A Synthesis of Schenkerian and Neo-Riemannian Theories: the First Movement of Paul Hindemith’S Piano Sonata No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.1 Review by David Carson Berry After Allen Forte’s and Steven Gilbert’s Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis was published in 1982, it effectively had the textbook market to itself for a decade (a much older book by Felix Salzer and a new translation of one by Oswald Jonas not withstanding).2 A relatively compact Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping, was issued in 1992;3 and in 1998 came Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné’s Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, which is today (in its third edition) the dominant text.4 Despite its ascendance, and the firm legacy of the Forte/Gilbert book, authors continue to crowd what is a comparatively small market within music studies. Steven Porter offered the interesting but dubiously named Schenker Made Simple in 1 Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form, by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012; hardback, $150 (978-0- 415-89214-8), paperback, $68.95 (978-0-415-89215-5); xx, 310 pp. 2 Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: Norton, 1982). Felix Salzer’s book (Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music [New York: Charles Boni, 1952]), though popular in its time, was viewed askance by orthodox Schenkerians due to its alterations of core tenets, and it was growing increasingly out of favor with mainstream theorists by the 1980s (as evidenced by the well-known rebuttal of its techniques in Joseph N. -

Burn Approved Final Document (With JB Edits)

The German Romantic Style of Paul Hindemith's Piano Sonata no. 1 "Der Main" Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Burn, Douglas-Jayd Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 10:14:24 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631332 1 THE GERMAN ROMANTIC STYLE OF PAUL HINDEMITH’S PIANO SONATA NO. 1 “DER MAIN” by Douglas-Jayd Burn __________________________ Copyright © Douglas-Jayd Burn 2018 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2018 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This document has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this document are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Douglas-Jayd Burn 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A document like this takes a village to prepare and it is not possible to thank everyone who has been a part of the process, but I would like to express my thanks to the following: I am sincerely grateful to my major professor Dr. -

Wandlungen in Paul Hindemiths Bach-Verständnis Welches

BACH-BILDER IM 20. JAHRHUNDERT Hermann Danuser: DER KLASSIKER ALS JANUS? Wandlungen in Paul Hindemiths Bach-Verständnis Welches theoretische Modell man auch immer für den Gegenstand einer "Wirkungs-" oder "Rezeptionsgeschichte" bevorzugt - man kann, um grob zu kontrastieren, entweder von der Vielgestaltigkeit eines OEuvres ausgehen, dessen geistig-künstlerische Potenz auf Zeit- genossenschaft und Nachwelt "wirkt", oder aber von der Mannigfaltigkeit der Konkreti- sierungen, in denen Mit- und Nachwelt ein OEuvre "rezipiert" - , in jedem Fall darf man dem \~erk Johann Sebastian Bachs seit dem 19. Jahrhundert den Status der Klassizität beimessen, später gar - so meine ich - den einer Universalität, die von der Musik keines anderen Komponisten übertroffen oder auch nur erreicht worden ist. Dies gilt auch für die erste Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, in kompositionsgeschichtlicher Hinsicht für diesen Zeitraum sogar ganz besonders, überdauerte doch Bach als einziger Klassiker die musikhistorische Epochenzäsur um 1920 in ungeschmälertem Maße, indem er für Roman- tik und Moderne vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg ebenso wie danach für beide Richtungen des Neoklassizismus, für die neotonale Strawinskys und Hindemiths nicht minder als für die dodekaphone der Schönberg-Schule, von freilich verschiedenartiger, stets wieder erneu- erter Bedeutung war und blieb. Solch dauerhafte Geltung aber ist undenkbar ohne tief- greifendste Wandlungen in den Rezeptionsaspekten der Bachsehen Musik. Wer sich nun das Bach-Bild Paul Hindemiths vergegenwärtigt, wird wohl zuerst an -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Schenkerian Analysis in the Modern Context of the Musical Analysis

Mathematics and Computers in Biology, Business and Acoustics THE SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS IN THE MODERN CONTEXT OF THE MUSICAL ANALYSIS ANCA PREDA, PETRUTA-MARIA COROIU Faculty of Music Transilvania University of Brasov 9 Eroilor Blvd ROMANIA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - Music analysis represents the most useful way of exploration and innovation of musical interpretations. Performers who use music analysis efficiently will find it a valuable method for finding the kind of musical richness they desire in their interpretations. The use of Schenkerian analysis in performance offers a rational basis and an unique way of interpreting music in performance. Key-Words: - Schenkerian analysis, structural hearing, prolongation, progression,modernity. 1 Introduction Even in a simple piece of piano music, the ear Musical analysis is a musicological approach in hears a vast number of notes, many of them played order to determine the structural components of a simultaneously. The situation is similar to that found musical text, the technical development of the in language. Although music is quite different to discourse, the morphological descriptions and the spoken language, most listeners will still group the understanding of the meaning of the work. Analysis different sounds they hear into motifs, phrases and has complete autonomy in the context of the even longer sections. musicological disciplines as the music philosophy, Schenker was not afraid to criticize what he saw the musical aesthetics, the compositional technique, as a general lack of theoretical and practical the music history and the musical criticism. understanding amongst musicians. As a dedicated performer, composer, teacher and editor of music himself, he believed that the professional practice of 2 Problem Formulation all these activities suffered from serious misunderstandings of how tonal music works. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By YANG-MING SUN Norman, Oklahoma 2007 UMI Number: 3263429 UMI Microform 3263429 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY Dr. Edward Gates, chair Dr. Jane Magrath Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Sarah Reichardt Dr. Fred Lee © Copyright by YANG-MING SUN 2007 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is dedicated to my beloved parents and my brother for their endless love and support throughout the years it took me to complete this degree. Without their financial sacrifice and constant encouragement, my desire for further musical education would have been impossible to be fulfilled. I wish also to express gratitude and sincere appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Edward Gates, for his constructive guidance and constant support during the writing of this project. Appreciation is extended to my committee members, Professors Jane Magrath, Eugene Enrico, Sarah Reichardt and Fred Lee, for their time and contributions to this document. Without the participation of the writing consultant, this study would not have been possible. I am grateful to Ms. Anna Holloway for her expertise and gracious assistance. Finally I would like to thank several individuals for their wonderful friendships and hospitalities. -

