A Schenkerian Analysis of Ravel's Introduction And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.1 Review by David Carson Berry After Allen Forte’s and Steven Gilbert’s Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis was published in 1982, it effectively had the textbook market to itself for a decade (a much older book by Felix Salzer and a new translation of one by Oswald Jonas not withstanding).2 A relatively compact Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping, was issued in 1992;3 and in 1998 came Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné’s Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, which is today (in its third edition) the dominant text.4 Despite its ascendance, and the firm legacy of the Forte/Gilbert book, authors continue to crowd what is a comparatively small market within music studies. Steven Porter offered the interesting but dubiously named Schenker Made Simple in 1 Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form, by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012; hardback, $150 (978-0- 415-89214-8), paperback, $68.95 (978-0-415-89215-5); xx, 310 pp. 2 Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: Norton, 1982). Felix Salzer’s book (Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music [New York: Charles Boni, 1952]), though popular in its time, was viewed askance by orthodox Schenkerians due to its alterations of core tenets, and it was growing increasingly out of favor with mainstream theorists by the 1980s (as evidenced by the well-known rebuttal of its techniques in Joseph N. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

The Rosenwinkel Introductions

The Rosenwinkel Introductions: Stylistic Tendencies in 10 Introductions Recorded by Jazz Guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel Jens Hoppe A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I, Jens Hoppe, hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: ______________________________________________Date: 31 March 2016 i Acknowledgments The task of writing a thesis is often made more challenging by life’s unexpected events. In the case of this thesis, it was burglary, relocation, serious injury, marriage, and a death in the family. Disruptions also put extra demands on those surrounding the writer. I extend my deepest gratitude to the following people for, above all, their patience and support. To my supervisor Phil Slater without whom this thesis would not have been possible – for his patience, constructive comments, and ability to say things that needed to be said in a positive and encouraging way. Thank you Phil. To Matt McMahon, who is always an inspiration, whether in conversation or in performance. To Simon Barker, for challenging some fundamental assumptions and talking about things that made me think. To Troy Lever, Abel Cross, and Pete ‘Göfren’ for their help in the early stages. They are not just wonderful musicians and friends, but exemplary human beings. To Fletcher and Felix for their boundless enthusiasm, unconditional love and the comic relief they provided. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Schenkerian Analysis in the Modern Context of the Musical Analysis

Mathematics and Computers in Biology, Business and Acoustics THE SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS IN THE MODERN CONTEXT OF THE MUSICAL ANALYSIS ANCA PREDA, PETRUTA-MARIA COROIU Faculty of Music Transilvania University of Brasov 9 Eroilor Blvd ROMANIA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - Music analysis represents the most useful way of exploration and innovation of musical interpretations. Performers who use music analysis efficiently will find it a valuable method for finding the kind of musical richness they desire in their interpretations. The use of Schenkerian analysis in performance offers a rational basis and an unique way of interpreting music in performance. Key-Words: - Schenkerian analysis, structural hearing, prolongation, progression,modernity. 1 Introduction Even in a simple piece of piano music, the ear Musical analysis is a musicological approach in hears a vast number of notes, many of them played order to determine the structural components of a simultaneously. The situation is similar to that found musical text, the technical development of the in language. Although music is quite different to discourse, the morphological descriptions and the spoken language, most listeners will still group the understanding of the meaning of the work. Analysis different sounds they hear into motifs, phrases and has complete autonomy in the context of the even longer sections. musicological disciplines as the music philosophy, Schenker was not afraid to criticize what he saw the musical aesthetics, the compositional technique, as a general lack of theoretical and practical the music history and the musical criticism. understanding amongst musicians. As a dedicated performer, composer, teacher and editor of music himself, he believed that the professional practice of 2 Problem Formulation all these activities suffered from serious misunderstandings of how tonal music works. -

