Interviews Referencing Calvin F. Schmid PAA President in 1965-66

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Joint Session With

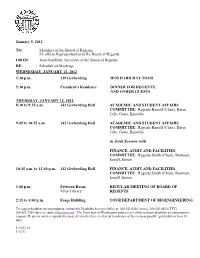

January 5, 2012 TO: Members of the Board of Regents Ex officio Representatives to the Board of Regents FROM: Joan Goldblatt, Secretary of the Board of Regents RE: Schedule of Meetings WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2012 3:30 p.m. 139 Gerberding HUB HARD HAT TOUR 5:30 p.m. President’s Residence DINNER FOR REGENTS, AND OTHER GUESTS THURSDAY, JANUARY 12, 2012 8:30 to 9:35 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles 9:45 to 10:35 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles in Joint Session with FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Brotman, Jewell, Simon 10:45 a.m. to 12:40 p.m. 142 Gerberding Hall FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Brotman, Jewell, Simon 1:00 p.m. Petersen Room REGULAR MEETING OF BOARD OF Allen Library REGENTS 2:15 to 4:00 p.m. Foege Building TOUR DEPARTMENT OF BIOENGINEERING To request disability accommodation, contact the Disability Services Office at: 206.543.6450 (voice), 206.543.6452 (TTY), 206.685.7264 (fax), or email at [email protected]. The University of Washington makes every effort to honor disability accommodation requests. Requests can be responded to most effectively if received as far in advance of the event as possible, preferably at least 10 days. 1.1/201-12 1/12/12 UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON BOARD OF REGENTS Academic and Student Affairs Committee Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles January 12, 2012 8:30 to 9:35 a.m. -

University of Washington Special Collections

UNIVERSITY CHRONOLOGY 1850 to 1859 February 28, 1854 Governor Isaac Ingalls Stevens recommended to the first territorial legislature a memorial to Congress for the grant of two townships of land for the endowment for a university. (“That every youth, however limited his opportunities, find his place in the school, the college, the university, if God has given him the necessary gifts.” Governor Stevens) March 22, 1854 Memorial to Congress passed by the legislature. January 29, 1855 Legislature established two universities, one in Lewis County and one in Seattle. January 30, 1858 Legislature repealed act of 1855 and located one university at Cowlitz Farm Prairies, Lewis County, provided one hundred and sixty acres be locally donated for a campus. (The condition was never met.) 1860 to 1869 December 12, 1860 Legislature passed bill relocating the university at Seattle on condition ten acres be donated for a suitable campus. January 21, 1861 Legislative act was passed providing for the selection and location of endowment lands reserved for university purposes, and for the appointment of commissioners for the selection of a site for the territorial university. February 22, 1861 Commissioners first met. “Father” Daniel Bagley was chosen president of the board April 16, 1861 Arthur A. Denny, Edward Lander, and Charles C. Terry deeded the necessary ten acres for the campus. (This campus was occupied be the University until 1894.) May 21, 1861 Corner stone of first territorial University building was laid. “The finest educational structure in Pacific Northwest.” November 4, 1861 The University opened, with Asa Shinn Mercer as temporary head. Accommodations: one room and thirty students. -

Diversity Without Integration Kevin Woodson University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2016 Diversity Without Integration Kevin Woodson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Woodson, Diversity Without Integration, 120 Penn State L. Rev. 807 (2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diversity Without Integration Kevin Woodson* Abstract The de facto racial segregation pervasive at colleges and universities across the country undermines a necessary precondition for the diversity benefits embraced by the Court in Grutter-therequirement that students partake in high-quality interracial interactions and social relationships with one another. This disjuncture between Grutter's vision of universities as sites of robust cross-racial exchange and the reality of racial separation should be of great concern, not just because of its potential constitutional implications for affirmative action but also because it reifies racial hierarchy and reinforces inequality. Drawing from an extensive body of social science research, this article explains that the failure of schools to achieve greater racial integration in campus life perpetuates harmful racial biases and exacerbates racial disparities in social capital, to the disadvantage of black Americans. After providing an overview of de facto racial segregation at America's colleges and making clear its considerable long-term costs, this article calls for universities to modify certain institutional policies, practices, and arrangements that facilitate and sustain racial separation on campus. -

