By the End of the Film One Feels Him to Be Not Only a Vi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS the INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION of Browse Through the Complete Unitel Catalogue of More Than 2,000 Titles At

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS THE INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION OF Browse through the complete Unitel catalogue of more than 2,000 titles at www.unitel.de Date: March 2018 FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CONTENT BRITTEN: GLORIANA Susan Bullock/Toby Spence/Kate Royal/Peter Coleman-Wright Conducted by: Paul Daniel OPERAS 3 Staged by: Richard Jones BALLETS 8 Cat. No. A02050015 | Length: 164' | Year: 2016 DONIZETTI: LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT Natalie Dessay/Juan Diego Flórez/Felicity Palmer Conducted by: Bruno Campanella Staged by: Laurent Pelly Cat. No. A02050065 | Length: 131' | Year: 2016 OPERAS BELLINI: NORMA Sonya Yoncheva/Joseph Calleja/Sonia Ganassi/ Brindley Sherratt/La Fura dels Baus Conducted by: Antonio Pappano Staged by: Àlex Ollé Cat. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

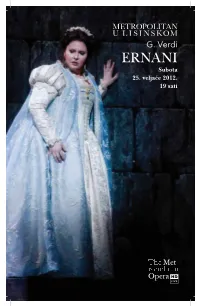

ERNANI Web.Pdf

Foto: Metropolitan opera G. Verdi ERNANI Subota, 25. veljae 2012., 19 sati THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Giuseppe Verdi ERNANI Opera u etiri ina Libreto: Francesco Maria Piave prema drami Hernani Victora Hugoa SUBOTA, 25. VELJAČE 2012. POČETAK U 19 SATI. Praizvedba: Teatro La Fenice u Veneciji, 9. ožujka 1844. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 18. studenoga 1871. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 28. siječnja 1903. Premijera ove izvedbe: 18. studenoga 1983. ERNANI Marcello Giordani JAGO Jeremy Galyon DON CARLO, BUDUĆI CARLO V. Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana Dmitrij Hvorostovsky ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo DON RUY GOMEZ DE SILVA DIRIGENT Marco Armiliato Ferruccio Furlanetto REDATELJ I SCENOGRAF ELVIRA Angela Meade Pier Luigi Samaritani GIOVANNA Mary Ann McCormick KOSTIMOGRAF Peter J. Hall DON RICCARDO OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE Gil Wechsler Adam Laurence Herskowitz SCENSKA POSTAVA Peter McClintock Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Radnja se događa u Španjolskoj 1519. godine. Stanka nakon prvoga i drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 22 sata i 50 minuta. Tekst: talijanski. Titlovi: engleski. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: PRVI IN - IL BANDITO (“Mercè, diletti amici… Come rugiada al ODMETNIK cespite… Oh tu che l’ alma adora”). Otac Don Carlosa, u operi Don Carla, Druga slika dogaa se u Elvirinim odajama u budueg Carla V., Filip Lijepi, dao je Silvinu dvorcu. Užasnuta moguim brakom smaknuti vojvodu od Segovije, oduzevši sa Silvom, Elvira eka voljenog Ernanija da mu imovinu i prognavši obitelj. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Guillaume Tell Guillaume

1 TEATRO MASSIMO TEATRO GIOACHINO ROSSINI GIOACHINO | GUILLAUME TELL GUILLAUME Gioachino Rossini GUILLAUME TELL Membro di seguici su: STAGIONE teatromassimo.it Piazza Verdi - 90138 Palermo OPERE E BALLETTI ISBN: 978-88-98389-66-7 euro 10,00 STAGIONE OPERE E BALLETTI SOCI FONDATORI PARTNER PRIVATI REGIONE SICILIANA ASSESSORATO AL TURISMO SPORT E SPETTACOLI ALBO DEI DONATORI FONDAZIONE ART BONUS TEATRO MASSIMO TASCA D’ALMERITA Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente Oscar Pizzo Direttore artistico ANGELO MORETTINO SRL Gabriele Ferro Direttore musicale SAIS AUTOLINEE CONSIGLIO DI INDIRIZZO Leoluca Orlando (sindaco di Palermo) AGOSTINO RANDAZZO Presidente Leonardo Di Franco Vicepresidente DELL’OGLIO Daniele Ficola Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente FILIPPONE ASSICURAZIONE Enrico Maccarone GIUSEPPE DI PASQUALE Anna Sica ALESSANDRA GIURINTANO DI MARCO COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI Maurizio Graffeo Presidente ISTITUTO CLINICO LOCOROTONDO Marco Piepoli Gianpiero Tulelli TURNI GUILLAUME TELL Opéra en quatre actes (opera in quattro atti) Libretto di Victor Joseph Etienne De Jouy e Hippolyte Louis Florent Bis Musica di Gioachino Rossini Prima rappresentazione Parigi, Théâtre de l’Academie Royale de Musique, 3 agosto 1829 Edizione critica della partitura edita dalla Fondazione Rossini di Pesaro in collaborazione con Casa Ricordi di Milano Data Turno Ora a cura di M. Elizabeth C. Bartlet Sabato 20 gennaio Anteprima Giovani 17.30 Martedì 23 gennaio Prime 19.30 In occasione dei 150 anni dalla morte di Gioachino Rossini Giovedì 25 gennaio B 18.30 Sabato 27 gennaio -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Eleonora Buratto, from Mantua, Is One of the Most Highly Acclaimed Lyric Sopranos in the World

