Dienabou Barry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systemes Hydrauliques Du Delta Central Nigerien

SYSTEMES HYDRAULIQUES DU DELTA CENTRAL NIGERIEN NAMPALA ± SYSTEME LACUSTE '; MEMA 126 000 ha aménagéables 95 000 ha irrigables par gravité INTERVENTIONS DES BAILLEURS TIONGOBA (FED) KOKRY B (ARPON) RETAIL (AFD) M'BEWANI (KR2. BM. PAYS BAS. BOAD) KOKRY C (ARPON) RETAIL (AFD) s KOUMOUNA (BM) Molodo Nord (BOAD) GRUBER (ARPON) le E ab ité AK é av PLAINE AMONT (BSI) Molodo SUD (AFD; ACDI) KL/KO (ARPON; BSI) M ag gr RI n r OURO-NDIA A mé pa SERIBALA NORD (ARPON; BSI) NDILLA ( KFW) ALATONA (MCA) F a es '; ha bl 0 ga SOSSE-SIBILA (BM; ACDI) SABALIBOUGOU (BM) SOKOLO (BM) 00 rri 7 i 11 ha KOKRY A (ARPON) BOLONI ( KFW) TOURABA (UEMOA) 00 0 BOKY WERE (FED) N'DEBOUGOU 91 KE-MACINA (BOAD; OPEP. FK) SIENGO (BM; KFW; BID) TOGUERECOUMBE '; (8000 ha) ALATONA SINGO DIADIAN '; KOUROUMARI DIOURA 110 000 ha aménagéables '; ZONE DU KOUROUMARI 83 000 ha irrigables par gravité (8100 ha) KOKERI es té 148 000 ha aménagéables bl vi I éa ra SOKOLO R g r g ) 111 000 ha irrigables par gravité E a a '; a R n p h é A m s (9770 ha) 0 K a le 5 b 5 a a 3 h ( g BOSSITOMO 0 ri 0 ir (1270 ha)'; 0 a 5 h (1640 ha) 49 0 00 2 37 KANDIOUROU ! (2934 ha) ) a ) h C a T 0 h IN O 5 P 0 9 ( 8 5 1 MOLODO NORD ( KALA INFERIEUR 89 000 ha aménagéables MACINA 67 000 ha irrigables par gravité 776 000 ha aménagéables MOPTI N'DOBOUGOU '; ) CAMP 583 000 ha irrigables par gravité ) a h a '; TENENKOU ) h a 0 h 6 0 ) '; 4 a 0 5 h 0 7 4 0 ( 4 ZONE DE N'DEBOUGOU 4 5 3 ( SIENGO 7 2 ) 1 ha '; ( 0 25 KELESSERE (1 '; L’ Office du Niger en quelques dates DIA (1790 ha) 1919: Etude par l'ingénieur Bélime -

PROGRAMME ATPC Cartographie Des Interventions

PROGRAMME ATPC Cartographie des interventions Agouni !( Banikane !( TOMBOUCTOU Rharous ! Ber . !( Essakane Tin AÎcha !( Tombouctou !( Minkiri Madiakoye H! !( !( Tou!(cabangou !( Bintagoungou M'bouna Bourem-inaly !( !( Adarmalane Toya !( !( Aglal Raz-el-ma !( !( Hangabera !( Douekire GOUNDAM !( Garbakoira !( Gargando Dangha !( !( G!(ou!(ndam Sonima Doukouria Kaneye Tinguereguif Gari !( .! !( !( !( !( Kirchamba TOMBOUCTOU !( MAURITANIE Dire .! !( HaÏbongo DIRE !( Tonka Tindirma !( !( Sareyamou !( Daka Fifo Salakoira !( GOURMA-RHAROUS Kel Malha Banikane !( !( !( NIAFOUNKE Niafunke .! Soumpi Bambara Maoude !( !( Sarafere !( KoumaÏra !( Dianke I Lere !( Gogui !( !( Kormou-maraka !( N'gorkou !( N'gouma Inadiatafane Sah !( !( !( Ambiri !( Gathi-loumo !( Kirane !( Korientze Bafarara Youwarou !( Teichibe !( # YOUWAROU !( Kremis Guidi-sare !( Balle Koronga .! !( Diarra !( !( Diona !( !( Nioro Tougoune Rang Gueneibe Nampala !( Yerere Troungoumbe !( !( Ourosendegue !( !( !( !( Nioro Allahina !( Kikara .! Baniere !( Diaye Coura !( # !( Nara Dogo Diabigue !( Gavinane Guedebin!(e Korera Kore .! Bore Yelimane !( Kadiaba KadielGuetema!( !( !( !( Go!(ry Youri !( !( Fassoudebe Debere DOUENTZA !( .! !( !( !(Dallah Diongaga YELIMANE Boulal Boni !( !(Tambacara !( !( Takaba Bema # # NIORO !( # Kerena Dogofiry !( Dialloube !( !( Fanga # Dilly !( !( Kersignane !( Goumbou # KoubewelDouentza !( !( Aourou !( ## !( .! !( # K#onna Borko # # #!( !( Simbi Toguere-coumbe !( NARA !( Dogani Bere Koussane # !( !( # Dianwely-maounde # NIONO # Tongo To !( Groumera Dioura -

