Museums and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nail Salon Owner Is on a Quest to Help Ex-Felons

Public Records & Notices Monitoring local real estate since 1968 View a complete day’s public records Subscribe Presented by and notices today for our at memphisdailynews.com. free report www.chandlerreports.com Tuesday, April 20, 2021 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 136 | No. 47 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Whitehaven school’s ‘store’ rewards positive behavior DAJA E. HENRY bags of chips and basketballs to fourth-grader Jeremiah Haynes the Trailblazer Incentive Store is is a big deal to Phi Beta Sigma,” Courtesy of The Daily Memphian hoverboards and bicycles. said. The initiative started off as packed with prizes. said Dwayne Scott, chair of the Behind a royal blue ribbon and Third grader Maleek McClin- a cart stocked with candy that The goodies are for students chapter’s foundation. “We’re com- a closed door emblazoned with the ton broke out in dance, showing teachers would push around to who model positive behavior and mitted to you as long as Tau Iota school’s logo, students at Robert R. what he would do once he earned incentivize positive behavior. respect, excel in the classroom, Sigma is around. ... We are defi- Church Thursday, April 15, got to enough points for a BeyBlade. Now, after a $10,000 donation have good attendance or any nitely happy to labor with you and see for the first time a new incen- “I’m a gamer so I might as well from the Tau Iota Sigma chapter other behavior that would build tive store with prizes ranging from get a PlayStation 4 and AirPods,” of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity Inc., up their ClassDojo points. -

Reference # Resource Name Address County City Listed Date Multiple

Reference # Resource Name Address County City Listed Date Multiple Name 76001760 Arnwine Cabin TN 61 Anderson Norris 19760316 92000411 Bear Creek Road Checking Station Jct. of S. Illinois Ave. and Bear Creek Rd. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS 92000410 Bethel Valley Road Checking Station Jct. of Bethel Valley and Scarboro Rds. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS 91001108 Brannon, Luther, House 151 Oak Ridge Tpk. Anderson Oak Ridge 19910905 Oak Ridge MPS 03000697 Briceville Community Church and Cemetery TN 116 Anderson Briceville 20030724 06000134 Cross Mountain Miners' Circle Circle Cemetery Ln. Anderson Briceville 20060315 10000936 Daugherty Furniture Building 307 N Main St Anderson Clinton 20101129 Rocky Top (formerly Lake 75001726 Edwards‐‐Fowler House 3.5 mi. S of Lake City on Dutch Valley Rd. Anderson 19750529 City) Rocky Top (formerly Lake 11000830 Fort Anderson on Militia Hill Vowell Mountain Rd. Anderson 20111121 City) Rocky Top (formerly Lake 04001459 Fraterville Miners' Circle Cemetery Leach Cemetery Ln. Anderson 20050105 City) 92000407 Freels Cabin Freels Bend Rd. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS Old Edgemoor Rd. between Bethel Valley Rd. and Melton Hill 91001107 Jones, J. B., House Anderson Oak Ridge 19910905 Oak Ridge MPS Lake 05001218 McAdoo, Green, School 101 School St. Anderson Clinton 20051108 Rocky Top (formerly Lake 14000446 Norris Dam State Park Rustic Cabins Historic District 125 Village Green Cir. Anderson 20140725 City) 75001727 Norris District Town of Norris on U.S. 441 Anderson Norris 19750710 Tennessee Valley Authority Hydroelectric 16000165 Norris Hydrolectric Project 300 Powerhouse Way Anderson Norris 20160412 System, 1933‐1979 MPS Roughly bounded by East Dr., W. -

