DECOLONIZATION Through the Art of ROBERT HOULE DECOLONIZATION Through the Art of ROBERT HOULE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

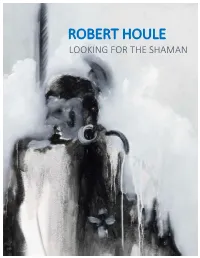

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

Concepts of Spirituality in 'Th Works of Robert Houle and Otto Rogers Wxth Special Consideration to Images of the Land

CONCEPTS OF SPIRITUALITY IN 'TH WORKS OF ROBERT HOULE AND OTTO ROGERS WXTH SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO IMAGES OF THE LAND Nooshfar B, Ahan, BCom A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial filfillment of the requïrements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 6 December 2000 O 2000, Nooshfar B. Ahan Bibliothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibIiographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada your me voue rélèreoca Our file Notre reMrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfomq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis examines the use of landscape motifs by two contemporary Canadian artists to express their spiritual aspirations. Both Robert Houle and Otto Rogers, inspired by the Canadian prairie landscape, employ its abstracted form to convey their respective spiritual ideas. -

Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism

Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism Michel Delville is a writer and musician living in Liège, Belgium. He is the author of several books including J.G. Ballard and The American Prose Poem, which won the 1998 SAMLA Studies Book Award. He teaches English and American literatures, as well as comparative literatures, at the University of Liège, where he directs the Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Poetics. He has been playing and composing music since the mid-eighties. His most recently formed rock-jazz band, the Wrong Object, plays the music of Frank Zappa and a few tunes of their own (http://www.wrongobject.be.tf). Andrew Norris is a writer and musician resident in Brussels. He has worked with a number of groups as vocalist and guitarist and has a special weakness for the interface between avant garde poetry and the blues. He teaches English and translation studies in Brussels and is currently writing a book on post-epiphanic style in James Joyce. Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism Michel Delville and Andrew Norris Cambridge published by salt publishing PO Box 937, Great Wilbraham PDO, Cambridge cb1 5jx United Kingdom All rights reserved © Michel Delville and Andrew Norris, 2005 The right of Michel Delville and Andrew Norris to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing. -

Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice by Jonathan A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OCAD University Open Research Repository Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice By Jonathan A. Lockyer A thesis presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts, 2014 Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University Toronto, Ontario Canada, April 2014 ©Jonathan A. Lockyer, April 2014 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Signature __________________________________________________ ii Abstract Charting the Development of Indigenous Curatorial Practice Masters of Fine Arts, 2014 Jonathan A. Lockyer Criticism and Curatorial Practice OCAD University This thesis establishes a critical genealogy of the history of curating Indigenous art in Canada from an Ontario-centric perspective. Since the pivotal intervention by Indigenous artists, curators, and political activists in the staging of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, Quebec, the curation of Indigenous art in Canada has moved from a practice of necessity, largely unrecognized by mainstream arts institutions, to a professionalized practice that exists both within and on the margins of public galleries. -

Get Smart with Art Is Made Possible with Support from the William K

From the Headlines About the Artist From the Artist Based on the critics’ comments, what aspects of Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) is Germany in 1830, Albert Bierstadt Bierstadt’s paintings defined his popularity? best known for capturing majestic moved to Massachusetts when he western landscapes with his was a year old. He demonstrated an paintings of awe-inspiring mountain early interest in art and at the age The striking merit of Bierstadt in his treatment of ranges, vast canyons, and tumbling of twenty-one had his first exhibit Yosemite, as of other western landscapes, lies in his waterfalls. The sheer physical at the New England Art Union in power of grasping distances, handling wide spaces, beauty of the newly explored West Boston. After spending several years truthfully massing huge objects, and realizing splendid is evident in his paintings. Born in studying in Germany at the German atmospheric effects. The success with which he does Art Academy in Düsseldorf, Bierstadt this, and so reproduces the noblest aspects of grand returned to the United States. ALBERT BIERSTADT scenery, filling the mind of the spectator with the very (1830–1902) sentiment of the original, is the proof of his genius. A great adventurer with a pioneering California Spring, 1875 Oil on canvas, 54¼ x 84¼ in. There are others who are more literal, who realize details spirit, Bierstadt joined Frederick W. Lander’s Military Expeditionary Presented to the City and County of more carefully, who paint figures and animals better, San Francisco by Gordon Blanding force, traveling west on the overland who finish more smoothly; but none except Church, and 1941.6 he in a different manner, is so happy as Bierstadt in the wagon route from Saint Joseph, Watkins Yosemite Art Gallery, San Francisco. -

