Paris / Ojibwa by Robert Houle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

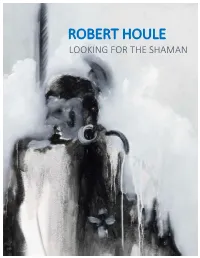

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

Concepts of Spirituality in 'Th Works of Robert Houle and Otto Rogers Wxth Special Consideration to Images of the Land

CONCEPTS OF SPIRITUALITY IN 'TH WORKS OF ROBERT HOULE AND OTTO ROGERS WXTH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO IMAGES OF THE LAND Nooshfar B, Ahan, BCom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial filfillment of the requïrements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 6 December 2000 O 2000, Nooshfar B. Ahan Bibliothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibIiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada your me voue rélèreoca Our file Notre reMrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfomq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis examines the use of landscape motifs by two contemporary Canadian artists to express their spiritual aspirations. Both Robert Houle and Otto Rogers, inspired by the Canadian prairie landscape, employ its abstracted form to convey their respective spiritual ideas. -

Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice by Jonathan A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OCAD University Open Research Repository Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice By Jonathan A. Lockyer A thesis presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts, 2014 Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University Toronto, Ontario Canada, April 2014 ©Jonathan A. Lockyer, April 2014 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature __________________________________________________ ii Abstract Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice Masters of Fine Arts, 2014 Jonathan A. Lockyer Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University This thesis establishes a critical genealogy of the history of curating Indigenous art in Canada from an Ontario-centric perspective. Since the pivotal intervention by Indigenous artists, curators, and political activists in the staging of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, Quebec, the curation of Indigenous art in Canada has moved from a practice of necessity, largely unrecognized by mainstream arts institutions, to a professionalized practice that exists both within and on the margins of public galleries. -

ROSALIE FAVELL | Www

ROSALIE FAVELL www.rosaliefavell.com | www.wrappedinculture.ca EDUCATION PhD (ABD) Cultural Mediations, Institute for Comparative Studies in Art, Literature and Culture, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (2005 to 2009) Master of Fine Arts, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States (1998) Bachelor of Applied Arts in Photographic Arts, Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (1984) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Rosalie Favell: Shifting Focus, Latcham Art Centre, Stoufville, Ontario, Canada. (October 20 – December 8) 2018 Facing the Camera, Station Art Centre, Whitby, Ontario, Canada. (June 2 – July 8) 2017 Wish You Were Here, Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, M’Chigeeng, Ontario, Canada. (May 25 – August 7) 2016 from an early age revisited (1994, 2016), Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Regina, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. (July – September) 2015 Rosalie Favell: (Re)Facing the Camera, MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. (August 29 – November 22) 2014 Rosalie Favell: Relations, All My Relations, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. (December 12 – February 20, 2015) 2013 Muse as Memory: the Art of Rosalie Favell, Gallery of the College of Staten Island, New York City, New York, United States. (November 14 – December 19) 2013 Facing the Camera: Santa Fe Suite, Museum of Contemporary Native Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States. (May 25 – July 31) 2013 Rosalie Favell, Cube Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (April 2 – May 5) 2013 Wish You Were Here, Art Gallery of Algoma, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. (February 28 – May 26) 2012 Rosalie Favell Karsh Award Exhibition, Karsh Masson Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (September 7 – October 28) 2011 Rosalie Favell: Living Evidence, Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. -

Indian Art in the 1990S Ryan Rice

Document generated on 09/25/2021 9:32 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review Presence and Absence Redux: Indian Art in the 1990s Ryan Rice Continuities Between Eras: Indigenous Art Histories Article abstract Continuité entre les époques : histoires des arts autochtones Les années 1990 sont une décennie cruciale pour l’avancement et le Volume 42, Number 2, 2017 positionnement de l’art et de l’autonomie autochtones dans les récits dominants des états ayant subi la colonisation. Cet article reprend l’exposé des URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042945ar faits de cette période avec des détails fort nécessaires. Pensé comme une DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1042945ar historiographie, il propose d’explorer chronologiquement comment les conservateurs et les artistes autochtones, et leurs alliés, ont répondu et réagi à des moments clés des mesures coloniales et les interventions qu’elles ont See table of contents suscitées du point de vue politique, artistique, muséologique et du commissariat d’expositions. À la lumière du 150e anniversaire de la Confédération canadienne, et quinze ans après la présentation de la Publisher(s) communication originale au colloque, Mondialisation et postcolonialisme : Définitions de la culture visuelle , du Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, il UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des V reste urgent de faire une analyse critique des préoccupations contemporaines universités du Canada) plus vastes, relatives à la mise en contexte et à la réconciliation de l’histoire de l’art autochtone sous-représentée. ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rice, R. -

