THE FLORIDA PROJECT By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Epcot Cheat Sheet

Mitsukoshi Store and Via The Culture Tutto Napoli Gusto American Exhibit Liberty Adventure Inn Katsura Teppan Edo Tutto Grill Italia Sommerfest Tokyo Dining Restaurant Marrakesh Bier- garten Gardens Tangierine Cafe Theater France Boulangerie Pâtisserie Japan Spice Road Ice Cream Refreshment Italy Table Coolpost Germany American Impressions Pavilion Morocco Chefs de France de France Boat/Walkway to France Bistro Hollywood Studios, BoardWalk de Paris and Epcot Resorts International China IllumiNations Gateway Lotus Blossom Yorkshire County of China + FP+ Nine Dragons Fish Shop United Kingdom Norway Akershus Rose & Crown Pub & Dining Room Kringla Bakeri Maelstrom La Hacienda + de San Angel Mexico Canada Cantina World Showplace de San Angel San Angel Mexico Inn Shops and Showcase La Cava Le Cellier del Plaza Tequila O’ Canada! Gran Fiesta Tour Odyssey Captain Center EO++ Journey Into Imagination With Figment+ Test Soarin’+ Track+ Club Mouse Cool Sunshine Gear Character Seasons FP+ Fountain Spot + Garden Mission: Grill Sum of FP+ (Top Floor) Space Electric FP+ + All Thrills Umbrella FP+ Sunshine Innoventions Seasons East Innoventions Circle of Life Living with West (Top Floor) the Land+ FP+ Festival Center Spaceship Ellen’s Energy Turtle Earth Nemo Talk Adventure Guest + + Ride+ Services Coral Reef First Hour Attractions Living Seas Attraction Entrance First 2 Hours / Last 2 Hours of Operation Restrooms Anytime Attractions Main Entrance Table Service Dining and Exit Guest Services Quick Service Dining Resort Shopping Bus Stops IllumiNations Viewing Attractions followed by a + are FastPass+ enabled Epcot Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Epcot has two entrances. At the main entrance, a brief welcome spiel will play over the speakers beginning at 8:45am. -

C a Ta Logue 20 20

CATALOGUE 2020 1 Flame Media is an internationally focused media organisation offering a suite of fully integrated services to content producers and buyers across all platforms. Contents Our business includes our UK-based production arm Wildflame and our new German production officeFlame Media GmbH; In Development 1 a footage clipping service; channel sales; a multifunctional, In Production 6 sound-controlled studio facility in Sydney and a project finance, mergers and acquisitions advisory service. Lifestyle & Reality 9 Crime & Justice 22 Alongside these offerings isFlame Distribution, an international content distribution business with offices in London, Health & Medical 26 Sydney, Singapore, North America, Greece and The Philippines, Science & Technology 30 and representation in Latin and North America. Flame Distribution represents over 3,000 hours of content from more than 180 Nature & Wildlife 35 independent producers from around the world. We work to slow TV 42 maximise the audience and financial returns on completed Biography 44 content, assist our producers find co-production opportunities, seek presales and advise on project financing. Documentary 52 The Flame sales team works with buyers across all platforms to History 63 offer a wide range of high-end factual and documentary content. Food 76 Our aim is to deal in a proactive, flexible and professional manner at all times. Travel & Adventure 87 Kids 95 Our team, across the entire Flame Media business, is always available to speak to you about your production or content needs. Sport 98 Best wishes, Arts 101 Formats 104 Adelphi Films 107 John Caldon Index 110 Managing Director 2 In Development IN DEVELOPMENT IN NEW Decisive Moment: 9/11 1 x 60 min, HD The documentary, made in partnership with Magnum Photos in anticipation of the 20th anniversary in 2021 of the September 11 terror attacks, is a thoughtful, intelligent and emotional reflection of the tragic events as seen through the work and memories of the photographers who were in Manhattan that day. -

