Recent Developments in Climate Change Policy in Japan and a Discussion of Energy Efficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3 Japan's Foreign Policy to Promote National and Worldwide

Japan’s Foreign Policy to Promote National and Worldwide Interests Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Japan’s Foreign Policy to Promote National and Worldwide Interests 1. Efforts for Peace and Stability of Japan and the International Community Current Status of the Security Environment Surrounding Japan Korea nevertheless proceeded to conduct its third The security environment surrounding Japan is nuclear tests in February 2013. North Korea’s continued becoming increasingly severe. Amid progressively nuclear and missile development further exacerbates the greater presence of emerging countries in the threat to security in the region, seriously undermining international community, the power balance has been the peace and stability of the international community, changing, and this has substantially influenced the and cannot be tolerated. China’s moves to strengthen dynamics of international politics. The advancement its military capabilities without sufficient transparency, of globalization and rapid progress in technological and its rapidly expanded and intensified activities at innovation have invited a change in the relative influence sea and in the air, are matters of concern for the between states and non-state actors, increasing threats region and the international community. In January of terrorism and other crimes by non-state actors 2013, there was an incident in which a Chinese warship that undermine national security. The proliferation of directed its fire control radar at vessel of JMSDF (Japan weapons of mass destruction and other related materials Maritime Self-Defense Force), and in November, China also remains a threat. In addition, risks, to the global unilaterally established and announced the “East China commons, such as seas, outer space and cyberspace, Sea Air Defense Identification Zone.” These actions have been spreading and becoming more serious. -

JAPAN Auf Einen BLICK Nr. 171: Februar 2013

JAPAN AUF EINEN BLICK Februar 2013 Das Monatsmagazin des Konsulats von Japan in Hamburg Ausgabe 171 / Februar 2013 Japan lädt ein Sayonara Berichte zum Empfang anlässlich des Mai Fujii, Researcher/Adviser, blickt Geburtstages S.M. des Kaisers sowie auf ihre zweijährige Dienstzeit in über den Neujahrsempfang…..Seite.02 Hamburg zurück.……………..Seite.05 Wahlergebnisse Ankurbeln Unterhauswahlen vom 16.12.2012 Die japanische Regierung bringt Kon- und neues Kabinett unter junkturpaket auf den Weg, um zum Premierminister Shinzo Abe…Seite.08 Wachstum zurückzukehren…Seite.10 Neujahrsfeste Stromnetz Hakuba-Club, DJG Winsen und DJG Mitsubishi und TenneT investieren in Hannover feiern Shinnenkai …Seite.11 Offshore-Netzanbindungen ..Seite.13 WAS ÜBRIG BLEIBT, Ehrung Termine BRINGT GLÜCK Hideki Fujii wird für seine vielfältigen http://www.hamburg.emb- Verdienste ausgezeichnet ..…Seite.15 japan.go.jp/downloads/termine.pdf Nokorimono niwa fuku ga aru JAPAN AUF EINEN BLICK Kultur- & Informationsbüro des Konsulats von Japan in Hamburg, Rathausmarkt 5, 20095 Hamburg, [email protected], www.hamburg.emb-japan.go.jp, Tel.: 040 333 0170, Fax: 040 303 999 15 REDAKTION Konsul Tomio Sakamoto (verantwortlich), Konsul Tatsuhiko Ichihara; Udo Cordes, Helga Eggers, Sabine Laaths, Marika Osawa, Saori Takano. JAPAN AUF EINEN BLICK erscheint zehnmal im Jahr und ist kostenlos als E-Letter zu beziehen. Alle hier veröffentlichten Artikel entsprechen nicht unbedingt der Meinung der japanischen Regierung oder des Konsulats von Japan in Hamburg. Redaktionsschluss ist der 15. des jeweiligen Vormonats. JAPAN AUF EINEN BLICK // Ausgabe 171 / Februar 2013 2 LEITARTIKEL Japan bittet zum Empfang Zwei große Empfänge im Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten in Hamburg, zu dem eng mit Japan verbundene Persönlichkeiten aus ganz Norddeutschland sowie das Hamburger Konsularkorps geladen waren, prägten das gesellschaftliche Leben Anfang Dezember des letzten Jahres und zum Jahresbeginn. -

