 doi:10.1017/S175526721400116X; Vol. 7; e114; 2014 Published online First records of the sicklefin lemon shark, Negaprion acutidens, at Palmyra Atoll, central Pacific: a recent colonization event? yannis p. papastamatiou1, chelsea l. wood2, darcy bradley3, douglas j. mccauley4, amanda l. pollock5 and jennifer e. caselle6 1School of Biology, Scottish Oceans Institute, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, KY16 8LB, UK, 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan, Michigan 48109, USA, 3Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA, 4Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology, University of California Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA, 5US Fish and Wildlife Service, Hawaii, 96850, USA, 6Marine Science Institute, University of California Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA The range of the sicklefin lemon shark (Negaprion acutidens) is expanded to include Palmyra Atoll, in the Northern Line Islands, central Pacific. Despite the fact that researchers have been studying reef and lagoon flat habitats of the Atoll since 2003, lemon sharks were first observed in 2010, suggesting a recent colonization event. To date, only juveniles and sub-adult sharks have been observed. Keywords: competition, Line Islands, range expansion, sharks Submitted 15 August 2014; accepted 23 September 2014 INTRODUCTION MATERIALS AND METHODS Shark reproduction does not involve a larval stage, so dispersal Study site can occur only through swimming of neonate, juvenile, or adult individuals from one location to another (Heupel Observations were made at Palmyra Atoll (5854′N 162805′W), et al., 2010; Lope˙z-Garro et al., 2012; Whitney et al., 2012). -

Phylogeny of the Damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and Patterns of Asymmetrical Diversification in Body Size and Feeding Ecology

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.07.430149; this version posted February 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Phylogeny of the damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and patterns of asymmetrical diversification in body size and feeding ecology Charlene L. McCord a, W. James Cooper b, Chloe M. Nash c, d & Mark W. Westneat c, d a California State University Dominguez Hills, College of Natural and Behavioral Sciences, 1000 E. Victoria Street, Carson, CA 90747 b Western Washington University, Department of Biology and Program in Marine and Coastal Science, 516 High Street, Bellingham, WA 98225 c University of Chicago, Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, and Committee on Evolutionary Biology, 1027 E. 57th St, Chicago IL, 60637, USA d Field Museum of Natural History, Division of Fishes, 1400 S. Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, IL 60605 Corresponding author: Mark W. Westneat [email protected] Journal: PLoS One Keywords: Pomacentridae, phylogenetics, body size, diversification, evolution, ecotype Abstract The damselfishes (family Pomacentridae) inhabit near-shore communities in tropical and temperature oceans as one of the major lineages with ecological and economic importance for coral reef fish assemblages. Our understanding of their evolutionary ecology, morphology and function has often been advanced by increasingly detailed and accurate molecular phylogenies. Here we present the next stage of multi-locus, molecular phylogenetics for the group based on analysis of 12 nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences from 330 of the 422 damselfish species. -

Stegastes Partitus (Bicolour Damselfish)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Stegastes partitus (Bicolour Damselfish) Family: Pomacentridae (Damselfish and Clownfish) Order: Perciformes (Perch and Allied Fish) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fish) Fig. 1. Bicolour damselfish, Stegastes partitus. [http://reefguide.org/carib/bicolordamsel.html, downloaded 14 March 2015] TRAITS. Stegastes partitus is one of the five most commonly found fishes amongst the coral reefs within Trinidad and Tobago. Length: total length in males and females is 10cm (Rainer, n.d.). Contains a total of 12 dorsal spines and 14-17 dorsal soft rays in addition to a total of 2 anal spines and 13-15 anal soft rays. A blunt snout is present on the head with a petite mouth and outsized eyes. Colour: Damsels show even distribution of black and white coloration with a yellow section separating both between the last dorsal spine and the anal fin (Fig. 1), however during mating, males under differentiation in their coloration (Schultz, 2008). There are colour variations depending on the geographic region and juveniles differ from the adults. UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology DISTRIBUTION. Distribution is spread throughout the western Atlantic (Fig. 2), spanning from Florida to the Bahamas and the Caribbean with possible extension to Brazil (Rainer, n.d.). They are also found along the coast of Mexico. HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. Found at a depth of approximately 30m, damsels are found in habitats bordering coral reefs, that is areas of dead coral, boulders and man-made structures where algae is most likely to grow. -

