Big Five Personality Traits in Team Sport 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix a – National and Local Recreation Trends

APPENDIX A – NATIONAL AND LOCAL RECREATION TRENDS NATIONAL DATA NATIONAL TRENDS IN GENERAL SPORTS The sports most heavily participated in for 2016 were golf (24.1 million in 2015) and basketball (22.3 million), which have participation figures well in excess of the other activities in the general sports category. The popularity of golf and basketball can be attributed to the ability to compete with relatively small number of participants. Golf also benefits from its wide age segment appeal, and is considered a life-long sport. Basketball’s success can be attributed to the limited amount of equipment needed to participate and the limited space requirements necessary, which make basketball the only traditional sport that can be played at the majority of American dwellings as a drive-way pickup game. Since 2011, rugby and other niche sports, like boxing, roller hockey, and squash, have seen strong growth. Rugby has emerged as the overall fastest growing sport, as it has seen participation levels rise by 82.4% over the last five years. Based on the five-year trend, boxing (62%), roller hockey (55.9%), squash (39.3%), lacrosse (39.2%), cheerleading (32.1%) and field hockey (31.8%) have also experienced significant growth. In the most recent year, the fastest growing sports were gymnastics (15%), rugby (14.9%), sand volleyball (14.7%), Pickleball (12.3%), and cheerleading (11.7%). During the last five years, the sports that are most rapidly declining include touch football (-26%), ultimate Frisbee (-24.5%), racquetball (-17.9%), and tackle football (-15%). Ultimate Frisbee and racquetball are losing their core participants while touch football and tackle football are experiencing attrition of its casual participant base. -

Rules Or Coeducational Activities and Sports

SP 011 TXTLE Rulesor Coeducational Activities and Sports. SlItUTION American Alliance for Health, Physical Educatio,n, and ReAeation, Washington, D.C.; American AllianCe for Hellth, PhysicAl Education, and RecNation, ,Washington, D.C. National Association for Girls and Women lin Sport.; American Alliance for Health, Rhysical Education, and,Recreation, Washington, D-C, Nationaf Association for Sport and Physical* Education. PUB k'r r 77 . NOTE 40p. AVAILABLE FEW! American Alliance for HealthPhysical Educati n and Recreation, 1201 16th Street N.w., Washington, D.c. 20036 ($2.50) EDRS PRICE MY-$6.83 'Plus Postage. HC Not- Available--from:EDRS.. DESCRITTORS -*Athletics;. *CoeducatiOn;..,Cellige Students; Higher, Education; *intramural Athletic. PrograMs;..PhySiCal' Education; *PhySical-Recieation Programs; Soccer': Volleyball; .Womens AthleticS , ABSTRA T Suggestidns and. guidelines for e stab ishing'rules for . co-recreational, . intramural aativities,are presented. These rtIes are- mot inteMdedas a _precedent,or a. national standard-- hey are-ideas ,for adaqing standardized-rules-for,men's and wo-Men,-sports to. Meet ,the nee .0 demands, and characteristics Of coreCreat_onalsports Eleven 4 f;erent c011ege-levelactivities are-deScrib A al.ong with sa4geStiOnstl for modification of collegelettel sports/. Ipr elementary and-seccMary levels. Rules are presented for basketba. h' -broombarl, flag football, hoop hockey, innertube waterpoloi slow pitch,softball1 soccer, tug championships, frisbee, and volleyball.. '(MI) ********** **************** ************************ **************p* ,06cuments acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available frOm other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the.hest copy-avaikahle. Nevertheless, items of.marginal * * reprod-ucibili4y are often encountered and this affects the quality * of ths' microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERI: makes available * via the ERIC Document Reprodlaction Servi4P, (EDR5). -

