X-Ray Optics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polarization of Light: Malus' Law, the Fresnel Equations, and Optical Activity

Polarization of light: Malus' law, the Fresnel equations, and optical activity. PHYS 3330: Experiments in Optics Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 (Dated: Revised August 2012) In this lab you will (1) test Malus' law for the transmission of light through crossed polarizers; (2) test the Fresnel equations describing the reflection of polarized light from optical interfaces, and (3) using polarimetry to determine the unknown concentration of a sucrose and water solution. I. POLARIZATION III. PROCEDURE You will need to complete some background reading 1. Position the fixed \V" polarizer after mirror \M" before your first meeting for this lab. Please carefully to establish a vertical polarization axis for the laser study the following sections of the \Newport Projects in light. Optics" document (found in the \Reference Materials" 2. Carefully adjust the position of the photodiode so section of the course website): 0.5 \Polarization" Also the laser beam falls entirely within the central dark read chapter 6 of your text \Physics of Light and Optics," square. by Peatross and Ware. Your pre-lab quiz cover concepts presented in these materials AND in the body of this 3. Plug the photodiode into the bench top voltmeter write-up. Don't worry about memorizing equations { the and observe the voltage { it should be below 200 quiz should be elementary IF you read these materials mV; if not, you may need to attenuate the light by carefully. Please note that \taking a quick look at" these [anticipating the validity off Malus' law!] inserting materials 5 minutes before lab begins will likely NOT be the polarizer on a rotatable arm \R" upstream of adequate to do well on the quiz. -

Lecture 26 – Propagation of Light Spring 2013 Semester Matthew Jones Midterm Exam

Physics 42200 Waves & Oscillations Lecture 26 – Propagation of Light Spring 2013 Semester Matthew Jones Midterm Exam Almost all grades have been uploaded to http://chip.physics.purdue.edu/public/422/spring2013/ These grades have not been adjusted Exam questions and solutions are available on the Physics 42200 web page . Outline for the rest of the course • Polarization • Geometric Optics • Interference • Diffraction • Review Polarization by Partial Reflection • Continuity conditions for Maxwell’s Equations at the boundary between two materials • Different conditions for the components of or parallel or perpendicular to the surface. Polarization by Partial Reflection • Continuity of electric and magnetic fields were different depending on their orientation: – Perpendicular to surface = = – Parallel to surface = = perpendicular to − cos + cos − cos = cos + cos cos = • Solve for /: − = !" + !" • Solve for /: !" = !" + !" perpendicular to cos − cos cos = cos + cos cos = • Solve for /: − = !" + !" • Solve for /: !" = !" + !" Fresnel’s Equations • In most dielectric media, = and therefore # sin = = = = # sin • After some trigonometry… sin − tan − = − = sin + tan + ) , /, /01 2 ) 45/ 2 /01 2 * = - . + * = + * )+ /01 2+32* )+ /01 2+32* 45/ 2+62* For perpendicular and parallel to plane of incidence. Application of Fresnel’s Equations • Unpolarized light in air ( # = 1) is incident -

The Fresnel Equations and Brewster's Law

The Fresnel Equations and Brewster's Law Equipment Optical bench pivot, two 1 meter optical benches, green laser at 543.5 nm, 2 10cm diameter polarizers, rectangular polarizer, LX-02 photo-detector in optical mount, thick acrylic block, thick glass block, Phillips multimeter, laser mount, sunglasses. Purpose To investigate polarization by reflection. To understand and verify the Fresnel equations. To explore Brewster’s Law and find Brewster’s angle experimentally. To use Brewster’s law to find Brewster’s angle. To gain experience working with optical equipment. Theory Light is an electromagnetic wave, of which fundamental characteristics can be described in terms of the electric field intensity. For light traveling along the z-axis, this can be written as r r i(kz−ωt) E = E0e (1) r where E0 is a constant complex vector, and k and ω are the wave number and frequency respectively, with k = 2π / λ , (2) λ being the wavelength. The purpose of this lab is to explore the properties the electric field in (1) at the interface between two media with indices of refraction ni and nt . In general, there will be an incident, reflected and transmitted wave (figure 1), which in certain cases reduce to incident and reflected or incident and transmitted only. Recall that the angles of the transmitted and reflected beams are described by the law of reflection and Snell’s law. This however tells us nothing about the amplitudes of the reflected and transmitted Figure 1 electric fields. These latter properties are defined by the Fresnel equations, which we review below. -

