How to Use Text As Data in the Field of Chinese Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

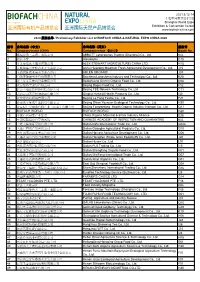

(CHN) 公司名称(英文) Company Name (ENG)

2021.5.12-14 上海世博展览馆3号馆 Shanghai World Expo Exhibition & Convention Center www.biofach-china.com 2020 展商名单 / Preliminary Exhibitor List of BIOFACH CHINA & NATURAL EXPO CHINA 2020 编号 公司名称(中文) 公司名称(英文) 展位号 No. Company name (CHN) Company name (ENG) Booth No. 1 雅培贸易(上海)有限公司 ABBOTT Laboratories Trading (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. N/A 2 阿拉小优 Alaxiaoyou C15 3 江苏安舜技术服务有限公司 ALEX STEWART (AGRICULTURE) CHINA LTD. H15 4 安徽华栋山中鲜农业开发有限公司 Anhui Huadong Mountain Fresh Agricultural Development Co., Ltd. J15 5 上海阿林农业果业专业合作社 ARLEN ORGANIC J01 6 白城市隆盛实业科技有限公司 Baicheng Longsheng Industry and Technology Co., Ltd. K20 7 北大荒亲民有机食品有限公司 Beidahuang Qinmin Organic Food Co., Ltd. E08 8 北京佰格士食品有限公司 Beijing Bages Food Co., Ltd. F12 9 北京中福必易网络科技有限公司 Beijing FBE Network Technology Co.,Ltd. C11 10 青海可可西里保健食品有限公司 Qinghai Kekexili Health Products Co., Ltd. I30 11 北京乐坊纺织品有限公司 Beijing Le Fang Textile Co., Ltd. F21 12 北京食安优选生态科技有限公司 Beijing Shian Youxuan Ecological Technology Co., Ltd. H30 13 北京同仁堂健康有机产业(海南)有限公司 Beijing Tongrentang Health Organic Industry (Hainan) Co., Ltd. Q11 14 BIOFACH WORLD BIOFACH WORLD G20 15 中国有机母婴产业联盟 China Organic Maternal & Infant Industry Alliance E25 16 中国检验检疫科学研究院 CHINESE ACADEMY OF INSPECTION AND QUARANTINE N/A 17 大连大福国际贸易有限公司 Dalian Dafu International Trade Co., Ltd. G02a 18 大连广和农产品有限公司 Dalian Guanghe Agricultural Products Co., Ltd. G10 19 大连盛禾谷农业发展有限公司 Dalian Harvest Agriculture Development Co., Ltd. G06 20 大连弘润全谷物食品有限公司 Dalian HongRen Whole Grain Foodstuffs Co., Ltd. J20 21 大连华恩有限公司 Dalian Huaen Co., Ltd. L01 22 大连浦力斯国际贸易有限公司 Dalian PLS Trading Co., Ltd. I15 23 大连盛方有机食品有限公司 Dalian Shengfang Organic Food Co., Ltd. H01 24 大连伟丰国际贸易有限公司 Dalian WeiFeng International Trade Co., Ltd. G07 25 大连鑫益农产品有限公司 Dalian Xinyi Organics Co., Ltd. -

Loan Agreement

CONFORMED COPY LOAN NUMBER 4829-CHA Public Disclosure Authorized Loan Agreement (Henan Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Project) Public Disclosure Authorized between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA and Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Dated September 1, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized LOAN NUMBER 4829-CHA LOAN AGREEMENT AGREEMENT, dated September 1, 2006, between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (the Borrower) and INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (the Bank). WHEREAS (A) the Borrower, having satisfied itself as to the feasibility and priority of the project described in Schedule 2 to this Agreement (the Project), has requested the Bank to assist in the financing of the Project; (B) the Project will be carried out by Henan (as defined in Section 1.02) with the Borrower’s assistance and, as part of such assistance, the Borrower will make the proceeds of the loan provided for in Article II of this Agreement (the Loan) available to Henan, as set forth in this Agreement; and WHEREAS the Bank has agreed, on the basis, inter alia, of the foregoing, to extend the Loan to the Borrower upon the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement and in the Project Agreement of even date herewith between the Bank and Henan (the Project Agreement); NOW THEREFORE the parties hereto hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I General Conditions; Definitions Section 1.01. The “General Conditions Applicable to Loan and Guarantee Agreements for Single Currency Loans” of the Bank, dated May 30, 1995 (as amended through May 1, 2004) with the following modifications (the General Conditions), constitute an integral part of this Agreement: (a) Section 5.08 of the General Conditions is amended to read as follows: “Section 5.08. -

