An Advocacy Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bulletin INF INDIANA NURSES FOUNDATION

THE BULLETIN INF INDIANA NURSES FOUNDATION Brought to you by the Indiana Nurses Foundation (INF) and the Indiana State Nurses Association (ISNA) whose Volume 42, No. 2 dues paying members make it possible to advocate for nurses and nursing at the state and federal level. February 2016 Quarterly publication direct mailed to approximately 106,000 RNs licensed in Indiana. Save the Date: Upcoming Meeting of the Members Presenting Your New Indiana Nurses Foundation Mark Your You may have noticed that ISNA was Calendar looking for members to get involved in the Indiana Nurses Foundation (INF). Well, it is now a reality and INF is off and running. If you want to donate money to your favorite charity, please consider INF. It’s easy, just go to Page 3 www.IndianaNurses.org, and click on “Indiana Nurses Foundation” under the “About Us” menu. The donation form is also on this web page. It is INF’s plan to fund small research grants by 2017. Policy Primer It is all about enhancing the nursing body of INF knowledge. INDIANA NURSES FOUNDATION For a Foundation to be successful, it must have dynamic leadership. Here is the dynamic leadership of INF for 2015-2017: President, Mike Fights from West Lafayette, Vice President Louise Hart from Winchester, Angie Heckman from Kokomo, and Ella Harmeyer from South Bend. Also serving on the Board are Diana Sullivan from Greenwood, Jeni Embree from Campbellsburg, Donation Form on page 2. Sue Johnson from Fort Wayne, Janet Adler from Merrillville and Gingy Harshey-Meade from Page 4 Hamilton. As I said, the INF is off and running! Message from the President Independent Study The ABC’s of Effective Advocacy: Attention, Advocate for Your Patient & Your Profession Bipartisanship, & Collaboration The legislative advocacy season is upon forever advocating for us. -

Participate in the Legislative Process

ParticipateParticipate inin thethe LegislativeLegislative ProcessProcess CECIL COUNTY 1. Attend a Council Meeting - COUNCIL WORK SESSIONS COUNCIL Every Tuesday (except 5th Tuesdays at 9:00 a.m. A Guide for Citizens on the County Council and Legislative Process Council discussions and presentation Agenda available online LEGISLATIVE BRANCH — County Council of Cecil County Audio recording available online CC The County Council of Cecil County is the legislative branch of county government as established by the Charter - COUNCIL LEGISLATIVE SESSION of Cecil County on December 3, 2012. First and third Tuesday of month at 7:00 p.m. The County Council is composed of five council members who are elected to a four year term of office. Each Opportunity to speak during Public Comments OO Council Member is elected countywide but must reside in the district that they represent. There are five council and give testimony during public hearings on legislation manic districts in Cecil County, which has recently been redistricted to ensure an equal population in each district. Cecil County is the only Maryland county that staggers the terms of their council members. Three council Agenda available online UU members, representing districts 2,3, and 4, will be elected in 2014 during the gubernatorial election; and two Audio recording available online council members, representing districts 1 and 5, will be elected in 2016 during the presidential election. KEEP INFORMED! Access the Council website at: NN Voters elected the first County Executive in 2012 to serve a four year term of office. The role of the County - CITIZENS CORNER www.ccgov.org to get information on.. -

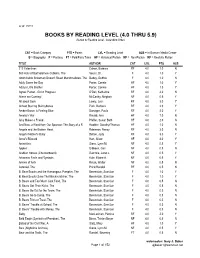

BOOKS by READING LEVEL (4.0 THRU 5.9) (Sorted by Reading Level - Ascending Order)

as of: 7/7/11 BOOKS BY READING LEVEL (4.0 THRU 5.9) (Sorted by Reading Level - Ascending Order) CAT = Book Category PTS = Points LVL = Reading Level ALB = In Burruss Media Center B = Biography F = Fantasy FT = Folk/Fairy Tales HF = Historical Fiction NF = Non-Fiction RF = Realistic Fiction TITLE AUTHOR CAT LVL PTS ALB 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara RF 4.0 1.0 N 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. F 4.0 1.0 Y Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Marshmallows, The Dadey, Debbie F 4.0 1.0 N Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie HF 4.0 1.0 Y Addy's Little Brother Porter, Connie HF 4.0 1.0 Y Agnes Parker...Girl in Progress O'Dell, Katharine RF 4.0 4.0 N Aliens are Coming! McCarthy, Meghan NF 4.0 0.5 Y All about Sam Lowry, Lois RF 4.0 3.0 Y Almost Starring Skinnybones Park, Barbara RF 4.0 3.0 Y Amber Brown Is Feeling Blue Danziger, Paula RF 4.0 2.0 Y Amelia's War Rinaldi, Ann HF 4.0 7.0 N Amy Makes a Friend Pfeffer, Susan Beth HF 4.0 2.0 N And Now, a Word from Our Sponsor: The Story of a R Hoobler, Dorothy/Thomas HF 4.0 1.0 N Angela and the Broken Heart Robinson, Nancy RF 4.0 3.0 N Angel's Mother's Baby Delton, Judy RF 4.0 3.0 Y Anna's Blizzard Hart, Alison HF 4.0 4.0 Y Antarctica Stone, Lynn M. -

