Concept of Tonality"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach

Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.1 Review by David Carson Berry After Allen Forte’s and Steven Gilbert’s Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis was published in 1982, it effectively had the textbook market to itself for a decade (a much older book by Felix Salzer and a new translation of one by Oswald Jonas not withstanding).2 A relatively compact Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, by David Neumeyer and Susan Tepping, was issued in 1992;3 and in 1998 came Allen Cadwallader and David Gagné’s Analysis of Tonal Music: A Schenkerian Approach, which is today (in its third edition) the dominant text.4 Despite its ascendance, and the firm legacy of the Forte/Gilbert book, authors continue to crowd what is a comparatively small market within music studies. Steven Porter offered the interesting but dubiously named Schenker Made Simple in 1 Advanced Schenkerian Analysis: Perspectives on Phrase Rhythm, Motive, and Form, by David Beach. New York and London: Routledge, 2012; hardback, $150 (978-0- 415-89214-8), paperback, $68.95 (978-0-415-89215-5); xx, 310 pp. 2 Allen Forte and Steven E. Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: Norton, 1982). Felix Salzer’s book (Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music [New York: Charles Boni, 1952]), though popular in its time, was viewed askance by orthodox Schenkerians due to its alterations of core tenets, and it was growing increasingly out of favor with mainstream theorists by the 1980s (as evidenced by the well-known rebuttal of its techniques in Joseph N. -

Science Fiction in Argentina: Technologies of the Text in A

Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Revised Pages DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS, an imprint of the University of Michigan Press, is dedicated to publishing work in new media studies and the emerging field of digital humanities. Revised Pages Science Fiction in Argentina Technologies of the Text in a Material Multiverse Joanna Page University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Joanna Page Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial- No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Page, Joanna, 1974– author. Title: Science fiction in Argentina : technologies of the text in a material multiverse / Joanna Page. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015044531| ISBN 9780472073108 (hardback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472053100 (paperback : acid- free paper) | ISBN 9780472121878 (e- book) Subjects: LCSH: Science fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | Literature and technology— Argentina. | Fantasy fiction, Argentine— History and criticism. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Science Fiction & Fantasy. | LITERARY CRITICISM / Caribbean & Latin American. Classification: LCC PQ7707.S34 P34 2016 | DDC 860.9/35882— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015044531 http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/dcbooks.13607062.0001.001 Revised Pages To my brother, who came into this world to disrupt my neat ordering of it, a talent I now admire. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Schenkerian Analysis in the Modern Context of the Musical Analysis

Mathematics and Computers in Biology, Business and Acoustics THE SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS IN THE MODERN CONTEXT OF THE MUSICAL ANALYSIS ANCA PREDA, PETRUTA-MARIA COROIU Faculty of Music Transilvania University of Brasov 9 Eroilor Blvd ROMANIA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - Music analysis represents the most useful way of exploration and innovation of musical interpretations. Performers who use music analysis efficiently will find it a valuable method for finding the kind of musical richness they desire in their interpretations. The use of Schenkerian analysis in performance offers a rational basis and an unique way of interpreting music in performance. Key-Words: - Schenkerian analysis, structural hearing, prolongation, progression,modernity. 1 Introduction Even in a simple piece of piano music, the ear Musical analysis is a musicological approach in hears a vast number of notes, many of them played order to determine the structural components of a simultaneously. The situation is similar to that found musical text, the technical development of the in language. Although music is quite different to discourse, the morphological descriptions and the spoken language, most listeners will still group the understanding of the meaning of the work. Analysis different sounds they hear into motifs, phrases and has complete autonomy in the context of the even longer sections. musicological disciplines as the music philosophy, Schenker was not afraid to criticize what he saw the musical aesthetics, the compositional technique, as a general lack of theoretical and practical the music history and the musical criticism. understanding amongst musicians. As a dedicated performer, composer, teacher and editor of music himself, he believed that the professional practice of 2 Problem Formulation all these activities suffered from serious misunderstandings of how tonal music works. -

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models

Further Considerations of the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker's Five Interruption Models By: Irna Priore ―Further Considerations about the Continuous ^5 with an Introduction and Explanation of Schenker’s Five Interruption Models.‖ Indiana Theory Review, Volume 25, Spring-Fall 2004 (spring 2007). Made available courtesy of Indiana University School of Music: http://www.music.indiana.edu/ *** Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Article: Schenker’s works span about thirty years, from his early performance editions in the first decade of the twentieth century to Free Composition in 1935.1 Nevertheless, the focus of modern scholarship has most often been on the ideas contained in this last work. Although Free Composition is indeed a monumental accomplishment, Schenker's early ideas are insightful and merit further study. Not everything in these early essays was incorporated into Free Composition and some ideas that appear in their final form in Free Composition can be traced back to his previous writings. This is the case with the discussion of interruption, a term coined only in Free Composition. After the idea of the chord of nature and its unfolding, interruption is probably the most important concept in Free Composition. In this work Schenker studied the implications of melodic descent, referring to the momentary pause of this descent prior to the achievement of tonal closure as interruption. In his earlier works he focused more on the continuity of the line itself rather than its tonal closure, and used the notion of melodic line or melodic continuity to address long-range connections. -

