Pdf, 945.96 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WCZESNOŚREDNIOWIECZNY GRÓD W ŁAPCZYCY, POW. BOCHNIA, W ŚWIETLE BADAŃ LAT 1965—1967 I 1972

Sprawozdania Archeologiczne, t. XXVI, 1974 ANTONI JODŁOWSKI WCZESNOŚREDNIOWIECZNY GRÓD W ŁAPCZYCY, POW. BOCHNIA, W ŚWIETLE BADAŃ LAT 1965—1967 i 1972 WSTĘP W Łapczycy położonej w odległości 4 km w kierunku zachodnim od Bochni, na prawym brzegu Raby znajduje się grodzisko usytuowane na wzniesieniu o na- zwie „Grodzisko" (ryc. 1—2). Jest to jeden z cyplowatych występów pasma wznie- sień, ciągnącego się równoleżnikowo od miejscowości Chełm — a ściślej od potoku Moszczenickiego — na zachodzie po Bochnię na wschodzie, stanowiącego granicę między Pogórzem Karpackim a Kotliną Sandomierską. Grodzisko leży na północnym stoku owego grzbietu, znacznie poniżej jego kulminacji i ograniczone jest od pół- nocy, północnego zachodu oraz północnego wschodu doliną Raby, która dawniej prze- pływała bezpośrednio u jego podnóża (obecnie koryto rzeki znajduje się w odle- głości 230 m na północ). Od południa i południowego wschodu zbocza grodziska opadają stromo do małej doliny z wysychającym okresowo niedużym strumykiem bez nazwy, natomiast od strony zachodniej i południowo-zachodniej, gdzie teren wznosi się łagodnie ku południowi, obiekt oddzielony był od pozostałej części wzgó- rza naturalnym obniżeniem, pogłębionym sztucznie w celu zwiększenia obronności. Wschodnia partia grodziska zniszczona została częściowo przez wybieranie gliny, majdan zaś, zbocze zachodnie i podgrodzie zajęte są pod uprawę, która spowodo- wała silne zniwelowanie wałów. Pierwotną formę i rozmiary grodu wyznaczają naturalne załomy zboczy oraz zachowane miejscami fragmenty umocnień obronnych. Wskazują one, że gród skła- dał się z dwóch części: z grodu właściwego w kształcie nieregularnego owalu zbliżonego do wieloboku o wym. 96 X 58 m, tj. 55,68 ara, wydłużonego wzdłuż osi NE—SW (ryc. 3), i czworobocznego podgrodzia o powierzchni 60,9 ara (105 X 58 m), przylegającego do grodu od strony północno-wschodniej. -

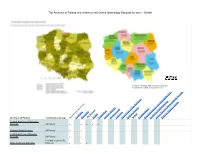

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

Polskaakademianauk Instytutpaleobiologii

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK INSTYTUT PALEOBIOLOGII im. Romana Kozłowskiego SILURIAN AND DEVONIAN HETEROSTRACI FROM POLAND AND HYDRODYNAMIC PERFORMANCE OF PSAMMOSTEIDS Sylurskie i dewońskie Heterostraci z Polski oraz efektywność hydrodynamiczna psammosteidów Marek Dec Dissertation for degree of doctor of Earth and related environmental sciences, presented at the Institute of Paleobiology of Polish Academy of Sciences Rozprawa doktorska wykonana w Instytucie Paleobiologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk pod kierunkiem prof. dr hab. Magdaleny Borsuk-Białynickiej w celu uzyskania stopnia doktora w dyscyplinie Nauki o Ziemi oraz środowisku Warszawa 2020 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………….….... 3 STRESZCZENIE………………………………………………………………….....….. 4 SUMMARY……………………………………………………………………….…….. 8 CHAPTER I…………………………………………………………………………….. 13 TRAQUAIRASPIDIDAE AND CYATHASPIDIDAE (HETEROSTRACI) FROM LOWER DEVONIAN OF POLAND CHAPTER II……………………………………………………………………….…… 24 A NEW TOLYPELEPIDID (AGNATHA, HETEROSTRACI) FROM THE LATE SILURIAN OF POLAND CHAPTER III…………………………………………………………………………... 41 REVISION OF THE EARLY DEVONIAN PSAMMOSTEIDS FROM THE “PLACODERM SANDSTONE” - IMPLICATIONS FOR THEIR BODY SHAPE RECONSTRUCTION CHAPTER IV……………………………………………………………………….….. 82 NEW MIDDLE DEVONIAN (GIVETIAN) PSAMMOSTEID FROM HOLY CROSS MOUNTAINS (POLAND) CHAPTER V……………………………………………………………………………109 HYDRODYNAMIC PERFORMANCE OF PSAMMOSTEIDS: NEW INSIGHTS FROM COMPUTATIONAL FLUID DYNAMICS SIMULATIONS 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost I would like to say thank you to my supervisor Magdalena -

