Remembering the Forgotten, Archaeology at the Morrissey WW1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Biking Guide

SUGGESTED ITINERARIES QUICK TIP: Ride your bike before 10 a.m. and after 5 p.m. to avoid traffic congestion. ARK JASPER NATIONAL P SHORT RIDES HALF DAY PYRAMID LAKE (MAP A) - Take the beautiful ride THE FALLS LOOP (MAP A) - Head south on the ROAD BIKING to Pyramid Lake with stunning views of Pyramid famous Icefields Parkway. Take a right onto the Mountain at the top. Distance: 14 km return. 93A and head for Athabasca Falls. Loop back north GUIDE Elevation gain: 100 m. onto Highway 93 and enjoy the views back home. Distance: 63 km return. Elevation gain: 210 m. WHISTLERS ROAD (MAP A) - Work up a sweat with a short but swift 8 km climb up to the base MARMOT ROAD (MAP A) - Head south on the of the Jasper Skytram. Go for a ride up the tram famous Icefields Parkway, take a right onto 93A and or just turn back and go for a quick rip down to head uphill until you reach the Marmot Road. Take a town. Distance: 16.5 km return. right up this road to the base of the ski hill then turn Elevation gain: 210 m. back and enjoy the cruise home. Distance: 38 km. Elevation gain: 603 m. FULL DAY MALIGNE ROAD (MAP A) - From town, head east on Highway 16 for the Moberly Bridge, then follow the signs for Maligne Lake Road. Gear down and get ready to roll 32 km to spectacular Maligne Lake. Once at the top, take in the view and prepare to turn back and rip home. -

WR 16Mar 1928 .Pdf

World -Radio, March 16, 1928. P n n rr rrr 1 itiol 111111 SPECIAL IRISHNUMBER Registered at the.G.P.O. Vol. VI.No. 138. as a Newspaper. FRIDAY. MARCH 16, 1928. Two Pence. WORLD -RADIO 8 tEMEN Station Identification Panel- Konigswusterhausen (Zeesen). Germany REC GE (Revised) Wavelength : 125o in. Frequency : 240 kc. Power :35 kw. H. T. BATTERY Approximate Distance from London : 575 miles. (Lea-melte Tide) Call " Achtung !Achtung !Hier die Deutsche Welle, Berlin,-Konigswus- terhausen."(Sometimes wavelength POSSESSES all the advantages of a DRY BATTERY given :" . auf Welle zwolf hun- dert and fiinfzig," when callre- -none of the disadvantages of the ordinary WET peated.)When relaying :" Ferner Ubertragimgauf "... (nameof BATTERY. relaying stations). Interval Signal:Metronome.Forty beats in ten seconds. 1. Perfectly noiseless, clean SpringConnections,no IntervalCall :" Achtung !Konigs. and reliable. 4.soldering. wusterhausen.DerVortragvon [name of lecturer]uber[titleof 5. No "creeping of salts. lecture]ist beendet.Auf Wieder- 2. Unspillable. Easily recharged, & main- 'toren in . Minuten."When 6. relaying :`& Auf Wiederhorenfur 3No attention required until tains full energy through- Konigswusterhausen in . exhausted. out the longest programme. Minuten ;fur Breslau and Gleiwitz [or as the case may be] nach eigenem Programm." 711,2 ails are null: in thefoll,n,ing three sizes: Own transmissionsandrelays.In eveningrelaysfromotherstations. H.T.1.Small ... 8d. each. Closes down at the same time as the relaying station. H.T.2.Large ... 10d. each. H.T.3.Extra Large 1:- each. (Copyright) A booklet containing alargenumberof these Guaranteed to give I a,volts per cell. panels canbeobtainedof B.B.C.Publications, Savoy Hrll, W. -