Souhrnná Terirotální Informace Japonsko

SOUHRNNÁ TERITORIÁLNÍ INFORMACE Japonsko Souhrnná teritoriální informace Japonsko Zpracováno a aktualizováno zastupitelským úřadem ČR v Tokiu (Japonsko) ke dni 31. 8. 2016 18:03 Seznam kapitol souhrnné teritoriální informace: 1. Základní charakteristika teritoria, ekonomický přehled (s.2) 2. Zahraniční obchod a investice (s.13) 3. Vztahy země s EU (s.18) 4. Obchodní a ekonomická spolupráce s ČR (s.20) 5. Mapa oborových příležitostí - perspektivní položky českého exportu (s.29) 6. Základní podmínky pro uplatnění českého zboží na trhu (s.35) 7. Kontakty (s.48) 1/53 http://www.businessinfo.cz/japonsko © Zastupitelský úřad ČR v Tokiu (Japonsko) SOUHRNNÁ TERITORIÁLNÍ INFORMACE Japonsko 1. Základní charakteristika teritoria, ekonomický přehled Japonsko patří mezi vyspělé světové ekonomiky se stabilním právním prostředím. Je třetí největší světovou ekonomikou (po USA a Číně) a trhem s nejvyšším počtem bohatých domácností na světě. Japonsko skýtá dlouhou řadu exportních příležitostí, které dosud nebyly plně využity. Podkapitoly: 1.1. Oficiální název státu, složení vlády 1.2. Demografické tendence: Počet obyvatel, průměrný roční přírůstek, demografické složení (vč. národnosti, náboženských skupin) 1.3. Základní makroekonomické ukazatele za posledních 5 let (nominální HDP/obyv., vývoj objemu HDP, míra inflace, míra nezaměstnanosti). Očekávaný vývoj v teritoriu s akcentem na ekonomickou sféru. 1.4. Veřejné finance, státní rozpočet - příjmy, výdaje, saldo za posledních 5 let 1.5. Platební bilance (běžný, kapitálový, finanční účet), devizové rezervy (za posledních 5 let), veřejný dluh vůči HDP, zahraniční zadluženost, dluhová služba 1.6. Bankovní systém (hlavní banky a pojišťovny) 1.7. Daňový systém 1.1 Oficiální název státu, složení vlády Oficiální název státu: • Japonsko (japonsky: Nippon-koku či Nihon-koku, anglicky: Japan) Japonsko je konstituční monarchií s nejstarším parlamentním systémem ve východní Asii. -

Roster of Winners in Single-Seat Constituencies No

Tuesday, October 24, 2017 | The Japan Times | 3 lower house ele ion ⑳ NAGANO ㉘ OSAKA 38KOCHI No. 1 Takashi Shinohara (I) No. 1 Hiroyuki Onishi (L) No. 1 Gen Nakatani (L) Roster of winners in single-seat constituencies No. 2 Mitsu Shimojo (KI) No. 2 Akira Sato (L) No. 2 Hajime Hirota (I) No. 3 Yosei Ide (KI) No. 3 Shigeki Sato (K) No. 4 Shigeyuki Goto (L) No. 4 Yasuhide Nakayama (L) 39EHIME No. 4 Masaaki Taira (L) ⑮ NIIGATA No. 5 Ichiro Miyashita (L) No. 5 Toru Kunishige (K) No. 1 Yasuhisa Shiozaki (L) ( L ) Liberal Democratic Party; ( KI ) Kibo no To; ( K ) Komeito; No. 5 Kenji Wakamiya (L) No. 6 Shinichi Isa (K) No. 1 Chinami Nishimura (CD) No. 2 Seiichiro Murakami (L) ( JC ) Japanese Communist Party; ( CD ) Constitutional Democratic Party; No. 6 Takayuki Ochiai (CD) No. 7 Naomi Tokashiki (L) No. 2 Eiichiro Washio (I) ㉑ GIFU No. 3 Yoichi Shiraishi (KI) ( NI ) Nippon Ishin no Kai; ( SD ) Social Democratic Party; ( I ) Independent No. 7 Akira Nagatsuma (CD) No. 8 Takashi Otsuka (L) No. 3 Takahiro Kuroiwa (I) No. 1 Seiko Noda (L) No. 4 Koichi Yamamoto (L) No. 8 Nobuteru Ishihara (L) No. 9 Kenji Harada (L) No. 4 Makiko Kikuta (I) No. 2 Yasufumi Tanahashi (L) No. 9 Isshu Sugawara (L) No. 10 Kiyomi Tsujimoto (CD) No. 4 Hiroshi Kajiyama (L) No. 3 Yoji Muto (L) 40FUKUOKA ① HOKKAIDO No. 10 Hayato Suzuki (L) No. 11 Hirofumi Hirano (I) No. 5 Akimasa Ishikawa (L) No. 4 Shunpei Kaneko (L) No. 1 Daiki Michishita (CD) No. 11 Hakubun Shimomura (L) No. -

