Path-Breaking.” —Jim Collins —Clayton M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blowout Resistant Tire Study for Commercial Highway Vehicles

Final Technical Report for Task Order No. 4 (DTRS57-97-C-00051) Blowout Resistant Tire Study for Commercial Highway Vehicles Z. Bareket D. F. Blower C. MacAdam The University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute August 31,2000 Technical Report Documen~tationPage Table of Contents 1. Overview ..................... ..........................................................................................1 2 . Crash Data Analysis of Truck Tire Blowouts ........................................ 3 Truck tire blowouts in FARS (Fatality Analysis Reporting System) and TIFA (Trucks Involved in Fatal Accidents) ........................................................................................3 Truck tire blowouts in GES .........................................................................................8 Fatalities and injuries in truck tire blowout crashes ..................................................10 State data analysis ....................................................................................................10 Crashes related to truck tire debris ...........................................................................12 3 . Information Review of Truck Tire Blowouts .........................................................15 Literature Review ................. .............................................................................15 Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations, Rules and Notices ...................................21 Patent Database Research ....................... .. .......................................................23 -

Service Bulletin 89-020

Service Bulletin 89-020 Applies To: ALL June 24, 2008 Required Special Tools and Equipment (Supersedes 89-020, dated March 1, 2007, to update the information marked with black bars) In accordance with the Automobile Sales and Service Agreement, Section 3.9, your service department is required to have, at a minimum, the tools and equipment listed in this bulletin. When a new model is introduced and requires special tools, those tools may be shipped to you automatically. If you receive a required special tool and believe you have an equivalent, refer to the Acura Dealer Operations Manual, Section 11, for the procedure to return items that have been distributed through the tool and equipment program. REQUIRED SERVICE MANUALS Dealers are required to have a copy of each Service Manual, Electrical Troubleshooting Manual, and Body Repair Manual listed on the Helm web site, www.helminc.com. REQUIRED SPECIAL TOOLS These tools are available from Acura. Use normal parts ordering procedures. Use the check (9) column to identify the tools you already have. NOTE: All tools are in single quantity units unless noted in italics under the Description heading. Axle/Differential Tools Tool 9 Tool Number Drawer Description Location 07947-4630100 9 Fork Seal Driver 07947-SB0A100 9 Driver 07AAD-S3VA000 9 Driveshaft Remover 07AAD-S9VA000 6 Driveshaft Remover 07AAD-SJAA100 6 Front Driveshaft-Intermediate Shaft Remover 07JAD-PL9A100 9 Driver 07NAD-P20A100 9 Driver, 52 x 55 mm 07NAF-SR3A101 9 Half Shaft Base 07XAC-001010A 6 Threaded Adapter, 22 x 1.5 mm 07XAC-001020A -

Annual Report 2005 Michelin Energy E3A the Benchmark for Low Rolling Resistance, the Michelin Energy E3A Range of Tires Delivers 3% Fuel Savings for Passenger Cars

Annual Report 2005 Michelin Energy E3A The benchmark for low rolling resistance, the Michelin Energy E3A range of tires delivers 3% fuel savings for passenger cars. The third generation of this tire family, Michelin Energy E3A also delivers a 10% improvement on grip and 20% more mileage than the previous range. 1895 For the Paris- Bordeaux-Paris race, 2005 Michelin built and Michelin and its partners won drove the Eclair, all the World Champion titles: the first car ever fitted • Formula 1 World Champion with pneumatic tires. • Rally World Champion • 24 Hours of Le Mans Champion • MotoGP World Champion • and MBT World Champion Because, in 2005 as in 1895, Michelin placed innovation at the heart of its development. Today’s world No.1 tire manufacturer with 19.4%* market share, Michelin is at the forefront of all tire markets and travel-related services thanks to the quality of its product offering. Michelin is undisputed leader in the most demanding technical segments and designs forward-looking solutions to help the road transportation industry in its bid to improve competitive edge and to meet modern societies’ ever more pressing needs for safety, fuel efficiency and respect for the environment. To further strengthen its position and performance, Michelin pursues a global, targeted growth strategy focusing on high value-added segments and on expansion in the higher-growth markets, while improving its productivity across the board. * Accounting for 19.4% of world tire sales according to Tire Business, August 29, 2005. In a nutshell, its mission is to promote its values of Respect for Customers, People, Shareholders, the Environment and Facts in contributing to mobility enhancement of both goods and people. -