ADHD in the Shadows

Complex, Comorbid, Contraindicated, and Confusing Patients Bill Dodson, M.D. Private Practice [email protected] Roberto Olivardia, Ph.D. Harvard Medical School [email protected] ADHD in the Shadows • Importance of comorbid disorders • ADHD often not even assessed at intake • ADHD vastly underdiagnosed, especially in adults • Even when ADHD is known it is clinically underappreciated Why did we think that ADHD went away in adolescence? • True hyperactivity was either never present or diminishes to mere restlessness after puberty. • People learn compensations (but is this remission?). • People with ADHD stop trying to do things in which they know they will fail. • People with ADHD drop out of society or end up in jail and are no longer available for studies. • “Helicopter Moms” compensate for their ADHD children, adolescents, and adults. Recognition and Diagnosis • Most clinicians who treat adults never consider the possibility of ADHD. • Less than 8% of psychiatrists and less than 3% of physicians who treat adults have any training in ADHD. Most report that they do not feel confident with either the diagnosis or treatment. (Eli Lilly Marketing Research) • ADHD in adults is an “orphan diagnosis” ignored by the APA, the DSM, and training programs 38 years after it was officially recognized to persist lifelong. It is Not Adequate to Merely Extend Childhood Criteria • Some symptoms diminish with age (e.g., hyperactivity becomes restlessness). • Some new symptoms emerge (sleep disturbances, reactive mood lability). • Life demands get harder. Adults with ADHD must do things that a child doesn’t…Love, Work, and raise kids (half of whom will have ADHD). -

Siemens Technology at the New Seven Dwarfs Mine Train

Siemens Technology at the new Seven Dwarfs Mine Train Lake Buena Vista, FL – Since 1937, Snow White and Seven Dwarfs have been entertaining audiences of all ages. As of May 28, 2014, the story found a new home within the largest expansion at the Magic Kingdom® Park. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, along with a host of new attractions, shows and restaurants now call New Fantasyland home. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, an exciting family coaster, features a forty-foot drop and a series of curves that send guests seated in mine cars swinging and swaying through the hills and caves of the enchanted forest. As part of the systems used to manage the operation of this new attraction, Walt Disney Imagineering chose Siemens to help automate many of the attraction‟s applications. Thanks to Siemens innovations, Sleepy, Doc, Grumpy, Bashful, Sneezy, Happy and Dopey entertain the guests while Siemens technologies are hard at work throughout the infrastructure of the attraction. This includes a host of Siemens‟ systems to ensure that the attraction runs safely and smoothly so that the mine cars are always a required distance from each other. Siemens equipment also delivers real-time information to the Cast Members operating the attraction for enhanced safety, efficiency and communication. The same Safety Controllers, SINAMICS safety variable frequency drives and Scalance Ethernet switches are also found throughout other areas of the new Fantasyland such as the new Dumbo the Flying Elephant®, and Under the Sea – Journey of the Little Mermaid attractions. And Siemens Fire and Safety technologies are found throughout Cinderella Castle. -

Promoting Optimum Mental Health Through Counseling: an Overview

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 425 384 CG 028 942 AUTHOR Hinkle, J. Scott, Ed. TITLE Promoting Optimum Mental Health through Counseling: An Overview. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Student Services, Greensboro, NC. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-1-56109-084-0 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 339p. CONTRACT RR93002004 AVAILABLE FROM CAPS Publications, Inc., P.O. Box 26171, Greensboro, NC 27402-6171. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020)-- Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Clinical Diagnosis; Counseling; *Counseling Techniques; *Mental Health; Prevention; *Psychology IDENTIFIERS *Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ABSTRACT A broad selection of topics representing important aspects of mental health counseling are presented in 56 brief articles. Part 1, "Overview: The Evolution of Mental Health Counseling," provides definition and a discussion of training and certification. Other chapters address the history, development, and future of the field, freedom of choice issues, and prevention. Part 2,"Client Focus in Mental Health Counseling," offers articles on mandated clients, sexual harassment in the workplace, homophobia, male couples, infertility, prevention with at-risk students, children in the aftermath of disaster, family therapy for anorexics, Dialectical Behavior Therapy counseling, stress, adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse, mediation with victims and offenders, developmental counseling for men, teenage parents, and student athletes. Part 3,"Multiculturalism in Mental Health Counseling," addresses the importance of a multicultural perspective, multicultural counseling in mental health settings, and the competency and preparation of counselors. Part 4, "Special Emphases in Mental Health Counseling," discusses topics including pastors as advocates, religious issues, death and loss education, wellness, outdoor adventure activities, managed care, and consultation. -