Englewood Public School District Physical Education Grade 7

Englewood Public School District Physical Education Grade 7 Unit 4: Speedball, Ultimate Frisbee, and Softball Overview: Physical fitness and motor skills will be emphasized through games and sports, such as speedball, ultimate frisbee and softball. Team work will be emphasized as students learn to cooperate and communicate with their peers. Coordination and body awareness are also engaged as students develop lifelong fitness habits. Time Frame: One Marking Period Enduring Understandings: Understanding how critical aerobic exercise is to the overall health of an individual. Body awareness and coordination are necessary components of a well-grounded individual. Cooperation within a team/group is necessary for success in all areas. Students will learn how to incorporate team strategy and cooperation into real life situations and also learn why it is considered a lifelong recreational sport. Students learn the basic skills and rules of the game of softball and how to apply it into a lifelong recreational activity. Essential Questions: What components of fitness does speedball encompass? How does team handball increase the fitness level of each individual? How does working on a team help improve cooperation skills? What components of fitness does Ultimate Frisbee encompass? How does team handball increase the fitness level of each individual? How does working on a team help improve cooperation skills? What are the basic skills and rules for the game of softball? Standards Topics and Objectives Activities Resources Assessments Comprehensive Health Topics Equipment: Formative: and Physical Education • Hockey nets • Teacher-Student Speedball Students will read an • Gator skin ball/indoor Observations 2.5.8.A.1 article about the soccer ball • Level of skills and Explain and Objectives profession of personal • Scoreboard improvement through demonstrate the training. -

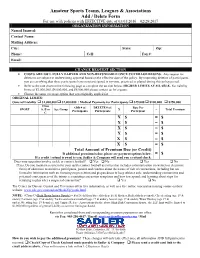

Amateur Sports Teams, Leagues & Associations Add / Delete Form

Amateur Sports Teams, Leagues & Associations Add / Delete Form For use with policies with EFFECTIVE date of 03/01/2016 – 02/28/2017 ORGANIZATION INFORMATION Named Insured: Contact Name: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: Phone: Cell: Fax #: Email: CHANGE REQUEST SECTION • COSTS ARE 100% FULLY EARNED AND NON-REFUNDABLE ONCE COVERAGE BEGINS. Any request for deletions are subject to underwriting approval based on the effective date of the policy. By requesting deletion of participants, you are certifying that these participants have not participated in try-outs, practiced or played during this policy period. • Refer to the rate chart on the following page to complete the section below. HIGHER LIMITS AVAILABLE- For liability limits of $3,000,000, $4,000,000, and $5,000,000 please contact us for a quote. • Choose the same coverage option that you originally applied for. ORIGINAL LIMITS: General Liability $1,000,000 $2,000,000 / Medical Payments for Participants $25,000 $100,000 $250,000 Class ADD # of: DELETE # of: Rate Per SPORT A, B or Age Group X = Total Premium Participants Participants Participant C X $ = $ X $ = $ X $ = $ X $ = $ X $ = $ X $ = $ Total Amount of Premium Due (or Credit) If additional premium is due, please see payment options below. = $ If a credit / refund is owed to you, Sadler & Company will send you a refund check. Does your operation involve tackle or contact football? Yes No Yes No If yes, Do you maintain a system for your tackle/contact football activities that includes communication (in written or electronic -

National Trends

APPENDIX B – NATIONAL TRENDS TRENDS ANALYSIS Information released by Sports & Fitness Industry Association’s (SFIA) 2016 Study of Sports, Fitness, and Leisure Activities Topline Participation Report reveals that the most popular sport and recreational activities include: fitness walking, treadmill, running/jogging, free weights and road bicycling. Most of these activities appeal to both young and old alike, can be done in most environments, are enjoyed regardless of level of skill, and have minimal economic barriers to entry. These popular activities also have appeal because of their social application. For example, although fitness activities are mainly self-directed, people enjoy walking and biking with other individuals because it can offer a degree of camaraderie. Fitness walking has remained the most popular activity of the past decade by a large margin, in terms of total participants. Fitness walking participation last year was reported to be nearly 110 million Americans. Although fitness walking has the highest level of participation, it did report a 2.4% decrease in 2015 from the previous year. This recent decline in fitness walking participation paired with upward trends in a wide variety of other activities, especially in fitness and sports, suggests that active individuals are finding new ways to exercise and diversifying their recreational interests. In addition, the popularity of many outdoor adventure and water-based activities has experienced positive growth based on the most recent findings; however, many of these activities’ rapid increase in participation is likely a product of their relatively low user base, which may indicate that these sharp upward trends may not be sustained long into the future. -