Japan's Political Turmoil in 2008: Background and Implications for The

Order Code RS22951 September 16, 2008 Japan’s Political Turmoil in 2008: Background and Implications for the United States Mark E. Manyin and Emma Chanlett-Avery Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary On September 1, 2008, Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda stunned observers by resigning his post, saying that a new leader might be able to avoid the “political vacuum” that he faced in office. Fukuda’s 11-month tenure was marked by low approval ratings, a sputtering economy, and virtual paralysis in policymaking, as the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) used its control of the Upper House of Japan’s parliament (the Diet) to delay or halt most government proposals. On September 22, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) will elect a new president, who will become Japan’s third prime minister in as many years. Ex-Foreign Minister Taro Aso, a popular figure known for his conservative foreign policy credentials and support for increased deficit spending, is widely expected to win. Many analysts expect that the new premier will dissolve the Lower House and call for parliamentary elections later in the fall. As a result, Japanese policymaking is likely to enter a period of disarray, which could negatively affect several items of interest to the United States, including the passage of budgets to support the realignment of U.S. forces in Japan and the renewal of legislation that authorizes the deployment of Japanese navy vessels that are refueling ships supporting U.S.-led operations in Afghanistan. This report analyzes the factors behind and implications of Japan’s current political turmoil. -

Japanische Innenpolitik: Schwerpunkte Und Tendenzen

Japanische Innenpolitik: Schwerpunkte und Tendenzen Japanese Domestic Policy 2008/09: Highlights and Tendencies Manfred Pohl Domestic policy in 2008 and the first half of 2009 was once again characterized by traditional as well as recent shortcomings of political culture in Japan. That is why this chapter has to discuss the desperate fight of the Asô government for political survival under the system. The growing rift in the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party and the New Kōmeitō is described as a clear signal of beginning decline of the half-century of nearly unbroken rule by the LDP. Electoral behavior of Kōmeitō (or rather Sōka gakkai) followers and electoral maneuvering of conservative stalwarts is discussed, as are relations between the LDP and the opposition party with the ministe- rial bureaucracy, which was deeply troubled in 2008 by plans both of the LDP and the DPJ to curb its predominant role. Regional and gubernatorial elections in 2008 are outlined as possible early indicators for the disastrous election defeat of both the LDP and the Kōmeitō. The chapter finally seeks to evaluate the guiding role of the imperial family in Japanese society by reflecting upon the golden anniversary of the marriage of the imperial couple. 1 Überblick Die Jahre 2008 und 2009 dürften in die Geschichte der japanischen Innenpolitik als eine Periode eines unaufhaltsamen Niedergangs der machtgewohnten Libe- 24 Innenpolitik raldemokraten verzeichnet werden. Die größte Regierungspartei LDP (Liberal- Demokratische Partei, Jiyū Minshutō) unterlag in diesem Zeitraum weiter einem inneren Zersetzungsprozess, in dem die traditionellen Herrschaftsstrukturen, die der Partei seit 1955 ein nahezu unangefochtenes Machtmonopol sicherten, zerfielen. -