Advocacy in Action: a Guide to Influencing Decision-Making In

ADVOCACY IN ACTION A guide to influencing decision-making in Namibia Gender Research and Advocacy Project LEGAL ASSISTANCE CENTRE Windhoek 2004 Updated 2007 This publication was developed with assistance and support from the following organisations: National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) through a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Women’s Legal Rights Initiative through a grant from USAID. This publication, was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS his publication was prepared by the Legal Assistance Centre with support from the Tfollowing organisations: Austrian Development Cooperation, the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) through a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Women’s Legal Rights Initiative through a grant from USAID. This manual was written by Dianne Hubbard and Delia Ramsbotham of the Legal Assistance Centre, and illustrated by Nicky Marais. The following persons provided research for the manual: Dianne Hubbard, Legal Assistance Centre Delia Ramsbotham, Legal Assistance Centre, intern through the Young Professionals International Internship Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade of Canada, coordinated through the Canadian Bar Association Maria-Laure Knapp, Legal Assistance Centre, intern in a program of Youth International Internship Programme (YIIP) of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) of Canada, coordinated through Acadia University in Canada Evelyn Zimba, Legal Assistance Centre Anne Rimmer, a Development Worker funded by International Cooperation for Development (ICD) through the Catholic Institute for International Relations (CIIR). -

Indigenous Peoples Day Toolkit

FOR OUR FUTURE AN ADVOCATE’S GUIDE TO SUPPORTING INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTIONS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...............................................................................................................................1 WHY INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY..................................................................................................................................................3 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY ACROSS THE AMERICAS ..................................................................................................................7 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY ACROSS AMERICA: CASE STUDIES AND LESSONS LEARNED .........................................................9 THE CITY OF SEATTLE’S SHIFT TOWARD INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY ........................................................................................11 HOW A MONTANA CITY AND UNIVERSITY CAME TO CELEBRATE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY ....................................................13 TRIBAL YOUTH COUNCIL BRINGS INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY TO THE STATE OF OREGON .........................................................15 HOW A NEW MEXICO REPRESENTATIVE PASSED AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY BILL IN HIS STATE ........................................17 KEY QUESTION AND ANSWERS FOR ALLIES AND ADVOCATES .....................................................................................................19 KEY MESSAGES TO ADVOCATE FOR ADOPTION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY .........................................................................22 -

2019 YIG Volunteer Book

66th Annual Tennessee YMCA YOUTH IN GOVERNMENT Sponsored by the YMCA Center for Civic Engagement April 11-14, 2019 Democracy must be learned by each generation. TABLE OF CONTENTS Conference Agenda 3-6 Letters from the Governors 7-8 Program Administration 9 YIG Delegate Roster 10-28 ABCs of YIG 29-32 2019 Election Info 33 2019 Election Ballot 34-35 Rules of Procedure 36-40 Table of Motions 41 Understanding the Committee Process 42 Format for Debate 43 How a Bill Becomes a Law 44 Legislative Glossary of Terms 45-47 Debate Script 48-49 Awards Distribution and Criteria 50 Delegate Code of Conduct 51-52 Conference on National Affairs Delegates 53 Component Leaders 54 Governor’s Cabinet 55 Lobbyists 56 Justice Frank F. Drowota Supreme Court 57 Press Corps 58 Committees 59-294 Senate 1 59-93 Senate 2 94-127 Senate 3 128-161 Senate 4 162-197 Senate 5 198-233 House 1 234-265 House 2 266-299 House 3 300-334 House 4 335-364 House 5 365-393 House 6 394-431 House 7 432-469 House 8 470-500 YIG App Download Info 501 Mail in Voter Application 503-504 2 66th Tennessee YMCA Youth in Government A Tennessee YMCA Center for Civic Engagement Program CONFERENCE AGENDA Thursday, April 11, 2019 8:00 AM Officer Meeting DT Brentwood/Franklin 8:00 – 11:00 PM Luggage storage Tennessee Ballroom Hartmann Gallery Advisor Hospitality Vanderbilt Boardroom 8:30 – 10:00 AM Conference Registration DT Ballroom Foyer 10:00- 11:00 AM Opening Session Cumberland Ballroom 11:00- 1:00 PM House Lunch Senate/Court/GovCab/Press/Lobby Meetings Senate S-1 Senate Committee 1 Salon A -