It's My Retirement Money--Take Good Care of It: the TIAA-CREF Story

INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF USE TIAA-CREF and the Pension Research Council (PRC) of the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, are pleased to provide this digital edition of It's My Retirement Money—Take Good Care Of It: The TIAA-CREF Story, by William C. Greenough, Ph.D. (Homewood, IL: IRWIN for the Pension Research Council of the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, 1990). The book was digitized by TIAA-CREF with the permission of the Pension Research Council, which is the copyright owner of the print book, and with the permission of third parties who own materials included in the book. Users may download and print a copy of the book for personal, non- commercial, one-time, informational use only. Permission is not granted for use on third-party websites, for advertisements, endorsements, or affiliations, implied or otherwise, or to create derivative works. For information regarding permissions, please contact the Pension Research Council at [email protected]. The digital book has been formatted to correspond as closely as possible to the print book, with minor adjustments to enhance readability and make corrections. By accessing this book, you agree that in no event shall TIAA or its affiliates or subsidiaries or PRC be liable to you for any damages resulting from your access to or use of the book. For questions about Dr. Greenough or TIAA-CREF's history, please email [email protected] and reference Greenough book in the subject line. ABOUT THE AUTHOR... [From the original book jacket] An economist, Dr. Greenough received his Ph.D. -

The Black Power Movement and the Black Student Union (Bsu)

THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT AND THE BLACK STUDENT UNION (BSU) IN WASHINGTON STATE, 1967-1970 BY MARC ARSELL ROBINSON A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Program of American Studies AUGUST 2012 © Copyright by Marc Arsell Robinson, 2012 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by MARC ARSELL ROBINSON, 2012 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of MARC ARSELL ROBINSON find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _________________________________ David J. Leonard, Ph.D., Chair _________________________________ Lisa Guerrero, Ph.D. _________________________________ Thabiti Lewis, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT As I think about this dissertation and all the people who played some part in its creation, it is hard to know who to thank first. Yet, perhaps it would be fitting to begin with my dissertation chair, David J. Leonard, whose outstanding mentorship and support has been instrumental to this project. In addition, I was also honored to have Lisa Guerrero and Thabiti Lewis serve on my committee, therefore their service has also been appreciated. Several other Washington State University faculty and staff have made major contributions to my growth and development in the American Studies Ph.D. program including C. Richard King, chair of the Critical Culture Gender and Race Studies (CCGRS) Department, Rory Ong, director of the American Studies Program, and Rose Smetana, Program Coordinator for CCGRS. Moreover, all the faculty and staff of Comparative Ethnic Studies, Women Studies, and other departments/programs who worked with me deserve special acknowledgement for providing invaluable knowledge and guidance. -

