Influence of Predation Risk on the Sheltering Behaviour of the Coral-Dwelling Damselfish, Pomacentrus Moluccensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeny of the Damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and Patterns of Asymmetrical Diversification in Body Size and Feeding Ecology

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.07.430149; this version posted February 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Phylogeny of the damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and patterns of asymmetrical diversification in body size and feeding ecology Charlene L. McCord a, W. James Cooper b, Chloe M. Nash c, d & Mark W. Westneat c, d a California State University Dominguez Hills, College of Natural and Behavioral Sciences, 1000 E. Victoria Street, Carson, CA 90747 b Western Washington University, Department of Biology and Program in Marine and Coastal Science, 516 High Street, Bellingham, WA 98225 c University of Chicago, Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, and Committee on Evolutionary Biology, 1027 E. 57th St, Chicago IL, 60637, USA d Field Museum of Natural History, Division of Fishes, 1400 S. Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, IL 60605 Corresponding author: Mark W. Westneat [email protected] Journal: PLoS One Keywords: Pomacentridae, phylogenetics, body size, diversification, evolution, ecotype Abstract The damselfishes (family Pomacentridae) inhabit near-shore communities in tropical and temperature oceans as one of the major lineages with ecological and economic importance for coral reef fish assemblages. Our understanding of their evolutionary ecology, morphology and function has often been advanced by increasingly detailed and accurate molecular phylogenies. Here we present the next stage of multi-locus, molecular phylogenetics for the group based on analysis of 12 nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences from 330 of the 422 damselfish species. -

Stegastes Partitus (Bicolour Damselfish)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Stegastes partitus (Bicolour Damselfish) Family: Pomacentridae (Damselfish and Clownfish) Order: Perciformes (Perch and Allied Fish) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fish) Fig. 1. Bicolour damselfish, Stegastes partitus. [http://reefguide.org/carib/bicolordamsel.html, downloaded 14 March 2015] TRAITS. Stegastes partitus is one of the five most commonly found fishes amongst the coral reefs within Trinidad and Tobago. Length: total length in males and females is 10cm (Rainer, n.d.). Contains a total of 12 dorsal spines and 14-17 dorsal soft rays in addition to a total of 2 anal spines and 13-15 anal soft rays. A blunt snout is present on the head with a petite mouth and outsized eyes. Colour: Damsels show even distribution of black and white coloration with a yellow section separating both between the last dorsal spine and the anal fin (Fig. 1), however during mating, males under differentiation in their coloration (Schultz, 2008). There are colour variations depending on the geographic region and juveniles differ from the adults. UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology DISTRIBUTION. Distribution is spread throughout the western Atlantic (Fig. 2), spanning from Florida to the Bahamas and the Caribbean with possible extension to Brazil (Rainer, n.d.). They are also found along the coast of Mexico. HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. Found at a depth of approximately 30m, damsels are found in habitats bordering coral reefs, that is areas of dead coral, boulders and man-made structures where algae is most likely to grow. -

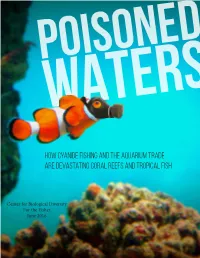

Poisoned Waters

POISONED WATERS How Cyanide Fishing and the Aquarium Trade Are Devastating Coral Reefs and Tropical Fish Center for Biological Diversity For the Fishes June 2016 Royal blue tang fish / H. Krisp Executive Summary mollusks, and other invertebrates are killed in the vicinity of the cyanide that’s squirted on the reefs to he release of Disney/Pixar’s Finding Dory stun fish so they can be captured for the pet trade. An is likely to fuel a rapid increase in sales of estimated square meter of corals dies for each fish Ttropical reef fish, including royal blue tangs, captured using cyanide.” the stars of this widely promoted new film. It is also Reef poisoning and destruction are expected to likely to drive a destructive increase in the illegal use become more severe and widespread following of cyanide to catch aquarium fish. Finding Dory. Previous movies such as Finding Nemo The problem is already widespread: A new Center and 101 Dalmatians triggered a demonstrable increase for Biological Diversity analysis finds that, on in consumer purchases of animals featured in those average, 6 million tropical marine fish imported films (orange clownfish and Dalmatians respectively). into the United States each year have been exposed In this report we detail the status of cyanide fishing to cyanide poisoning in places like the Philippines for the saltwater aquarium industry and its existing and Indonesia. An additional 14 million fish likely impacts on fish, coral and other reef inhabitants. We died after being poisoned in order to bring those also provide a series of recommendations, including 6 million fish to market, and even the survivors reiterating a call to the National Marine Fisheries are likely to die early because of their exposure to Service, U.S. -

