Pythagoras and the Delphic Mysteries by Edouard Schure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Echo of Delphi: the Pythian Games Ancient and Modern Steven Armstrong, F.R.C., M.A

An Echo of Delphi: The Pythian Games Ancient and Modern Steven Armstrong, F.R.C., M.A. erhaps less well known than today’s to Northern India, and from Rus’ to Egypt, Olympics, the Pythian Games at was that of kaloi k’agathoi, the Beautiful and PDelphi, named after the slain Python the Good, certainly part of the tradition of Delphi and the Prophetesses, were a mani of Apollo. festation of the “the beautiful and the good,” a Essentially, since the Gods loved that hallmark of the Hellenistic spirituality which which was Good—and for the Athenians comes from the Mystery Schools. in particular, what was good was beautiful The Olympic Games, now held every —this maxim summed up Hellenic piety. It two years in alternating summer and winter was no great leap then to wish to present to versions, were the first and the best known the Gods every four years the best of what of the ancient Greek religious and cultural human beings could offer—in the arts, festivals known as the Pan-Hellenic Games. and in athletics. When these were coupled In all, there were four major celebrations, together with their religious rites, the three which followed one another in succession. lifted up the human body, soul, and spirit, That is the reason for the four year cycle of and through the microcosm of humanity, the Olympics, observed since the restoration the whole cosmos, to be Divinized. The of the Olympics in 1859. teachings of the Mystery Schools were played out on the fields and in the theaters of the games. -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

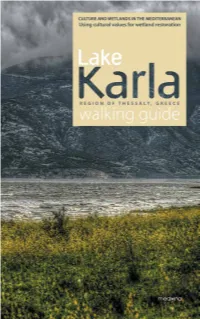

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research -

Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece

Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece SUSAN E. ALOCOCK JOHN F. CHERRY JAS ELSNER, Editors OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Pausanias pausanias Travel and Memory in Roman Greece Edited by Susan E. Alcock, John F. Cherry, & Jas´Elsner 3 2001 1 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota´ Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Saˆo Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright ᭧ 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pausanias : travel and memory in Roman Greece / edited by S.E. Alcock, J.F. Cherry & J. Elsner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-512816-8 (cloth) 1. Pausanias. Description of Greece. 2. Greece—Description and travel—Early works to 1800. 3. Greece—Antiquities. 4. Greece—Historiography. I. Alcock, Susan E. II. Cherry, John F. III. Elsner, Jas´. DF27.P383 P38 2000 938'.09—dc21 00-022461 Frontispiece: Location of principal places mentioned in the book. 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Silvia, Britten, and Bax This page intentionally left blank Preface This volume is dedicated to the principle that Pausanias deserves more—and more ambitious—treatment than he tends to receive. -

Optitrans Baseline Study Thessaly

OPTITRANS BASELINE STUDY THESSALY Version 1.0 Date: February 2019 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2 Population and Territorial Characteristics ............................................................................................. 6 2.1 Regional Unit of Larissa ................................................................................................................. 9 2.2 Regional Unit of Trikala ................................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Regional Unit of Karditsa .............................................................................................................. 11 2.4 Regional Unit of Magnesia ........................................................................................................... 12 2.5 Regional Unit of Sporades ........................................................................................................... 13 3 Mobility and Transport Infrastructure ................................................................................................... 14 3.1 Road Transport ............................................................................................................................. 14 3.2 Rail Transport ............................................................................................................................... 17 3.3 Sea Transport .............................................................................................................................. -

Thermopylae 480 BC: Leonidas Last Stand Ebook Free Download

THERMOPYLAE 480 BC: LEONIDAS LAST STAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nic Fields,Steve Noon | 96 pages | 20 Nov 2007 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781841761800 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom Thermopylae 480 BC: Leonidas Last Stand PDF Book Aug 09, Bob Mask rated it it was amazing. For you, inhabitants of wide-wayed Sparta, Either your great and glorious city must be wasted by Persian men, Or if not that, then the bound of Lacedaemon must mourn a dead king, from Heracles' line. Certainly, those who left on the third day did not think they had joined a suicide squad. Published November 20th by Osprey Publishing first published November 6th Also obedience in its highest form is not obedience to a constant and compulsory law, but a persuaded or voluntary yielded obedience to an issued command Matheus rated it it was amazing Mar 31, List of ancient Greeks. Aaron Ray rated it really liked it Nov 13, Stranger, report this word, we pray, to the Spartans, that lying Here in this spot we remain, faithfully keeping their laws. Although these many city-states vied with one another for control of land and resources, they also banded together to defend themselves from foreign invasion. The Ionian revolt threatened the integrity of his empire, and Darius thus vowed to punish those involved, especially the Athenians, "since he was sure that [the Ionians] would not go unpunished for their rebellion". He began the same way his predecessor had: he sent heralds to Greek cities—but he skipped over Athens and Sparta because of their previous responses. -

Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania, &C

W M'f-ff sA* JOURNALS OT \ LANDSCAPE PAINTER IN ALBANIA. &c BY EDWARD LEAR A A \ w LONDON: RICHARD BENTLEY. $u&Its!)ct fu ©rtjfnavo to %]n fHajesttr. 01 • I don: Printci clnilze and Co., 13, Poland Street. LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. MAP To face YENinjK VODHEXA MO.V A STIR A KM Rill II A TYRANA KROIA sk<5dra DURAZZO BERAT KHIMARA AVLONA TEPELKNT ARGHYROKASTRO IOANNIXA NICOPOLIS ART A SULI PARGA METEOR A TKMPE INTRODUCTION. The following Notes were written during two journeys through part of Turkey in Europe:—the first, from Saloniki in a north-western direction through ancient Macedonia, to Illyrian Albania, and by the western coast through Epirus to the northern boundary of modern Greece at the Gulf of Arta : —the second, in Epirus and Thessaly. Since the days of Gibbon, who wrote of Albania, — "a country within sight of Italy less known than the interior of America,"— much has been done for the topography of these and those who wish for a clear regions ; insight into their ancient and modern defini- tions, are referred to the authors who, in the present century, have so admirably investigated and so admirably illustrated the subject. For neither the ability of the writer of these B 1 2 l\ I R0D1 i 1 1 of journals, nor their -cope, permil an) attempt to follow in track of those on his pari the learned travellers: enough if he may avail himself of their Labours by quotation where such aid is necessary throughout his memo- randa <»!' an artist's mere tour of search among the riches of far-away Landscape. -

Myths and Legends: Apollo Loves Daphne, but She Doesn't Love Him Back by James Baldwin on 02.21.17 Word Count 1,035

Myths and Legends: Apollo loves Daphne, but she doesn't love him back By James Baldwin on 02.21.17 Word Count 1,035 Apollo (right) and Daphne as painted by Francesco Albani who lived from 1578 to 1660. Wikimedia Commons Greek mythology evolved thousands of years ago. There was a need to explain natural events, disasters and events in history. Myths were created about gods and goddesses that had supernatural powers, human traits and human emotions. These ideas were passed down in beliefs and stories. Around 800 to 700 B.C., they were written in epic poems that described real wars, real disasters and the supernatural lives of the 12 main gods and goddesses on Mount Olympus in Greece. Lesser gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, and monsters are also part of Greek mythology. In a beautiful palace, far up on Mount Olympus, lived Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty, and her pretty little boy, Eros. Eros was a bright and winning little fellow; but since the truth must be told, he was mischievous, and often did harm by his thoughtless ways. His mother had given him a bow and arrows, and Eros had become quite a skillful archer. Sometimes, however, he sent his arrows so carelessly that he wounded people without meaning to do so. The arrows were tiny, but the wounds they made were difficult to heal. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. 1 One day Eros sat on the rim of a fountain, shooting at the pond lilies, which seemed to be glancing up at him and filling the air with dainty perfume. -

Homer's Great Epic Poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, Composed

GODS AND HUMANS I. GODS AND HUMANS: THE NEW CONTRACT WITH NATURE Homer’s great epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, reverse was true in the case of its principal festival, composed probably in the eighth century B.C.E., reveal the Panathenaia, these processions took the people to us a confident civilization of youthful promise, at from the city into the exurban landscape, where many a time when it was fashioning for itself a glorious nar- of the important religious sanctuaries were located, rative of its history as a diverse but culturally united thereby affirming the territorial dominance of the people. Valor in war, accomplished horsemanship, and polis over its surrounding agrarian countryside. These the consoling power of a well-developed sense of ritual festivals held in nature also served as initiatory beauty are intrinsic to this worldview. The worship of rites for adolescents as they became participants in trees and aniconic stones—nonrepresentational, non- civic life. In ancient Sparta, where the city-state played symbolical forms—had been superseded by the per- an especially strong role in the education of children sonification of divinity. Although the powers and and adolescents, the festivals were connected with the personalities of the gods and goddesses were still in worship of Artemis Orthia. the process of formation, it is clear that they popu- The increasing power of the aristocracy spurred lated the collective imagination not as representatives the creation of the arts and the organization of ath- of an ethical system or figures commanding wor- letic competitions. The festivals were characterized shipful love, but rather as projections of the human by communal procession and sacrifice performed psyche and personifications of various aspects of before the sanctuaries of the gods, as well as by danc- human life. -