Art, Artist, and Witness(Ing) in Canada's Truth and Reconciliation

Dance with us as you can…: Art, Artist, and Witness(ing) in Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Journey by Jonathan Robert Dewar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Indigenous and Canadian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2017, Jonathan Robert Dewar Abstract This dissertation explores, through in-depth interviews, the perspectives of artists and curators with regard to the question of the roles of art and artist – and the themes of community, responsibility, and practice – in truth, healing, and reconciliation during the early through late stages of the 2008-2015 mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), as its National Events, statement taking, and other programming began to play out across the country. The author presents the findings from these interviews alongside observations drawn from the unique positioning afforded to him through his professional work in healing and reconciliation-focused education and research roles at the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2007-2012) and the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre (2012-2016) about the ways art and artists were invoked and involved in the work of the TRC, alongside it, and/or in response to it. A chapter exploring Indigenous writing and reconciliation, with reference to the work of Basil Johnston, Jeannette Armstrong, Tomson Highway, Maria Campbell, Richard Wagamese, and many others, leads into three additional case studies. The first explores the challenges of exhibiting the legacies of Residential Schools, focusing on Jeff Thomas’ seminal curatorial work on the archival photograph-based exhibition Where Are the Children? Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools and Heather Igloliorte’s curatorial work on the exhibition ‘We were so far away…’: The Inuit Experience of Residential Schools, itself a response to feedback on Where Are the Children? Both examinations draw extensively from the author’s interviews with the curators. -

Indigenous Sovereignty and Settler Amnesia: Robert Houle's Premises

Document generated on 10/02/2021 2:14 a.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review Indigenous Sovereignty and Settler Amnesia: Robert Houle’s Premises for Self Rule Stacy A. Ernst Continuities Between Eras: Indigenous Art Histories Article abstract Continuité entre les époques : histoires des arts autochtones Le modernisme en art est souvent considéré comme un développement Volume 42, Number 2, 2017 spécifiquement occidental. Robert Houle, l’artiste, écrivain et commissaire d’exposition d’origine Saulteaux, a cependant toujours soutenu que sa propre URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042950ar pratique est moderniste et qu’elle suit une filiation esthétique autochtone. Cet DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1042950ar article s’intéresse particulièrement à une oeuvre produite par Houle en 1994, Premises for Self Rule, dans laquelle l’artiste a juxtaposé des textes de législation coloniale à des panneaux peints en monochrome et des cartes See table of contents postales trouvées en archives. Il propose qu’à travers cette stratégie de rapprochement, l’artiste fusionne la tradition de la peinture de parflèche à l’esthétique moderniste, remettant ainsi en lumière la négociation Publisher(s) interculturelle, l’amnésie coloniale, ainsi que les écarts qui séparent les épistémologies et traditions artistiques des peuples autochtones et allochtones. UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Ernst, S. A. (2017). Indigenous Sovereignty and Settler Amnesia: Robert Houle’s Premises for Self Rule. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 42(2), 108–120. -

Robert Houle Paris/ Ojibwa

1970 Centre 40ème anniversaire culturel canadien 2010 Paris Press Release An installation by Robert Houle Paris/ Ojibwa April 13, 2010 from April 14 to September 10, 2010 Gallery talk around the installation project / 5:00 pm Robert Houle Mick Gidley / University of Leeds Donald Smith / University of Calgary Limited access Reservations : 01 44 43 21 49 Opening / 6:30 pm The Canadian Cultural Centre presents an installation by Robert Houle which travels back in time of 1845 in Paris. Paris/Ojibwa evokes an exotic contact with the Ojibwa which impressed the Parisian imagination in the 19th century and inspired painters and poets, among them Delacroix and Baudelaire. The installation was conceived in 2006 during the artist’s residency at La Cité des Arts in Paris. The work is an homage as well as a reflection on the theme of disappearance. The title of the work alludes to contact between Parisians and a group of indigenous people from Canada guided by a remarkable man, Maungwudaus (a Great Hero). From April to December of 1845, Parisians saw authentic Ojibwa on the streets as performers and always as a curiosity. These Ojibwa who were also called Mississauga or Chippewa, came from what was then known as Canada West. At the behest of painter George Catlin, Maungwudaus and his family and companions travelled to Paris to replace the Iowa, another aboriginal tribe, in the tableaux vivants that complemented the display of Catlin’s paintings in Paris. Catlin describes their arrival in Paris: “In the midst of my grief, with my little family around me, with my collection still open, and my lease for the Salle Valentino not yet expired, there suddenly arrived from London a party of eleven Ojibbeway Indians, from the region of Lake Huron, in Upper Canada, who had been brought to England by a Canadian, but Photography © Michael Cullen (detail) had since been under the management of a young man from the city of London. -

Robert Houle the Pines 2002 – 2004

Teacher Resource SUGGESTED GRADE LEVELS: Grade 7 – Grade 12 CURRICULUM LINKS: Visual Arts, Science, Geography, Social Studies ROBERT HOULE THE PINES 2002 – 2004 “The story of Canada is about us as well. From day one. Because we were here frst. We settled here frst. It’s a tripod, this country. It’s French, English and First Nations. We helped shape this country, you know, and we continue to.” —Robert Houle Robert Houle, The Pines, 2002–2004. Oil on canvas, panel (centre): 91.4 x 121.9 cm., panel (side, each of two): 91.4 x 91.4 cm. © Robert Houle. GUIDED OBSERVATION • How would you describe the feeling of this artwork? What makes you say that? • The Pines are made of three separate canvases. Why do you think the artist decided to separate the pieces? • If you could ask the artist one question about this work, what would it be? CONTEXT Robert Houle made this work after visiting the Pines, a burial ground and recreation area in Kanehsata:ke, a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) settlement near Oka, Quebec. It was the site of an ongoing land dispute. The Kanien’kehá:ka community asserted King Louis XV of France and gave the land to the Sulpician order of priests in the 1700s, for the beneft of the Kanien’kehá:ka and Algonquin communities in the area. The Sulpicians sold of much of that land to European settlers. Teacher Resource continued CONTEXT In 1990, the Pines area became the site of a tense 78-day standof between Canadian armed forces and Mohawk Warriors and Land Defenders from across Canada. -