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models By: Irna Priore ―Further Considerations about the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker’s Five Interruption Models.‖ Indiana Theory Review, Volume 25, Spring-Fall 2004 (spring 2007). Made available courtesy of Indiana University School of Music: http://www.music.indiana.edu/ *** Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Article: Schenker’s works span about thirty years, from his early performance editions in the first decade of the twentieth century to Free Composition in 1935.1 Nevertheless, the focus of modern scholarship has most often been on the ideas contained in this last work. Although Free Composition is indeed a monumental accomplishment, Schenker's early ideas are insightful and merit further study. Not everything in these early essays was incorporated into Free Composition and some ideas that appear in their final form in Free Composition can be traced back to his previous writings. This is the case with the discussion of interruption, a term coined only in Free Composition. After the idea of the chord of nature and its unfolding, interruption is probably the most important concept in Free Composition. In this work Schenker studied the implications of melodic descent, referring to the momentary pause of this descent prior to the achievement of tonal closure as interruption. In his earlier works he focused more on the continuity of the line itself rather than its tonal closure, and used the notion of melodic line or melodic continuity to address long-range connections. -

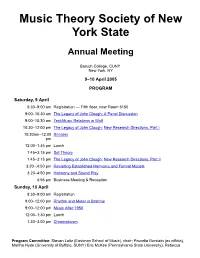

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

Understanding Ornamentation in Atonal Music Michael Buchler College of Music, Florida State University, U.S.A

Understanding Ornamentation in Atonal Music Michael Buchler College of Music, Florida State University, U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT # j E X. X E In 1987, Joseph Straus convincingly argued that prolongational & E claims were unsupportable in post-tonal music. He also, intentionally or not, set the stage for a slippery slope argument whereby any small E # E E E morsel of prolongationally conceived structure (passing tones, ? E neighbor tones, suspensions, and the like) would seem just as Example 1. An escape tone that is not “non-harmonic.” problematic as longer-range harmonic or melodic enlargements. Prolongational structures are hierarchical, after all. This paper argues Example 2 excerpts an oft-contemplated piece: that large-scale prolongations are inherently different from Schoenberg’s op. 19, no. 6. In mm. 3-4, E6, the highest note small-scale ones in atonal (and possibly also tonal) music. It also of this short movement, neighbors Ds6. This neighboring suggests that we learn to trust our analytical instincts and perceptions motion is the first new gesture that we hear following with atonal music as much as we do with tonal music and that we not repetitions of the iconic first two chords. Two bars later, we require every interpretive impulse to be grounded by strongly can hear an appoggiatura as the unprepared Gs enters and methodological constraints. resolves down to Fs. The Ds-E-Ds neighbor tone was also shown in a reductive analysis in Lerdahl (2001, 354), but I. INTRODUCTION AND EXAMPLES Lerdahl apparently disagrees with my appoggiatura designation, instead equating both Gs and Fs as members of On the face of it, this paper makes a very simple and “departure” sonorities. -

A Framework for Automated Schenkerian Analysis

ISMIR 2008 – Session 3b – Computational Musicology A FRAMEWORK FOR AUTOMATED SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS Phillip B. Kirlin and Paul E. Utgoff Department of Computer Science University of Massachusetts Amherst Amherst, MA 01003 {pkirlin,utgoff}@cs.umass.edu ABSTRACT [1] in a hierarchical manner. Schenker’s theory of music al- lows one to determine which notes in a passage of music In Schenkerian analysis, one seeks to find structural de- are more structurally significant than others. It is important pendences among the notes of a composition and organize not to confuse “structural significance” with “musical im- these dependences into a coherent hierarchy that illustrates portance;” a musically important note (e.g., crucial for artic- the function of every note. This type of analysis reveals ulating correctly in a performance) can be a very insignifi- multiple levels of structure in a composition by construct- cant tone from a structural standpoint. Judgments regarding ing a series of simplifications of a piece showing various structural importance result from finding dependences be- elaborations and prolongations. We present a framework tween notes or sets of notes: if a note X derives its musical for solving this problem, called IVI, that uses a state-space function or meaning from the presence of another note Y , search formalism. IVI includes multiple interacting compo- then X is dependent on Y and Y is deemed more structural nents, including modules for various preliminary analyses than X. (harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, and cadential), identifying The process of completing a Schenkerian analysis pro- and performing reductions, and locating pieces of the Ur- ceeds in a recursive manner. -