Région Cercles Commune

Sites affectés par le choléra en 2008 et 2011 Région Cercles Commune Ségou Niono Molodo Ségou Niono Niono Ségou Macina Macina Mopti Mopti Mopti Mopti Mopti Konna Mopti Mopti Dialloubé Mopti Mopti Borondougou Mopti Mopti Ouro mody Mopti Youwarou Dongo Mopti Youwarou N’Djodjiga Mopti Youwarou Farimaké Mopti Youwarou Deboye Zones de vulnérabilité WASH au Mali (risque d’inondation et d’épidémie de choléra) Page 1 Région Cercles Commune Mopti Youwarou Dirma Mopti Youwarou Youwarou Mopti Douentza Boré Mopti Djenné Kéwa Mopti Djenné Togué Mourari Mopti Bandiagara Timiniri Mopti Bandiagara Doucombo Mopti Tenenkou Ouro Ardo Kayes Diéma Diancoute Camara Kayes Kayes Kayes Kayes Kayes Bangassi Kayes Kayes Kéri Kaffo Kayes Kayes Kéméné Tambo Kayes Kayes Khouloum Kayes Kayes Samé Diomgoma Kayes Kayes Somankidy Kayes Kayes Sony Kayes Kayes Tafacirga Gao Bourem Bourem Tombouctou Tombouctou Tombouctou Tombouctou Diré Diré Tombouctou Gourma Rharous Gourma Rharous Tombouctou Niafunké Niafunké Tombouctou Goundam Goundam Kayes Kayes Sony Kayes Kayes Falémé Kayes Kayes Samè Kayes Kayes Diala Khasso Kayes Kayes Kayes N'di Kayes Kayes Liberté Dembaya Communes affectées par des inondations en 2010 et 2011 Région Cercle Commune Kidal Tessali Aguel Hoc Gao Gao Anchawadj Kayes Bafoulabé Bafoulabé Tombouctou Tombouctou Bambara Maoude Koulikoro Kati Bancoumana Mopti Bandiagara Bandiagara Sikasso Yanfolila Baya Tombouctou Tombouctou Ber Ségou Baraouli Boidiè Koulikoro Banamba Boron Gao Bourem Bourem Zones de vulnérabilité WASH au Mali (risque d’inondation et d’épidémie -

M650kv1906mlia1p-Mliadm22302-Koulikoro.Pdf (French (Français))