Ritual Death in Harry Crews's the Gospel Singer Anne FOATA

From: The Southern Quaterly, vol. 39, no. 4, 2001, p. 58-62. Tragedy on the road to Enigma: Ritual death in Harry Crews’s The Gospel Singer Anne FOATA Universit´eMarc Bloch, Strasbourg, France Just as Dionysus is he who devours and is devoured, so Apollo is he who pursues and flees. Viewed from the panoramic vantage afforded by thirty odd years of novel writing, Harry Crews’s violent, macabre, often farcical world of grotesques is apt to convey an unsettling impression of sameness. Unsettling, that is, for the writer of the present article, a dedicated reader of Crews’s novels, who might appear not to do justice to the enormous variety of characters in his fiction and, hence, to his sustaining ability to create life-like, albeit extreme, people and situations. But sameness all the same, if one may say so, to the extent that any one of Crews’s characters is prey to an obsession; and who of all people can be more monochord, monobasic, and let’s say it, monotonous than a monomaniac? Karatekas, bodybuilders and beauty queens share the same obsessive worship of perfection, car freaks consume their vehicles in manic communion, compulsive sinners hanker after salvation. Most of Crews’s males lust after female flesh and about all of his characters long to be somewhere else, far from their ordinary lives and ordinary selves, in a frenzied, misdirected search for meaning. Thus, Crews’s grotesque Southern landscape may appear as the land- scape of modern man’s soul set adrift in a world deprived of the old Chris- tian certainties and prey to untrammeled desires of every kind. -

The Lower Palaeolithic Record of Greece

The Early and Middle Pleistocene archaeological record of Greece : current status and future prospects Tourloukis, V. Citation Tourloukis, V. (2010, November 17). The Early and Middle Pleistocene archaeological record of Greece : current status and future prospects. LUP Dissertations. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16150 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16150 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 4 – The Lower Palaeolithic record of Greece 4.1 INTRODUCTION (WITH A SHORT lished renders any re-evaluation considerably diffi- REFERENCE TO THE MIDDLE cult (e.g. Andreikos 1993; Sarantea 1996). In those PALAEOLITHIC) cases, either the artefactual character of the finds or the chronological attribution to the Lower Palaeo- Unambiguous lithic evidence or human remains dat- lithic has already been disputed (e.g. see Runnels ing to the Early and early Middle Pleistocene are so 1995, 708, and Papagianni 2000, 9 for a critique of far lacking in Greece. Lithic material that is consid- the two examples of publications cited above). ered to date to the (late) Middle Pleistocene is scarce and mostly consists of finds that have been chronolo- Meager as the record is, the fact remains that indica- gically bracketed only in the broadest of terms, with tions for the presence of humans already from the relative dating techniques that are mainly based on late Middle Pleistocene have been reported from the inferred archaic morphology of the artefacts and areas that are spread over almost the entire country on usually inadequate stratigraphic correlations. -

WITH the GODS on MOUNT OLYMPUS by Aristides E

WITH THE GODS ON MOUNT OLYMPUS By Aristides E. Phoutrides and Francis P. Farquhar ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHORS Olympus—hark !—and Kissavos, the brother mountains quarrel. Which of the two shall throw the rain, and which shall throw the snow; And Kissavos does throw the rain; the snow, that throws Olympus. To Kissavos Olympus turns and speaks to him with anger: "Chide me not, Kissavos, Turk-trodden, shameless mountain! On thee a faithless breed, Larissa's Turks are trampling; Oljonpus am I! Great of yore, and in the world renowned! My peaks are forty-two, my fountains two and sixty; On every peak there flies a flag, 'neath every branch rest Klephtes; And yearly, when the springtime comes, and when the young twigs blossom. My warring Klephtes cUmb my peaks—the slaves may fill my valleys. Mine is the golden eagle, too, the bird of golden pinions,— Look!—perched on the cliff he stands and with the sun converses: 'Sun mine, why from the early morn sendest thou not thy sunbeams? Strike with thy Ught! Why must I wait tiU noon to warm my talons?'" —Translation of a folk-song known all over Greece, and sung in every country district, whether in Thessaly or Macedonia, or in Central Hellas or the Peloponnesus. SNY one travelling across mountain kings battle against each other. the plain of Thessaly It was this spectacle that suggested to the in the vicinity of Larissa ancient Greeks the world-war between cannot help being im the Olympian gods and the Titans of pressed with the sharp Ossa; and to their modern descendants contrast between the two the strife of an animate Olympus with mountains that rise in the northeast.