Enterprise – Automotive Industry

FINAL REPORT SSUURRVVEEYY OONN MMOOTTOORR VVEEHHIICCLLEE TTYYRREESS && RREELLAATTEEDD AASSPPEECCTTSS (ENTR/02/045) prepared by: commissioned by: The European Commission Enterprise Directorate General Unit ENTR/F/5 TÜV Automotive is accredited under DAR-registration number KBA • P 00001-95 to the accreditation body of the Kraftfahrt-Bundesamt, Federal Republic of Germany. Final Report “Motor Vehicle Tyres And Related Aspects” Commissioned by: The European Commission Enterprise Directorate General Prepared by: TÜV Automotive GmbH Authors: Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Walter Reithmaier Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Thomas Salzinger PRELIMINARY REMARK: The investigations within the scope of this survey and the composition of the present report were carried out in all conscience and to the best of our knowledge. As can be seen in the list of references, some sources refer to pages on the Internet. As this medium is subject to fast changes, some references may no longer be found at the addresses given in the list. The list of references represents the state at delivery of the first draft version of this report. ______________________________________________________________ SURVEY ON MOTOR VEHICLE TYRES AND RELATED ASPECTS – 2003 - Page 2 CONTENTS: A: GENERAL PART 0 GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS................................................................................ 9 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................... 11 1.1 BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE............................................................................ -

Driving with a Flat Tire

05/08/16 21:18:06 31SJA610 0397 Driving With a Flat Tire Michelin PAX System If equipped Your vehicle is equipped with the Michelin PAX system. Since each Michelin PAX system tire has an inner support ring that allows it to continue running without air, it may be difficult to immediately judge from its appearance if a tire is punctured. Your vehicle is also equipped with a tire pressure monitoring system (TPMS), and this system may be your first detection of a flat tire. The TPMS monitors the air pressure it was probably a natural loss of the of all four tires whenever the ignition air pressure and you can continue switch is in the ON (II) position. It driving as before. will immediately sense if a tire starts to lose its pressure, and give you If the indicator and the message warning with the low tire pressure come on again, you probably have a indicator in the instrument panel and flat tire. In this case, you will see a a ‘‘CHECK TIRE PRESSURE’’ ‘‘PAX SYSTEM WARNING’’ message on the multi-information message on the multi-information display. If the indicator and the display. warning message do not come on again after you inflate the tire to its correct air pressure (see page384 ), 394 05/08/16 21:18:12 31SJA610 0398 Driving With a Flat Tire With the PAX system tires, you can drive up to about 125 miles (200 km) even if one or more of your tires are punctured. This allows you to drive to the nearest Acura dealer or authorized Michelin PAX system dealer to have the tire(s) repaired. -

Benefit Terms and Conditions

Benefit Terms and Conditions GradGuard™ is a service of Next Generation Insurance Group, LLC. NGI STUDENT COMBINED Kindred T ravel WORDING International MEMBERSHIP PLAN FOR RETURN OF MORTAL REMAINS AND / Travel expense will be based on the cost of Economy Transportation OR EMERGENCY TRAVEL ASSISTANCE and subject to the Maximum Single Limit Amount. Expenses that exceed This document describes all of the travel and repatriation benefits the Maximum Coverage Amount or that are not arranged through the issued by Kindred Travel LLC, (The Company) under this Membership. contracted Travel Assistance Service provider are the responsibility of the Covered Person and no benefits will be payable. Benefits are not Please refer to the accompanying Summary of Coverage. It provides payable for hospital stays less than 5 days. This 5 day hospital limitation specific information about the plan. The Family Member should does not apply if the Family Member passes away. Emergency contact the Company immediately if he or she believes that the Transportation Services will not be payable for a Sickness, as defined Summary of Coverage is incorrect. herein that occurs within the Waiting Period, as defined herein. TABLE OF CONTENTS: 2. Return of Mortal Remains: (Applicable to students only) I. ELIGIBILITY In the event of a Covered Person’s death which occurs more than 150 miles II. COVERAGES away from the Covered Person’s Home, benefits will be payable for III. DEFINITIONS services arranged through the contracted Travel Assistance Service IV. PROVISIONS Provider for the return of the Covered Persons mortal remains. Services include arranging for the following: locating a sending funeral home; V. -

2000 ANNUAL REPORT Cle Can Be Caused by Hitting a Curb Or Pothole

THE GOODYEAR TIRE & RUBBER COMPANY THE GOODYEAR Pressure — It is important to have the proper air pressure in your tires, as underinflation is the leading cause of tire failure. It results in tire stress and irregular wear. The correct amount of air for your tires is specified by the vehicle manufacturer and shown on the vehicle door edge, door post, glove box door or fuel door. It is also listed in the owner’s manual. Check your tires’ air pressure at least once a month. This should be done when your tires have not been driven a distance and are still cold. Alignment — Misalignment of wheels on the front or rear of your vehi- 2000 ANNUAL REPORT 2000 ANNUAL cle can be caused by hitting a curb or pothole. It can result in uneven and rapid treadwear. Have your vehicle’s alignment checked periodically as specified in the owner’s manual or whenever you have an indication of trouble such as pulling or vibration. Also, have your tire balance checked periodically. An unbalanced tire and wheel assembly may result in irregular wear. Rotation — Sometimes irregular tire wear can be corrected by rotating your tires. Consult your vehicle’s owner’s manual, the tire manufacturer or your tire retailer for the appropriate rotation pattern for your vehicle. If your tires show uneven wear, ask your tire retailer to check for and correct any misalignment, imbalance or other mechanical problem involved before rotation. Tires should be rotated at least every 6,000 miles. Tread — Tires must be replaced when the tread is worn down to one- sixteenth of an inch in order to prevent skidding and hydroplaning. -