Polarized Light 1

EE485 Introduction to Photonics Polarized Light 1. Matrix treatment of polarization 2. Reflection and refraction at dielectric interfaces (Fresnel equations) 3. Polarization phenomena and devices Reading: Pedrotti3, Chapter 14, Sec. 15.1-15.2, 15.4-15.6, 17.5, 23.1-23.5 Polarization of Light Polarization: Time trajectory of the end point of the electric field direction. Assume the light ray travels in +z-direction. At a particular instance, Ex ˆˆEExy y ikz() t x EEexx 0 ikz() ty EEeyy 0 iixxikz() t Ex[]ˆˆEe00xy y Ee e ikz() t E0e Lih Y. Lin 2 One Application: Creating 3-D Images Code left- and right-eye paths with orthogonal polarizations. K. Iizuka, “Welcome to the wonderful world of 3D,” OSA Optics and Photonics News, p. 41-47, Oct. 2006. Lih Y. Lin 3 Matrix Representation ― Jones Vectors Eeix E0x 0x E0 E iy 0 y Ee0 y Linearly polarized light y y 0 1 x E0 x E0 1 0 Ẽ and Ẽ must be in phase. y 0x 0y x cos E0 sin (Note: Jones vectors are normalized.) Lih Y. Lin 4 Jones Vector ― Circular Polarization Left circular polarization y x EEe it EA cos t At z = 0, compare xx0 with x it() EAsin tA ( cos( t / 2)) EEeyy 0 y 1 1 yxxy /2, 0, E00 EA Jones vector = 2 i y Right circular polarization 1 1 x Jones vector = 2 i Lih Y. Lin 5 Jones Vector ― Elliptical Polarization Special cases: Counter-clockwise rotation 1 A Jones vector = AB22 iB Clockwise rotation 1 A Jones vector = AB22 iB General case: Eeix A 0x A B22C E0 i y bei B iC Ee0 y Jones vector = 1 A A ABC222 B iC 2cosEE00xy tan 2 22 EE00xy Lih Y. -

Optical Modeling of Nanostructures

Optical modeling of nanostructures Phd Part A Report Emil Haldrup Eriksen 20103129 Supervisor: Peter Balling, Søren Peder Madsen January 2017 Department of Physics and Astronomy Aarhus University Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Maxwell’s Equations 5 2.1 Macroscopic form ................................. 5 2.2 The wave equation ................................ 6 2.3 Assumptions .................................... 7 2.4 Boundary conditions ............................... 7 2.5 Polarization conventions ............................. 7 3 Transfer Matrix Method(s) 9 3.1 Fresnel equations ................................. 9 3.2 The transfer matrix method ........................... 9 3.3 Incoherence .................................... 11 3.4 Implementation .................................. 14 4 The Finite Element Method 15 4.1 Basic principle(s) ................................. 15 4.2 Scattered field formulation ............................ 17 4.3 Boundary conditions ............................... 17 4.4 Probes ....................................... 19 4.5 Implementation .................................. 19 5 Results 20 5.1 Nanowrinkles ................................... 20 5.2 The two particle model .............................. 24 6 Conclusion 28 6.1 Outlook ....................................... 28 Bibliography 29 Front page illustration: Calculated field enhancement near a gold nanostar fabricated by EBL. The model geometry was constructed in 2D from a top view SEM image using edge detection and extruded to 3D. 1 Introduction Solar -

EXPERIMENT 3 Fresnel Reflection

EXPERIMENT 3 Fresnel Reflection 1. Reflectivity of polarized light The reflection of a polarized beam of light from a dielectric material such as air/glass was described by Augustin Jean Fresnel in 1823. While his derivation was based on an elastic theory of light waves, the same results are found with electromagnetic theory. The ratio of the reflected intensity to the incident intensity is called the reflectivity of the surface. It depends on the polarization of the incident light wave. Let be the angle of incidence and be the angle of transmission. Snell’s law relates these according to the refractive index in each media and : ( ) ( ) (1) The reflectivity for light polarized parallel to the plane of incidence (known as p-polarized light) is ( ) (2) ( ) but for light polarized perpendicular to the plane of incidence (known as s-polarized light) it is ( ) (3) ( ) Notice that for p-polarized light the denominator of the right hand side will be infinite when the sum ( ) . The angle of 1 incidence when this happens is called Brewster’s angle, . For light polarized in the plane of incidence, no energy is reflected at Brewster’s angle, i.e. 2. Making the measurements Getting started: A He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) beam is reflected from the front face of a prism on a rotating table. You can read the angle of rotation of the table from the precision index and vernier. It is very important to locate the center of the prism over the axis of rotation. Do this as best you can by eye. -