ROSALIE FAVELL | Www

ROSALIE FAVELL www.rosaliefavell.com | www.wrappedinculture.ca EDUCATION PhD (ABD) Cultural Mediations, Institute for Comparative Studies in Art, Literature and Culture, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (2005 to 2009) Master of Fine Arts, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States (1998) Bachelor of Applied Arts in Photographic Arts, Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (1984) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Rosalie Favell: Shifting Focus, Latcham Art Centre, Stoufville, Ontario, Canada. (October 20 – December 8) 2018 Facing the Camera, Station Art Centre, Whitby, Ontario, Canada. (June 2 – July 8) 2017 Wish You Were Here, Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, M’Chigeeng, Ontario, Canada. (May 25 – August 7) 2016 from an early age revisited (1994, 2016), Wanuskewin Heritage Park, Regina, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. (July – September) 2015 Rosalie Favell: (Re)Facing the Camera, MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. (August 29 – November 22) 2014 Rosalie Favell: Relations, All My Relations, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. (December 12 – February 20, 2015) 2013 Muse as Memory: the Art of Rosalie Favell, Gallery of the College of Staten Island, New York City, New York, United States. (November 14 – December 19) 2013 Facing the Camera: Santa Fe Suite, Museum of Contemporary Native Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States. (May 25 – July 31) 2013 Rosalie Favell, Cube Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (April 2 – May 5) 2013 Wish You Were Here, Art Gallery of Algoma, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. (February 28 – May 26) 2012 Rosalie Favell Karsh Award Exhibition, Karsh Masson Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (September 7 – October 28) 2011 Rosalie Favell: Living Evidence, Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. -

Indian Art in the 1990S Ryan Rice

Document generated on 09/25/2021 9:32 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review Presence and Absence Redux: Indian Art in the 1990s Ryan Rice Continuities Between Eras: Indigenous Art Histories Article abstract Continuité entre les époques : histoires des arts autochtones Les années 1990 sont une décennie cruciale pour l’avancement et le Volume 42, Number 2, 2017 positionnement de l’art et de l’autonomie autochtones dans les récits dominants des états ayant subi la colonisation. Cet article reprend l’exposé des URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042945ar faits de cette période avec des détails fort nécessaires. Pensé comme une DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1042945ar historiographie, il propose d’explorer chronologiquement comment les conservateurs et les artistes autochtones, et leurs alliés, ont répondu et réagi à des moments clés des mesures coloniales et les interventions qu’elles ont See table of contents suscitées du point de vue politique, artistique, muséologique et du commissariat d’expositions. À la lumière du 150e anniversaire de la Confédération canadienne, et quinze ans après la présentation de la Publisher(s) communication originale au colloque, Mondialisation et postcolonialisme : Définitions de la culture visuelle , du Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, il UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des V reste urgent de faire une analyse critique des préoccupations contemporaines universités du Canada) plus vastes, relatives à la mise en contexte et à la réconciliation de l’histoire de l’art autochtone sous-représentée. ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rice, R. -

Kansas City, Missouri

Forty-Fourth Annual Conference Hosted by University of Missouri-Kansas City InterContinental Kansas City at the Plaza 28 February–4 March 2018 Kansas City, Missouri Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), the early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. Each member lists current topics or projects that are then indexed, providing a useful means of contact for those with shared interests. -

Concrete Poetry : the Influence of Design and Marketing on Aesthetics

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1985 Concrete poetry : the influence of design and marketing on aesthetics Tineke Bierma Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Poetry Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bierma, Tineke, "Concrete poetry : the influence of design and marketing on aesthetics" (1985). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3438. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5321 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Tineke Bierma for the Master of Arts in German presented November 21, 1985. Title: Concrete Poetry: The Influence of Design and Marketing on Aesthetics. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Linda B. Parshall Thomas Buell This thesis exp lores the past and present of concrete poetry with the purpose of finding out whether concrete poetry is stm being produced in its original form, or whether it has changed. Concrete poets were not the first ones to create picture poems and similar texts. In chapter I an overview of earlier picture poetry is given. It and other precursors of concrete poetry are discussed and their possible contributions evaluated. Chapters 11 and 111 dea1 with the definition of concrete poetry of the mid-fifties and sixties ( pure, classic c.p.). -