Koizumi's Reform of Special Corporations Susan Carpenter

Journal of International Business and Law Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 2004 Koizumi's Reform of Special Corporations Susan Carpenter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl Recommended Citation Carpenter, Susan (2004) "Koizumi's Reform of Special Corporations," Journal of International Business and Law: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/jibl/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International Business and Law by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carpenter: Koizumi's Reform of Special Corporations THE JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS & LAW KOIZUMI'S REFORM OF SPECIAL CORPORATIONS By: Dr. Susan Carpenter* When Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi assumed office in April 2001 he pledged to initiate extensive structural reforms that would bring Japan's deflation-ridden economy back on track and renew consumer confidence. His mantra 'structural reform without sanctuary' brought memories of former Prime Ministers Morihiro Hosokawa and Maruyama's attempts at reforming the political and economic system during three turbulent years from 1993-1996. Koizumi's proposed reforms encompass three areas: (i) fiscal reforms; (ii) state-sector reforms; (iii) tackling the non-performing loans (NPL). He also promised to downgrade the Liberal Democratic Party, the party that has dominated national and local politics since 1955 and over which he presides as the president. Nearly three years later, despite Koizumi's efforts, the process of reform has occurred slowly, giving voters, who had high expectations that Japan's worst post-war recession would come to an end, the distinct impression that Koizumi's reforms may be more an image of the effort to reform. -

Ethics and Climate Change a Study of National Commitments

Ethics and Climate Change: A Study of National Commitments Ethics and Climate Change A Study of National Commitments Donald A. Brown and Prue Taylor (Eds.) IUCN Environmental Law Programme Environmental Law Centre Godesberger Allee 108-112 53175 Bonn, Germany Phone: ++ 49 228 / 2692 231 Fax: ++ 49 228 / 2692 250 [email protected] IUCN Environmental Policy and Law Paper No. 86 www.iucn.org/law IUCN World Commission on Environmental Law Ethics and Climate Change A Study of National Commitments Ethics and Climate Change A Study of National Commitments Donald A. Brown and Prue Taylor (Eds.) IUCN Environmental Policy and Law Paper No. 86 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland in collaboration with the IUCN Environmental Law Centre, Bonn, Germany Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Donald A. Brown and Prue Taylor (Eds.) (2015). Ethics and Climate Change. A Study of National Commitments IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. -

After the Earthquake Hit, the Governor of Iwate Prefecture Requested the Dispatch of Ground Self-Defense Force (SDF) Troops to Assist in Disaster Relief

& Gijs Berends (eds) Berends & Gijs Al-Badri Dominic AFTER THE How has Japan responded to the March 2011 disaster? What changes have been made in key domestic policy areas? GREAT EaST JAPAN The triple disaster that struck Japan in March 2011 began with the most powerful earthquake known to have hit Japan and led to tsunami reaching 40 meters in height that GREAFTER THE EaRTHQUAKE devastated a wide area and caused thousands of deaths. The ensuing accident at the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power POLITICAL AND POLICY CHANGE plant was Japan’s worst and only second to Chernobyl in its IN POST-FUKUSHIMA JAPAN severity. But has this triple disaster also changed Japan? Has it led to a transformation of the country, a shift in how Japan functions? This book, with fresh perspectives on extra- Edited by ordinary events written by diplomats and policy experts at European embassies to Japan, explores subsequent shifts A Dominic Al-Badri and Gijs Berends in Japanese politics and policy-making to see if profound T changes have occurred or if instead these changes have been Ea limited. The book addresses those policy areas most likely to be affected by the tragedy – politics, economics, energy, J ST climate, agriculture and food safety – describes how the sector has been affected and considers what the implications A are for the future. P A N N Ea RTHQU A KE www.niaspress.dk Al-Badri-Berends_cover.indd 1 12/02/2013 14:12 AFTER THE GREAT EaST JAPAN EaRTHQUAKE Al-Badri-Berends_book.indd 1 12/02/2013 14:29 ASIA INSIGHTS A series aimed at increasing an understanding of contemporary Asia among policy-makers, NGOs, businesses, journalists and other members of the general public as well as scholars and students. -