(Zebrafish and Ambon Damselfish) Emmanuel Ma

Visual learning and its underlying neural substrate in two species of teleost fish (Zebrafish and Ambon damselfish) Emmanuel Marquez-Legorreta Bachelor in Psychology Master in Neuroscience A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 The Faculty of Medicine Abstract The visual sense is one of the main sources of information for many animals. In particular, many species of fish rely on vision for survival. Whether a fish needs to distinguish between possible predators, sources of food, a possible mate or competitors for their territory, learning to discriminate between visual stimuli is fundamental part of their life. Recently, studies have shown that multiple species of fish are able to solve visual discrimination tasks that were thought to be too complex for these organisms (Brown et al., 2011). Furthermore, neuroanatomical studies have also found that although the layout of the central nervous system of teleost fish is different, multiple structures seem to have homologues in mammalian brains (Mueller et al., 2011). Together, these findings have reinforced the role of fish as a model system to study the neuronal substrates of simple and complex behaviours (Gerlai, 2014). A particular case is the one of zebrafish, whose development as a model for neuroscience has been exceptionally rapid (Stewart et al., 2010; Blaser and Vira, 2014; Kalueff et al., 2014; Stewart et al., 2014a; d'Amora and Giordani, 2018). In the last decade, the combination of genetic and optical technology has allowed the neuronal activity imaging of the whole brain of zebrafish larvae (Ahrens et al., 2013a; Wolf et al., 2015; Vanwalleghem et al., 2018). -

The Role of Threespot Damselfish (Stegastes Planifrons)

THE ROLE OF THREESPOT DAMSELFISH (STEGASTES PLANIFRONS) AS A KEYSTONE SPECIES IN A BAHAMIAN PATCH REEF A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Science Brooke A. Axline-Minotti August 2003 This thesis entitled THE ROLE OF THREESPOT DAMSELFISH (STEGASTES PLANIFRONS) AS A KEYSTONE SPECIES IN A BAHAMIAN PATCH REEF BY BROOKE A. AXLINE-MINOTTI has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences by Molly R. Morris Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Axline-Minotti, Brooke A. M.S. August 2003. Environmental Studies The Role of Threespot Damselfish (Stegastes planifrons) as a Keystone Species in a Bahamian Patch Reef. (76 pp.) Director of Thesis: Molly R. Morris Abstract The purpose of this research is to identify the role of the threespot damselfish (Stegastes planifrons) as a keystone species. Measurements from four functional groups (algae, coral, fish, and a combined group of slow and sessile organisms) were made in various territories ranging from zero to three damselfish. Within territories containing damselfish, attack rates from the damselfish were also counted. Measures of both aggressive behavior and density of threespot damselfish were correlated with components of biodiversity in three of the four functional groups, suggesting that damselfish play an important role as a keystone species in this community. While damselfish density and measures of aggression were correlated, in some cases only density was correlated with a functional group, suggesting that damselfish influence their community through mechanisms other than behavior. -

Pomacentridae): Structural and Expression Variation in Opsin Genes

Molecular Ecology (2017) 26, 1323–1342 doi: 10.1111/mec.13968 Why UV vision and red vision are important for damselfish (Pomacentridae): structural and expression variation in opsin genes SARA M. STIEB,*† FABIO CORTESI,*† LORENZ SUEESS,* KAREN L. CARLETON,‡ WALTER SALZBURGER† and N. J. MARSHALL* *Sensory Neurobiology Group, Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia, †Zoological Institute, University of Basel, Basel 4051, Switzerland, ‡Department of Biology, The University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA Abstract Coral reefs belong to the most diverse ecosystems on our planet. The diversity in col- oration and lifestyles of coral reef fishes makes them a particularly promising system to study the role of visual communication and adaptation. Here, we investigated the evolution of visual pigment genes (opsins) in damselfish (Pomacentridae) and exam- ined whether structural and expression variation of opsins can be linked to ecology. Using DNA sequence data of a phylogenetically representative set of 31 damselfish species, we show that all but one visual opsin are evolving under positive selection. In addition, selection on opsin tuning sites, including cases of divergent, parallel, conver- gent and reversed evolution, has been strong throughout the radiation of damselfish, emphasizing the importance of visual tuning for this group. The highest functional variation in opsin protein sequences was observed in the short- followed by the long- wavelength end of the visual spectrum. Comparative gene expression analyses of a subset of the same species revealed that with SWS1, RH2B and RH2A always being expressed, damselfish use an overall short-wavelength shifted expression profile. Inter- estingly, not only did all species express SWS1 – a UV-sensitive opsin – and possess UV-transmitting lenses, most species also feature UV-reflective body parts. -