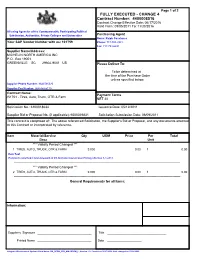

CHANGE 4 Contract Number: 4400008516

Page 1 of 2 FULLY EXECUTED - CHANGE 4 Contract Number: 4400008516 Contract Change Effective Date: 06/17/2016 Valid From: 09/05/2011 To: 11/30/2016 All using Agencies of the Commonwealth, Participating Political Subdivision, Authorities, Private Colleges and Universities Purchasing Agent Name: Ralph Constance Your SAP Vendor Number with us: 101759 Phone: 717-703-2931 Fax: 717-783-6241 Supplier Name/Address: MICHELIN NORTH AMERICA INC P.O. Box 19001 GREENVILLE SC 29602-9001 US Please Deliver To: To be determined at the time of the Purchase Order unless specified below. Supplier Phone Number: 8644586030 Supplier Fax Number: 864-458-5119 Contract Name: Payment Terms 251701 - Tires, Auto, Truck, OTR & Farm NET 30 Solicitation No.: 6100018634 Issuance Date: 05/12/2011 Supplier Bid or Proposal No. (if applicable): 6500039831 Solicitation Submission Date: 06/09/2011 This contract is comprised of: The above referenced Solicitation, the Supplier's Bid or Proposal, and any documents attached to this Contract or incorporated by reference. Item Material/Service Qty UOM Price Per Total Desc Unit *** Validity Period Changed *** 1 TIRES, AUTO, TRUCK, OTR & FARM 0.000 0.00 1 0.00 Item Text Reference attached Commonwealth of PA Michelin Government Pricing effective 3-1-2011. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- *** Validity Period Changed *** 2 TIRES, AUTO, TRUCK, OTR & FARM 0.000 0.00 1 0.00 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

United States District Court for New Mexico Adopted the Same Analysis

FILED 1st JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT Santa Fe County STATE OF NEW MEXICO 8/28/2019 5:03 PM COUNTY OF SANTA FE STEPHEN T. PACHECO CLERK OF THE COURT FIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT Leticia Cunningham LINDA HOLLINGER LAMAR, D. MARIA SCHMIDT, as Personal Representative of the Estate of TERRY MASON, Deceased, TAMICA BRUMFIELD, LEE GAINES, and SUSIE GAINES, Plaintiffs, v. No. D-101-CV-2019-00098 BRIDGESTONE AMERICAS TIRE OPERATIONS, LLC, a foreign company which is the successor to BRIDGESTONE/ FIRESTONE NORTH AMERICAN TIRE, LLC; JAG TRANSPORTATION, INC.; ELISARA TAITO; GREYHOUND LINES, INC.; LUIS FELIPE ALVAREZ; and THE NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, Defendants. RESPONSE OPPOSING DEFENDANT BRIDGESTONE AMERICAS TIRE OPS., LLC'S MOTION TO DISMISS FOR LACK OF PERSONAL JURISDICTION COME NOW Plaintiffs, LINDA HOLLINGER LAMAR, D. MARIA SCHMIDT, as Personal Representative of the Estate of TERRY MASON, Deceased, and TAMICA BRUMFIELD, by and through their attorneys, The Ammons Law Firm, L.L.P. (Robert E. Ammons, Esq., John Gsanger, Esq., and April A. Strahan, Esq.) and Durham, Pittard & Spalding, L.L.P. (Justin R. Kaufman, Esq., Rosalind B. Bienvenu, Esq., and F. Leighton Durham, Esq.), and respond in opposition to the Motions to Dismiss for Lack of Personal Jurisdiction filed by Defendant Bridgestone Americas Tire Ops., LLC (“Bridgestone”), and request that this motion be denied: I. Background of the Episode-in-Suit1 This case involves a multiple-fatality truck and bus crash on I-40 in McKinley County, New Mexico, caused by the catastrophic failure of a Bridgestone FS591 truck tire mounted on the left side of the steer axle on a Jag Transportation truck. -