Zpuer Aeternus | Mythology | Carl Jung

Puer aeternus From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Puer aeternus is Latin for eternal boy , used in mythology to designate a child-god who is forever young; psychologically, it is an older man whose emotional life has remained at an adolescent level. The puer typically leads a provisional life, due to the fear of being caught in a situation from which it might not be possible to escape. e covets independence and freedom, chafes at boundaries and limits, and tends to find any restriction intolerable. !"# Contents !hide# • " The puer in mythology • $ The puer in %ungian psychology o $." Writings • & 'eter 'an syndrome • ( )otable modern-day 'eter 'an • * +ee also • )otes • Further reading • /0ternal links The puer in mythology !edit# The words, puer aeternus, come from Metamorphoses, an epic work by the 1oman poet 2vid 3(& 45 6 c." 789 dealing with :reek and 1oman myths. n the poem, 2vid addresses the child-god acchus as puer aeternus and praises him for his role in the /leusinian mysteries. acchus is later identified with the gods 8ionysus and /ros. The puer is a god of vegetation and resurrection, the god of divine youth, such as Tammu<, 7ttis and 7donis.!$# The figure of a young god who is slain and resurrected also appears in /gyptian mythology as the story of 2siris. The puer in Jungian psychology !edit# +wiss psychiatrist 5arl :ustav %ung developed a school of thought called analytical psychology, distinguishing it from the psychoanalysis of +igmund Freud 3"*6"=&=9. n analytical psychology 3often called >%ungian psychology>9 the puer aeternus is an e0ample of what %ung called an archetype, one of the >primordial, structural elements of the human psyche>.!&# The shadow of the puer is the senex 3Latin for >old man>9, associated with the god 5ronus? disciplined, controlled, responsible, rational, ordered. -

With Flights!

WIN AN EPIC ADVENTURE FOR FOUR TO PERU – WITH FLIGHTS! Who will you bring? Who among your friends and family will accept the challenge of changing the world simply by having the time of their life? gadventures.com.au Terms and conditions apply. Visit website for more details. LoveAwaits Wednesday 2nd November 2016 Win a trip to Peru! Crystal Yacht rebrand G ADVENTURES is offering the itravel affiliate program LUXURY cruise and hospitality travel trade a chance to win a EXCLUSIVE gives agents, whether retail or brand Crystal has announced it’s trip for four people to Peru for its THE evolution of Sydney-based mobile, the ability to work and changing the identity of its Crystal eight-day Inca Discovery as part retail travel firm itravel continues, use our buying power.” Yacht Cruises brand to Crystal of a new competition. with the company launching a Labroski said Link provided a Yacht Expedition Cruises. The “epic adventure of a brand new affiliate program to “generous offering”, with 1-year The rebrand capitalises on the lifetime” includes flights from lure potential new members. contracts for agency flexibility. recent completion of Crystal Australia to Peru and is valued at Dubbed ‘Link’ (and carrying “We are really trying to make Serenity’s Northwest Passage more than $43,700. the familiar green it as easy as possible for voyage and extensive research by Entry requires no purchase or dotted ‘i’), the initiative people to look at what else the line which found about 70% payment - see the cover wrap. undertaken by itravel is out there in the market. -