Hazleton Area School District District Unit/Lesson Plan

HAZLETON AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT DISTRICT UNIT/LESSON PLAN Teacher Name: Nick Bellanco Subject: Physical Education Start Date(s): 5/16/2017 Grade Level (s): 10th Building: Hazleton Area High School End Date (s): Click here to enter a date. Unit Plan Unit Title: Recreational Games: This 11 day unit will involve multiple physical education activities that require teamwork, strategy, motor skills, and an understanding of knowledge for the different types of games within the unit. Essential Questions: How do good teammates interact with others? What must participants do to show good sportsmanship? How does utilizing certain strategies affect a game? How does understanding the rules to a game affect your performance? What is the role of the captain of the team? Standards: PA Core Standards, PA Academic Standards/Anchors (based on subject) PHYSICAL ACTIVITY 10.4 A. Physical Activities That Promote Health and Fitness F. Physical Activity and Group Interaction CONCEPTS, PRINCIPLES, AND STRATEGIES OF MOVEMENT 10.5 B. Motor Skill Development F. Game Strategies ANCHOR M 11.B 2.2 Use and/ or determine or describe measures of perimeter, circumference, area, or volume. Summative Unit Assessment : Students will be graded by teacher observation on their daily participation, preparedness, and effort put forth on the different activities and also a written test on each game in the unit. Summative Assessment Objective Assessment Method (check one) Students will be able to work together ☐Rubric ☐ Checklist ☒ Unit Test ☐ Group safely on teams while using strategies of ☐ the activities they are participating in. Student Self-Assessment ☒Other (explain) Teacher Observation & Student Particiaption DAILY PLAN Da DOK Materials / Objective (s) Activities / Teaching Strategies Assessment of Objective (s) y LEVEL Resources Grouping Students will be able to Capture the Flag- I will break the class into 2 teams. -

Australian Ultimate Page 3 Welcome

Australian AUUltimate October Two Thousand and Two Winter’s Over! Summer at Last! Newsletter of the Australian Flying Disc Association Inc Page 2 Contacts Australian Flying Disc Tasmainan Flying Disc New South Wales Flying Disc Association Inc Association Association Inc PO Box A1086 Email inquiries: PO Box A1086 Sydney South NSW 1235 [email protected] Sydney South NSW 1235 [email protected] Queensland Ultimate Disc President - Simon Farrow [email protected] President - Jonathan Potts Association [email protected] Treasurer - Lisa Waters Treasurer - Tom Brennan [email protected] [email protected] President - Matt Boevink Secretary - Liz Blink [email protected] ACT Ultimate Association [email protected] Communications Officer - Emma Spranklin Chair of Selectors - Simon Wood [email protected] GPO Box 842 [email protected] Canberra ACT 2601 National Events Director - Ashley Scroggie Victorian Flying Disc [email protected] Association President - Catherine Moyle Newsletter Editors - Jason de Rooy and [email protected] Shannon Wandmaker PO Box 549 Treasurer - Anthony Perry [email protected] Collins St West [email protected] Universities Co-ordinator - Martin Laird Melbourne 8007 [email protected] Got Something to Say? Insurance Officer - Colin Wagstaff Email inquiries: [email protected] [email protected] Anti-Doping Officer - John French President - Paul Egan Do you have any news, photo’s, [email protected] [email protected] competition reports or competition Treasurer - Simon Gorr previews you’d like to share? Western Australian Flying Disc [email protected] Association Maybe you have some tips on tactics, Northern Territory Ultimate nutrition, fitness or beer. -

WFDF Board Meeting Minutes January 19-20, 2019 Hilton Garden Inn Queens at JFK Airport, New York, USA