Robert Houle Art for Mourning and a Call for Change

ART CANADA INSTITUTE INSTITUT DE L’ART CANADIEN JULY 2, 2021 ROBERT HOULE ART FOR MOURNING AND A CALL FOR CHANGE Saulteaux artist and curator Robert Houle has played a crucial role in initiating discussions about political and cultural issues surrounding First Nations peoples. At a time of mourning and urgent need for change, his art has particular poignance, encouraging a renewed vision of the world. Robert Houle, O-Ween Du Muh Waun (We Were Told), 2017, Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Charlottetown. Between the mid 1800s and 1996, Canada removed 150,000 Indigenous children, under duress, from their families and forced them to attend government-funded, assimilation institutions known as residential schools. The internationally recognized Saulteaux artist and curator Robert Houle (b.1947) was one of those children. In 2018 the Art Canada Institute was honoured to publish a book by Shirley Madill about this revered Manitoba- born leader in the arts. Houle’s work confronts colonialism by challenging it, undermining it, and asking us, “Who tells the stories of the land and the people who live here?” His art educates and advocates, and it explores the Indigenous experience. With this week’s newsletter we’re sharing excerpts from Robert Houle: Life & Work that reveal how the artist asks us to consider fundamental questions about our country, acknowledge the most painful parts of our history, and contemplate what this means for our present and our future. Sara Angel Founder and Executive Director, Art Canada Institute Support is available for anyone affected by the effects of residential school through the national Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

WHAT IS WRONG WITH THIS PICTURE?: INDIGENOUS ARTISTS CONTEST THE "PLACE" OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLE IN CANADA By Paula E. Loh A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada May, 2015 Copyright © Paula E. Loh, 2015 "We see the world, not as it is, but as we are." ~ Stephen R. Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People ii Abstract Indigenous artists challenge cultural stereotypes by creating images that contest preconceived notions of the "place" of Indigenous people held by the Canadian population at large. This thesis research explores the question of identity and stereotypes and how this is transgressed through the work of contemporary Indigenous artists in Canada to adjust the position of Indigenous people in the social hierarchy that controls their "place." Many Indigenous artists incorporate political statements into their artworks that challenge the ongoing stereotypes that assign Indigenous people to their "place"; the political commentary is often the only aspect of their work that identifies it as "Indigenous," with a variety of techniques, media, and styles used in the creation of the art, reflecting the individuality of the artists. The normativity of whiteness and its impact on ideology and politics is examined, both in historical and contemporary times. Hegemonic images have promoted the Eurocentric concept that the White "race" is the norm and the standard by which others should be judged and put in their "place," contributing to the objectification of Indigenous peoples and the creation of the stereotypical "Indian," such as the "noble savage," and the "ignoble savage." Images created by contemporary Indigenous artists transgress these cultural stereotypes. -

Houle November 2013 CV

Robert Houle 1 Education 1975 McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Bachelor of Education (Art Education) 1972 Salzburg International Summer Academy, Drawing and Painting 1972 University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Bachelor of Arts (Art History) Selected Solo Exhibitions 2013 Galerie Nicolas Robert, Montreal, Quebec. 2013 1 Bedford Condo Project, Toronto, Ontario 2012 Art Gallery of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario 2012 University of Manitoba School of Art Gallery, Winnipeg, Manitoba 2011 Galerie Nicolas Robert, Montreal, Quebec. 2011 Art Gallery of Peterborough, Peterborough, Ontario 2010 Canadian Cultural Centre, Paris, France 2010 Orenda Art International, Paris, France 2008 Smart Art Project #3, Toronto, Ontario 2007 McMaster Museum of Art, Hamilton, Ontario 2007 McLaughlin Art Gallery, Oshawa, Ontario 2006 Urban Shaman, Winnipeg, Manitoba 2001 MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan 2001 Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston, Ontario 2000 Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario 2000 Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan 2000 Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, Toronto, Ontario 1999 Winnipeg Art Gallery, Winnipeg Manitoba 1996 Garnet Press Gallery, Toronto, Ontario 1994 Garnet Press Gallery, Toronto, Ontario 1993 Carleton University Art Gallery, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario 1993 Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario 1992 YYZ, Toronto, Ontario 1992 Articule, Montreal, Quebec 1991 Mackenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan 1991 Hood College, Frederick, Maryland 1991 Glenbow - Alberta Institute, Calgary,