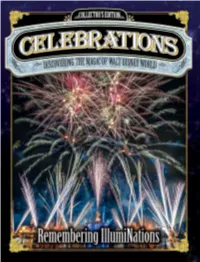

Herein Are Those of the Authors and Advertisers and Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of the Publisher

Editor Tim Foster Contributing Writers Lindsay Mott Lori Elias Jamie Hecker Associate Editors Lisa Mahan • Michelle Foster Creative Direction and Design Tim Foster Associate Art Director Michelle Foster Contributing Photographers Tim Devine Garry Rollins Tim Foster ISBN-13: 978-1-5323-2121-4 ©2018 Celebrations Press, Inc. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. Statements and opinions herein are those of the authors and advertisers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. Celebrations is owned and operated by Celebrations Press, Inc. and is not affiliated with, authorized or endorsed by, or in any way officially connected with the Walt Disney Company, Disney Enterprises, Inc., or any of their affiliates. Walt Disney World Resort® is a registered trademark of The Walt Disney Company. This publication makes reference to various Disney copyrighted characters, trademarks, marks, and registered marks owned by The Walt Disney Company, Disney Enterprises, Inc., and other trademark owners. The use in this book of trademarked names and images is strictly for editorial purposes, no commercial claim to their use, or suggestion of sponsorship or endorsement, is made by the authors or publishers. Those words or terms that the authors have reason to believe are trademarks are designated as such by the use of initial capitalization, where appropriate. However, no attempt has been made to identify or designate all words or terms to which trademark or other proprietary rights may exist. Nothing contained herein is intended to express a judgement on, or affect the validity of legal status of, any word or term as a trademark, service mark, or other proprietary mark. -

Convergence Culture: an Approach to Peter Pan, by JM Barrie Through

Departamento de Filoloxía Inglesa e Alemá FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA Convergence Culture: An approach to Peter Pan, by J. M. Barrie through “the fandom”. SHEILA MARÍA MAYO MANEIRO TRABALLO FIN DE GRAO GRAO EN LINGUA E LITERATURA INGLESAS LIÑA TEMÁTICA: Texto, Imaxe e Cibertexto FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA CURSO 2017/ 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. GENERIC FEATURES ............................................................................................................. 5 2.1. Convergence Culture ................................................................................................................. 5 2.2. Importance of the fans as ‘prosumers’ ................................................................................. 8 3. PETER PAN AS A TRANSMEDIAL FIGURE .......................................................... 15 4. PETER PAN AS A FANFICTION ..................................................................................... 19 4.1. Every Pain has a Story .............................................................................................................. 19 4.2. The Missing Thimble ................................................................................................................ 24 4.3. Duels ............................................................................................................................................... -

Holiday Planning Guide

Holiday Planning Guide For more information, visit DisneyParks.com.au Visit your travel agent to book your magical Disney holiday. The information in this brochure is for general reference only. The information is correct as of June 2018, but is subject to change without prior notice. ©Disney © & TM Lucasfilm Ltd. ©Disney•Pixar ©Disney. 2 | Visit DisneyParks.com.au to learn more, or contact your travel agent to book. heme T Park: Shanghai Disneyland Disney Resort Hotels: Park Toy Story Hotel andShanghai Disneyland Hotel ocation: L Pudong District, Shanghai Theme Parks: Disneyland Park and hemeT Parks: DisneyCaliforniaAdventurePark Epcot Magic ,Disney’s Disney Resort Hotels: Disneyland Hotel, Kingdom and Disney’s Hollywood Pa Pg 20 Disney’sGrandCalifornianHotel & Spa rk, Water Parks: Animal Studios and Disney’sParadisePier Hotel Kingdom Water Park, Disney’s Location: Anaheim, California USA B Water Park Disney’s lizzard T Beach isneyD Resort Hotels: yphoon Lagoon Pg 2 ocation:L Orlando, Florida25+ USA On-site Hotels Pg 6 Theme Parks: Disneyland® Park and WaltDisneyStudios® Park amilyF Resort unty’sA Beach House Kids Club Disney Resort Hotels: 6 onsite hotels aikoloheW Valley Water playground and a camp site hemeT Park: Location: Marne-la-Vallée, Paris, France aniwai,L A Disney Spa and Disney Resort Hotels:Hong Kong Painted Sky Teen Spa Disney Explorers Lodge andDisneyland Disney’s Disneyland ocation: L Ko Olina, Hawai‘i Pg 18 Hollywood Hotel Park isneyD Magic, ocation:L Hotel, Disney Disney Wonder, Dream Lantau Island, Hong Kong and Pg 12 Character experiences,Disney Live Shows, Fantasy Entertainment and Dining ©Disney ocation: L Select sailing around Alaska and Europe. -