WFDF Board Meeting Minutes January 19-20, 2019 Hilton Garden Inn Queens at JFK Airport, New York, USA Saturday, January 19, 2019 Board of Directors members present: Robert “Nob” Rauch (chair), Kate Bergeron, Thomas Griesbaum, Brian Gisel, Charlie Mead, Steve Taylor, Kevin Givens, Karen Cabrera, Jamie Nuwer, Caroline Malone, Ali Smith, Rob McLeod, Jesus Loreto, Amandine Constant, Yoonee Jeong, Travis Smith. Board of Directors members absent: Fumio Morooka, Alex Matovu. Staff (non-voting) also attending: Volker Bernardi (WFDF Executive Director), Karina Woldt (WFDF Event Manager), Tim Rockwood (WFDF Managing Director Broadcasting), Gabriele Sani (Director of Development). The quorum was reached with 16 Board members out of 18 present. Welcome and Opening: President Rauch welcomed all participants at 8:18am and thanked the participants for traveling to New York. All attendees gave a short introduction of themselves. Responsibilities as a WFDF Board member Rauch noted that WFDF had so many new board members that he wanted to provide a guideline to what it means to be on the WFDF Board. Some of the duties mentioned were attendance of board conference calls, timely responses to e-mail correspondence and electronic votes, reading all briefing book materials, approving tournament hosts, new member applications and contracts, and maintaining familiarity with and following disc sports news and social media. He reminded that everything a board member does or comments on reflects on WFDF and the board and might affect partners of WFDF. Board members should support decisions made even if they personally disagree. They should follow the WFDF Code of Ethics such as equality and dignity, integrity, good governance and confidentiality. -

Organizer's Manual

TWG Cali 2013 Organizer’s Manual Artistic & Dance Ball Sports Martial Arts Precision Strength Trend Sports Sports Sports Sports INDEX IF Commitment 5 History 6 Sports by Cluster 10 Artistic & DanceSports 13 Acrobatic Gymnastics 15 Aerobic Gymnastics 19 Artistic Roller Skating 23 DanceSport 27 Rhythmic Gymnastics 31 Trampoline 35 Tumbling 39 Ball Sports 43 Beach Handball 45 Canoe Polo 49 Fistball 53 Korfball 57 Racquetball 61 Rugby 65 Squash 69 Martial Arts 73 Ju-jitsu 75 Karate 79 Sumo 83 Precision sports 87 Sports of TWG2013 as of 21.07.2013 Page 2 Billiard Sports 89 Boules Sports 95 Bowling 101 World Archery 105 Strength sports 109 Powerlifting 111 Tug of War 115 Trend Sports 119 Air Sports 121 Finswimming 125 Flying Disc 129 Roller Inline Hockey 133 Life Saving 137 Orienteering 141 Speed Skating 145 Sport Climbing 149 Waterski & Wakeboard 153 Invitational sports 159 Canoe Marathon 161 Duathlon 165 Softball 169 Speed Skating Road 173 Wushu 177 Schedule 180 Contact 185 Page 3 Sports of TWG2013 as of 21.07.2013 Page 4 IF COMMITMENT International Sports Federations The IWGA Member International Sports Federations ensure: The IWGA Member International Sports Federations ensure the participation of the very best athletes in their events of The World Games by establishing the selection and qualification criteria accordingly. Together with the stipulation for wide global representation of these athletes, the federations’ commitment guarantees top-level competitions with maximum universality. As per the Rules of The World Games, federations present their events in ways that allow the athletes to shine while the spectators are well entertained. -

Insurance Program and Enrollment Form This Brochure Is Valid for Effective Dates from 3/1/16 Through 2/28/17 Receive