1 Introduction Chinese Citizens Continue to Face Substantial Obstacles in Seeking Remedies to Government Actions That Violate Th

1 ACCESS TO JUSTICE Introduction Chinese citizens continue to face substantial obstacles in seeking remedies to government actions that violate their legal rights and constitutionally protected freedoms. International human rights standards require effective remedies for official violations of citi- zens’ rights. Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that ‘‘Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the funda- mental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.’’ 1 Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which China has signed but not yet ratified, requires that all parties to the ICCPR ensure that persons whose rights or free- doms are violated ‘‘have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.’’ 2 The Third Plenum and Judicial Reform The November 2013 Chinese Communist Party Central Com- mittee Third Plenum Decision on Certain Major Issues Regarding Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (Third Plenum Decision) con- tained several items relating to judicial system reform.3 In June 2014, the office of the Party’s Central Leading Small Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reform announced that six provinces and municipalities—Shanghai, Guangdong, Jilin, Hubei, Hainan, and Qinghai—would serve as pilot sites for certain judicial reforms, including divesting local governments of their control over local court funding and appointments and centralizing -

Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT. DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS AND SENIOR MANAGEMENT BOARD OF DIRECTORS App1A-41(1) The Board consists of eleven Directors, including five executive Directors, two non-executive 3rd Sch 6 Directors and four independent non-executive Directors. The Directors are elected for a term of three years and are subject to re-election, provided that the cumulative term of an independent non-executive Director shall not exceed six years pursuant to the relevant PRC laws and regulations. The following table sets forth certain information regarding the Directors. Time of Time of joining the joining the Thirteen Date of Position held Leading City Time of appointment as of the Latest Group Commercial joining the as a Practicable Name Age Office Banks Bank Director Date Responsibility Mr. DOU 54 December N/A December December Executive Responsible for the Rongxing 2013 2014 23, 2014 Director, overall management, (竇榮興) chairperson of strategic planning and the Board business development of the Bank Ms. HU 59 N/A January 2010 December December Executive In charge of the audit Xiangyun (Joined 2014 23, 2014 Director, vice department, regional (胡相雲) Xinyang chairperson of audit department I and Bank) the Board regional audit department II of the Bank Mr. WANG Jiong 49 N/A N/A December December Executive Responsible for the (王炯) 2014 23, 2014 Director, daily operation and president management and in charge of the strategic development department and the planning and financing department of the Bank Mr. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 5, 2017 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE 2017 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 5, 2017 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 26–811 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 16:24 Oct 04, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\26811 DIEDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TODD YOUNG, Indiana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota GARY PETERS, Michigan TED LIEU, California ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed ELYSE B. -

2019展商名单/Preliminary Exhibitor List Of

2019.5.16-18 Shanghai World Expo Exhibition & Convention Center www.biofach-china.com 2019展商名单 /Preliminary Exhibitor List of BIOFACH CHINA 2019 编号 公司名(中文) 公司名(英文) 展位号 No Company Name (Chi) Company Name (Eng) Booth No. 1 0+蛋糕 0+cake H08 2 上海市金山区农业农村委员会 Agricultural Committee of Jinshan District, Shanghai Municipality A55 3 阿军轻蔬食 Ajun Light Vegetable Food F01 4 阿拉尔新农乳业有限责任公司 Ala'er Xinnong Dairy Co., Ltd. A65 5 红醇坊企业有限公司 Alarcon Enterprise Limited C66 6 阿勒泰益康有机面业有限公司 Aletai Yikang Organic Noodle Co., Ltd. A65 7 江苏安舜技术服务有限公司 Alex Stewart (Agriculture) China. Ltd. A55 8 ALTERFOOD ALTERFOOD A15 9 AMA TIME AMA TIME D22 10 Amazing Cacao Amazing Cacao F15 11 Arla Foods Arla Foods A25&B20 12 阿林农业科技有限公司 ARLEN ORGANIC A55 13 阿蒂米斯橄榄油 Artemis olive oil F01 14 雅士利乳业(马鞍山)销售有限公司 Ashley Dairy (Ma'an Mountain) Sales Co., Ltd. A20 15 阿丝道食品 Asidao Food F01 16 Avonmore Estate Biodynamic Wines Pty Ltd Avonmore Estate Biodynamic Wines Pty Ltd C31 17 白城市隆盛实业科技有限公司 Baiheng Longsheng Industry and Technology Co., Ltd. D36 18 爵霸(上海)贸易有限公司 Bebebalm E08i 19 零榆环保材料科技(常熟)有限公司 BEEZIRO E08j 20 北大荒亲民有机食品有限公司 BEIDAHUANG QINMIN ORGANIC FOOD CO., LTD. C50 21 北京清源保生物科技有限公司 Beijing Kingbo Biotech Co., Ltd. E31 22 北京春播科技有限公司 Beijing Chunbo Technology Co., Ltd. D68 23 北京五洲恒通认证有限公司 Beijing Continental Hengtong Certification Co., Ltd. C80 24 北京中合金诺认证中心有限公司 BEIJING CO-OPS INTEGRITY CERTIFICATION CENTRE B83 25 北京德睿伟业国际贸易有限公司 Beijing Dairy International Trade Co., Ltd. D52 26 北京爱科赛尔认证中心有限公司 Beijing Ecocert Certification Center Co., Ltd. C52 27 北京乐坊纺织品有限公司 Beijing Le Fang Textile Co., Ltd. D29 28 北京天彩纺织服装有限公司 Beijing Rainbow Textiles & Garments Co., Ltd. B65 29 北京双娃乳业有限公司 Beijing SUVOW Dairy Co., Ltd. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