Social Learning in Juvenile Lemon Sharks, Negaprion Brevirostris

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 1-2013 Social Learning in Juvenile Lemon Sharks, Negaprion brevirostris Tristan L. Guttridge University of Leeds Sander van Dijk University of Groningen Eize Stamhuis University of Groningen Jens Krause Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries Samuel Gruber Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_asie Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Comparative Psychology Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Guttridge, T. L., van Dijk, S., Stamhuis, E. J., Krause, J., Gruber, S. H., & Brown, C. (2013). Social learning in juvenile lemon sharks, Negaprion brevirostris. Animal cognition, 16(1), 55-64. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Tristan L. Guttridge, Sander van Dijk, Eize Stamhuis, Jens Krause, Samuel Gruber, and Culum Brown This article is available at WBI Studies Repository: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_asie/86 Social learning in juvenile lemon sharks, Negaprion brevirostris Tristan L. Guttridge1,5, Sander van Dijk2, Eize J. Stamhuis2, Jens Krause3, Samuel H. Gruber4, Culum Brown5 1 University of Leeds 2 University of Groningen 3 Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries 4 Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science 5 Macquarie University KEYWORDS local and stimulus enhancement, group living, social facilitation, social information use, Elasmobranchs ABSTRACT Social learning is taxonomically widespread and can provide distinct behavioural advantages, such as in finding food or avoiding predators more efficiently. -

Influence of Predation Risk on the Sheltering Behaviour of the Coral-Dwelling Damselfish, Pomacentrus Moluccensis

Environ Biol Fish (2018) 101:639–651 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-018-0725-3 Influence of predation risk on the sheltering behaviour of the coral-dwelling damselfish, Pomacentrus moluccensis Robin P. M. Gauff & Sonia Bejarano & Hawis H. Madduppa & Beginer Subhan & Elyne M. A. Dugény & Yuda A. Perdana & Sebastian C. A. Ferse Received: 27 August 2017 /Accepted: 11 January 2018 /Published online: 24 January 2018 # The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract Predation is a key ecosystem function, espe- from their host colony was measured here as a proxy for cially in high diversity systems such as coral reefs. Not sheltering strength and was expected to be shortest under only is predation one of the strongest top-down controls of highest predation risk. Predation risk, defined as a func- prey population density, but it also is a strong driver of tion of predator abundance and activity, turbidity and prey behaviour and function through non-lethal effects. habitat complexity, was quantified at four reef slope sites We ask whether predation risk influences sheltering be- in Kepulauan Seribu, Indonesia. Damselfish sheltering haviour of damselfish living in mutualism with branching strength was measured using stationary unmanned video corals. Host corals gain multiple advantages from the cameras. Small damselfish (< 2 cm) increased their shel- mutualistic relationship which are determined by the tering strength under high turbidity. Predator feeding ac- strength of damselfish sheltering. Distance travelled by tivity, but not abundance, influenced damselfish sheltering the Lemon Damselfish Pomacentrus moluccensis away strength. Contrary to our expectations, sheltering behav- iour of adult damselfish decreased under high predator activity. -

Field Guide to Requiem Sharks (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Carcharhinidae) of the Western North Atlantic

Field guide to requiem sharks (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Carcharhinidae) of the Western North Atlantic Item Type monograph Authors Grace, Mark Publisher NOAA/National Marine Fisheries Service Download date 24/09/2021 04:22:14 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/20307 NOAA Technical Report NMFS 153 U.S. Department A Scientific Paper of the FISHERY BULLETIN of Commerce August 2001 (revised November 2001) Field Guide to Requiem Sharks (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Carcharhinidae) of the Western North Atlantic Mark Grace NOAA Technical Report NMFS 153 A Scientific Paper of the Fishery Bulletin Field Guide to Requiem Sharks (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Carcharhinidae) of the Western North Atlantic Mark Grace August 2001 (revised November 2001) U.S. Department of Commerce Seattle, Washington Suggested reference Grace, Mark A. 2001. Field guide to requiem sharks (Elasmobranchiomorphi: Carcharhinidae) of the Western North Atlantic. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Rep. NMFS 153, 32 p. Online dissemination This report is posted online in PDF format at http://spo.nwr.noaa.gov (click on Technical Reports link). Note on revision This report was revised and reprinted in November 2001 to correct several errors. Previous copies of the report, dated August 2001, should be destroyed as this revision replaces the earlier version. Purchasing additional copies Additional copies of this report are available for purchase in paper copy or microfiche from the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161; 1-800-553-NTIS; http://www.ntis.gov. Copyright law Although the contents of the Technical Reports have not been copyrighted and may be reprinted entirely, reference to source is appreciated. -