RÉGION DE KOULIKORO - MALI Map No: MLIADM22302 9°0'W 8°0'W 7°0'W 6°0'W M A U R I T A N I E ! ! ! Mo!ila Mantionga Hamd!allaye Guirel Bineou Niakate Sam!anko Diakoya ! Kassakare ! Garnen El Hassane ! Mborie ! ! Tint!ane ! Bague Guessery Ballé Mou! nta ! Bou!ras ! Koronga! Diakoya !Palaly Sar!era ! Tedouma Nbordat!i ! Guen!eibé ! Diontessegue Bassaka ! Kolal ! ! ! Our-Barka Liboize Idabouk ! Siramani Peulh Allahina ! ! ! Guimbatti Moneke Baniere Koré ! Chedem 1 ! 7 ! ! Tiap! ato Chegue Dankel Moussaweli Nara ! ! ! Bofo! nde Korera Koré ! Sekelo ! Dally ! Bamb!oyaha N'Dourba N 1 Boulal Hi!rte ! Tanganagaba ! S É G O U ! Djingodji N N ' Reke!rkaye ' To!le 0 Boulambougou Dilly Dembassala 0 ° ! ! ! ° 5 ! ! 5 1 Fogoty Goumbou 1 Boug!oufie Fero!bes ! Mouraka N A R A Fiah ! ! Dabaye Ourdo-Matia G!nigna-Diawara ! ! ! Kaw! ari ! Boudjiguire Ngalabougou ! ! Bourdiadie Groumera Dabaye Dembamare ! Torog! ome ! Tarbakaro ! Magnyambougou Dogofryba K12 ! Louady! Cherif ! Sokolo N'Tjib! ougou ! Warwassi ! Diabaly Guiré Ntomb!ougou ! Boro! dio Benco Moribougou ! ! Fallou ! Bangolo K A Y E S ! Diéma Sanabougou Dioumara ! ! ! Diag! ala Kamalendou!gou ! Guerigabougou ! Naou! lena N'Tomodo Kolo!mina Dianguirdé ! ! ! ! Mourdiah ! N'Tjibougou Kolonkoroba Bekelo Ouolo! koro ! Gomitra ! ! Douabougou ! Mpete Bolib! ana Koira Bougouni N16 ! Sira! do Madina-Kagoro ! ! N'Débougou Toumboula Sirao!uma Sanmana ! ! ! Dessela Djemene ! ! ! Werekéla N8 N'Gai Ntom! ono Diadiekabougou ! ! Dalibougou !Siribila ! ! Barassafe Molodo-Centre Niono Tiemabougou ! Sirado ! Tallan ! ! Begn!inga ! ! Dando! ugou Toukoni Kounako Dossorola ! Salle Siguima ! Keke Magassi ! ! Kon!goy Ou!aro ! Dampha Ma!rela Bal!lala ! Dou!bala ! Segue D.T. -

He Role of Small Rice Mills in the Rice Subsector of the Office Du Niger, Mali.” Plan B Paper, Michigan State University

Staff Paper The Reform of Rice Milling and Marketing in the Office Du Niger: Catalyst for an Agricultural Success Story in Mali Salifou Bakary Diarra, John M. Staatz, R. James Bingen, and Niama Nango Dembélé Staff Paper No. 99-26 June 1999 Department of Agricultural Economics MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY East Lansing, Michigan 48824 MSU is an Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Institution THE REFORM OF RICE MILLING AND MARKETING IN THE OFFICE DU NIGER: CATALYST FOR AN AGRICULTURAL SUCCESS STORY IN MALI by Salifou Bakary Diarra, John M. Staatz, R. James Bingen, and Niama Nango Dembélé [email protected] [email protected] Chapter for forthcoming book Democracy and Development in Mali, edited by R. James Bingen, David Robinson and John M. Staatz. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press. MSU Agricultural Economics Staff Paper 99-26 June 1999. 20 pages total Copyright © 1999 by Salifou Bakary Diarra, John M. Staatz, R. James Bingen, and Niama Nango Dembélé. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this documents for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. THE REFORM OF RICE MILLING AND MARKETING IN THE OFFICE DU NIGER: CATALYST FOR AN AGRICULTURAL SUCCESS STORY IN MALI by Salifou Bakary Diarra, John M. Staatz, R. James Bingen, and Niama Nango Dembélé 1. INTRODUCTION One of the great successes of Malian economic policy during the 1980s and 1990s has been the transformation of the rice subsector. Domestic production shot up dramatically, growing at an annual rate of 9% between 1980 and 1997, largely due to yield increases in the irrigated area of the Office du Niger. -