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust

THE POLISH POLICE Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski The Polish Police Collaboration in the Holocaust Jan Grabowski INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE NOVEMBER 17, 2016 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jan Grabowski THE INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. Wrong Memory Codes? The Polish “Blue” Police and Collaboration in the Holocaust In 2016, seventy-one years after the end of World War II, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminated a long list of “wrong memory codes” (błędne kody pamięci), or expressions that “falsify the role of Poland during World War II” and that are to be reported to the nearest Polish diplomat for further action. Sadly—and not by chance—the list elaborated by the enterprising humanists at the Polish Foreign Ministry includes for the most part expressions linked to the Holocaust. On the long list of these “wrong memory codes,” which they aspire to expunge from historical narrative, one finds, among others: “Polish genocide,” “Polish war crimes,” “Polish mass murders,” “Polish internment camps,” “Polish work camps,” and—most important for the purposes of this text—“Polish participation in the Holocaust.” The issue of “wrong memory codes” will from time to time reappear in this study. -

Wójt Gminy Kłaj Studium Uwarunkowań I Kierunków

Załącznik Nr 1 do uchwały Nr … Rady Gminy Kłaj z dnia … r. WÓJT GMINY KŁAJ STUDIUM UWARUNKOWAŃ I KIERUNKÓW ZAGOSPODAROWANIA PRZESTRZENNEGO GMINY KŁAJ USTALENIA STUDIUM projekt – wyłożony ponownie do publicznego wglądu w okresie od 07.01.2019 r. do 31.01.2019 r. Kłaj, 2017-2019 r. Studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego Gminy Kłaj Organ sporządzający studium: Wójt Gminy Kłaj 32-015 Kłaj 655 Jednostka opracowująca projekt studium: Pracownia Projektowa Architektury i Urbanistyki – Jacek Banduła 30-081 Kraków, ul. Królewska 69/38 tel./fax 12 6367378, 668482010 [email protected] Zespół projektowy: mgr inż. arch. Jacek Banduła - główny projektant, kierownik zespołu uprawnienia urbanistyczne nr RP-upr. 5/93, członek i rzeczoznawca b. Polskiej Izby Urbanistów mgr Maciej Sybilski - współpraca projektowa mgr inż. arch. Paweł Migut - współpraca projektowa mgr inż. Magdalena Banduła - współpraca projektowa dr hab. Dorota Matuszko - zagadnienia ochrony środowiska Mariusz Kamiński - współpraca, opracowanie graficzne Opracowanie: Pracownia Projektowa Architektury i Urbanistyki - 2017-2019 r. 1 Studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego Gminy Kłaj SPIS TREŚCI I. WPROWADZENIE .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. Podstawy prawne opracowania ....................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Charakter i zawartość opracowania ............................................................................................... -

Protected Areas of the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship

Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Vol. 30 No 3(81): 35-46 Ochrona Środowiska i Zasobów Naturalnych DOI 10.2478/oszn-2019-0016 Dariusz Wojdan*, Ilona Żeber-Dzikowska*, Barbara Gworek**, Katarzyna Mickiewicz ***, Jarosław Chmielewski**** Protected areas of the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship * Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach, ** Szkoła Główna Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego w Warszawie, *** Instytut Ochrony Środowiska - Państwowy Instytut Badawczy w Warszawie **** Wyższa Szkoła Rehabilitacji w Warszawie; e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, protection areas, natural objects, conservation Abstract The Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship is one of the smallest provinces in Poland, but it clearly stands out with a very well-preserved natural environment. Because of exceptional features of animate and inanimate nature, large parts of the province are covered by various forms of nature protection. There is 1 national park (NP), 72 nature reserves (NRs), 9 landscape parks, 21 protected landscape areas and 40 Natura 2000 sites within the administrative borders of the province. The most unique natural features are found in the Świętokrzyski National Park (ŚNP), but the largest surface of the province is covered by protected landscape areas. Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship is the first in Poland in terms of the share of protected areas (as much as 65.2%), strongly outdistancing other Voivodeships. Small natural objects are much more numerous than large protected areas. At present, the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship has 705 natural monuments (NMs), 114 ecological sites (ESs), 20 documentation sites (DSs) and 17 nature and landscape complexes (NLCs). Moreover, new protected areas and sites may still be established within its borders. © IOŚ-PIB 1. INTRODUCTION [Polish Journal of Laws 2004, no. -