John Chavis: Incredible W&L Alum

John Chavis: Incredible W&L Alum Court Nexsen May 10, 2006 Anth. 403 Professor Galke Washington & Lee University •- Ar, ~~· · u ~µology Laboratory Reverend John Chavis was a man of strong moral character who achieved great academic success and lived as a free Negro during the late 18th to early 19th century. Born in Granville County, North Carolina in 1763, Chavis was a deeply religious man who possessed a love for rhetoric and the classics. As a Presbyterian minister he opened a school in Raleigh, North Carolina where he taught both white and black children. Such notable pupils were native No1ih Carolina Whig, Senator Willie P. Magnum, North Carolina Governor Charles Manly, and New Mexico Governor Abram Rencher. During a time ofracial tension, Chavis managed to gain the trust of white families, instruct their children, preach in their churches, and visit their homes. A famous and prominent free man of color, Jolm Chavis was regarded as a man of unquestionably good fame and exemplary piety who was arguably one of the most important and influential characters of his time. Both historians and the black community recognize the achievements and outstanding life ofChavis, but Washington and Lee University, where Chavis once studied, does not. John Chavis was Washington and Lee University's first African-American student, yet the school has done very little to publicize this significant piece of history. Chavis came to Lexington in 1795, at the time the school was still Liberty Hall Academy, and prior to his arrival he had been privately tutored by Dr. John Witherspoon at the College ofNew Jersey, now Princeton University. -

A Directory of Tennessee Agencies

Directory of Tennessee Agencies Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum African American Heritage Society Lincoln Memorial University McLemore House Museum Cumberland Gap Parkway P. O. Box 2006 P.O. Box 17684 Harrogate, TN 37752-2006 Nashville, TN 37217 423-869-6235 Acuff-Ecoff Family Archives African American Historical & P. O. Box 6764 Genealogical Society Knoxville, TN 37914-0764 Tennessee Chapter, AAHGS 865-397-6939 Nutbush, TN 38063 731-514-0130 Adams Museum African Roots Museum Bell School Building 12704 Highway 19 7617 Highway 41N Mary Mills Adams, TN 37010 1777 West Main Street Franklin, TN 37064 615-794-2270 Adventure Science Center Alex Haley House Museum THC 800 Fort Negley Boulevard Alex Haley Museum Association Nashville, TN 37203 200 S. Church Street 615-862-5160 P. O. Box 500 Henning, TN 38041 731-738-2240 African American Community Allandale Committee and Information Center Friends of Allandale/City of Kingsport Connie Baker 4444 West Stone Drive P.O. Box 455 Kingsport, TN 37660 Elizabethton, TN 37643 423-229-9422 423-542-8813 African American Cultural Alliance American Association for State and P.O. Box 22173 Local History Nashville, TN 37202 1717 Church Street 615-329-3540 Nashville, TN 37203-2991 615-230-3203 African American Genealogical and American Baptist College Historical Society T. L. Holcomb Library Dr. Tommie Morton Young 1800 Baptist World Center Drive P.O. Box 281613 Nashville, TN 37207 Nashville, TN 37228 615-687-6904 615-299-5626 Friday, October 13, 2006 Page 1 of 70 American Legion Anubis Society Department of Tennessee 1816 Oak Hill Drive 215 8th Avenue North Kingston, TN 37763 Nashville, TN 37203 615-254-0568 American Museum of Science & Energy Appalachian Caverns Foundation 300 South Tulane Ave. -

Chavis Hall 1763–1838

JOHN ChavisChavis Hall 1763–1838 f “Without any exception the most remarkable black man who ever lived in the United States.” —joseph lacy seawell 1924 New York Times Magazine “Prejudice...blinds the mind and forbids free and open investigation after truth.” –John Chavis Chavis Hall d john chavis was an alumnus of washington and lee and the first african-american known to receive a college education in the united states. Born in 1763 in North Carolina, Chavis was a Revolutionary War soldier. In 1792, he began studying for the ministry at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Chavis moved to Virginia in 1795 and completed his studies at Washington Academy (now Washington and Lee University). He was licensed to preach by the Lexington Presbytery in 1800 and became a circuit-riding missionary. By 1809, Chavis had settled in Raleigh, North Carolina, and, in addition to preaching, had opened a school in his home where he taught both black and white students, including several prominent North Carolinians. Chavis died in 1838. ChavisJOHN 1763–1838 f ohn Chavis was born a free black in 1763 in North Carolina. He enlisted in 1778 as a soldier in the J Revolutionary War, serving three years in the 5th Virginia Regiment. Although there are few records that document his early life, Chavis’s name appears on the roster of Virginia Soldiers of the American Revolution. His home is listed as Mecklenburg, Virginia. To supplement his income as a circuit rider, Chavis opened a school in his home near Raleigh, North Carolina, where he taught both white and black children. -