Foundations of Optics

Lecture 1: Foundations of Optics Outline 1 Electromagnetic Waves 2 Material Properties 3 Electromagnetic Waves Across Interfaces 4 Fresnel Equations Christoph U. Keller, Leiden University, [email protected] Lecture 1: Foundations of Optics 1 Electromagnetic Waves Electromagnetic Waves in Matter Maxwell’s equations ) electromagnetic waves optics: interaction of electromagnetic waves with matter as described by material equations polarization of electromagnetic waves are integral part of optics Maxwell’s Equations in Matter Symbols D~ electric displacement r · D~ = 4πρ ρ electric charge density ~ 1 @D~ 4π H magnetic field r × H~ − = ~j c @t c c speed of light in vacuum ~j electric current density 1 @B~ r × E~ + = 0 E~ electric field c @t B~ magnetic induction r · B~ = 0 t time Christoph U. Keller, Leiden University, [email protected] Lecture 1: Foundations of Optics 2 Linear Material Equations Symbols dielectric constant D~ = E~ µ magnetic permeability B~ = µH~ σ electrical conductivity ~j = σE~ Isotropic and Anisotropic Media isotropic media: and µ are scalars anisotropic media: and µ are tensors of rank 2 isotropy of medium broken by anisotropy of material itself (e.g. crystals) external fields (e.g. Kerr effect) mechanical deformation (e.g. stress birefringence) assumption of isotropy may depend on wavelength (e.g. CaF2 for semiconductor manufacturing) Christoph U. Keller, Leiden University, [email protected] Lecture 1: Foundations of Optics 3 Wave Equation in Matter static, homogeneous medium with no net charges: ρ = 0 for most materials: µ = 1 combine Maxwell, material equations ) differential equations for damped (vector) wave µ @2E~ 4πµσ @E~ r2E~ − − = 0 c2 @t2 c2 @t µ @2H~ 4πµσ @H~ r2H~ − − = 0 c2 @t2 c2 @t damping controlled by conductivity σ E~ and H~ are equivalent ) sufficient to consider E~ interaction with matter almost always through E~ but: at interfaces, boundary conditions for H~ are crucial Christoph U. -

3.3.3 Fresnel Equations Snell's Law Describes How the Angles Of

3.3.3 Fresnel equations Snell’s law describes how the angles of incidence and transmission are related through the refractive indices of the respective media. But what about the intensity of transmitted and reflected light? We are looking at a picture of the Montana glacier parks. White mountain tops are reflected in a perfectly still lake Mcdonald. It is a beautiful example of this video’s subject. Not only do we see the mountain tops reflected in the water, we can also find the each and every pebble lying on the bottom of the lake. A fraction of the light, reflected by the mountain tops, is reflected off the surface of the water. Another part is transmitted into the water and reflects off the rocks and pebbles. The Fresnel equations describe the intensity of the reflected and transmitted fractions. In this video we will learn which properties of light and matter affect the intensity of the transmitted and reflected light waves. We will introduce the concept of light polarization. Then we will discuss the fresnel equations and, finally, we will apply them to improve our solar cells. Let's look into the parameters that affect the fractions of light that are transmitted and reflected. This figure shows a light beam incident on the interface of two media. The refractive indices of both media, that describe how easily light propagates through a material, play an important role. The angle of incidence is also an important parameter. With the refractive indices and the angle of incidence we can calculate the angle of transmission, according to Snell’s law. -

Investigation of the Reflective Properties of a Left-Handed Metamaterial

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2007 Investigation of the Reflective Properties of a Left-Handed Metamaterial Amanda Durham Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Physics Commons Repository Citation Durham, Amanda, "Investigation of the Reflective Properties of a Left-Handed Metamaterial" (2007). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 92. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/92 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATION OF THE REFLECTIVE PROPERTIES OF A LEFT-HANDED METAMATERIAL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science By AMANDA DURHAM B.S., Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, 2004 2007 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES March 29, 2007 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Amanda Durham ENTITLED Investigation of the Reflective Properties of a Left-handed Metamaterial BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science. _______________________ Lok Lew Yan Voon, Ph.D. Thesis Advisor _______________________ Lok Lew Yan Voon, Ph.D. Department Chair Committee on Final Examination ____________________________ Lok Lew Yan Voon, Ph.D. ____________________________ Gregory Kozlowski, Ph.D. ____________________________ Douglas Petkie, Ph.D. ____________________________ Joseph F. Thomas, Jr., Ph.D. Dean, School of Graduate Studies Abstract Durham, Amanda, M.S., Department of Physics, Wright State University, 2007. -