AMATEUR SPORTS TEAMS, LEAGUES AND ASSOCIATIONS Insurance Program and Enrollment Form This brochure is valid for effective dates from 3/1/16 through 2/28/17 Receive PROGRAM DESCRIPTION ELIGIBLE OPERATIONS This program has been designed for U.S.-based teams, Organizations providing instruction, practice and competition in leagues, clubs and associations conducting youth or adult the following sports and age groups are eligible for this program, amateur sports activities. Coverage provided includes with coverage to be provided based on Class A, Class B, or important liability protection for the organization, including its Class C classifications. employees and volunteers, for liability claims arising out of its operations. For eligible sports and age groups reported to Note: 1. If your sport is not listed, contact us for proper us, covered operations consist of your scheduled, sanctioned, classification. approved, organized and supervised practices, try-outs, clinics, 2. If you have Class A, Class B and/or Class C games, playoffs and tournaments in which you participate participants on the same team, you must use the or host. Coverage is also provided for your registrations, Class A rate for all participants (Class A coverage meetings, concession stand operations, parades in which option will apply). you participate, picnics, award banquets and ceremonies and 3. For Class C Sports you have the option to exclude incidental fund-raising activities involving the sale of products, coverage for brain injuries. coupons, raffle tickets and services, such as: car washes, bake sales and coin drops, for those sports and age groups reported Class A Sports: to us. • Box lacrosse • Lacrosse (age 20 & over) • Broomball • Roller hockey (inline) Coverage is provided by a carrier rated A+ (Superior) by A.M. -

Recreation & Fitness

Student Life Recreation & Fitness On-campus opportunities Our 278,000-square-foot University Recreation Center (UREC) is incredible. jmu.edu/recreation n Special features includes multiple climbing walls, seven racquetball courts, three multi-activity gyms, two indoor tracks, a 25,000-square-foot cardio theatre and fitness center, an indoor aquatics center, an adventure center, locker rooms, a wellness suite, an equipment center, two outdoor courtyards and six group exercise studios. n In addition to gym and fitness spaces, UREC also features a dining facility, a meditation room, a dining facility, batting cages, massage studios, as well as personal training, fitness assessment and athletic training rooms. Wellness is more than just fitness Here are some other special touches we have available for our students: n Personal training sessions and fitness assessments can help you get started on the right foot or break through to the next level. n A top–notch nutritionist can help you meet your fitness goals in a healthy, manageable way that will set you up for the rest of your life. n Massage Therapists can help you maintain your peak performance condition or de-stress before exams. n University Park and lots of other amazing outdoor recreation spaces must be experienced to be believed. Activities in the Shenandoah Valley The four distinct seasons of the year that we experience in Virginia offer an abundance of opportunities for recreational variety. Winter may find you zipping down the ski slopes, or tubing at nearby Massanutten Resort or one of the other popular ski resorts within an hour drive from campus. -

SODA Amateur Sports Insurance Program Teams, Leagues & Tournaments (Youth & Adult) Available 01-01-2021 to 12-31-2021

SODA Amateur Sports Insurance Program Teams, Leagues & Tournaments (Youth & Adult) Available 01-01-2021 to 12-31-2021 In our continuing efforts to be recognized as “the organization” devoted to the advancement of recreational Become an affiliate member of SODA and qualify for sports facilities, SODA is again proud to offer many insurance program options. Prices shown include benefits, as well as, the SODA Amateur Sports Membership affiliate membership fees and insurance rates. Insurance Program. Amateur sports teams and leagues - both adult and youth - in the sports listed below are The SODA Insurance Program combines broad eligible to participate in this national program. We also coverages, highly competitive prices, and exemplary offer coverages for tournaments, youth camps & clinics, service in terms of processing paperwork, answering sports officials and field owners for the sports referenced questions and claims administration. at the bottom of this page. NATIONAL SPORTS ASSOCIATIONS POOL Many regional and national sports associations don’t have the “buying power” to negotiate the most favorable discounts on products, coverages and prices for their own insurance programs. As a result, SODA welcomes such organizations to join SODA and p articipate in the SODA insurance program for the benefit of their members. SODA MEMBER ENDORSEMENTS FOR 2020 AAABA - Adult Baseball Leagues ABA Sports Leagues, Inc. All American Amateur Baseball All American Sports Chinese Christian Union Leagues (CCUL) The Epic Center GRADA - Disc Golf Association IAAA Basketball Assoc. KIX – National Kickball Leagues. Long Island Tennis & Sports Foundation Maryland Softball Assoc. Mills Ponds Umpires Association (MPUA) N. American Fast-Pitch Assoc. National Amateur Sports Federation National Association of Sports Coaches (NASC) National Fast Pitch Softball Assoc.