Memphis 2018 - 50 Years Since MLK

THE MAGAZINE OF MEMPHIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL | SPRING 2015 Harvesting Fun and Games at Shelby Farms Celebrating 150 Years of Toof Printing Breaking the Record for Downhill Biking Coaching and Ministering on the Gridiron FLIGHT SURGEON Charles Frankum ’86 Pilots Mile-High Medical Practice Bridge to Somewhere Cross the 200-foot, steel-truss bridge from the Wolf River Greenway and enter the many habitats of Shelby Farms Park – forests and water features, paved and primitive trails, an expansive dog park and fanciful children’s playground, even a buffalo herd. The Heart of the Park Enhancement, expected to be complete in 2016, is creating a new centerpiece for the 4,500-acre Mid-South treasure. Read about the improvements and how alumni have contributed to the vision, financing, and construction of one of the largest urban parks in the country on page 8. MUS TODAY contents Memphis University School Founded 1893 FEATURES Surgeon Commutes to Patients via Plane MISSION STATEMENT 4 Memphis University School is a college- Shelby Farms Supporters Create Park for the Ages preparatory school dedicated to academic 8 excellence, cultivation of service and leadership, and the development of Alumni Reflect on 150 Years of Toof Printing well-rounded young men of strong moral 14 character, consistent with the school’s Air Force Commandant Takes on New Role Christian tradition. 18 HEADMASTER Downhill Biker Sets U.S. Record at Age 67 Ellis L. Haguewood 20 Earth to Echo Writer Speaks with Film Students BOARD OF TRUSTEES 22 Samuel N. Graham II ’80, Chairman Gary K. Wunderlich, Jr. ’88, Faith-Based Group Offers Legal Counsel with Heart Vice Chairman 24 D. -

Judge Grants DNA Testing in 1987 Murder Case

Public Records & Notices Monitoring local real estate since 1968 View a complete day’s public records Subscribe Presented by and notices today for our at memphisdailynews.com. free report www.chandlerreports.com Friday, September 18, 2020 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 135 | No. 127 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Empty chairs, stage demonstrate problems for live-events industry TOM BAILEY a stage dotted the vast, riverside celebrations, concerts and other led the local part of a national, the 6-month-old Live Events Courtesy of The Daily Memphian lawn Tuesday afternoon, Sept. face-to-face activities for crowds. “Empty Event” effort. Coalition. Those strolling through Tom 15.The answer: No one. That means the 12 million peo- Similar “Empty Event” dis- The purpose of the “Empty Lee Park might have wondered Which was the point of “Emp- ple who earn a living setting up plays have happened or are Event” spectacles is not only to who would be hosting the fancy ty Event,” a combination of stage events, securing them, entertain- planned in New York City, Wash- bring attention to how COV- outdoor event. Forty-eight ta- craft, pop-up public art and press ing for them and decorating them ington, D.C., Boston, San Di- ID-19 has crushed the live-events bles with centerpieces and table conference. Practically no one are struggling to find work. ego, Texas, Kentucky and Den- clothes, 384 seats, two bars and is staging business meetings, Memphis-based LEO Events ver, all under the umbrella of EMPTY CONTINUED ON P2 DNA testing of crime scene evidence that includes a knife used in the murders, eyeglasses, and blood- Judge grants DNA testing in stained items such as a washcloth, clothing of Payne and the victims, curtains, a rug, stuffed animals and a tampon. -

Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936

Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936 Processed by Cameron Sandlin, Lily Flores, and Max Farley 2017 Memphis and Shelby County Room Memphis Public Library and Information Center 3030 Poplar Ave Memphis, TN 38111 Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936 2 Memphis Police Department Homicide Reports 1917-1936 Memphis Police Department Historical Sketch The history of police activity in Memphis began in 1827 with the election of John J. Balch. Holding the title of town constable, the “one-man Police Department” also worked as a tinker and patrolled on foot an area of less than a half square mile in the young town of Memphis.1 As the river town expanded and developed a rough reputation throughout the 1830’s, the department remained small, first experiencing growth in 1840 when the force expanded to include the Night Guard, a night-shift force of watchmen. In 1848, the town of Memphis became the city of Memphis. During that same year, the elected office of City Marshal replaced the position of town constable, and the duties of the office expanded to include “duties related to sanitation, zoning, street maintenance,” in addition to policing the newly-minted city.2 In 1850, the total police force numbered 26 men, split between the Day Squad and the Night Squad, and by 1860, a police force with a structure that could be characterized as modern was in place in Memphis, with the position of Chief of Police clearly stated in city ordinances as the leader of the police force. Following the Civil War, the Memphis Police Department (MPD) expanded to manage the rapidly growing Bluff City. -

Class of 2014 Leaves a Legacy Kayla Williamson of This Year’S Seniors

The Eagle’s Eye Senior Edition St. Benedict at Auburndale he agle’s Mayye 2013 1 T Volume 10 Issue 6 E St. Benedict at Auburndale High School,E Cordova, TN May 5, 2014 Senior Edition photos by Sharon Masterson The Class of 2014 screams, shouts, and cheers for the Eagles as they try to win the spirit stick at a pep rally during their freshman year (left) and their senior year (right). Class of 2014 leaves a legacy Kayla Williamson of this year’s seniors. Enroll- of West Side Story, both re- astounding amounts of ef- sports a unique pair of cat-eye Copy Editor ment for senior honors and cently received nominations fort towards school projects, glasses. The Class of 2014 re- AP classes is particularly high, for “Outstanding Technical volunteer efforts, and other alized that a real queen should It’s 2010. The gym’s bleach- and college acceptances range Achievement” at the 2014 community service organiza- not be chosen based on her ex- ers are packed and fit to burst. anywhere from California to High School Musical Theatre tions. The senior project raised terior beauty, but rather by her Mr. Bilbrey’s voice booms Paris, including several high- Awards, hosted by the Or- around $3,000 for Habitat for authenticity and the warmth over the loudspeaker, daring level institutions like Tufts pheum. The school-renowned Humanity, and the seniors of her heart. Therefore, they students to out-scream each University and the University band Half Dollar Tonic, which won the class competition chose Lucy as queen, and Lucy other for the coveted spirit of Notre Dame. -

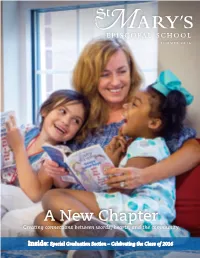

A New Chapter Creating Connections Between Words, Hearts, and the Community

SUMMER 2016 A New Chapter Creating connections between words, hearts, and the community Inside: Special Graduation Section – Celebrating the Class of 2016 S t. Mary’s girls love words. From the moment you walk in the doors of the school, girls of all ages are embracing words. They love to use them correctly, to play with them, and to learn new ones. I discovered this logophilia – the love of words, and word games – quickly when I first joined the St. Mary’s community in 2004. Their care for words extended from a note by a candy bowl to exquisitely written college essays. The success of Student Council campaigns seems to depend on the apt turn of phrase on the banners. And where else but at St. Mary’s does the Middle School Halloween costume winner owe her victory to creating the best visual pun? One English teacher stated this affection more boldly, “Our students leave St. Mary’s as the defenders of the English Language.” At the heart of academic success is learning to read. At St. Mary’s, we delight in teaching students of all ages the art of engaged reading. In the stories that follow, you will see how St. Mary’s is continuing its strong tradition in developing learners and creating more opportunities for our girls and for children across Memphis to discover their love of words. The Nathaniel C. Hughes Learning Center is our most recent accomplishment in fostering life-long learning. It is only fitting that Dr. Hughes’ name is honored through this center; an esteemed scholar and former headmaster, he raised St. -