A Study of Reflection and Transmission of Birefringent Retarders

JUST, Vol. IV, No. 1, 2016 Trent University A study of reflection and transmission of birefringent retarders James Godfrey Keywords Optics — Computational Physics — Theoretical Physics Champlain College 1. Interference in Rotating Waveplates The transmitted intensity of along each axis must be con- sidered separately, since equation (1-1) dictates that the re- 1.1 Research Goal flectance of the fast- and slow-axis components of the incident The objective of this project was to obtain a realistic theoreti- light will be different. The reflectance along the fast axis (Ro) cal prediction of the transmission curve for linearly-polarized and slow axis (Rs) are may be expressed: light incident normal on a [birefringent] retarder that behaves 2 as a Fabry-Perot etalon. The birefringent retarder considered n f − ni is a slab of birefringent crystal cut with the optic axis in the Ro = n f + ni face of the slab, and with parallel faces, and the waveplate has 2 no coating of any kind. ns − ni Rs = (1-2) Results of this project hoped to possibly explain the results ns + ni of work done by a previous student, Nolan Woodley, for his Physics project course in the 2013/14 academic year. In his Assuming the sides of the etalon are essentially paral- project, Woodley took many polarimeter scans which had a lel, the retarder may now be treated as a low-finesse (low- roughly sinusoidal shape [as they should], but adjacent peaks reflectance, R << 1) Fabry-Perot etalon. Their coefficients of of different heights. These differing heights were completely finesse (Fo and Fs, respectively) will also be different: unexplained, and not predicted by theory. -

13. Fresnel's Equations for Reflection and Transmission

13. Fresnel's Equations for Reflection and Transmission Incident, transmitted, and reflected beams Boundary conditions: tangential fields are continuous Reflection and transmission coefficients The "Fresnel Equations" Brewster's Angle Total internal reflection Power reflectance and transmittance Augustin Fresnel 1788-1827 Posing the problem What happens when light, propagating in a uniform medium, encounters a smooth interface which is the boundary of another medium (with a different refractive index)? k-vector of the incident light nincident boundary First we need to define some ntransmitted terminology. Definitions: Plane of Incidence and plane of the interface Plane of incidence (in this illustration, the yz plane) is the y plane that contains the incident x and reflected k-vectors. z Plane of the interface (y=0, the xz plane) is the plane that defines the interface between the two materials Definitions: “S” and “P” polarizations A key question: which way is the E-field pointing? There are two distinct possibilities. 1. “S” polarization is the perpendicular polarization, and it sticks up out of the plane of incidence I R y Here, the plane of incidence (z=0) is the x plane of the diagram. z The plane of the interface (y=0) T is perpendicular to this page. 2. “P” polarization is the parallel polarization, and it lies parallel to the plane of incidence. Definitions: “S” and “P” polarizations Note that this is a different use of the word “polarization” from the way we’ve used it earlier in this class. reflecting medium reflected light The amount of reflected (and transmitted) light is different for the two different incident polarizations. -

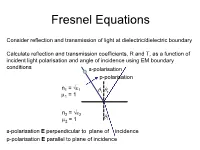

Fresnel Equations

Fresnel Equations Consider reflection and transmission of light at dielectric/dielectric boundary Calculate reflection and transmission coefficients, R and T, as a function of incident light polarisation and angle of incidence using EM boundary conditions s-polarisation p-polarisation n1 = √ε1 θ θ i r µ1 = 1 n = √ε 2 2 θ µ = 1 t 2 s-polarisation E perpendicular to plane of incidence p-polarisation E parallel to plane of incidence Fresnel Equations Snell’s Law Boundary conditions apply across the entire, flat interface (z = 0) Incident, reflected and transmitted waves are like i(ωt - kI.r) EI = (ey cosθi + ez sinθi) EoI e i(ωt - kR.r) ε kI ER = (-ey cosθr + ez sinθr) EoR e n1 = √ 1 θ θ i r kR i(ωt - kT.r) µ = 1 ET = (ey cosθt + ez sinθt) EoT e 1 y To satisfy BC (k . r) = (k . r) = (k . r) I z=0 R z=0 T z=0 ε n2 = √ 2 k (1) wave vectors lie in single plane z θt T µ2 = 1 (2) projection of wave vectors on xy plane is same From (1) θi = θr ω ω θ θ θ µ ε µ ε From (2) kI sin i = kR sin r = kT sin t kI = kR = c 1 1 kT = c 2 2 kI sin θi = kT sinθt becomes sin θi / sinθt = µ2ε2 / µ1ε1 Boundary conditions on E E fields at matter/vacuum interface d Boundary conditions on from Faraday’s Law d = .d E E. ℓ dt B S ∮퐶 − ∫푆 ∆t E.dℓ = EL.dℓL + ER.dℓR (as ∆t 0) ER ∮퐶 B.dS 0 (as ∆t → 0) dℓL θR ∫푆 → → θL θ θ dℓR -EL sin LdℓL + ER sin R dℓR = 0 EL EL sinθL = ER sinθR E||L = E||R E|| continuous Boundary conditions on H H fields at matter/vacuum interface Boundary conditions on H from Ampère’s Law ∇ x H = jfree + ∂D/∂t ∂D ∇ x H .dS = j + .dS = H.dℓ free ∂t �