A Group Psychoeducational/Art

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE THE ART OF BEING SPIRITED: A GROUP PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL/ART THERAPY GUIDE FOR USE WITH ADOLESCENTS WITH EATING DISORDERS BY ELIZABETH MAY YOUNG MCKENNA A Final Project submitted to the Campus Alberta Applied Psychology: Counseling Initiative in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF COUNSELING Alberta (November) (2005) All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or part by photocopy or other means without permission of the author. ii iii ABSTRACT This project is a guide that combines spiritual, cognitive, creative, expressive and experiential elements into a group process to help health care professionals support adolescents with an eating disorder. The process embraces a holistic approach towards therapeutic interventions that incorporates Eastern and Western philosophies towards healing and art history with cross cultural links to develop the critical being through mindfulness practice, consciousness raising and communal experiential processes. Literature reviews on spirituality, eating disorders, art therapy, creativity, critical thinking, self and group process identify themes, topics and strategies which form the foundation for interventions. Theoretical underpinnings, ethic of care, suggested topics, format for sessions, psychoeducational material for facilitators and participants, and ways to evaluate the product, process and facilitator are included. iv DEDICATION To my husband for his love, fidelity, acerbic wit, sense of humour and unwavering support and encouragement. To my children Nairn, Noel and Kirsty who have taught me the most of what I know about adolescents, and forced me to embrace change. To my siblings for providing a good model for what it means to be a family. -

Art, Artist, and Witness(Ing) in Canada's Truth and Reconciliation

Dance with us as you can…: Art, Artist, and Witness(ing) in Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Journey by Jonathan Robert Dewar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Indigenous and Canadian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2017, Jonathan Robert Dewar Abstract This dissertation explores, through in-depth interviews, the perspectives of artists and curators with regard to the question of the roles of art and artist – and the themes of community, responsibility, and practice – in truth, healing, and reconciliation during the early through late stages of the 2008-2015 mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), as its National Events, statement taking, and other programming began to play out across the country. The author presents the findings from these interviews alongside observations drawn from the unique positioning afforded to him through his professional work in healing and reconciliation-focused education and research roles at the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2007-2012) and the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre (2012-2016) about the ways art and artists were invoked and involved in the work of the TRC, alongside it, and/or in response to it. A chapter exploring Indigenous writing and reconciliation, with reference to the work of Basil Johnston, Jeannette Armstrong, Tomson Highway, Maria Campbell, Richard Wagamese, and many others, leads into three additional case studies. The first explores the challenges of exhibiting the legacies of Residential Schools, focusing on Jeff Thomas’ seminal curatorial work on the archival photograph-based exhibition Where Are the Children? Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools and Heather Igloliorte’s curatorial work on the exhibition ‘We were so far away…’: The Inuit Experience of Residential Schools, itself a response to feedback on Where Are the Children? Both examinations draw extensively from the author’s interviews with the curators. -

An Analysis of the Artistry of Black Women in the Black Arts Movement, 1960S-1980S Abney Louis Henderson University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-10-2014 Four Women: An Analysis of the Artistry of Black Women in the Black Arts Movement, 1960s-1980s Abney Louis Henderson University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Henderson, Abney Louis, "Four Women: An Analysis of the Artistry of Black Women in the Black Arts Movement, 1960s-1980s" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Four Women: An Analysis of the Artistry and Activism of Black Women in the Black Arts Movement, 1960’s–1980’s by Abney L. Henderson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts with a concentration in Africana Studies Department of Africana Studies College of Art and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Cheryl Rodriquez, Ph.D. Kersuze Simeon-Jones, Ph.D. Navita Cummings James, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 10, 2014 Keywords: Black Revolution, Cultural Identity, Creative Expression, Black Female Aesthetics Copyright © 2014, Abney L. Henderson DEDICATION “Listen to yourself and in that quietude you might hear the voice of God.” -Dr. Maya Angelou April 4,1928-May 28, 2014 For my mother, Germaine L.