REGION DE SEGOU Cercle De NIONO

PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ---------------------- Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi Commissariat à la Sécurité Alimentaire (CSA) ----------------------- Projet de Mobilisation des Initiatives en matière de Sécurité Alimentaire au Mali (PROMISAM) REGION DE SEGOU Cercle de NIONO Elaboré avec l’appui technique et financier de l’USAID-Mali à travers le projet d’appui au CSA, le PROMISAM Février 2008 2 I- INTRODUCTION: 1.1 Contexte de l'élaboration du Programme de Sécurité Alimentaire: Le Cercle de Niono à l'instar de l'ensemble du territoire national malien est exposé à un risque quasi annuel d'insécurité alimentaire. Les plus hautes Autorités du pays à travers le Commissariat à la Sécurité Alimentaire ont décidé de doter le pays d'un outil de prévention et de gestion des crises alimentaires dénommé Programme National de Sécurité Alimentaire (PNSA). Ce programme est la traduction de la Stratégie Nationale de Sécurité Alimentaire SNSA adoptée en 2002 par le gouvernement de la République du Mali; ce qui na conduit à l'adoption du cadre institutionnel en 2003. Ce cadre est conforme au processus de décentralisation. Il implique les niveaux national, régional, local et communal. Tous les acteurs participent aux instances de concertation et de coordination prévues à ces niveaux. Les défis et les enjeux de la Stratégie Nationale de Sécurité Alimentaire sont: ♣ nourrir une population en forte croissance et de plus en plus urbaine, ♣ asseoir la croissance des revenus ruraux sur une stratégie de croissance rapide du secteur agricole, ♣ affronter la diversité des crises alimentaires, ♣ intégrer la gestion des de La Sécurité alimentaire dans le processus de décentralisation et de reforme de l'Etat. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Commercial Irrigated Agriculture Development Project (P159765) Public Disclosure Authorized Project Information Document/ Integrated Safeguards Data Sheet (PID/ISDS) Public Disclosure Authorized Concept Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 20-Apr-2017 | Report No: PIDISDSC17562 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Sep 27, 2017 Page 1 of 15 The World Bank Commercial Irrigated Agriculture Development Project (P159765) BASIC INFORMATION A. Basic Project Data Country Project ID Parent Project ID (if any) Project Name Mali P159765 Commercial Irrigated Agriculture Development Project (P159765) Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) AFRICA Mar 19, 2018 May 29, 2018 Water Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Investment Project Financing Minister for Spatial Planning Ministry of Agriculture and Population Financing (in USD Million) Financing Source Amount International Development Association (IDA) 150.00 Total Project Cost 150.00 Environmental Assessment Category Concept Review Decision A-Full Assessment Track II-The review did authorize the preparation to continue Other Decision (as needed) Type here to enter text B. Introduction and Context Country Context 1. Mali is one of the world’s poorest countries, with a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of US$704.50 in 2014. Life expectancy is low (57 years of age); malnutrition levels are high (28 percent of under five children are stunted); and most of the 17.1 million population is illiterate (69 percent of adults). The economy of this landlocked country is predominantly rural and informal: 64 percent of the population resides in rural areas, and 80 percent of the jobs are in the informal sector. 2. The incidence of poverty is high and predominantly rural. -

Région De Segou-Mali

! ! ! RÉGION DE SEGOU - MALI ! Map No: MLIADM22304 7°0'W 6°0'W 5°0'W 4°0'W M A U R I T A N I E !Ambiri-Habe Tissit ! CER CLE S E T CO M MU NE S D E SÉ GO U ! Enghem ! Nourani ! Gathi-Loumo ! Boua Moussoule SÉGOU BLA El Massouka 30 Communes 17 Communes ! ! Korientzé RÉGION DE SÉGOU Kolima ! ! Fani ! ! BellenYouwarou ! ! Guidio-Saré Kazangasso Koulandougou Sansanding ! ! Togou Touna ! P Chef-lieu Région Route Principale ! Dougabougou ! Korodougou Boussin Diena ! Diona Yangasso ! ! Chef-lieu Cercle Route Secondaire ! ! Sibila ! ! ! Tiemena Kemeni Gueneibé Zoumane ! ! ! Nampala NKoumandougou !Sendegué ! ! Farakou Massa Niala Dougouolo Chef-lieu Commune Piste ! ! ! ! Dioro ! ! ! ! ! Samabogo ! Boumodi Magnale Baguindabougou Beguene ! ! ! Dianweli ! ! ! Kamiandougou Village Frontière Internationale Bouleli Markala ! Toladji ! ! Diédougou 7 ! Diganibougou ! Falo ! Tintirabe ! ! Diaramana ! Fatine Limite Région ! ! Aéroport/Aérodrome Souba ! Belel !Dogo ! ! ! Diouna 7 ! Sama Foulala Somasso ! Nara ! Katiéna Farako ! Limite Cercle ! Cinzana N'gara ! Bla Lac ! ! Fleuve Konodimini ! ! Pelengana Boré Zone Marécageuse Massala Ségou Forêts Classées/Réserves Sébougou Saminé Soignébougou Sakoiba MACINA 11 Communes Monimpébougou ! N Dialloubé N ' ! ' 0 0 ° ° 5 C!ette carte a été réalisée selon le découpage administratif du Mali à partir des SAN 5 1 doGnnoéuems bdoe ula Direction Nationale des Collectivités Territoriales (DNCT). N I O N O 25 Communes Macina 1 Kokry Centre !Borko ! Sources: ! Souleye ! ! Konna Boky Were ! ! - Direction Nationale des Collectivités -