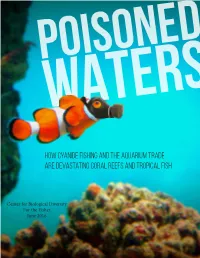

Poisoned Waters

POISONED WATERS How Cyanide Fishing and the Aquarium Trade Are Devastating Coral Reefs and Tropical Fish Center for Biological Diversity For the Fishes June 2016 Royal blue tang fish / H. Krisp Executive Summary mollusks, and other invertebrates are killed in the vicinity of the cyanide that’s squirted on the reefs to he release of Disney/Pixar’s Finding Dory stun fish so they can be captured for the pet trade. An is likely to fuel a rapid increase in sales of estimated square meter of corals dies for each fish Ttropical reef fish, including royal blue tangs, captured using cyanide.” the stars of this widely promoted new film. It is also Reef poisoning and destruction are expected to likely to drive a destructive increase in the illegal use become more severe and widespread following of cyanide to catch aquarium fish. Finding Dory. Previous movies such as Finding Nemo The problem is already widespread: A new Center and 101 Dalmatians triggered a demonstrable increase for Biological Diversity analysis finds that, on in consumer purchases of animals featured in those average, 6 million tropical marine fish imported films (orange clownfish and Dalmatians respectively). into the United States each year have been exposed In this report we detail the status of cyanide fishing to cyanide poisoning in places like the Philippines for the saltwater aquarium industry and its existing and Indonesia. An additional 14 million fish likely impacts on fish, coral and other reef inhabitants. We died after being poisoned in order to bring those also provide a series of recommendations, including 6 million fish to market, and even the survivors reiterating a call to the National Marine Fisheries are likely to die early because of their exposure to Service, U.S. -

Growth and Life History Variability of the Grey Reef Shark (Carcharhinus Amblyrhynchos) Across Its Range Darcy Bradley University of California, Santa Barbara

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Center for Coastal Oceans Research Faculty Institute of Water and Enviornment Publications 2-16-2017 Growth and life history variability of the grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) across its range Darcy Bradley University of California, Santa Barbara Eric Conklin The Nature Conservancy Yannis P. Papastamatiou Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, [email protected] Douglas J. McCauley University of California, Santa Barbara Kydd Pollock The Nature Conservancy See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/merc_fac Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bradley D, Conklin E, Papastamatiou YP, McCauley DJ, Pollock K, Kendall BE, et al. (2017) Growth and life history variability of the grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) across its range. PLoS ONE 12(2): e0172370. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0172370 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Water and Enviornment at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Coastal Oceans Research Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Darcy Bradley, Eric Conklin, Yannis P. Papastamatiou, Douglas J. McCauley, Kydd Pollock, Bruce E. Kendell, Steven D. Gaines, and Jennifer E. Caselle This article is available at FIU Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/merc_fac/2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Growth and life history variability of the grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) across its range Darcy Bradley1*, Eric Conklin2, Yannis P. Papastamatiou3, Douglas J. McCauley4,5, Kydd Pollock2, Bruce E. -

White-Tip Reef Shark (Triaenodon Obesus) Michelle S

White-tip Reef Shark (Triaenodon obesus) Michelle S. Tishler Common Name There are several common names for the Triaenodon obesus, which usually describes the “white tips” on their dorsal and caudal fins. Common names include: White-tip Reef Shark, Blunthead Shark, Light-Tip Shark and Reef Whitetip. Names in Spanish Cazón, Cazón Coralero Trompacorta and Tintorera Punta Aleta Blanca. Taxonomy Domain Eukarya Kingdom Anamalia Phylum Chordata Class Chondrichthyes Order Carcharhiniformes Family Carcharhinidae Genus Triaenodon Species obesus Nearest relatives Sharks are cartilaginous fishes in the class Chondrichthyes with skates, rays and other sharks. Within the family Carcharhinidae (requiem sharks), the White-tip Reef Shark is related to the Galapagos Shark, Bull Shark, Oceanic Whitetip, Tiger Shark and Blue Sharks. The White-tip Reef Shark does not share their genus name with any other organism. Island They are found amongst the reefs surrounding most or all of the Galapagos Islands. Geographic range White-tip Sharks range geographically from Costa Rica, Ecuador, Galapagos, Cocos, South Africa, Red Sea, Pakistan and etc. to primarily residing in the Indo-West Pacific region. (Red region indicates distribution of White-tip Reef Shark) Habitat Description As described in their name, White-tip Reef Sharks live amongst coral reefs with a home range of a couple square miles. They are also found in sandy patches and deeper waters. During the day these sharks tend to rest on the seabed or within caves and crevices. Physical description White-tip Reef sharks are named after the white tip on the dorsal (first and sometimes second) fins, and caudal fin lobes. -