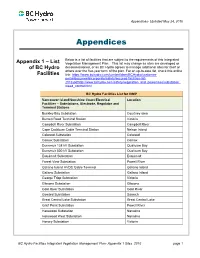

Appendices- Updated May 24, 2016

Appendices- Updated May 24, 2016 Appendices Below is a list of facilities that are subject to the requirements of this Integrated Appendix 1 – List Vegetation Management Plan. This list may change as sites are developed or of BC Hydro decommissioned, or as BC Hydro agrees to manage additional sites for itself or others over the five-year term of the plan. For an up-to-date list, check this online Facilities link: https://www.bchydro.com/content/dam/BCHydro/customer- portal/documents/corporate/safety/secured-facilities-list- 2013.pdfhttp://www.bchydro.com/safety/vegetation_and_powerlines/substation_ weed_control.html. BC Hydro Facilities List for IVMP Vancouver Island/Sunshine Coast Electrical Location Facilities – Substations, Electrode, Regulator and Terminal Stations Buckley Bay Substation Courtney area Burnett Road Terminal Station Victoria Campbell River Substation Campbell River Cape Cockburn Cable Terminal Station Nelson Island Colwood Substation Colwood Comox Substation Comox Dunsmuir 138 kV Substation Qualicum Bay Dunsmuir 500 kV Substation Qualicum Bay Esquimalt Substation Esquimalt Forest View Substation Powell River Galiano Island HVDC Cable Terminal Galiano Island Galiano Substation Galiano Island George Tripp Substation Victoria Gibsons Substation Gibsons Gold River Substation Gold River Goward Substation Saanich Great Central Lake Substation Great Central Lake Grief Point Substation Powell River Harewood Substation Nanaimo Harewood West Substation Nanaimo Horsey Substation Victoria BC Hydro Facilities Integrated Vegetation -

Contenido Estrenos Mexicanos

Contenido estrenos mexicanos ............................................................................120 programas especiales mexicanos .................................. 122 Foro de los Pueblos Indígenas 2019 .......................................... 122 Programa Exilio Español ....................................................................... 123 introducción ...........................................................................................................4 Programa Luis Buñuel ............................................................................. 128 Presentación ............................................................................................................... 5 El Día Después ................................................................................................ 132 ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! ................................................................................... 7 Feratum Film Festival .............................................................................. 134 Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura ....................................................8 ......... 10 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía funciones especiales mexicanas .......................................137 17° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia ............................11 programas especiales internacionales................148 ...........................................................................................................................12 jurados Programa Agnès Varda ...........................................................................148 -

Snow Survey and Water Supply Bulletin – January 1St, 2021

Snow Survey and Water Supply Bulletin – January 1st, 2021 The January 1st snow survey is now complete. Data from 58 manual snow courses and 86 automated snow weather stations around the province (collected by the Ministry of Environment Snow Survey Program, BC Hydro and partners), and climate data from Environment and Climate Change Canada and the provincial Climate Related Monitoring Program have been used to form the basis of the following report1. Weather October began with relatively warm and dry conditions, but a major cold spell dominated the province in mid-October. Temperatures primarily ranged from -1.5 to +1.0˚C compared to normal. The cold spell also produced early season low elevation snowfall for the Interior. Following the snowfall, heavy rain from an atmospheric river affected the Central Coast and spilled into the Cariboo, resulting in prolonged flood conditions. Overall, most of the Interior received above normal precipitation for the month, whereas coastal regions were closer to normal. In November, temperatures were steady at near normal to slightly above normal and primarily ranged from -0.5 to +1.5˚C through the province. The warmest temperatures relative to normal occurred in the Interior, while the coldest occurred in the Northwest. Precipitation was mostly below normal to near normal (35-105%) with the Northeast / Peace as the driest areas. A few locations, e.g. Prince Rupert and Williams Lake, were above 130% due to a strong storm event early in the month. Temperatures in December were relatively warm across the province, ranging from +1.0 to +5.0˚C above normal. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Tnemreie and RADIO REVIEW

TNeMreIe AND RADIO REVIEW VOLUME XXIII JULY 4th -DECEMBER 26th, 1928 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published from the Offices of " THE WIRELESS WORLD " ILIFFE & SONS LTD., DORSET HOUSE, TUDOR ST.. LONDON. E.C.4 www.americanradiohistory.com 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 11I I l l I1I111I I l 1111111111111111111111111111111111I111111 INDEX VOLUME XXIII JULY 4th -DECEMBER 26th, 1928 i l l l l l l __ 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I 1111111111111111 r A.B. Products -H.F. Choke, 774 Brayton Trickle Charger, The, 08e Current Topics, 11, 43, 69, 109, 133, 167, 195, Abroad, Programmes from, 15, 45, 78, 105, 135, Bright Emitters as Rectifiers, 183 231, 255, 287, 317, 359, 391, 472, 603, 531, 169, 197,- 227, 257, 283, 319, 365, 393, 468, British Acoustic Film System, The (Talking 561, 587, 633, 661, 701, 727, 765, 795, 818, 505, 533, 565, 601, 635, 673, 713, 733, 761, Films), 842 850 797, 820, 860 Phototone System (Talking Films), 792 " Cylanite," 688 Programmes from (Editorial), 1 -Broadcast ('yldon Synchratune -, Brevities, 23, 54, 85, 117, 143. 177, Twin Condensers, 743 -, Sets for, 808 203, 233, 268, 296, 323, 363, 445, 481, 515. Accumulator Carrier, Weston, 564 543, 573. 599, 641, 682, 711, 745, 772, 805. Charging, 489 832, 865 Damped but Distoitionless, - Discharge, 749 - Equalising, 272 Broadcasting Monopoly, The (Editorial), 155 Davex Eliminator, 19 Knobs, Clix, 112 Scientific Foundations of, 728 Tuners, 564 - or -, Eliminator? 750 Stations, 206 -" D.C.5," A Batteryless Receiver for -Accumulators, D.C. -