A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-2-2014 A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A. Labadorf University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Labadorf, Thomas A., "A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 332. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/332 A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A. Labadorf, D. M. A. University of Connecticut, 2014 A new transcription of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy is presented to offset limitations of previous transcriptions by other editors. Certain shortcomings of the clarinet are addressed which add to the difficulty of creating an effective transcription for performance: the inability to sustain more than one note at a time, phrase length limited by breath capacity, and a limited pitch range. The clarinet, however, offers qualities not available to the keyboard that can serve to mitigate these shortcomings: voice-like legato to perform sweeping scalar and arpeggiated gestures, the increased ability to sustain melodic lines, use of dynamics to emphasize phrase shapes and highlight background melodies, and the ability to perform large leaps easily. A unique realization of the arpeggiated section takes advantage of the clarinet’s distinctive registers and references early treatises for an authentic wind instrument approach. A linear analysis, prepared by the author, serves as a basis for making decisions on phrase and dynamic placement. -

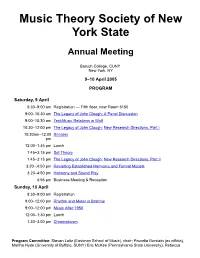

Program and Abstracts for 2005 Meeting

Music Theory Society of New York State Annual Meeting Baruch College, CUNY New York, NY 9–10 April 2005 PROGRAM Saturday, 9 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration — Fifth floor, near Room 5150 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion 9:00–10:30 am TextMusic Relations in Wolf 10:30–12:00 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part I 10:30am–12:00 Scriabin pm 12:00–1:45 pm Lunch 1:45–3:15 pm Set Theory 1:45–3:15 pm The Legacy of John Clough: New Research Directions, Part II 3:20–;4:50 pm Revisiting Established Harmonic and Formal Models 3:20–4:50 pm Harmony and Sound Play 4:55 pm Business Meeting & Reception Sunday, 10 April 8:30–9:00 am Registration 9:00–12:00 pm Rhythm and Meter in Brahms 9:00–12:00 pm Music After 1950 12:00–1:30 pm Lunch 1:30–3:00 pm Chromaticism Program Committee: Steven Laitz (Eastman School of Music), chair; Poundie Burstein (ex officio), Martha Hyde (University of Buffalo, SUNY) Eric McKee (Pennsylvania State University); Rebecca Jemian (Ithaca College), and Alexandra Vojcic (Juilliard). MTSNYS Home Page | Conference Information Saturday, 9:00–10:30 am The Legacy of John Clough: A Panel Discussion Chair: Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) Jack Douthett (University at Buffalo, SUNY) Nora Engebretsen (Bowling Green State University) Jonathan Kochavi (Swarthmore, PA) Norman Carey (Eastman School of Music) John Clough was a pioneer in the field of scale theory. -

Universality-Diversity Paradigm: Music, Materiomics, and Category Theory

Chapter 4 Universality-Diversity Paradigm: Music, Materiomics, and Category Theory Abstract The transition from the material structure to function, or from nanoscale components to the macroscale system, is a challenging proposition. Recognizing how Nature accomplishes such a feat—through universal structural elements, rel- atively weak building blocks, and self-assembly—is only part of the solution. The complexity bestowed by hierarchical multi-scale structures is not only found in bi- ological materials and systems—it arises naturally within other fields such as music or language, with starkly different functions. If we wish to exploit understanding of the structure of music as it relates to materials, we need to define the relevant properties and functional relations in an abstract sense. One approach may lie in category theory, presented here in the form of ontology logs (ologs), that can tran- scend the traditional definitions of materials, music, or language, in a consistent and mathematically robust manner. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White, The Elements of Style (1919) 4.1 Introduction To solve society’s most pressing problems, including medical, energy, and envi- ronmental challenges, we will need transformative, rather than evolutionary, ap- proaches. Many of these depend on finding materials with properties that are sub- stantially improved over existing candidates, and we are increasingly turning to complex materials. As discussed in the previous chapter, biological materials and systems present many challenges before we can “unlock” the secrets of Nature. -