简报 in February 2016 2016年2月 2016年2月 中国社会福利基金会免费午餐基金管理委员会主办

免费午餐基金 FREE LUNCH FOR CHILDREN BRIEFING简报 IN FEBRUARY 2016 2016年2月 2016年2月 中国社会福利基金会免费午餐基金管理委员会主办 www.mianfeiwucan.org 学校执行汇报 Reports of Registered Schools: 截止2016年2月底 累计开餐学校 517 所 现有开餐学校 437所 现项目受惠人数 143359人 现有用餐人数 104869人 分布于全国23个省市自治区 By the end of February 2016, Free Lunch has found its footprints in 517 schools (currently 437) across 23 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions with a total of 143,359 beneficiaries and 104,869 currently registered for free lunches. 学校执行详细情况 Details: 2月免费午餐新开餐学校3所, 其中湖南1所,新疆1所,河北1所。 Additional 3 schools are included in the Free Lunch campaign, including 1 in Hunan, 1 in Xinjiang and 1 in Hebei. 学校开餐名单(以拨款时间为准) List of Schools(Grant date prevails): 学校编号 学校名称 微博地址 School No. School Name Weibo Link 2016001 湖南省张家界市桑植县利福塔乡九天洞苗圃学校 http://weibo.com/u/5608665513 Miaopu School of Jiutiandong village, Lifuta Town, Sangzhi County,Zhangjiajie,Hunan Province 2016002 新疆维吾尔族自治区阿克苏地区拜城县赛里木镇英巴格村小学 http://weibo.com/u/5735367760 Primary School of Yingbage Village, Sailimu Town, Baicheng County, Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region 2016003 河北省张家口市赤城县大海陀乡中心小学 http://weibo.com/5784417643 Central Primary School of Dahaituo Town, Chicheng County, Zhangjiakou, Hebei Province 更多学校信息请查看免费午餐官网学校公示页面 For more information about the schools, please view the school page at our official website http://www.mianfeiwucan.org/school/schoolinfo/ 财务数据公示 Financial Data: 2016年2月善款收入: 701万余元,善款支出: 499万余元 善款支出 499万 善款收入 701万 累计总收入 18829万 Donations received: RMB 7.01 million+; Expenditure: RMB 4.99 million+ As of the end of February 2016, Free Lunch for Children has a gross income of RMB 188.29 million. 您可进入免费午餐官网查询捐赠 You can check your donation at our official website: http://www.mianfeiwucan.org/donate/donation/ 项目优秀学校评选表彰名单 Outstanding Schools Name List: 寒假期间,我们对免费午餐的项目执行学校进行了评选表彰活动,感谢学校以辛勤的工作为孩子们带来 温暖安全的午餐。 During the winter holiday, we selected outstanding schools which implemented Free Lunch For Children Program, in recognition of hard work of school staff in providing students warm and safe lunches. -

Announcement of Annual Results for the Year Ended December 31, 2019

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (Stock Code of H Shares: 1216) (Stock Code of Preference Shares: 4617) ANNOUNCEMENT OF ANNUAL RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2019 The board of directors (the “Board”) of Zhongyuan Bank Co., Ltd. (the “Bank”) is pleased to announce the audited consolidated annual results (the “Annual Results”) of the Bank and its subsidiaries for the year ended December 31, 2019 (the “Reporting Period”) which were prepared in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRSs”). The Board and the audit committee of the Board have reviewed and confirmed the Annual Results. This results announcement is published on the websites of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk) and the Bank (www.zybank.com.cn). The annual report for the year ended December 31, 2019 will be despatched to the shareholders of the Bank and will be available on the above websites in due course. On behalf of the Board Zhongyuan Bank Co., Ltd.* DOU Rongxing Chairman Zhengzhou, the People’s Republic of China March 27, 2020 As at the date of this announcement, the Board comprises Mr. DOU Rongxing, Mr. WANG Jiong, Mr. LI Yulin and Mr. WEI Jie as executive directors; Mr. LI Qiaocheng, Mr. LI Xipeng and Mr. -

