First War on Terror,” 1968-1970 Michael Gauvreau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebalanced and Revitalized: a Canada Strong

Rebalanced and Revitalized A Canada Strong and Free Mike Harris & Preston Manning THE FRASER INSTITUTE 2006 Copyright ©2006 by The Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The authors have worked independently and opinions expressed by them are, therefore, their own, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the supporters or the trustees of The Fraser Institute. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessary represent those of the Montreal Economic Institute or the members of its board of directors. This publication in no way implies that the Montreal Economic Institute or the members of its board of directors are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill. Series editor: Fred McMahon Director of Publication Production: Kristin McCahon Coordination of French publication: Martin Masse Design and typesetting: Lindsey Thomas Martin Cover design by Brian Creswick @ GoggleBox Editorial assistance provided by White Dog Creative Inc. Date of issue: June 2006 Printed and bound in Canada Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Harris, Mike, 945- Rebalanced and revitalized : a Canada strong and free / Mike Harris & Preston Manning Co-published by Institut économique de Montréal. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0–88975–232–X . Canada--Politics and government--2006-. 2. Government information-- Canada. 3. Political participation--Canada. 4. Federal-provincial relations-- Canada. 5. Federal government--Canada. I. Manning, Preston, 942- II. Fraser Institute (Vancouver, B.C.) III. Institut économique de Montréal IV. -

SAVE the DATE William Tetley Memorial Symposium, June 19, 2015

Français SAVE THE DATE William Tetley Memorial Symposium, June 19, 2015 The Canadian Maritime Law Association is pleased to invite you to attend a one-day legal symposium to celebrate the contribution of the late Professor William Tetley to maritime and international law and to Quebec society as a Member of the National Assembly and Cabinet Minister and as a great humanist. Details of the program will be communicated shortly. CLE accreditation of the symposium for lawyers is expected. Date: Friday, June 19, 2015 Time: 8h30 -16h30 followed by a Cocktail Reception Place: Law Faculty, McGill University, Montreal, Canada William Tetley, CM, QC Speakers: George R. Strathy, Chief Justice of Ontario Nicholas Kasirer, Quebec Court of Appeal Marc Nadon. Federal Court of Appeal Sean J. Harrington, Federal Court of Canada Prof. Sarah Derrington, The University of Queensland Prof. Dr. Marko Pavliha, University of Ljubljana Prof. Catherine Walsh, McGill University Chris Giaschi, Giaschi & Margolis Victor Goldbloom, CC, QC John D. Kimball, Blank Rome Patrice Rembauville-Nicolle, RBM2L Robert Wilkins More speakers to be confirmed shortly. Cost (in Canadian funds): CMLA Members: $250 Non-members: $300 Accommodations: For those of you from out of town wishing to attend, please note that a block of rooms has been reserved at the Fairmont The Queen-Elizabeth Hotel at a rate of $189 (plus taxes). Please note that the number of rooms is limited and use the following reference no.: CMLA0515. For reservations, tel. (toll- free): 1-800-441-1414 (Canada & USA) or 1-506-863-6301 (elsewhere); or visit https://resweb.passkey.com/go/cmla2015. -

Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: a 10-Year Democratic Audit 2014 Canliidocs 33319 Adam M

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 67 (2014) Article 4 Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: A 10-Year Democratic Audit 2014 CanLIIDocs 33319 Adam M. Dodek Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Dodek, Adam M.. "Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: A 10-Year Democratic Audit." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 67. (2014). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol67/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Reforming the Supreme Court Appointment Process, 2004-2014: A 10-Year Democratic Audit* Adam M. Dodek** 2014 CanLIIDocs 33319 The way in which Justice Rothstein was appointed marks an historic change in how we appoint judges in this country. It brought unprecedented openness and accountability to the process. The hearings allowed Canadians to get to know Justice Rothstein through their members of Parliament in a way that was not previously possible.1 — The Rt. Hon. Stephen Harper, PC [J]udicial appointments … [are] a critical part of the administration of justice in Canada … This is a legacy issue, and it will live on long after those who have the temporary stewardship of this position are no longer there. -