Analyzing Fugue: a Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick

Analyzing Fugue: A Schenkerian Approach by William Renwick. Harmonologia Series No. 8 (edited by Joel Lester). Stuyvesant, New York: Pendragon Press, 1995. Review by Robert Gauldin In recent years focus has tended to shift from Heinrich Schenker's canonical principles of hierarchical voice leading to his comments on musical form, as formulated in the final section of Der freie Satz.1 While Schenker's middleground and background levels are eminently suited for revealing the tonal structure of such designs as ternary and sonata, their application to other formal genres raises certain questions.2 Aside from his essay on organicism in the fugue, which deals with the C Minor fugue in WTC I, Schenker rarely ventured into contrapuntal genres.3 In fact, only a handful of fugal analyses exist in subsequent Schenkerian literature.4 It is ^See his Free Composition. 2 vols. Translated and edited by Ernst Oster. (New York: Longman, 1979), 1:128-45. ^In this regard, Joel Garland and Charles Smith have recently explored spe- cific aspects of rondo and variation form, respectively. See Garland's "Form, Genre, and Style in the Eighteenth-Century Rondo," Music Theory Spectrum 17/1 (Spring 1995), 27-52, and Smith's "Head-Tones, Mediants, Reprises: A Formal Narrative of Brahms' Handel Variations," paper deliv- ered at the Eastman School of Music, March 1995. In the latter, interest centers around^ Variation 21, where the original Urlinie 3-2-1 in Bb major is now set as 5-4-3 in the relative minor key. A similar problem of Urlinie reinterpretation occurs in Brahms' Haydn Variations Op. -

Journal of the Conductors Guild

Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 2015-2016 19350 Magnolia Grove Square, #301 Leesburg, VA 20176 Phone: (646) 335-2032 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.conductorsguild.org Jan Wilson, Executive Director Officers John Farrer, President John Gordon Ross, Treasurer Erin Freeman, Vice-President David Leibowitz, Secretary Christopher Blair, President-Elect Gordon Johnson, Past President Board of Directors Ira Abrams Brian Dowdy Jon C. Mitchell Marc-André Bougie Thomas Gamboa Philip Morehead Wesley J. Broadnax Silas Nathaniel Huff Kevin Purcell Jonathan Caldwell David Itkin Dominique Royem Rubén Capriles John Koshak Markand Thakar Mark Crim Paul Manz Emily Threinen John Devlin Jeffery Meyer Julius Williams Advisory Council James Allen Anderson Adrian Gnam Larry Newland Pierre Boulez (in memoriam) Michael Griffith Harlan D. Parker Emily Freeman Brown Samuel Jones Donald Portnoy Michael Charry Tonu Kalam Barbara Schubert Sandra Dackow Wes Kenney Gunther Schuller (in memoriam) Harold Farberman Daniel Lewis Leonard Slatkin Max Rudolf Award Winners Herbert Blomstedt Gustav Meier Jonathan Sternberg David M. Epstein Otto-Werner Mueller Paul Vermel Donald Hunsberger Helmuth Rilling Daniel Lewis Gunther Schuller Thelma A. Robinson Award Winners Beatrice Jona Affron Carolyn Kuan Jamie Reeves Eric Bell Katherine Kilburn Laura Rexroth Miriam Burns Matilda Hofman Annunziata Tomaro Kevin Geraldi Octavio Más-Arocas Steven Martyn Zike Theodore Thomas Award Winners Claudio Abbado Frederick Fennell Robert Shaw Maurice Abravanel Bernard Haitink Leonard Slatkin Marin Alsop Margaret Hillis Esa-Pekka Salonen Leon Barzin James Levine Sir Georg Solti Leonard Bernstein Kurt Masur Michael Tilson Thomas Pierre Boulez Sir Simon Rattle David Zinman Sir Colin Davis Max Rudolf Journal of the Conductors Guild Volume 32 (2015-2016) Nathaniel F. -

MTO 15.2: Samarotto, Plays of Opposing Motion

Volume 15, Number 2, June 2009 Copyright © 2009 Society for Music Theory Frank Samarotto KEYWORDS: Schenker, Kurth, energetics, melodic analysis ABSTRACT: Rameau’s privileging of harmony over melody may be set against the pendulum swing of Kurth’s pure melodic energy. Although Schenker’s theory clearly identifies linear motion as governed by harmony, Schenker could still place great importance on melodic directionality and impulse as independent elements, even when they run counter to the harmonic setting or to the descending trajectory of the Urlinie. Extrapolating from Schenker’s work, this paper will examine what I call contra-structural melodic impulses, characterized by two aspects: directionality and ambitus, and acting as a compositionally significant counter pull to the tonal structure. Received October 2008 [1] Rameau’s seminal treatise of 1722 opens with a powerful declaration: the science of music is divided into melody and harmony, but, he says, . a knowledge of harmony is sufficient for a complete understanding of music (Rameau 1971, 3, editorial fn. 1). Indeed, an annotation in a contemporary copy adds that this makes a “remarkable statement: harmony and melody are inseparable” (Rameau 1971). It is a remarkable statement, especially when understood in light of Rameau’s progression of the fundamental bass, the progenitor of all later theories of harmony. Rameau’s cadence parfaite gathered together the contrapuntal threads of individual melodic lines and made them subordinates of, or at least co-conspirators with the root progression, which is a much more ideal concept.(1) Almost two centuries later, Ernst Kurth tried to detach melody entirely from harmony, hearing in Bach’s melodic lines an unbridled energy, careening about unrestrained by the bounds of harmony (Kurth 1917).