Biofach China & Natural Expo China

INFORME IF DE FERIA 2021 Biofach China & Natural Expo China Shanghái 12 - 14 de mayo de 2021 Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España en Shanghái INFORME IF DE FERIA 8 de junio de 2021 Shanghái Este estudio ha sido realizado por Jacobo González y Cesar Merino Bajo la supervisión de la Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España en Shanghái http://china.oficinascomerciales.es Editado por ICEX España Exportación e Inversiones, E.P.E. NIPO: 114-21-013-8 IF BIOFACH CHINA & NATURAL EXPO CHINA 2021 Índice 1. Perfil de la Feria 4 1.1. Ficha técnica 4 2. Descripción y evolución de la Feria 5 3. Valoración 6 4. Anexos 7 4.1. Anexo 1 – Lista de expositores 7 4.2. Anexo 2 – Plan de conferencias 11 3 Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España en Shanghái IF BIOFACH CHINA & NATURAL EXPO CHINA 2021 1. Perfil de la Feria 1.1. Ficha técnica BIOFACH CHINA 2021 & NATURAL EXPO CHINA 2021 Fechas de celebración del evento: 12 – 14 de mayo 2021 Fechas de la próxima edición: 11 – 13 de mayo 2022 Frecuencia, periodicidad: Anual Lugar de celebración: Shanghai World Expo Exhibition & Convention center – Hall 3 (1099 Guozhan Rd, Pudong Xinqu, Shanghai Shi, China) Horario de la feria: 9.00 – 16.30 (el sábado hasta las 15.00 horas) Precio de la entrada: Gratuita para la oficina y para profesionales (presentando la tarjeta de visita) Sectores y productos representados: Productos agroalimentarios orgánicos. Agencias con servicios de certificación de producción orgánica. Productos internacionales importados. Productos orgánicos infantiles. -

Download Download

Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights, Vol. 3 No. 2 December 2019 pp. 317 – 343 doi: 10.19184/jseahr.v%vi%i.13465 © University of Jember & Indonesian Consortium for Human Rights Lecturers The Long March in the New Era: Filling Implementation Gaps between Chinese Municipal Law and the International Human Rights Law on Non- Discrimination Qinxuan Peng Wuhan University Institute of International Law Email: [email protected] Abstract China has entered a New Era with an aspiration to safeguard human rights through law. However, implementation gaps are found when comparing the current Chinese domestic laws on non-discrimination with the requirements set by international human rights treaties and international labour standards on eliminating discrimination in the labour market. This article illustrates how rural migrant workers are an underprivileged group in Chinese society, emphasizing the inferior treatment they experience due to their agricultural hukou residential status in urban areas. The study identifies several implementation gaps between the international standards and the Chinese domestic legal system on non-discrimination, serving as the very first step to eradicate de facto and de jure discrimination and to achieve Legal Protection of Human Rights in the New Era. Keywords: New Era, non-discrimination, implementation gaps, multiple discrimination, legal protection of human rights 1. INTRODUCTION In 2017, President Xi Jinping announced that China had entered a New Era,1 one marked by the inclusivity of legal protection of human rights (Renquan Fazhihua Baozhang). During many of his public speeches, President Xi Jinping mentioned that the Communist Party is resolved to promote “comprehensive development of human beings”, and it is necessary to “enhance legal protection of human rights and to secure people‟s right and freedom according to the law”. -

China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) 2016 Human Rights Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the paramount authority. CCP members hold almost all top government and security apparatus positions. Ultimate authority rests with the CCP Central Committee’s 25-member Political Bureau (Politburo) and its seven-member Standing Committee. Xi Jinping continued to hold the three most powerful positions as CCP general secretary, state president, and chairman of the Central Military Commission. Civilian authorities maintained control of the military and internal security forces. Repression and coercion of organizations and individuals involved in civil and political rights advocacy as well as in public interest and ethnic minority issues remained severe. As in previous years, citizens did not have the right to choose their government and elections were restricted to the lowest local levels of governance. Authorities prevented independent candidates from running in those elections, such as delegates to local people’s congresses. Citizens had limited forms of redress against official abuse. Other serious human rights abuses included arbitrary or unlawful deprivation of life, executions without due process, illegal detentions at unofficial holding facilities known as “black jails,” torture and coerced confessions of prisoners, and detention and harassment of journalists, lawyers, writers, bloggers, dissidents, petitioners, and others whose actions the authorities deemed unacceptable. There was also a lack of due process in judicial proceedings, political control of courts and judges, closed trials, the use of administrative detention, failure to protect refugees and asylum seekers, extrajudicial disappearances of citizens, restrictions on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), discrimination against women, minorities, and persons with disabilities.