Defunis V. Odegaard, Etc

(v(J.LI / Court Was.h ...Sup.reme. C.t. Voted on .................. , 19 .. Argued ................... , 19 .. Assigned .................. , 19 . No. 73-235 Submitted . ....... ...... , 19 .. Announced ................ , 19 . MARCO DE FUNIS, ET AL., Appellants vs. CHARLES ODEGAARD, PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, ET AL. /~i ~,,4_~/1/ fo a-dlZ~~ II 1 U-b·-tl~r..-t--1 \ w.- &;__;rv HOLD CERT. JURISDICTIONAL MERITS MOTION AB- NOT FOR 1----.--i----.-ST_A_T-,EMr-E_N_T..----+--.---l---.---ISENT VOT- o D N POST DIS AFF REV AFF 0 D ING Rehnquist, J . ..... .......... Powell, J ... .. ... ....... Blackmun, J ................. Marshall, J . ................. White, J ..................... Stewart, J ................... Brennan, J ................... Douglas, J .................... Burger, Ch. J .... ........... ,. October 12, 1973 JBO L b- ~ l>- ~ fl1 b1S- r ~~~~~~ ~~~.4.--~~ ~Lf2y~~ ' ~ ~ . ~~~~~'1~ 1~ LUo~~5 cf ~ ~~ lll<.J._ ~fy "-( 1/lu_ ~~~ 61~ ~s-f~~~ ~ &-/ ~ ~~ ~llLSCUSS C2-z_ -~ ~ ~ ~ G,._.,f, ~ ~ ~!uuf() ~ ~ ~ ~- .L-<.-- ~- ~~~c ·CI-~~J~ of~~:~~ ~~,'-'k-~~ o-r -~~~f-/ ~~ - ~ ~ ~ ~~~ ( pfd£:...,-:2-r_~/-r._.&~ ~~~~¥ ~1--r~of~ P~~~-z_~~, No. 73-235 SUPPLEMEMTAL MEMO De Funis, et al. v. Odegaard 1. I think this case is pro~~y ~ot. This is not a class action. The plaintiffs were the student, fuis wife an~s~. The student was, pursuant to the order of the state trial court, admitted to the law ~ school he desired to attend over a year ago. He may well graduate before this Court could hear this case. Given that De-- Funis-------....___ can no ___ longer_ __prove_ injury,--- I think--- he's the wrong plaintiff to assert the constitutional issue he wants to have resolved. -2- 2, This is not,. -

Making Citizen-Soldiers

MAKING CITIZEN-SOLDIERS Exam Copy Copyright © 2000 The President and Fellows of Harvard College Exam Copy Copyright © 2000 The President and Fellows of Harvard College MICHAEL S. NEIBERG Making Citizen-Soldiers ROTC and the Ideology of American Military Service HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England Exam Copy Copyright © 2000 The President and Fellows of Harvard College Copyright © 2000 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Second printing, 2001 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Neiberg, Michael. Making citizen-soldiers : ROTC and the ideology of American military service / Michael S. Neiberg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-674-54312-2 (cloth) ISBN 0-674-00715-8 (pbk.) 1. United States. Army. Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. 2. United States. Air Force ROTC. 3. United States. Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps. 4. United States—Armed Forces—Officers—Training of. I. Title. U428.5.N45 2000 355.2Ј232ЈExam071173—dc21 99-044354 Copy Copyright © 2000 The President and Fellows of Harvard College To the memory of Ethel Neiberg and Renee Saroff Oliner Exam Copy Copyright © 2000 The President and Fellows of Harvard College Exam Copy Copyright © 2000 The President and Fellows of Harvard College Acknowledgments In completing this book I have accumulated debts that I cannot hope to re- pay. The deepest of these debts is to my wife, Barbara, who has had to live with this project almost as long as she has had to live with me. I will be for- ever grateful for her patience and understanding. -

Alumni Magazine • Sep 11

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE • SEP 11 O U R F U T U R E YEARS Discovering what lies ahead EST. 18 61 of the UW’s 150th Birthday Together we make history. Discover what’s next. In 1914, William Boeing (right) rode an airplane for the first time and a dream was born. But before he could design planes, Boeing needed aeronautical engineers. So he partnered with the University of Washington … and the rest is history. Together, William Boeing and the University of Washington created an entire industry out of thin air, and proved the sky was no limit. Tell us your stories and learn more at uw.edu/150. The UW thanks our 150th sponsors: < This Issue > September 2011 The University of Washington Alumni Magazine 24 Out In The Open Rick Welts, ’75, is the first pro sports executive to declare his sexual orientation 28 Our Future Discovering what lies ahead of the UW’s 150th birthday 34 Treating War’s Hidden Injuries Gen. Peter Chiarelli, ’80, says communities are the key Prelude 4 Letters to the Editor 5 President’s Page 6 First Take 8 Face Time 10 The Hub 12 Findings 20 Alumni Homepage 42 LOCAL ROOTS Alumnotes 46 Wxyz 51 GLOBAL REACH THAT STATEMENT embodies the University of Washington, which this fall will mark a major milestone—its 150th anniversary. Since opening its doors in 1861, the UW has become a world leader on many fronts, generating health-care breakthroughs, produc- ing more Peace Corps volunteers than any other university and educating generations of leaders. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 COMMUNITIES IN CONFLICT: COMPOSITION, RACIAL DISCOURSE, AND THE ‘60S "REVOLUTION" DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Timothy Paul Barnett, M.A. -