Mcgill's FACULTY of LAW: MAKING HISTORY

McGILL’S FACULTY OF LAW: MAKING HISTORY FACULTÉ DE DROIT FACULTY OF LAW Stephen Smith Wins Law’s Fourth Killam Comité des jeunes diplômés : dix ans déjà! Breaking the Language Barrier: la Facultad habla español Boeing Graduate Fellowships Take Flight Une année dynamique pour les droits de la personne CREDITS COVER (clockwise from top): the 2007-2008 Legal Methodology teaching assistants; three participants at the International Young Leaders Forum (p. 27); James Robb with friends and members of the Faculty Advisory EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Board (p. 10); Killam winners Stephen Scott, H. Patrick Glenn and Roderick Macdonald (p. 22); announcement of the Boeing Fellowships (p. 13); Human Rights Working Group letter-writing campaign (p. 6). Derek Cassoff Jane Glenn Diana Grier Ayton Toby Moneit-Hockenstein RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF Lysanne Larose EDITOR Mark Ordonselli 01 Mot du doyen CONTRIBUTORS 03 Student News and Awards Andrés J. Drew Nicholas Kasirer 06 A Lively Year for the Human Lysanne Larose Rights Working Group Maria Marcheschi 06 Seven Years of Human Rights Neale McDevitt Internships Toby Moneit-Hockenstein Mark Ordonselli 08 The Career Development Jennifer Smolak Office and You WHERE ARE OUR Pascal Zamprelli 09 Dix ans déjà! ALUMNI-IN-LAW? CORRECTEUR D’ÉPREUVE 10 The James Robb Award Peter Pawelek 11 Les Prix F.R. Scott de service PHOTOGRAPHERS exemplaire Claudio Calligaris Owen Egan 12 New Hydro-Québec Scholars Paul Fournier in Sustainable Development Kyle Gervais 13 Boeing Gives Legal Lysanne Larose Maria Marcheschi Scholarship Wings -

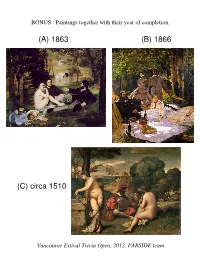

1866 (C) Circa 1510 (A) 1863

BONUS : Paintings together with their year of completion. (A) 1863 (B) 1866 (C) circa 1510 Vancouver Estival Trivia Open, 2012, FARSIDE team BONUS : Federal cabinet ministers, 1940 to 1990 (A) (B) (C) (D) Norman Rogers James Ralston Ernest Lapointe Joseph-Enoil Michaud James Ralston Mackenzie King James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent 1940s Andrew McNaughton 1940s Douglas Abbott Louis St. Laurent James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent Brooke Claxton Douglas Abbott Lester Pearson Stuart Garson 1950s 1950s Ralph Campney Walter Harris John Diefenbaker George Pearkes Sidney Smith Davie Fulton Donald Fleming Douglas Harkness Howard Green Donald Fleming George Nowlan Gordon Churchill Lionel Chevrier Guy Favreau Walter Gordon 1960s Paul Hellyer 1960s Paul Martin Lucien Cardin Mitchell Sharp Pierre Trudeau Leo Cadieux John Turner Edgar Benson Donald Macdonald Mitchell Sharp Edgar Benson Otto Lang John Turner James Richardson 1970s Allan MacEachen 1970s Ron Basford Donald Macdonald Don Jamieson Barney Danson Otto Lang Jean Chretien Allan McKinnon Flora MacDonald JacquesMarc Lalonde Flynn John Crosbie Gilles Lamontagne Mark MacGuigan Jean Chretien Allan MacEachen JeanJacques Blais Allan MacEachen Mark MacGuigan Marc Lalonde Robert Coates Jean Chretien Donald Johnston 1980s Erik Nielsen John Crosbie 1980s Perrin Beatty Joe Clark Ray Hnatyshyn Michael Wilson Bill McKnight Doug Lewis BONUS : Name these plays by Oscar Wilde, for 10 points each. You have 30 seconds. (A) THE PAGE OF HERODIAS: Look at the moon! How strange the moon seems! She is like a woman rising from a tomb. She is like a dead woman. You would fancy she was looking for dead things. THE YOUNG SYRIAN: She has a strange look. -