1953 the Mountaineers, Inc

fllie M®��1f�l]�r;r;m Published by Seattle, Washington..., 'December15, 1953 THE MOUNTAINEERS, INC. ITS OBJECT To explore and study the mountains, forests, and water cours es of the Northwest; to gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; to preserve by encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise, the natural beauty of North west America; to make expeditions into these regions in ful fillment of the above purposes ; to encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of out-door life. THE MOUNTAINEER LIBRARY The Club's library is one of the largest mountaineering col lections in the country. Books, periodicals, and pamphlets from many parts of the world are assembled for the interested reader. Mountaineering and skiing make up the largest part of the col lection, but travel, photography, nature study, and other allied subjects are well represented. After the period 1915 to 1926 in which The Mountaineers received books from the Bureau of Associate Mountaineering Clubs of North America, the Board of Trustees has continuously appropriated money for the main tenance and expansion of the library. The map collection is a valued source of information not only for planning trips and climbs, but for studying problems in other areas. NOTICE TO AUTHORS AND COMMUNICATORS Manuscripts offered for publication should be accurately typed on one side only of good, white, bond paper 81f2xll inches in size. Drawings or photographs that are intended for use as illustrations should be kept separate from the manuscript, not inserted in it, but should be transmitted at the same time. -

A Week's Ramble on Canada's Great Divide

The Good, the Bad, the Ugly, and the Beautiful A Week’s Ramble on Canada’s Great Divide Story and photos by Aaron Teasdale The path beneath our tires forked and, This trip would prove no exception. best!” I said to my father as we met by Finland together for fun. as always, I longed to take the path less It was our first day on the Canadian Great chance near the Goat Pond dam at the alter- It quickly became apparent the next traveled. The problem was we knew noth- Divide Route. Our group of four had pedaled nate route’s midpoint. “It’ll be great.” morning that Steve and I existed on oppo- ing about this overgrown trail that peeled out from the tourist-choked streets of Banff, But that’s the thing about rambles into site ends of the gear-packing spectrum. My off into the wilderness, except our Great Alberta that morning and I still clung to the unknown — they’re unknown. Like priority is ultralight; Steve’s is ultra-posh. Divide Mountain Bike Route map’s descrip- a goal of reaching an increasingly distant- a blind date, anything can happen. That’s I eschew panniers and trailers (too heavy), tion of it as an alternate route to Spray Lake seeming campsite that night. But, never part of the excitement. But blind dates can and consider a second pair of socks indul- Reservoir. Potentially very marshy. As some- being one to let the artifice of a schedule go horribly wrong (see: The Crying Game). gent. Steve stuffed his trailer with a camp one constitutionally incapable of sticking to interfere with a quality adventure, in the end With Dad at my side, the lovely grassy path chair, a full-sized pillow, several books, and, predetermined routes, I’m easily seduced by there was little suspense — I was powerless promptly turned into a much-less-lovely shockingly, four bags of wine. -

C. of the Late Charles I. Bushnell, Esq., Comprising His Extensive Collections

.^:^ ^-^^ .'';";if^A*' ^^^ ^^^:r i* iififc' ^•i-^*'im v<*^ 5:?^:'/; x^ 11^1 'M QJarttell Unitteraitg Hthtatg Jtljara, New gork FROM THE BENNO LOEWY LIBRARY COLLECTED BY BENNO LOEWY 1854-1919 BEQUEATHED TO CORNELL UNIVERSITY CATALOGUE OK THE LIBRARY, AUTOGRAPHS, EXGRAVINGS, &c. OF THE lATE CHARLES I. BUSH NELL, Esq. TO, BE SOLD BY Bangs & Co. Monday, April 2d, and four following days. 1883. Jln^^ ijj K.h .Jiali I Cornell University j Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924031351798 CATALOGUE OF THE LIBRARY, &e. OF THE LATE CHARLES L BUSHNELL, Esq, COMPRISING HIS EXTENSIVE COLLECTIONS OF RARE AND CURIOUS AMERICANA, OF Engravings, Autographs, Historical Relics, Wood-Blocks Engraved by Dr. Anderson, &c., &c. Compiled by ALEX'R DENHAM. TO BE SOLDAT AUCTION, Monday, April 2d, and four following days. Commencing at 3 P. M. and 7.30 P. M., each day, BY Messrs. BANGS & CO., Nos. 739 and 741 Broadway, New York. Gentlemen unable to attend the Sale, may have purchases made to their order by the Auctio?ieers. 1I^"A11 bids should be made by the Volume, and not by the set. NO T E. The late Mr. Charles I. Bushnell was widely known, not only as a persevering collector of rare and quaint books, but also as a diligent student of American history ; whose thorough knowledge of those minutiae which escape the notice of all but the painstaking specialist had been proved by his original essays and scholarly annotations to various books. -