Saverio Clemente Andrea De Amici Luca Targetti Eleonora Buratto, from Mantua, is one of the most highly acclaimed lyric sopranos in the world. Her career began in 2009 singing as Creusa in Demofoonte, conducted by Riccardo Muti at the Salzburg Festival, Opéra Garnier and the Ravenna Festival. In the years that followed she sang under Maestro Muti as Susanna in the opera I Due Figaro by Mercadante, as Norina in Don Pasquale, Amelia in Simon Boccanegra, Alice in Falstaff and Countess Almaviva in Le Nozze di Figaro. At the start of 2015 she was Corinna at the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam in Il Viaggio a Reims, directed by Damiano Michieletto and conducted by Stefano Montanari. Since then her international career has continued to develop. That same year she sang for the first time both as Liù and as Countess Almaviva and she also inaugurated the Teatro San Carlo season in Naples singing as Micaela in Carmen conducted by Zubin Mehta. Since 2016 she has made other debuts which have become signature roles in her Eleonora Buratto repertoire such as Mimì at the Liceu in Barcelona, Donna Anna at Soprano the Aix-en-Provence Festival, Elettra in Idomeneo at the Teatro Real in Madrid (available worldwide from spring 2020 on Dvd and Bd by Opus Arte) and Luisa Miller once again at the Liceu. She has regularly made her return, amongst other theatres, to the Teatro Real in Madrid, Liceu in Barcelona, Lyric Opera in Chicago, Dutch National Opera, Teatro San Carlo in Naples, the Metropolitan Opera and the Royal Opera House and has sung in concert performances -

Damiano Michieletto Had Quickly Emerged to the International Scene As One of the Most Interesting Representatives of the Youngest Generation of Italian Directors

Saverio Clemente Andrea De Amici Luca Targetti Damiano Michieletto had quickly emerged to the international scene as one of the most interesting representatives of the youngest generation of Italian directors. He followed the direction course at School of Dramatic Arts “Paolo Grassi” in Milan and also graduated in Modern Letters at university of Venice, his home town. His production of Jaromír Weinberger’s Švanda Dudák at the 2003 Wexford Festival, acclaimed by the critics, wins the Irish Times ESB/Irish Theatre Award. Among the others, he stages L’italiana in Algeri at Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, La gazza ladra at Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro, in co- production with Teatro Comunale in Bologna and Fondazione Arena di Verona (it wins the 2008 Franco Abbiati Award), Lucia di Lammermoor, Il Corsaro, Luisa Miller and Poliuto at the Zürich Opernhaus, Roméo et Juliette and the Mozart/Da Ponte trilogy at Teatro La Fenice in Venice, Die Entführung aus dem Serail at Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, La scala di seta at the Rossini Opera Festival and at La Scala in Milan, Il barbiere di Siviglia at Grand Théâtre de Genève, Madama Butterfly in Turin, L’elisir d’amore in Valencia, Graz and Madrid, Martinů’s The Greek Passion in Palermo, Così fan tutte at the New National Theatre in Tokyo, Il Trittico at the Theater an der Wien and the Damiano Royal Opera in Copenhagen, Un ballo in maschera at La Scala, Michieletto Idomeneo at Theater an der Wien and The Rake’s Progress at Leipzig Opera and Teatro La Fenice. -

Ariadne Auf Naxos Soile Isokoski ∙ Sophie Koch Jochen Schmeckenbecher ∙ Johan Botha

RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNE AUF NaXOS SOILE ISOKOSKI ∙ SOPHIE KoCH JOCHEN SCHMECKENBECHER ∙ JOHAN BOTHA ORCHESTER DER WIENER STAATSOPER conducted by CHRISTIAN THIELEMANN staged by SVEN-ERIC BECHTOLF WIENER STAATSOPER RICHARD STRAUSS ARIADNE AUF NaXOS Orchestra Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper Here is one of the truly overwhelming successes in recent opera Conductor Christian Thielemann history: Christian Thielemann’s sensational return to the Vienna State Stage Director Sven-Eric Bechtolf Opera to conduct his first-ever performances there of Richard Strauss, with an ideal cast in an acclaimed production of Ariadne auf Naxos. “A triumph [...] world stars and ensemble shine” (Die Presse). “Strauss Primadonna (Ariadne) Soile Isokoski in all his glory”(Wiener Zeitung). “Festival standard [...] electrifying The Composer Sophie Koch excitement” (Kronen Zeitung). A Music Teacher Jochen Schmeckenbecher The Tenor (Bacchus) Johan Botha Director Sven-Erich Bechtolf “has again delved deeply into music Zerbinetta Daniela Fally and text”, observed the opera magazine Opernnetz in its rave review Harlequin Adam Plachetka of the performance captured here. “In Rolf Glittenberg’s beautiful Scaramuccio Carlos Osuna Jugendstil salon, he is constantly in touch with the heartbeat of the Truffaldin Jongmin Park story [...] For Bechtolf it is the subtle development of the characters Brighella Benjamin Bruns and their relationships with each other, as well as the work’s delicate The Dancing Master Norbert Ernst irony, that remain of paramount importance. As Ariadne, Soile Isokoski radiates enchanting vocal beauty as she forms endless nuances in one The Major-Domo Peter Matić blossoming phrase after another. Daniela Fally sings the gruellingly Lackey Marcus Pelz difficult part of Zerbinetta with great flexibility, acting it with nonchalant A Wigmaker Won Cheol Song coquettishness. -