PERIOD 1 (CHONG): Trial of the Pms Schedule June 2006

Trials of the PMs Schedule Date Trial CHARGE Prosecution Prosecution Defence Defence Witnesses Judge PM Name Witnesses Mon Jan 10 Robert Decision to institute the Wartime Abdullah Karen (Wilfrid Laurier) Naeem Sukhpreet (Nelly Victor Mr. N Borden Elections Act McClung) Causing division by forcing Samuel Byron (Henri Bourassa) Krunal Garry (Sir Sam Hughes) conscription on the country Internment of Enemy Aliens Brandon Justin (Stefan Galant) Kayne Edward L.(William Otter) Tues Jan 11 Mackenzie Racial Discrimination in turning Peter Brianna (Captain Gustav Edward L. Kayne (Frederick Blair) Abdullah Samuel King away the SS St. Louis Schroeder) Ineffective leadership in the Byron Luxman (James Ralston) Sherry Nelson (Andrew policy of Conscription in WWII McNaughton) Unjust Internment of Japanese Garry Krunal (David Suzuki) Sharon Jason (John Hart) Canadians Wed Jan 12 John Unjustified in cancelling the Nelson Edward F. (Crawford Justin Brandon (General Guy Jayna Mr. N. Diefenbaker Avro Arrow Gordon Jr.) Simonds) Failure to act decisively during Mihai Kayne (John F. Kennedy) Jason Sharon (Howard Green) Cuban Missile Crisis Failed to secure Canada by not Mihai Sherry (Douglass Luxman Victor (Howard Green) arming Bomarc Missiles with Harkness) nuclear warheads Thurs Jan 13 Pierre Unjustified invoking of the War Stefani Sherry (Tommy Douglas) Victor Luxman (Robert Brianna Mr. N. Trudeau Measures Act in October Crisis Bourassa) Ineffective policy of the 1980 Keara Kayne (Peter Lougheed) Edward F. Abdullah (Marc Lalonde) National Energy Program Failure to get Quebec to sign the Jayna Byron (Rene Levesque) Maggie Jenise (Bill Davis) Constitution Act in 1982 Fri Jan 14 Brian Weakened Canada’s economy Brianna Jayna (Paul Martin) Annie Stefani (Michael Wilson) Kayne Mr. -

Un Plan De Developpement Pour La Gaspesie Et Le Bas-Saint-Laurent

ol. 4, numero 5, mai 1983 MON1-3011 C S 4404 - PECH UN PLAN DE DEVELOPPEMENT POUR LA GASPESIE ET LE BAS-SAINT-LAURENT Le gouvernement canadien a annonce au debut de mai un programme special de developpement de la Gaspesie et du Bas-Saint-Laurent de 224,5 millions $, repartis sur 5 ans, dont 71 millions $ pour le secteur des peches. Cette annonce a ete faite a Matane devant les organismes regionaux par les ministres Pierre De Bane, Marc Lalonde et Herb Gray, accom- pagnes des deputes de la region. AU SOMMAIRE D'autres ameliorations au havre de Matane 7 224,5 millions $ pour la region du Un centre de recherche a Mont-Joli 8 Bas-Saint-Laurent/Gaspesie 2 71 millions $ pour le developpement Un nouveau havre de !Ache a Cap-Chat 9 des 'Aches en Gaspesie 3 Six nouveaux projets de developpement La formation en p8che: un choix de carrieres 10 4 dans le comte de Gaspe Lancement de la phase II du programme PERIO : ants travaux a Gascons, federal de developpement economique SH defroi et Bonaventure 6 des Iles-de-la-Madeleine 12 223 E57 224,5 MILLIONS $ POUR LA REGION DU BAS-SAINT-LAURENT/GASPESIE Le gouvernement canadien a initiatives issues du milieu ainsi Un connite executif regroupant les annonce au debut de mai un pro- que les frais d'administration du differents ministeres sera tree sous gramme special de developpement Plan. la presidence du coordonnateur de la Gaspesie et du Bas-Saint- federal du developpement econo- Le gouvernement favorisera les Laurent de 224,5 millions $ repartis mique pour le Quebec, M. -