An Assessment of Mass Reduction Opportunities for a 2017-2020

An Assessment of Mass Reduction Opportunities for a 2017 – 2020 Model Year Vehicle Program Prepared by: Lotus Engineering Inc. Submitted to: The International Council on Clean Transportation March 2010 Rev 006A Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................6 2. NOMENCLATURE...............................................................................................................................9 3. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................20 4. WORKSCOPE .....................................................................................................................................22 4.1. Methodology .............................................................................................................22 5. BODY STRUCTURE ..........................................................................................................................26 5.1. Overview...................................................................................................................26 5.2. Trends.......................................................................................................................26 5.3. Benchmarking...........................................................................................................30 5.4. Analysis.....................................................................................................................31 -

Vysoké Učení Technické V Brně, Ústav Soudního Inženýrství, 2016

VYSOKÉ UČENÍ TECHNICKÉ V BRNĚ BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY ÚSTAV SOUDNÍHO INŽENÝRSTVÍ INSTITUTE OF FORENSIC ENGINEERING ÚSTAV SOUDNÍHO INŽENÝRSTVÍ INSTITUTE OF FORENSIC ENGINEERING VLIV HLOUBKY DEZÉNOVÉ DRÁŽKY NA DOSAŽITELNÉ ZPOMALENÍ VOZIDLA INFLUENCE OF TREAD GROOVES DEPTH ON ACHIEVABLE VEHICLE DECELERATION DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE MASTER'S THESIS AUTOR PRÁCE Bc. Barbora Kejíková AUTHOR VEDOUCÍ PRÁCE Ing. Albert Bradáč, Ph.D. SUPERVISOR BRNO 2016 Abstrakt Práce je věnována pneumatikám osobních automobilů. Teoretická část zahrnuje popis výroby, konstrukce a parametrů pneumatik. Praktická část je tvořena experimentálním měřením, jehož cílem je zjistit vliv hloubky dezénu na brzdné zpomalení vozidla. Nejprve se zaměřuje na přípravu podmínek měření, s následným zpracováním a vyhodnocením získaných dat. Abstract This thesis is devoted on passenger car tyres. Theoretical part covers description of production, construction and tyre parameters. Practical part is comprised experimental measurement of influence of tread grooves depth on achievable vehicle deceleration. First, it is focused on preparation conditions of measurement, with subsequent processing and evaluation of the data obtained. Klíčová slova Pneumatika, gumárenská směs, hloubka dezénu, brzdná dráha, brzdné zpomalení. Keywords Tyre, rubber compounds, tread grooves depth, breaking distance, braking deceleration. Bibliografická citace KEJÍKOVÁ, B. Vliv hloubky dezénové drážky na dosažitelné zpomalení vozidla. Brno: Vysoké učení technické v Brně, Ústav soudního inženýrství, 2016. 60 s. Vedoucí diplomové práce Ing. Albert Bradáč, Ph.D. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci zpracovala samostatně a že jsem uvedla všechny použité informační zdroje. V Brně dne 27.5.2016 ………………………………………. podpis diplomanta Poděkování Chtěla bych poděkovat panu Ing. Albertu Bradáčovi, Ph.D. za odborné vedení této diplomové práce a za pomoc i věcné rady při jejím zpracování. -

ATASA 5 Th Tires, Wheels, & Wheel Bearings

ATASA 5 th Tires, Wheels, & Wheel Bearings Systems Repair Worksheet Please Read The Summary Chapter 44 Pages: 1297 1332 Tires, Wheels, and Bearings Danger of Old Tires!! 74 Points Before We Begin… Keeping in mind the Career Cluster of Transportation , Distribution & Logistics Ask yourself: What careers might be present in this slide series? What careers might interest me? How do these careers relate to my other high school classes? What career cluster is my 4year plan preparing me for? ATASA 5 th Tires, Wheels, & Wheel Bearings 1. Uneven or premature tire wear is a good indicator of ________________ & ______________ problems. Steering & Suspension Ignition & Fuel Brake & Suspension ATASA 5 th Tires, Wheels, & Wheel Bearings ATASA 5 th Tires, Wheels, & Wheel Bearings 2. Lightweight aluminum wheels reduce the amount of vehicle _____________ weight for better ride. Imagine a car of 2000 lbs with wheels of 200 lbs . Each time this car would hit a bump it would almost be launched!!.....but if the wheels were 20 lbs the car would barely notice the bump. This means that everything that goes up and down (i.e. the wheel and most part of the suspension) should be kept as light as possible to provide a comfortable ride. Also in the figure can be noticed that the time which the wheel loses contact with the road increases with the weight of the wheel and suspension. This can be reduced by stiffening the springs of the suspension but then.....this will not do any good to a smooth ride. The weight which goes up and down when a car hits a bump is called the unsprung weight....the car body itself the sprung weight.