National-Council-Auditions-Grand-Finals-Concert.Pdf

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Bertrand de Billy National Council Auditions host and guest artist Grand Finals Concert Joyce DiDonato Sunday, April 29, 2018 guest artist 3:00 PM Bryan Hymel Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2017–18 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Bertrand de Billy host and guest artist Joyce DiDonato guest artist Bryan Hymel “Martern aller Arten” from Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Mozart) Emily Misch, Soprano “Tacea la notte placida ... Di tale amor” from Il Trovatore (Verdi) Jessica Faselt, Soprano “Va! laisse couler mes larmes” from Werther (Massenet) Megan Grey, Mezzo-Soprano “Cruda sorte!” from L’Italiana in Algeri (Rossini) Hongni Wu, Mezzo-Soprano “In quali eccessi ... Mi tradì” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Today’s concert is Danielle Beckvermit, Soprano being recorded for “Amour, viens rendre à mon âme” from future broadcast Orphée et Eurydice (Gluck) over many public Ashley Dixon, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Gualtier Maldè! ... Caro nome” from Rigoletto (Verdi) local listings. Madison Leonard, Soprano Sunday, April 29, 2018, 3:00PM “O ma lyre immortelle” from Sapho (Gounod) Gretchen Krupp, Mezzo-Soprano “Sì, ritrovarla io giuro” from La Cenerentola (Rossini) Carlos Enrique Santelli, Tenor Intermission “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Jessica Faselt, Soprano “Down you go” (Controller’s Aria) from Flight (Jonathan Dove) Emily Misch, Soprano “Sein wir wieder gut” from Ariadne auf Naxos (R. Strauss) Megan Grey, Mezzo-Soprano “Wie du warst! Wie du bist!” from Der Rosenkavalier (R. -

Salzburg-Falstaff-2013.Pdf

LEADING TEAM ZUR INSZENIERUNG „Ich mache keine Opera buffa, sondern stelle einen Typen dar. Mein Falstaff ist nicht nur derjenige, der in den Lustigen Weibern von Windsor von Shakespeare vorkommt, wo er bloß ein Narr ist und sich von den Zubin Mehta, Musikalische Leitung Frauen betrügen lässt, sondern auch so, wie er unter den beiden Heinrichs [d. h. in den beiden Teilen von Damiano Michieletto, Regie Shakespeares Henry IV] war.“ Verdis Bemerkung, von Italo Pizzi in seinen Memorie verdiane (1901) überliefert, gibt bündig wieder, worum es dem Komponisten in seiner letzten Oper Falstaff ging: nicht um Paolo Fantin, Bühne die Wiederbelebung einer lustigen oder lächerlichen Figur in der Tradition der alten italienischen Buffa- Oper, sondern – wie sollte es beim großen Humanisten Verdi anders sein? – um das Porträt eines Carla Teti, Kostüme menschlichen Charakters in allen seinen Schattierungen. Arrigo Boito, dem Verdi seit der Otello-Premiere Alessandro Carletti, Licht zunehmend freundschaftlich verbunden war, wusste glücklicherweise recht genau, was für ein Libretto nötig war, um den bald 80-Jährigen zu einer weiteren gemeinsamen Arbeit zu motivieren. So ist es vor allem sein rocafilm, Video Verdienst, dass sich Verdi den jahrzehntelang gehegten Wunsch, eine komische Oper zu komponieren, doch noch erfüllen konnte. „Boito hat mir eine lyrische Komödie geschrieben, die keiner anderen gleicht“, Christian Arseni, Dramaturgie berichtete er 1890 in einem Brief. Auch wenn die Oper, die am 9. Februar 1893 an der Mailänder Scala ihre Walter Zeh, Choreinstudierung Uraufführung erlebte, eine gewisse Portion an konventioneller Situationskomik enthält, so ist sie doch vor allem eine Charakterkomödie – mit Musik, die in der Zeichnung der Figuren virtuos zwischen innerer Anteilnahme und ironischer Distanz changiert.