S2mv1905mlia0l-Mliadm223-Mali.Pdf

CARTE ADMINISTRATIVE - MALI Map No: MLIADM223 12°0'W 10°0'W 8°0'W 6°0'W 4°0'W 2°0'W 0°0' 2°0'E 4°0'E !! El Mzereb RÉPUBLIQUE DU MALI CARTE DE RÉFÉRENCE !^ Capitale Nationale Route Principale Ts!alabia Plateau N N ' ' 0 0 ° ° 4 ! 4 2 .! Chef-lieu Région Route Secondaire 2 ! ! Chef-lieu Cercle Frontière Internationale ! Dâyet Boû el Athem ! Chef-lieu Commune Limite Région ! Teghaza 7 Aéroport Fleuve Réserve/Forêts Classées Lac Zone Marécageuse ! A L G É R I E ! Bir Chali Cette carte a été réalisée selon le découpage administratif du Mali à partir des données de la Direction Nationale des Collectivités Territoriales (DNCT). ! Taoudenni ! Sources: Agorgot - Direction Nationale des Collectivités Territroriales (DNCT), Mali - Esri, USGS, NOAA - Open Street Map !In Dagouber Coordinate System: Geographic N N ' ! ' 0 Datum : WGS 1984 El Ghetara 0 ° ° 2 2 2 2 1:2,200,000 0 100 200 Tazouikert ! ! Kilometres ! ! Bir Ouane Tamanieret Oumm El Jeyem ! ! ! In-Afarak http://mali.humanitarianresponse.info El Ksaib Tagnout Chagueret ! In Techerene ! Foum El Alba ! ! Amachach Kal Tessalit ! ! Tessalit Taounnant In Echai ! ! N N ' Boughessa! ' 0 0 ° ° 0 ! ! 0 2 ! 2 ! Tanezrouft pist Tinzawatène Kal Tadhak Telakak ! T O M B O U C T O U Taghlit ! Bezzeg Tin Tersi ! K I D A L ! Iradjanatene Tassendjit! ! Tin Ezeman ! Tin Karr ! Aguel-Hoc Ouan Madroin! ! ! Adrar Tin Oulli Inabag ! ! Tafainak ! El M! raiti ! Inabag Kal Relle Tadjmart Avertissement: Les limites, les noms et les désignations utilisés sur cette carte n’impliquent pas une reconnaissance ! Abeïbara Elb Techerit ! ou acceptation officielle des Nations Unies. -

Agricultural Investments and Land Acquisitions in Mali: Context, Trends and Case Studies

Agricultural investments and land acquisitions in Mali: Context, trends and case studies Moussa Djiré with Amadou Keita and Alfousseyni Diawara Agricultural investments and land acquisitions in Mali: Context, trends and case studies Moussa Djiré with Amadou Keita and Alfousseyni Diawara Agricultural investments and land acquisitions in Mali: Context, trends and case studies is the translation of Investissements agricoles et acquisitions foncières au Mali : Tendances et études de cas, first published in English by the International Institute for Environment and Development (UK) in 2012. Copyright © International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) All rights reserved ISBN: 978-1-84369-888-3 ISSN: 2225-739X (print) ISSN: 2227-9954 (online) For copies of this publication, please contact IIED: International Institute for Environment and Development 80-86 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8NH United Kingdom Email: [email protected] www.iied.org/pubs IIED order no.: 10037IIED A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Citation: Djiré, M. with Keita, A. and Diawara, A. (2012) Agricultural investments and land acquisitions in Mali: Context, trends and case studies. IIED/GERSDA, London/ Bamako. Translation from French: Jean Lubbock MITI MIL Cover photo: A young woman walks past a roadside map of the Office du Niger area, Mali © Sven Torfinn | Panos Cartography: C. D’Alton Design: Smith+Bell (www.smithplusbell.com) Printing: Park Communications (www.parkcom.co.uk). Printed with vegetable oil based inks on Chorus -