Star War Celebration

Pierce County Library System celebrates the outstanding contributions of teenage 2007 writers in the Library System’s 11th annual Teen Poetry and Fiction Writing winners Contest—Our Own Words. This year, 750 Final Judges: 7th-12th grade students competed in the Janet Wong poetry and short story writing contest. Brent Hartinger Nearly 50 volunteers including Library staff and Pierce County Library Foundation Board members reviewed the entries. Noted young adult author Brent Hartinger and poet Janet Wong chose this year’s winners in three grade groupings (7th and 8th grade, 9th and 10th grade, and 11th and 12th grade). The judges reviewed the pieces for originality, style, general presentation, grammar, and spelling. Pierce County Library Foundation awarded the winners with cash prizes and the winning entries are published in this book. Pierce County Library System gratefully acknowledged the support of the Pierce County Library Foundation, The News Tribune, Pierce County Arts Commission, and other community partners for continued support of the teen writing contest. Poetry Winners Grades 7 & 8 1st My Favorite Place by Adria Olson 7th Edgemont JHS 2nd Bloody Sunday by Chergai Castanza 7th Kopachuck MS 3rd My Green Cheetos Grandpa by Marena Struttmann 8th Gault MS Grades 9 & 10 1st Peter Pan Syndrome by Kenna Clough 10th Mt. Rainier Lutheran HS 2nd Doll Man by Kayley Rae 10th Spanaway Lake HS 3rd The End of Regret by Tim Owen 10th Homeschool Grades 11 & 12 1st Cadenza by Katie Bunge 12th Stadium HS 2nd Malhumoured by Stephanie Dering 12th -

643-2711 MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD I

28 - EVENING HERALb, Wed., Jan. 14, 1981 VOL. C, No. 89 — Manchester, Conn., Thursday, January 16, 1981 I jhave found a method of making money Go ahead. Take your time. Go over my Deep freeze that is no less than FANTASTIC. Up until material at home for thirty one (31) days Frost kill With l^ew England in the deep freeze, this now, I have only shared this idea with my residents might have to be evacuated as ships A farm worker in Homestead, Fla., zalone, owner of this plot and another 30 after I send it to you. That will give you is Nantucket Harbor frozen over with ice in family and close friends. They are all p d barges are unable to crack through the salvages zucchini as the sun rises over 30 acres of yellow squash, says he lost about 50 plenty of time to get the material and look it spots over four-feet thick. Due to the freeze, ice. Here Craig Soctt, 25, empties scallop acres of wilted plants Wednesday, a day after supplies and fuel are critically low and percent of his crops, worth close to $100,000. CASHING IN!!! over without risking a dime. dredges from his icebound Dory. (UPI photo) freezing temperatures hit this vegetable far (UPI photo) ■ ' ming area southwest of Miami. Cesara Lin- If you do NOTHING more OR less than But, don't go and tell all your friends what Most people don't believe that! WHY? I tell you to do, the results will be hard to you are doing.