Peace River Regional District REPORT

PEACE RIVER REGIONAL DISTRICT Emergency Executive Committee Meeting A G E N D A for the meeting to be held on Tuesday, February 7, 2017 in the Regional District offices, Dawson Creek, BC commencing at 1:00 pm Committee Chair: Director Goodings Vice-Chair: Director Rose 1. CALL TO ORDER: 2. ELECTION OF CHAIR / VICE-CHAIR: 3. NOTICE OF NEW BUSINESS: 4. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA: 5. ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES: M-1 Emergency Executive Committee Meeting Minutes of June 21, 2016 6. BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES: 7. CORRESPONDENCE: C-1 2017 Snow Survey and Water Supply Bulletin. C-2 January 25, 2017 National Energy Board – proposed changes to the Emergency Management filing requirements. 7. REPORTS: R-1 January 31, 2017 Emergency Services Budget. 8. NEW BUSINESS: 9. ITEMS FOR INFORMATION: I-1 November 6, 2016 UBCM – Emergency Program Act Review – Summary of input received from local governments. I-2 For Reference - “PRRD Emergency & Disaster Service Establishment Bylaw No. 1598, 2005” and “PRRD Emergency & Disaster Operations Bylaw No. 1599, 2005” I-3 Emergency Incident Register 10. ADJOURNMENT: PEACE RIVER REGIONAL DISTRICT EMERGENCY EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES DATE: Tuesday, June 21, 2016 PLACE: Regional District Offices, Dawson Creek, BC PRESENT: Director Karen Goodings, Electoral Area ‘B’ – Meeting Chair Director Brad Sperling, Electoral Area ‘C’ Director Leonard Hiebert, Electoral Area ‘D’ Director Dan Rose, Electoral Area ‘E’ Director Dale Bumstead, City of Dawson Creek Chris Cvik, Chief Administrative Officer Staff Trish Morgan, General Manager of Community and Electoral Area Services Jill Rickert, Community Services Coordinator Suzanne Garrett, Corporate Services Coordinator 1) Call to Order The meeting was called to order at 1:05 pm ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA: 2) Adoption of the MOVED by Director Bumstead, SECONDED by Director Hiebert, Agenda that the Emergency Executive Committee agenda for the June 21, 2016 meeting be adopted as follows: 1. -

Tonquin Valley, with the Ramparts Rising Majestically Across the Lake

in late season; in fact, very late season. I recommend down the open meadows on the west side of the pass into planning to do this route between the middle of the Tonquin show off some the best scenery in Jasper August and the middle of September (even the end of National Park, with astounding views of the Ramparts. September into early October in rare years when the Finally, the trail enters the timber and reaches Maccarib weather holds). Going then will give you the best Camp in 12 miles (19 km), before arriving at Amethyst Lakes chance of relatively dry, stable weather, and with at 13 miles (21 km). The first camp by the lake, Amethyst vacations over and kids back in school, the best Camp, is a mile farther at 14 miles (22.5 km). chance for uncrowded camps and trails. Now you are in the heart of the Tonquin Valley, with the Ramparts rising majestically across the lake. Four legal camps are situated in the Tonquin on the east side of Ame- route thyst Lakes, from Amethyst Camp to Clitheroe or Surprise Point. There is much to explore here in the Tonquin, he trailheads to the Tonquin are close to the town of depending on how many nights your permit allows you to Jasper. The start to the route described here, Maccarib camp. From Amethyst Camp, it’s less than a mile to the Trail,T begins near the Marmot ski area about 10 miles (16 lodge on the north shore of the lake, another 1.5 miles km) from Jasper: travel south 4.5 miles (7 km) on the Ice- (2.4 km) to Clitheroe Camp, and another 1 mile (1.6 km) to fields Parkway, then turn off on 93A toward the ski area.