Date Printed: 06/11/2009 JTS Box Number

Date Printed: 06/11/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 74 Tab Number: 112 Document Title: The Minnesota Legislative Manual 1987-1988: Abridged Edition Document Date: 1988 Document Country: United States Minnesota Document Language: English 1FES 1D: CE02344 The Minnesota Legislative Manual 1987-1988: Abridged Edition fl~\~:1~1,3~1---~. ELECTION AND LEGISLATIVE MANUAL DlVISION·%~:j'.:~. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE . ~J;.;: ..... ~~\?- 180 STATE OFFICE BUILDING. ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 55155.612-296-2805 .185S The Minnesota Legislative Manual 1987-88: Abridged Edition 2 Contents The Perspective of Minnesota's Governors. .. 3 The Minnesota Legislature ..................................... 11 Members ofthe Legislature .................................... 15 Enactment of Legislation ...................................... 17 How a Bill Becomes a Law ..................................... 19 Legislative District Maps ....................................... 20 Legislative Committees ........................................ 22 Constitutional Officers ........................................ 28 Executive Officers Since Statehood ............................ 34 Minnesota's Changing Population .............................. 37 Minnesota In Profile ........................................... 37 Minnesota Symbols ........................................... 38 Minnesota Chronicle .......................................... 39 Fundamental Charters and Laws ............................... 43 Minnesota Constitution ........................................ 46 Minnesota -

August Quiz List by Author.Pdf

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Friday, August 20, 2010 12:31:07PM School: Chattahoochee Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 17504 EN Anansi Does the Impossible! An Aardema, Verna LG 3.2 0.5 1,277 F Ashanti Tale 7659 EN Borreguita and the Coyote Aardema, Verna LG 3.1 0.5 832 F 9758 EN Bringing the Rain to Kapiti Plain Aardema, Verna LG 4.6 0.5 717 F 46144 EN Koi and the Kola Nuts: A Tale from Aardema, Verna LG 4.0 0.5 1,599 F Liberia 76201 EN Oh, Kojo! How Could You! An Aardema, Verna LG 3.4 0.5 1,757 F Ashanti Tale 73785 EN Rabbit Makes a Monkey of Lion: A Aardema, Verna LG 3.3 0.5 1,333 F Swahili Tale 27104 EN Who's in Rabbit's House? Aardema, Verna LG 2.8 0.5 1,464 NF 5550 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Aardema, Verna LG 4.0 0.5 1,219 F Ears: A West African Tale 913 EN Conejito Velloso, El Aargent, Dave/Pat U 1.3 0.5 182 F 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan MG 7.9 2.0 12,708 F 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan MG 7.4 2.0 11,404 F 15652 EN Meat-Eating Plants Aaseng, Nathan MG 6.8 1.0 5,734 NF 8480 EN Navajo Code Talkers Aaseng, Nathan UG 9.5 4.0 20,971 NF 900503 EN Life in Flatland (MH) Abbott, Edwin MG 5.2 0.5 2,099 F 65672 EN Magic Escapes, The Abbott, Tony MG 3.7 2.0 16,966 F 62264 EN Moon Scroll, The Abbott, Tony MG 3.7 2.0 13,345 F 54503 EN Under the Serpent Sea Abbott, Tony MG 3.6 2.0 11,398 F 89665 EN Voyagers of the Silver Sand Abbott, Tony MG 4.1 3.0 19,700 F 78108 EN Wizard or Witch? Abbott, Tony MG 3.3 -

Downloaded and Analyzed Using a Statistical Software

Copyright © 2010 by the National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) in partnership with the American Academy of Pediatrics and the California Medical Association Foundation Pilot Version, May 6, 2010 All rights reserved. Individuals and organizations participating in this training may reproduce any of these materials but solely for the purpose of training within their organizations. Any such reproduction should include an acknowledgement as follows: Reproduced, with permission, from the Be Our Voice: Mobilizing Healthcare Professionals as Community Leaders in the Fight Against Childhood Obesity, Advocacy Resource Guide, copyrighted by the National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality. No other reproduction is authorized without the written permission of the copyright holder. This work is sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Write to: National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality 30 Winter Street, 6th Floor Boston, MA 02108-4720 (617) 391-2700 [email protected] Mobilizing Healthcare Professionals in the Fight Against Childhood Obesity | Advocacy Resource Guide |May 2010 2 January 2010 Nearly one-third of children and adolescents are overweight or obese. This epidemic is taking its greatest toll on children living in underserved communities. Many of these children are developing diseases that until now were only seen in adults, including type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Their weight is putting them at a disproportionate risk for heart disease, stroke, and cancers. Each time you see the toll this epidemic is taking, it probably feels overwhelming. It is frustrating to spend time educating families about the importance of physical activity only to hear local schools have slashed time outside the classroom. -