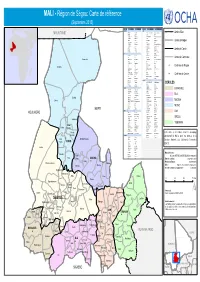

Mli0003 Ref Region De Segou A3 09092013

MALI - Région de Ségou: Carte de référence (Septembre 2013) CERCLE COMMUNE CHEF LIEU CERCLE COMMUNE CHEF LIEU BARAOUELI SAN BARAOUELI Baraouéli BARAMANDOUGOU Baramandougou Limite d'Etat MAURITANIE BOIDIE Boidié DAH Dah DOUGOUFIE Dougoufié DIAKOUROUNA Diakourouna Nerissso GOUENDO Gouendo DIELI Diéli KALAKE Kalaké DJEGUENA Djéguena Limite de Région KONOBOUGOU Konobougou FION Fion N'GASSOLA N'Gassola KANIEGUE Dioundiou Konkankan SANANDO Sanando KARABA Karaba Kagoua SOMO Somo KASSOROLA Nianaso TAMANI Tamani KAVA Kimparana Limite de Cercle TESSERELA Tesserla MORIBILA Moribila‐Kagoua BLA N'GOA N'Goa BENGUENE Beguené NIAMANA Niamana Sobala BLA Bla NIASSO Niasso Limite de Commune Nampalari DIARAMANA Diaramana N'TOROSSO N'Torosso Bolokalasso DIENA Diéna OUOLON Ouolon DOUGOUOLO Dougouolo SAN San FALO Falo SIADOUGOU Siélla .! Chef-lieu de Région Dogofry FANI Fani SOMO Somo KAZANGASSO Kazangasso SOUROUNTOUNA Sourountouna KEMENI Kémeni SY Sy KORODOUGOU Nampasso TENE Tené ! KOULANDOUGOU N'Toba TENENI Ténéni Chef-lieu de Cercle NIALA Niala TOURAKOLOMBA Toura‐Kalanga SAMABOGO Samabogo WAKY Waki1 SOMASSO Somasso SEGOU TIEMENA Tiémena BAGUIDADOUGOU Markanibougou TOUNA Touna BELLEN Sagala CERCLES YANGASSO Yangasso BOUSSIN Boussin MACINA CINZANA Cinzana Gare BOKY WERE Boky‐Weré DIGANIBOUGOU Digani BARAOUELI FOLOMANA Folomana DIORO Dioro KOKRY Kokry‐Centre DIOUNA Diouna KOLONGO Kolongotomo DJEDOUGOU Yolo BLA Diabaly MACINA Macina DOUGABOUGOU Dougabougou Koroni MATOMO Matomo‐Marka FARAKO Farako Sokolo MONIMPEBOUGOU Monimpébougou FARAKOU MASSA Kominé MACINA -

And Cosmopolitan Workers: Technological Masculinity and Agricultural Development in the French Soudan (Mali), 1945–68’ Gender & History, Vol.26 No.3 November 2014, Pp

Gender & History ISSN 0953-5233 Laura Ann Twagira, ‘“Robot Farmers” and Cosmopolitan Workers: Technological Masculinity and Agricultural Development in the French Soudan (Mali), 1945–68’ Gender & History, Vol.26 No.3 November 2014, pp. 459–477. ‘Robot Farmers’ and Cosmopolitan Workers: Technological Masculinity and Agricultural Development in the French Soudan (Mali), 1945–68 Laura Ann Twagira In 1956, Administrator Ancian, a French government official, suggested in a con- fidential report that one of the most ambitious agricultural schemes in French West Africa, the Office du Niger, had been misguided in its planning to produce only a ‘robot farmer’.1 The robot metaphor was no doubt drawn from the intense association between the project and technology. However, it was a critical analogy suggesting alienation. By using the word ‘robot’, Ancian implied that, rather than developing the project with the economic and social needs of the individual farmer in mind, the colonial Office du Niger was designed so that indistinguishable labourers would follow the dictates of a strictly regulated agricultural calendar. In effect, farmers were meant simply to become part of a larger agricultural machine, albeit a machine of French design. The robot comparison also belied Ancian’s ambivalence about the impact of technological development and modernity in Africa.2 He was reiterating a long-standing concern of French officials who worried that change in rural African society would lead to social breakdown and create the necessity for the colonial state to support and rein- force patriarchal social structures in the French Soudan.3 The image of a robot farmer, which suggested an unnatural combination, also gestured toward an uncertain future in which African farmers would employ industrial agricultural technology without fully comprehending it.