Temporal Patterns of Spawning and Larval Hatching in the Temperate Reef

1 Temporal patterns of spawning and hatching in a spawning aggregation of the 2 temperate reef fish Chromis hypsilepis (Pomacentridae)1 3 4 William Gladstone 5 6 School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle, PO Box 127, 7 Ourimbah NSW 2258, Australia 8 9 E-mail: [email protected] 10 Tel.: + 61-2-43484123 11 Fax: + 61-2-43484145 12 1 This is the final corrected version of the ms that was accepted and published in Marine Biology 151:1143-1152 (2007). 1 13 Abstract Descriptions of temporal patterns in the reproduction of damselfishes 14 (family Pomacentridae) and adaptive hypotheses for these patterns are derived mostly 15 from studies of coral reef species. It is unclear whether the types of temporal patterns 16 and the explanatory power of the adaptive hypotheses are applicable to damselfishes 17 of temperate rocky reefs. This study tested hypotheses about the existence of lunar 18 spawning cycles, the diel timing of hatching, and the synchronization of temporal 19 patterns in hatching and tides in the schooling planktivorous damselfish Chromis 20 hypsilepis on a rocky reef in New South Wales, Australia. Reproductive behaviour 21 was observed daily for 223 d between August 2004 and March 2005. C. hypsilepis 22 formed large spawning aggregations of 3,575–33,075 individuals. Spawning occurred 23 at a uniform rate throughout the day on a semi-lunar cycle. The greatest number of 24 spawnings occurred 1 d after the new moon and 1 d before the full moon. The cost to 25 males from brood care was an 85% reduction in their feeding rate. -

Patterns of Evolution in Gobies (Teleostei: Gobiidae): a Multi-Scale Phylogenetic Investigation

PATTERNS OF EVOLUTION IN GOBIES (TELEOSTEI: GOBIIDAE): A MULTI-SCALE PHYLOGENETIC INVESTIGATION A Dissertation by LUKE MICHAEL TORNABENE BS, Hofstra University, 2007 MS, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MARINE BIOLOGY Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Corpus Christi, Texas December 2014 © Luke Michael Tornabene All Rights Reserved December 2014 PATTERNS OF EVOLUTION IN GOBIES (TELEOSTEI: GOBIIDAE): A MULTI-SCALE PHYLOGENETIC INVESTIGATION A Dissertation by LUKE MICHAEL TORNABENE This dissertation meets the standards for scope and quality of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi and is hereby approved. Frank L. Pezold, PhD Chris Bird, PhD Chair Committee Member Kevin W. Conway, PhD James D. Hogan, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Lea-Der Chen, PhD Graduate Faculty Representative December 2014 ABSTRACT The family of fishes commonly known as gobies (Teleostei: Gobiidae) is one of the most diverse lineages of vertebrates in the world. With more than 1700 species of gobies spread among more than 200 genera, gobies are the most species-rich family of marine fishes. Gobies can be found in nearly every aquatic habitat on earth, and are often the most diverse and numerically abundant fishes in tropical and subtropical habitats, especially coral reefs. Their remarkable taxonomic, morphological and ecological diversity make them an ideal model group for studying the processes driving taxonomic and phenotypic diversification in aquatic vertebrates. Unfortunately the phylogenetic relationships of many groups of gobies are poorly resolved, obscuring our understanding of the evolution of their ecological diversity. This dissertation is a multi-scale phylogenetic study that aims to clarify phylogenetic relationships across the Gobiidae and demonstrate the utility of this family for studies of macroevolution and speciation at multiple evolutionary timescales. -

An Indo-Pacific Damselfish Well Established in the Southern Gulf of Mexico: Prospects for a Wider, Adverse Invasion