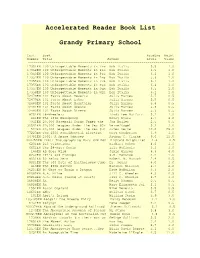

Accelerated Reader Book List Grandy Primary School

Accelerated Reader Book List Grandy Primary School Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17351EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 5.5 1.0 17352EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.5 1.0 17353EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.2 1.0 17354EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 5.6 1.0 17355EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.1 1.0 17356EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.4 1.0 17357EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Sum Bob Italia 6.5 1.0 17358EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Win Bob Italia 6.1 1.0 72478EN 101 Facts About Deserts Julia Barnes 5.7 0.5 72479EN 101 Facts About Lakes Julia Barnes 5.5 0.5 72480EN 101 Facts About Mountains Julia Barnes 5.4 0.5 72481EN 101 Facts About Oceans Julia Barnes 5.8 0.5 72482EN 101 Facts About Rivers Julia Barnes 5.3 0.5 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Jon Buller 2.5 0.5 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Gr Verne/Vogel 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 77223EN The 2000 Presidential Election Cory Gunderson 6.9 1.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 9.0 12.0 900355EN 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edi Richard Brightfiel 4.6 0.5 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4.0 1.0 6651EN The 24-Hour Genie Lila McGinnis 3.3 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. -

POLS 4950: Knope, Swanson, and Public Service

POLS 4950: Knope, Swanson, and Public Service Dr. Keith E. Lee Jr. July 2019 E-mail: [email protected] Web: keitheleejr.com Office Hours: by appointment (phone or WebEx) Class Hours: online Office: online Class Room: online Course Description1 This course uses the NBC sitcom Parks & Recreation to explore the concepts of traditional public administration, new public management, and what Denhart and Denhart refer to as the new pub- lic service. The traditional public admin model evolved dramatically in the 1980s and 1990s. The new model, New Public Management, approached public service as a business and used private sector strategies to improve efficiency. New Public Service provides a competing approach that calls for a reaffirmation of public values that puts public interest first. Leslie Knope embodies the new public service and works tirelessly to meet citizen needs. Ron Swanson, on the other hand, is an anti-government libertarian that challenges Knope’s attempts to grow government to serve citizens, arguing government is the problem. Chris Traeger and Ben Wyatt exemplify new public management principles when they show up in Pawnee to conduct an audit. Course Readings The book required for this course is available online via the library. Use this link to access the book: The New Public Service Bozeman’s Public Values and Public Interest is recommended to students interested in a more theo- retical challenge to New Public Management. Course Objectives By the end of the semester you will be able to: • Differentiate between New Public Service, New Public Management, and Old Public Ad- ministration • Examine various scenarios and apply concepts from the text 1I reserve the right to make changes to this syllabus at any time. -

Guide to Participating in Legislature (Booklet)

Legislative Information Center 07-13-2021 THE WASHINGTON STATE LEGISLATURE Washington has a bicameral legislature of members of the House both during which convenes in regular session annu- the duration of session and the interim ally. Regular sessions begin the second between sessions. In the event of illness, Monday in January of each year and are death, or inability to act, the Speaker constitutionally limited to 105 days dur- Pro Tempore, who is also elected at the ing odd numbered years and 60 days in commencement of each regular session even years. Special sessions are called shall hold office during all sessions until by the Governor’s proclamation in which the convening of the succeeding regular reason for the call must be stated, or by a session. two-thirds vote of the Legislature. Chief Clerk: The Chief Clerk of the The Senate has 49 members and there House, like the Secretary of the Senate, are 98 representatives in the House. Dis- is an administrative officer. Neither is a tricts from which legislators are elected member of the Legislature, but both are are subject to redistricting and reappor- the Senate; has charge of and sees that elected by the bodies. The Chief Clerk tionment on the basis of population after all officers, attaches, and clerks perform selects and removes employees with each decennial census. their duties. These duties are prescribed approval of the Speaker of the House, State Representatives are elected to a by rules of the Senate, and pass, in the supervises preparation of the journal, two-year term and all Representatives absence of the President, to the Presi- performs other duties of this office, and stand for re-election at the general elec- dent Pro Tempore, who is elected by is responsible at all times for the acts of tion held in even-numbered years.