Tonality and Transformation, by Steven Rings. Oxford Studies in Music Theory

Tonality and Transformation, by Steven Rings. Oxford Studies in Music Theory. Richard Cohn, series editor. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. xiv + 243 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-538427-7. $35 (Hardback).1 Reviewed by William O’Hara Harvard University teven Rings’ Tonality and Transformation is only one entry in a deluge of recent volumes1 in the Oxford Studies in Music Theory series,2 but its extension of the transformational ideas pioneered by S scholars like David Lewin, Brian Hyer, and Richard Cohn into the domain of tonal music sets it apart as a significant milestone in contemporary music theory. Through the “technologies” of transformational theory, Rings articulates his nuanced perspective on tonal hearing by mixing in generous helpings of Husserlian philosophy and mathematical graph theory, and situating the result in a broad historical context. The text is also sprinkled throughout with illuminating methodological comments, which weave a parallel narrative of analytical pluralism by bringing transformational ideas into contact with other modes of analysis (primarily Schenkerian theory) and arguing that they can complement rather than compete with one another. Rings manages to achieve all this in 222 concise pages that will prove both accessible to students and satisfying for experts, making the book simultaneously a substantial theoretical contribution, a valuable exposition of existing transformational ideas, and an exhilarating case study for creative, interdisciplinary music theorizing. [2] Tonality and Transformation is divided into two parts. The first three chapters constitute the theory proper—a reimagining of tonal music theory from the ground up, via the theoretical technologies mentioned above. The final 70 pages consist of four analytical essays, which begin to put Rings’ ideas into practice. -

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

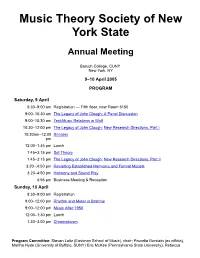

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

In Ludus Tonalis

Grand Valley Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 4 2001 The rC eative Process vs. The aC non Kurt J. Ellenberger Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr Recommended Citation Ellenberger, Kurt J. (2001) "The rC eative Process vs. The aC non," Grand Valley Review: Vol. 23: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr/vol23/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grand Valley Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. by Kurt J. Ellenberger frenzied and unforh The Creative Process vs. for "originality" (as trinsic value in and greatest composers a The Canon in a variety of differe as a testament to thE Hindemith Recycles in Ludus Tonalis in our own contempc necessary for today' s ways in which this w he contemporary composer faces many ob confines of a centuri Tstacles in the struggle towards artistic inde apparently still capab pendence. Not the least of these is the solemn music) in the hopes th realization that one's work will inevitably be might show themsel compared to the countless pieces of music that expression of our ow define the tradition of musical achievement as canonized in the "Literature." Another lies in the he need for one's mandate (exacerbated in this century by the T logical outgrowtl academy's influence) that, to qualify as innova ently a powerful 01 tive or original, a work must utilize some new influence. -

Analyzing Fugue: a Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick

Analyzing Fugue: A Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick. Harmonologia Series No. 8 (edited by Joel Lester). Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press, 1995. Review by Robert Gauldin In recent years focus has tended to shift from Heinrich Schenker's canonical principles of hierarchical voice leading to his comments on musical form, as formulated in the final section of Der freie Satz.1 While Schenker's middleground and background levels are eminently suited for revealing the tonal structure of such designs as ternary and sonata, their application to other formal genres raises certain questions.2 Aside from his essay on organicism in the fugue, which deals with the C Minor fugue in WTC I, Schenker rarely ventured into contrapuntal genres.3 In fact, only a handful of fugal analyses exist in subsequent Schenkerian literature.4 It is ^See his Free Composition. 2 vols. Translated and edited by Ernst Oster. (New York: Longman, 1979), 1:128-45. ^In this regard, Joel Garland and Charles Smith have recently explored spe- cific aspects of rondo and variation form, respectively. See Garland's "Form, Genre, and Style in the Eighteenth-Century Rondo," Music Theory Spectrum 17/1 (Spring 1995), 27-52, and Smith's "Head-Tones, Mediants, Reprises: A Formal Narrative of Brahms' Handel Variations," paper deliv- ered at the Eastman School of Music, March 1995. In the latter, interest centers around^ Variation 21, where the original Urlinie 3-2-1 in Bb major is now set as 5-4-3 in the relative minor key. A similar problem of Urlinie reinterpretation occurs in Brahms' Haydn Variations Op. -

The Piano Improvisations of Chick Corea: an Analytical Study

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 The iP ano Improvisations of Chick Corea: An Analytical Study. Daniel Alan Duke Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Duke, Daniel Alan, "The iP ano Improvisations of Chick Corea: An Analytical Study." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6334. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6334 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the te d directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The University of Chicago an Experience-Oriented

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AN EXPERIENCE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO ANALYZING STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY SARAH MARIE IKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction: Analysis, Experience, and Experience-Oriented Analysis ..................................... 1 1 Neoclassicism, Analysis, and Experience ................................................................................ 10 1.1 Neoclassicism After the Great War ................................................................................. 10 1.2 Analyzing Neoclassicism: Problems and Solutions ....................................................... 18 1.3 Whence Listener Experience? ........................................................................................... 37 1.4 The Problem of Historicism ............................................................................................