RA 2002-Mc-Complet-AN

McCORD MUSEUM Annual Report 2001 | 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Report from the Chairman, Board of Trustees 4 Report from the Executive Director 5 Museum Mandate 5 Report from the Treasurer 6 Board of Trustees and Officers 7 Exhibitions 8 Acquisitions 10 Donors to the Collections 13 Programming and Community Events 14 16 Financial Statements Annual Giving Campaigns 23 Committees, Board of Trustees 25 Volunteers 26 Activities and Special Events 27 Scholarly Activities 31 Staff 35 Sponsors and Partners 38 The McCord Museum is grateful to the following government agencies for providing the Museum’s core funding: the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications du Québec; the Archives nationales du Québec; and the Arts Council of Montreal McCORD MUSEUM Annual Report 2001 | 2002 Across Borders at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, December 2001-May 2002. REPORT FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD The 2001-2002 “Museum Year” was one At the McCord’s annual meeting in June 2001, of steady growth and new initiatives. Allow me the Board said adieu to trustee Elsebeth Merkly and to highlight some of them here: committee members Henriette Barbeau and David Hannaford. I would like to express the Museum’s › the completion of a review of the Museum’s medium- appreciation to these individuals for their important term Strategic Priorities for programming, staªng and contributions to the work of the McCord. At the same physical facilities by an ad-hoc task group of trustees time we welcomed Gail Johnson, Bernard Asselin and and senior sta¤; John Peacock as newly elected trustees. -

Loyola of Montreal: Report of the President 1969 to 1973 Index

Loyola of Montreal: Report of the President 1969 to 1973 Index 1969-1971 1972-1973 Report of the President . 5 Report of the President ... ... ..... .... 41 Reports Reports Registrar .... ... .. .. ..... .. ... 11 Registrar ..... .. .. ..... .. .. .... 46 Evening Division ... ...... ... .... 12 Evening Division ... .. ......... 47 Chief Librarian .. .. .... .... .. .. 12 Chief Librarian . .... .. .. ... ...... 48 Physical Education and Athletics . ..... 14 Chaplaincy .. ... ... ...... .. .. .. 49 Financial Aid . .. .... ... .... .. 15 Physical Education and Athletics . .. 49 Development .. ....... .... ... ..... 15 Alumni ... .. ...... .. .. ... ... .. 49 Financial .. .. .. ..... .. ....... .. 15 Financial Aid ..... .. .. .. .. .. 50 Senate Committee on Visiting Lecturers 16 Development ... .... ... .... .. .. ... 50 Faculty Financial ....... .... .. .. .. ... .. 50 awards . ... ... ... ... ....... .. ... 16 Senate Committee on Visiting Lecturers 51 publications, lectures, speeches . .... 17 Faculty doctorates, appointments, promotions . 20 awards .. .. ... ..... ........... 51 new faculty, faculty on leave of publications, lectures, speeches .. ..... 51 absence, departures . ..... .. ...... 21 doctorates, appointments, promotions . 53 new faculty, faculty on leave of absence, departures . ... .. ... ... 54 1971-1972 Report of the President . 24 Reports Registrar . .. .. ... ..... .. .. .... 31 Evening Division ..... ... ......... .. 32 Chief Librarian .... ........ ... ... 32 Chaplaincy . .... ... ... ..... 34 Physical Education and Athletics -