By Julius A. Kolatschek Translation of Chapter 12 (Pages 146 to 191) by Hieke Wolf

Die evanglisch Kirche Oesterreichs in den deutsch-slavischen (The Evanglical Church of Austria in German-Slavic Areas) by Julius A. Kolatschek Translation of Chapter 12 (Pages 146 to 191) by Hieke Wolf Abbreviations: A. B. Augsburg Denomination D. Diaspora F. Branch fl. Florin (also called a Gluden) (1 Florin = 60 Kreutzer) G.A.V. Gustav Adolf Association Gr. Foundation H.B. Helvetian Denomination Kon. Constitution kr. Kreutzer (1 Florin = 60 Kreutzer) L.P. Last Post S. School Community Sel. Number of Souls (inhabitants) Statsp. Government lump sum Ter. Territory XII. Galicia We first want to give a few explanations in order to improve understanding for the special conditions of Galicia's protestant parishes. The protestant parishes of Galicia are exclusively German parishes and have mainly emerged from the country's colonization carried out by Empress Maria Theresia and Emperor Josef II in the second half of the last century. Immigrants mainly came from South Germany. Protestant colonists received considerable rights and privileges through the patents of October 1, 1774 and September 17, 1781. One to mention before all others is the „ Freie Religions Exercitium “ (free practice of religion), at first only in the cities Lemberg, Jaroslau, Brody, Zamosc and Zaleßezyki, later „without any restriction to this or that location“ in the whole country, with the rights to build prayer houses and churches, as well as the appointing and employing of pastors. In the cities gratuitous bestowal of citizens' rights 1 and right to possession 2. Furthermore exemption from all personal taxes and dues, at first for 6, then for 1 Not every citizen automatically had citizens' rights (mainly rights to vote). -

Nihil Novi #3

The Kos’ciuszko Chair of Polish Studies Miller Center of Public Affairs University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia Bulletin Number Three Fall 2003 On the Cover: The symbol of the KoÊciuszko Squadron was designed by Lt. Elliot Chess, one of a group of Americans who helped the fledgling Polish air force defend its skies from Bolshevik invaders in 1919 and 1920. Inspired by the example of Tadeusz KoÊciuszko, who had fought for American independence, the American volunteers named their unit after the Polish and American hero. The logo shows thirteen stars and stripes for the original Thirteen Colonies, over which is KoÊciuszko’s four-cornered cap and two crossed scythes, symbolizing the peasant volunteers who, led by KoÊciuszko, fought for Polish freedom in 1794. After the Polish-Bolshevik war ended with Poland’s victory, the symbol was adopted by the Polish 111th KoÊciuszko Squadron. In September 1939, this squadron was among the first to defend Warsaw against Nazi bombers. Following the Polish defeat, the squadron was reformed in Britain in 1940 as Royal Air Force’s 303rd KoÊciuszko. This Polish unit became the highest scoring RAF squadron in the Battle of Britain, often defending London itself from Nazi raiders. The 303rd bore this logo throughout the war, becoming one of the most famous and successful squadrons in the Second World War. The title of our bulletin, Nihil Novi, invokes Poland’s ancient constitution of 1505. It declared that there would be “nothing new about us without our consent.” In essence, it drew on the popular sentiment that its American version expressed as “no taxation without representation.” The Nihil Novi constitution guar- anteed that “nothing new” would be enacted in the country without the consent of the Parliament (Sejm). -