Japan Book Review Japan-UK Reviews Volume 2 No

japansociety Japan Book Review Japan-UK Reviews Volume 2 No. 6 December 2007 Issue No. 12 Editor: Sean Curtin Contents Managing Editor: Clare Barclay (1) Nemesis: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 n our final issue of 2007, we have some excellent reviews and previews (2) Nichi-Bei Dohmei-toiu of the latest Japan-related books hot off the printing press. Our first Riarizumu Iarticle looks at a major new work by Sir Max Hastings on the dramatic (3) Koizumi Kantei Hiroku final year that lead to Japan's wartime defeat. We also feature three recently (4) Kozo Kaikaku No Shinjitsu: published Japanese language books which offer insights into the Koizumi years and the US-Japan relationship. New reviewer William Farr offers his Takenaka Heizo Daijin Nisshi verdict on a Japanese hot springs book, there is also another riveting reader's (5) Getting Wet: Adventures in the review plus lots more reviews and previews. Finally, Japan Book Review says Japanese Bath a tearful farewell to our Managing Editor Clare Barclay. Clare has worked on (6) Divorce in Japan: Family, Japan Book Review for over two years and we could not have produced it Gender, and the State, 1600-2000 without her. Many thanks on the readers' behalf and we will miss you. (7) Reader's comments: Under the Sun Sean Curtin (8) North Korea in the 21st Century, New reviews: www.japansociety.org.uk/reviews.html An interpretative guide Archive reviews: http://www.japansociety.org.uk/reviews_archive.html (9) Preview: Outsourcing and Human Resource Management (10) Preview: Tokyo Look Book Japan Book Review Nemesis: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 by Max Hastings Harper Press, 2007, 673 pages including index, notes and bibliography, £25. -

UNU 40 Anniversary Symposium

UNU 40 th Anniversary Symposium – Summary Report OPENING REMARKS David M. Malone Rector, UNU; Under-Secretary-General, United Nations The symposium was opened by Dr. Malone. He emphasized that over the past 40 years UNU has been very fortunate to be hosted by Japan, and expressed appreciation to the Government of Japan for the funding it provides the university. He underlined the important role of young people in sustainable development, and mentioned that the students of UNU-IAS recently had the honour of meeting Their Majesties the Emperor and the Empress of Japan. Dr. Malone noted that UNU had contributed ideas to the SDGs process, through the publication of reports and policy briefs. The process itself was complicated and involved many different stakeholders, but the central actors were the member states who negotiated the agenda. Dr. Malone observed that international organizations often overstate their role in development, which is actually achieved by developing countries driving their own progress. Outside contributions can play a very important role, however. Noting how complicated the SDGs process had been, he suggested that its best component was the public consultation, in which millions of people had participated from across the globe. Dr. Malone observed that the SDGs do very well in articulating priority areas for progress in development, which is critical as no government can effectively prioritize all 169 targets. Local ownership can be very effective; if each government decides on a dozen (or even half a dozen) targets to prioritize, significant progress will be achieved. Dr. Malone suggested that despite the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, there were still two missing elements: successful outcomes to the Paris Climate Conference in November–December 2015, and the UN World Humanitarian Summit in May 2016. -

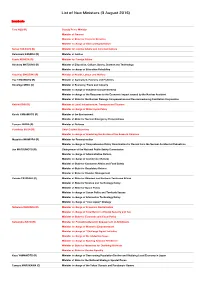

List of New Ministers (3 August 2016)

List of New Ministers (3 August 2016) Incumbents Taro ASO (R) Deputy Prime Minister Minister of Finance Minister of State for Financial Services Minister in charge of Overcoming Deflation Sanae TAKAICHI (R) Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications Katsutoshi KANEDA (R) Minister of Justice Fumio KISHIDA (R) Minister for Foreign Affairs Hirokazu MATSUNO (R) Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Minister in charge of Education Rebuilding Yasuhisa SHIOZAKI (R) Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare Yuji YAMAMOTO (R) Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Hiroshige SEKO (C) Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Minister in charge of Industrial Competitiveness Minister in charge of the Response to the Economic Impact caused by the Nuclear Accident Minister of State for the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation Keiichi ISHII (R) Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Minister in charge of Water Cycle Policy Koichi YAMAMOTO (R) Minister of the Environment Minister of State for Nuclear Emergency Preparedness Tomomi INADA (R) Minister of Defense Yoshihide SUGA (R) Chief Cabinet Secretary Minister in charge of Alleviating the Burden of the Bases in Okinawa Masahiro IMAMURA (R) Minister for Reconstruction Minister in charge of Comprehensive Policy Coordination for Revival from the Nuclear Accident at Fukushima Jun MATSUMOTO (R) Chairperson of the National Public Safety Commission Minister in charge of Administrative Reform Minister in charge of Civil Service