Sharks and Rays

SHARKS AND RAYS Photo by: © Jim Abernethy Transboundary Species - Content ... 31 32 33 34 35 ... Overview As stated in the previous section, the establishment of the Yarari fishing for sharks in the Netherlands and places new pressure on Marine Mammal and Shark Sanctuary was an important step fishermen to implement new techniques and updated fishing gear in protecting the shark and ray species of the Dutch Caribbean. to avoid accidentally catching sharks and rays as bycatch. Overall, there is a significant lack of information concerning these vital species within Dutch Caribbean waters. Fortunately, this There are several different international treaties and legisla- trend is changing and in the last few years there has been a push tion which offer protection to these species. This includes the to increase research, filling in the historic knowledge gap. Sharks Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and rays are difficult species to protect as they tend to have long the Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) protocol and reproduction cycles, varying between 3 and 30 years, small litters, the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). Scientists are just which means they do not recover quickly when overfished and can beginning to uncover the complexities of managing conservation travel over great distances which makes them difficult to track. efforts for these species, as they often have long migration routes which put them in danger if international waters are not managed Early in 2019, the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality and protected equally. (LNV) published a strategy document to manage and protect sharks and rays within waters the Netherlands influences (this There are more than thirty different species of sharks and includes the North Sea, Dutch Caribbean and other international rays which are known to inhabit the waters around the Dutch waters). -

SHARK Shooter Experience Mike Ball Dive Expeditions

SHARK Shooter Experience Mike Ball Dive Expeditions Presentation compiled by: ABOUT – Mike Ball Dive Expeditions Co-Founding member of Global Shark Diving … ABOUT Mike Ball Dive Expeditions • 1969, Mike Ball commenced business. • 1987, commenced shark diving at Hungry Jacks in the Coral Sea. • 2002, Mike Ball, 1st liveaboard operator inducted into the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame. • 2014, Co-Founding Member of Global Shark Diving. SHARK Diving Awareness GLOBAL SHARK DIVING Our global alliance of shark diving operators ensures: • Your safety is our primary concern. • We are dedicated to Shark Conservation. • We support & facilitate Shark Research. SHARK Shooter Experience ABOUTS - Sharks • Osprey sharks are one of the worlds thriving shark populations due to the interest of dive vessels. • Grey reef shark have 26-28 rows of teeth, white tip have 80-100 total rows. • A single lost tooth is replaced naturally in one day. • Sharks filter oxygen through gills (some can do it when stationary). • They can detect vibrations & electrical Question: How many fins do sharks have? signals i.e. camera strobes. 5: Dorsal & Caudal Pectoral, Pelvic & Anal. SHARK Diving Awareness SHARK SPECIES - Commonly Seen White Tip Reef Shark Grey Reef Shark Silver Tip Shark • Adults up to 1.6m- 5f/4inches. • Adults up to 1.8m- 6f/4inches. • Resemble a larger, bulkier • Slim, tube shape. • V shape from side or above. grey reef shark. • White tip on dorsal & upper • May have a white tip on dorsal. • White tip & border on all fins. caudal fin. SHARK Shooter Experience SHARK SPECIES - Occasionally Seen Wobbegong Shark Thresher Shark (Infrequent Sightings) Scalloped Epaulette Shark Hammer Head Shark (April – Sept) Leopard Shark Tiger Shark (Very Rarely Sighted) SHARK Diving Awareness 3 SHARK DIVES – From Spoilsport SHARK ATTRACTION SHARK FEED PRIVATE SHARK SHOOT • Approx.