Humanities: State Agencies (September 15, 1975) Humanities, Subject Files I (1973-1996)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Education: National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities: State Agencies (September 15, 1975) Humanities, Subject Files I (1973-1996) 1975 Humanities: State Agencies (September 15, 1975): Report 02 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/pell_neh_I_32 Recommended Citation "Humanities: State Agencies (September 15, 1975): Report 02" (1975). Humanities: State Agencies (September 15, 1975). Paper 4. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/pell_neh_I_32/4http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/pell_neh_I_32/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Education: National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities, Subject Files I (1973-1996) at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Humanities: State Agencies (September 15, 1975) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES WASHINGTON, D.C. 20506 COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP LISTS DIVISION OF PUBLIC PROGRAMS STATE-BASED PROGRAM October 1975 • -2- ALABAMA Malcolm Smith Architect 1919 Monticello Rd. Florence, Alabama 35630 Julia Tidwell Chairman Division of Humanities Stillman College P. o. Box 4898 Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35401 Mary George Waite President Farmers & Merchants Bank Centre, Alabama 35960 Barney Weeks Alabama Labor Council 231 w. Valley Ave. Birmingham, Alabama 35209 Clyde Williams President Miles College Birmingham, Alabama 35208 *Chairman STAFF: Jack Geren. Executive Director Alabama Committee for the Humanities and Public Policy Box 700 Birmingham-Southern College Birmingham, Alabama 35204 10/3/75 • ALABAMA COMMITTEE FOR THE HUMANITIES AND PUBLIC POLICY MEMBERS: James K. Baker Mrs. A. G. Gaston Attorney President 1630 Fourth Avenue Booker T. Washington Business Birmingham, Alabama 35203 College P. -

The University of Washington Alumni Magazine June

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE JUNE 1 What does 5 mean? UWAA MEMBERS DEFINE It’s WHAT IT MEANS TO BE A UW ALUM Pride It’s the feeling in your chest when Huskies show their excellence in any endeavor—in the classroom, on the field or in the community. You’re proud to be connected to the UW; proud to be part of a legacy that has endured for generations. UWAA MEMBERS THOMAS, ‘05, WHITNEY, ‘07, JOSEPH, ‘13 ‘07, JOSEPH, ‘05, WHITNEY, UWAA MEMBERS THOMAS, Define Alumni BE A MEMBER UWALUM.COM/DEFINE 2 COLUMNS MAGAZINE JUNE 2015 3 HUSKY PICKS FOR SUMMER Be a Dawg Driver Surfs Up! Real Dawgs Wear Purple and their Dawg paddle your way cars do, too! Purchase a Husky to fandom in comfy UW plate and $28 goes to the UW boardshorts. These fresh General Scholarship Fund annually. and functional boardies Show your Husky pride and be feature mesh lining, an a world of good. elastic and tie waist, and uw.edu/huskyplates a great price so you won’t have to fl oat a loan. fanatics.com Dawgfathers Purple, the New Black Honor your dad with a classy gift this Be fashionably purple in these sporty Father’s Day. Enameled cuff links and and sophisticated shorts or skirt a Washington watch are the perfect performance pieces. Tail Activewear way to dignify your dad. off ers stylish fan inspired choices that nordstrom.com are popular with women of all shapes, sizes and ages. ubookstore.com/thehuskyshop Color ‘Em Purple Lap Dawg Elevate your game and fl ash your true Hit the pool with a tsunami of Husky spirit colors this summer with ultimate purple in a Washington swim cap and polarized and gold nail polish. -

University of Michigan History

University of Michigan History Table of Contents Guides ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 Academics ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Administration .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Alumni ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Athletics .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Buildings & Grounds .............................................................................................................................. 11 Faculty .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Students ................................................................................................................................................... 16 Units ........................................................................................................................................................ 18 Timelines ...................................................................................................................................................