An Indo-Pacific damselfish well established in the southern Gulf of Mexico: prospects for a wider, adverse invasion D. ROSS ROBERTSON Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panama E-mail: [email protected] NUNO SIMOES Unidad Multidisciplinaria en Docencia e Investigación de Sisal, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, Yucatan, México E-mail: [email protected] CARLA GUTIÉRREZ RODRÍGUEZ Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Xalapa. Veracruz, México E-mail: [email protected] VICTOR J. PIÑEROS Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Xalapa. Veracruz, México E-mail: [email protected] HORACIO PEREZ-ESPAÑA Instituto de Ciencias Marinas y Pesquerías, Universidad Veracruzana, Hidalgo 617, Col. Río Jamapa, C.P. 94290, Boca del Río, Veracruz, México E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Indo-west Pacific damselfish Neopomacentrus cyanomos was first recorded in the West Atlantic in 2013, when it was found to be common on reefs near Coatzacoalcos, in the extreme southwest corner Gulf of Mexico. During 2014–2015, this species also was found on reefs farther afield in that area, but not in the northwest Gulf, nor the north-eastern tip of the Yucatan peninsula. These data, and information from public databases on invasive reef fishes, indicate that N. cyanomos currently is widely distributed in, but restricted to, the southwest Gulf of Mexico. Mitochondrial DNA barcodes of N. cyanomos from that area match to those for this species from its natural range, but do not indicate the ultimate origin of the Gulf of Mexico fish. Possible modes of introduction to the Gulf of Mexico and the potential for its further spread with negative effects on the native reef-fish fauna are discussed, and directions for future research suggested. -

Larval Transport and Dispersal in the Coastal Ocean and Consequences for Population Connectivity

MARI N E P O P ULATIO N C O nn E C TI V ITY Larval Transport and Dispersal in the Coastal Ocean and Consequences for Population Connectivity BY JESÚS PI N E D A , J O N ATHA N A . H A R E , A nd S U Sp O N AUGLE MA N Y M ARI N E S P E C IES have small, pelagic early life stages. For those spe- cies, knowledge of population connectivity requires understanding the origin and trajectories of dispersing eggs and larvae among subpopulations. Researchers have used various terms to describe the movement of eggs and larvae in the marine envi- ronment, including larval dispersal, dispersion, drift, export, retention, and larval transport. Though these terms are intuitive and relevant for understanding the spatial dynamics of populations, some may be nonoperational (i.e., not measur- able), and the variety of descriptors and approaches used makes studies difficult to compare. Furthermore, the assumptions that underlie some of these concepts are rarely identified and tested. Here, we describe two phenomenologi- cally relevant concepts, larval transport and larval dispersal. These concepts have corresponding operational definitions, are relevant to understanding population connectivity, and have a long history in the literature, although they are sometimes confused and used interchangeably. After defin- ing and discussing larval transport and dispersal, we consider the relative importance of planktonic processes to the overall understanding and measurement of popula- tion connectivity. The ideas considered in this contribution are applicable to most benthic and pelagic species that undergo transforma- tions among life stages. -

Literature Review the Benefits of Wild Caught Ornamental Aquatic Organisms

LITERATURE REVIEW THE BENEFITS OF WILD CAUGHT ORNAMENTAL AQUATIC ORGANISMS 1 Submitted to the ORNAMENTAL AQUATIC TRADE ASSOCIATION October 2015 by Ian Watson and Dr David Roberts Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology [email protected] School of Anthropology and Conservation http://www.kent.ac.uk/sac/index.html University of Kent Canterbury Kent CT2 7NR United Kingdom Disclaimer: the views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of DICE, UoK or OATA. 2 Table of Contents Acronyms Used In This Report ................................................................................................................ 8 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 10 Background to the Project .................................................................................................................... 13 Approach and Methodology ................................................................................................................. 13 Approach ........................................................................................................................................... 13 Literature Review Annex A ............................................................................................................ 13 Industry statistics Annex B .................................................................................................................... 15 Legislation -

Protogyny in a Tropical Damselfish: Females Queue for Future Benefit

Protogyny in a tropical damselfish: females queue for future benefit Mark I. McCormick ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, and Department of Marine Biology and Aquaculture, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland, Australia ABSTRACT Membership of the group is a balance between the benefits associated with group living and the cost of socially constrained growth and breeding opportunities, but the costs and benefits are seldom examined. The goal of the present study was to explore the trade-offs associated with group living for a sex-changing, potentially protogynous coral reef fish, the Ambon damselfish, Pomacentrus amboinensis. Extensive sampling showed that the species exhibits resource defence polygyny, where dominant males guard a nest site that is visited by females. P. amboinensis have a longevity of about 6.5 years on the northern Great Barrier Reef. While the species can change sex consistent with being a protogynous hermaphrodite, it is unclear the extent to which the species uses this capability. Social groups are comprised of one reproductive male, 1–7 females and a number of juveniles. Females live in a linear dominance hierarchy, with the male being more aggressive to the beta-female than the alpha-female, who exhibits lower levels of ovarian cortisol. Surveys and a tagging study indicated that groups were stable for at least three months. A passive integrated transponder tag study showed that males spawn with females from their own group, but also females from neighbouring groups. In situ behavioural observations found that alpha-females have priority of access to the nest site that the male guarded, and access to higher quality foraging areas.