Trudeau, Constitutionalism, and Family Allowances Raymond Blake

Document generated on 09/26/2021 5:01 p.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Intergovernmental Relations Trumps Social Policy Change: Trudeau, Constitutionalism, and Family Allowances Raymond Blake Volume 18, Number 1, 2007 Article abstract Family allowances were one of the few programs shared by all Canadian URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/018260ar families from 1945 to 1992, and one of the few means of building social DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/018260ar cohesion across Canada. Family allowances became embroiled in the minefield of Canadian intergovernmental relations and the political crisis created by the See table of contents growing demands from Quebec for greater autonomy from the federal government in the early 1970s. Ottawa initially dismissed Quebec’s demands for control over social programs generally and family allowance in particular. Publisher(s) However, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau offered family allowance reforms as a means of enticing Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa to amend the British The Canadian Historical Association/La Société historique du Canada North America Act. The government’s priority was constitutional reform, and it used social policy as a bargaining chip to achieve its policy objectives in that ISSN area. This study shows that public policy decisions made with regard to the family allowance program were not motivated by the pressing desire to make 0847-4478 (print) more effective policies for children and families. 1712-6274 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Blake, R. (2007). Intergovernmental Relations Trumps Social Policy Change: Trudeau, Constitutionalism, and Family Allowances. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 18(1), 207–239. -

The Mulroney-Schreiber Affair - Our Case for a Full Public Inquiry

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA THE MULRONEY-SCHREIBER AFFAIR - OUR CASE FOR A FULL PUBLIC INQUIRY Report of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Paul Szabo, MP Chair APRIL, 2008 39th PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Communication Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 THE MULRONEY-SCHREIBER AFFAIR - OUR CASE FOR A FULL PUBLIC INQUIRY Report of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Paul Szabo, MP Chair APRIL, 2008 39th PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION STANDING COMMITTEE ON ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PRIVACY AND ETHICS Paul Szabo Pat Martin Chair David Tilson Liberal Vice-Chair Vice-Chair New Democratic Conservative Dean Del Mastro Sukh Dhaliwal Russ Hiebert Conservative Liberal Conservative Hon. Charles Hubbard Carole Lavallée Richard Nadeau Liberal Bloc québécois Bloc québécois Glen Douglas Pearson David Van Kesteren Mike Wallace Liberal Conservative Conservative iii OTHER MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT WHO PARTICIPATED Bill Casey John Maloney Joe Comartin Hon. Diane Marleau Patricia Davidson Alexa McDonough Hon. Ken Dryden Serge Ménard Hon. -

A New Perspective on Public Health

This is Public Health: A Canadian History A New Perspective on Public Health A New Perspective on Public Health . .8 .1 After .22 .years .of .expansion .in .Canada’s .health . services, .the .1970s .began .with .a .period .of . Environmental Concerns . 8 .3 consolidation, .rationalization .and .reduced . federal .funding .for .health .care . .Industrialized . Motor Vehicle Safety . 8 .4 countries .began .to .recognize .that .the .substantial . Physical Activity . 8 .4 declines .in .mortality .achieved .over .the .last .100 . years .were .largely .due .to .improvements .in .living . People with Disabilities . 8 .6 standards .rather .than .medical .advancements . This .brought .a .rethinking .of .health .systems . Chronic Disease . .8 .7 in .the .1970s .and .1980s, .initiating .a .period . A Stronger Stand . .8 .7 of .Canadian .innovation .and .leadership .in . new .approaches .to .health .promotion .with .an . The Lalonde Report . 8 .8 impact .both .at .home .and .abroad . .Concerns . about .the .environment, .chronic .diseases, .and . Expanding Interests . 8 .10 the .heavy .toll .of .motor .vehicle .collisions .were . growing, .as .were .new .marketing .approaches .to . Tobacco . 8 .12 deliver .the .“ounce .of .prevention” .message .to . Infectious Diseases . 8 .14 the .public . .Researchers .developed .systematic . methodologies .to .reduce .risk .factors .and .applied . A New Strain of Swine Flu . 8 .16 an .epidemiological .approach .to .health .promotion . by .defining .goals .and .specific .objectives .1 Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) . 8 .17 At .the .beginning .of .the .1970s, .federal .and . Global Issues . 8 .19 provincial .governments .were still. .analyzing .the . Primary Health Care— 348 .recommendations of. .the .two-year .National . Task .Force .on .the .Cost .of .Health .Services, . Health for All by 2000 .