Evaluating Prolongation in Extended Tonality

Evaluating Prolongation in Extended Tonality <http://mod7.shorturl.com/prolongation.htm> Robert T. Kelley Florida State University In this paper I shall offer strategies for deciding what is structural in extended-tonal music and provide new theoretical qualifications that allow for a conservative evaluation of prolongational analyses. Straus (1987) provides several criteria for finding post-tonal prolongation, but these can simply be reduced down to one important consideration: Non-tertian music clouds the distinction between harmonic and melodic intervals. Because linear analysis depends upon this distinction, any expansion of the prolongational approach for non-tertian music must find alternative means for defining the ways in which transient tones elaborate upon structural chord tones to foster a sense of prolongation. The theoretical work that Straus criticizes (Salzer 1952, Travis 1959, 1966, 1970, Morgan 1976, et al.) fails to provide a method for discriminating structural tones from transient tones. More recently, Santa (1999) has provided associational models for hierarchical analysis of some post-tonal music. Further, Santa has devised systems for determining salience as a basis for the assertion of structural chords and melodic pitches in a hierarchical analysis. While a true prolongational perspective cannot be extended to address most post-tonal music, it may be possible to salvage a prolongational approach in a restricted body of post-tonal music that retains some features of tonality, such as harmonic function, parsimonious voice leading, or an underlying diatonic collection. Taking into consideration Straus’s theoretical proviso, we can build a model for prolongational analysis of non-tertian music by establishing how non-tertian chords may attain the status of structural harmonies. -

Analyzing Fugue: a Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick

Analyzing Fugue: A Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick. Harmonologia Series No. 8 (edited by Joel Lester). Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press, 1995. Review by Robert Gauldin In recent years focus has tended to shift from Heinrich Schenker's canonical principles of hierarchical voice leading to his comments on musical form, as formulated in the final section of Der freie Satz.1 While Schenker's middleground and background levels are eminently suited for revealing the tonal structure of such designs as ternary and sonata, their application to other formal genres raises certain questions.2 Aside from his essay on organicism in the fugue, which deals with the C Minor fugue in WTC I, Schenker rarely ventured into contrapuntal genres.3 In fact, only a handful of fugal analyses exist in subsequent Schenkerian literature.4 It is ^See his Free Composition. 2 vols. Translated and edited by Ernst Oster. (New York: Longman, 1979), 1:128-45. ^In this regard, Joel Garland and Charles Smith have recently explored spe- cific aspects of rondo and variation form, respectively. See Garland's "Form, Genre, and Style in the Eighteenth-Century Rondo," Music Theory Spectrum 17/1 (Spring 1995), 27-52, and Smith's "Head-Tones, Mediants, Reprises: A Formal Narrative of Brahms' Handel Variations," paper deliv- ered at the Eastman School of Music, March 1995. In the latter, interest centers around^ Variation 21, where the original Urlinie 3-2-1 in Bb major is now set as 5-4-3 in the relative minor key. A similar problem of Urlinie reinterpretation occurs in Brahms' Haydn Variations Op. -

Allen Forte on Schenker

From Allen Forte: Schenker’s Conception of Musical Structure, in Journal of Music Theory, III/1 (April, 1959), 7 – 14, 23 – 24. Reprinted in Norton Critical Scores: Dichterliebe, edited by Arthur Komar.1 Note: I have modified Forte’s footnotes in two ways: first, I’ve added a number of footnotes of my own, pointing out where some of the unexamined assumptions of Schenkerian analysis might be fueling some of Forte’s or Schenker’s statements, and second, where the reference is sufficiently obscure as to be best omitted. Those footnotes which present my own commentary are always prefaced with my initials SLF. (Sometimes I’ve appended my commentary directly to Forte’s footnotes.) From time to time I may insert a larger-scale note into the text proper; such notes are formatted as you see here, in smaller italic text and enclosed in indented paragraphs. I can think of no more satisfactory way to introduce Schenker’s ideas, along with the terminology and visual means which express them, than to comment at some length upon one of his analytic sketches. For this purpose I have selected from Der freie Satz a sketch of a complete short work, the second song from Schumann’s Dichterliebe. I shall undertake to read and interpret this sketch, using, of course, English equivalents for Schenker’s terms.2 Here in visual form is Schenker’s conception of musical structure: the total work is regarded as an interacting composite of three main levels. Each of these structural levels is represented on a separate staff in order that its unique content may be clearly shown.