January 2017 ◊ a Monthly Newsletter for and by the Members of MAGS Mapping Prehistoric Tool-Stone Use in This Issue Ryan M Parish, Ph

MEMPHIS ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY MAGS Rockhound News ◊ A monthly newsletter for and by the members of MAGS Volume 63 ! Number 01 ! January 2017 ! A monthly newsletter for and by the members of MAGS Mapping Prehistoric Tool-stone Use In this issue Ryan M Parish, Ph. D.!!!January Program Mapping Prehistoric Department of Earth Sciences, The University of Memphis Tool-stone Use" P. 1 Public Comment" P. 1 MAGS And Federation Notes"" P. 2 President’s Message" P. 3 Acclaim for Your Newsletter"" P. 3 Library Report"" P. 4 January Birthdays" P. 4 Attention MAGS Members P. 5 Fabulous Tennessee Fossils P. 5 New Members"" P. 6 Richardson Landing Finds P. 6 November Board Minutes P. 6 November Meeting Minutes P.7 MAGS17 Membership Programs"" P. 7 Celebration"" P. 7 Ferdinand Braun… The focus of my talk will be (to date consisting of close to Modern World" P. 8 understanding prehistoric behav- 5,000 samples from approximately What An Adventure!" P. 9 ior from understanding where on 170 deposits), 2) sourcing chert Jewelry Bench Tips" P. 11 the landscape they obtained chert artifacts back to the location on Dino History Revised" P. 11 to use for manufacturing stone the landscape where people got tools. I'd like to briefly summar- the resource, and 3) I'll wrap MAGS At A Glance" P. 12 ize: 1) my work on creating a chert things up with some of the recent type database for the Southeast groups of artifacts Continued, P. 5 PUBLIC COMMENTS"LINDA MCCALL, PRESIDENT, NORTH CAROLINA FOSSIL CLUB The Paleontological Resources Protection Act The next paragraph is an announcement from (PRPA) was signed into law on 30 March 2009, and Scott Foss of the BLM and Vincent Santucci of the federal agencies were tasked with writing their own National Park Service. -

SBA Welcomes New Principal Amanda Slade Scription Can Merit; Every Day Tennis; She Even Started SBA’S Co-Editor Brings Unique and Different Ex- Cross Country Team

he agle’s ye TVolume 10 Issue 1 ESt. Benedict at Auburndale High School, ECordova, TN October 3, 2013 SBA welcomes new principal Amanda Slade scription can merit; every day tennis; she even started SBA’s Co-Editor brings unique and different ex- cross country team. periences. Outside of school, Mrs. Mor- Sondra Morris, a long-time “When we were getting new ris is the mother of five chil- SBA faculty member, crowns bleachers over the summer, dren, including Clare, an SBA her 28th year with one of the I learned about construction. junior. most notable positions—prin- I even learned the difference “[Having my mom as prin- cipal. between a good concrete pour cipal] has its ups and downs. Following the departure of and a bad concrete pour,” said Overall, it’s nice [to have her former principal George Va- Mrs. Morris. here] when I forget things,” ladie, the Superintendent and As principal, she also “rep- said Clare. the Bishop asked Mrs. Morris resents SBA off-campus,” like She is married to the Director if she would take on the role when attending meetings and of Marketing and Communica- of interim principal. when students receive outside tions of SBA’s rival, CBHS. “Mr. Valadie was a fabulous awards, such as “Best of the However, even though the two leader and visionary. I’m go- Preps” and “Academic All- schools exist in harmony in ing to have to be at the top Stars.” the Morris home, she knows of my game,” she said. “[My During her years at SBA, where to draw the line.