Dariusz Libionka Reply to Review by Tomasz Domański Correcting The

Dariusz Libionka Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences / Polish Center for Holocaust Research orcid.org/0000-0003-0180-6463 [email protected] Reply to review by Tomasz Domański Correcting the Picture? Some Reflections on the Use of Sources in Night without End: The Fate of Jews in Selected Counties of Occupied Poland, volumes 1-2(Korekta obrazu? Refleksje źródłoznawcze wokół książki „Dalej jest noc. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski”) vol. 1- 2, eds Barbara Engelking, Jan Grabowski, Warsaw 2018 (Polish-Jewish Studies, Institute of National Remembrance , Warsaw 2019) Before I move on to the charges formulated by Dr. Tomasz Domański in his review, I need to briefly characterize what I wrote in my text published in Dalej jest noc. (Night without End). My text is 196 pages long. It deals with the extermination of the Jews in Miechów county (Kreis Miechów), part of the Cracow District and one of the largest counties in the General Government. The sheer scale shows that the research required substantial effort. The introduction contains a discussion of the literature, a characterization of Jewish settlements in the area, including Polish-Jewish relations, as well as the general situation in the inter-war period. The part that deals with the occupation beings by characterizing the local German administration and police forces, followed by a description of the situation of the Jews, with particular emphasis on the occupier’s policy toward the Jewish population, its size in the individual centers, the deportations within and outside of the county, the attempts to create ghettos, and of forced labor. -

Architektura Drewniana Wooden Architecture Małgorzata Skowrońska

Architektura drewniana Wooden architecture Małgorzata Skowrońska Architektura drewnianaWooden architecture Gminy Czarny Dunajec | The Commune of Czarny Dunajec Wydawnictwo Artcards Artcards Publishing House Czarny Dunajec | Chochołów 2014 4 Drewno z uczuciem 5 Drewno Drewno z uczuciem z uczuciem Wood with Wood with affection affection Drewno nie jest bezduszne. Domy z drewna mają niezaprzeczalny klimat. Są bliskie naturze, ekologiczne i zdrowe dla mieszkańców. Zanim zalaliśmy świat betonem, to właśnie drewno było budulcem, z którego powstawały domy. Te z płazów przeżywają swój renesans. Buduje się z nich nie tylko jednorodzinne budynki, ale też pensjonaty i restauracje. Stąd ta popularność? Kontakt z surowym drewnem i ciepło wnętrza domu stworzonego w tej technologii nie ma sobie równych. Zainteresowanie taką architekturą, podsycane dodatkowo modą na góralszczyznę, powoduje, że niemal w każdym zakątku Polski można znaleźć chatę stylizowaną na góralską nutę. Inną sprawą jest ocena tego rodzaju przeniesień w oderwanym od Podhala kontekście kulturowym i krajobrazowym. Takim, co tu dużo mówić, nie zawsze udanym eksperymentom, sprzyja technologia (łatwość demontażu i ponownego złożenia domu). To dlatego chaty góralskie można spotkać także w Niemczech, Francji czy USA. Wracając do źródeł architektury drewnianej nie można pominąć gminy Czarny Dunajec. Górska, klimatyczna i widokowa. To tylko kilka z określeń, na jakie zasługuje ziemia czarnodujanecka. Atmosferę podkręca położenie na pograniczu dwóch krain historyczno-etnograficznych – Orawy (na -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Szymon Datner German Nazi Crimes Against Jews Who

JEWISH HISTORICAL INSTITUTE BULLETIN NO. 75 (1970) SZYMON DATNER GERMAN NAZI CRIMES AGAINST JEWS WHO ESCAPED FROM THE GHETTOES “LEGAL” THREATS AND ORDINANCES REGARDING JEWS AND THE POLES WHO HELPED THEM Among other things, the “final solution of the Jewish question” required that Jews be prohibited from leaving the ghettoes they were living in—which typically were fenced off and under guard. The occupation authorities issued inhumane ordinances to that effect. In his ordinance of October 15, 1941, Hans Frank imposed draconian penalties on Jews who escaped from the ghettoes and on Poles who would help them escape or give them shelter: “§ 4b (1) Jews who leave their designated quarter without authorisation shall be punished by death. The same penalty shall apply to persons who knowingly shelter such Jews. (2) Those who instigate and aid and abet shall be punished with the same penalty as the perpetrator; acts attempted shall be punished as acts committed. A penalty of severe prison sentence or prison sentence may be imposed for minor offences. (3) Sentences shall be passed by special courts.” 1 In the reality of the General Government (GG), § 4b (3) was never applied to runaway Jews. They would be killed on capture or escorted to the nearest police, gendarmerie, Gestapo or Kripo station and, after being identified as Jews and tortured to give away those who helped or sheltered them, summarily executed. Many times the same fate befell Poles, too, particularly those living in remote settlements and woodlands. The cases of Poles who helped Jews, which were examined by special courts, raised doubts even among the judges of this infamous institution because the only penalty stipulated by law (death) was so draconian.