48. Louis Armstrong West End Blues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

24Th Annual Dixieland Jazz Festival June 26, 27, 28, 29, 2014 Saint Martin’S University Macus Pavilion 5300 Pacific Ave

24th Annual Dixieland Jazz Festival June 26, 27, 28, 29, 2014 Saint Martin’s University Macus Pavilion 5300 Pacific Ave. SE • Lacey, Washington www.olyjazz.com FOUR VENUES • ONE SITE Great Bands • Large Dance Floors • Swing Set Jazz Festival Dance Lessons - Hal & Georgia Myers, California Nearby Hotels • Shuttle Service Available • Parasol Parades RV Accommodations • Tickets Available at Door INFORMATION: Charlotte Dickison - 360-943-9123 Email: [email protected] RV PARKING: Pat Herndon - 360-956-7132 Email: [email protected] www.olyjazz.com Great Bands plus special set: Tribute to Ray Smith Parmount Jazz Band buck creek evergreen classic grand dominion high sierra ivory & gold* jerry krahn & katie cavera titan hot seven* tom hook/terriers tom rigney flambeau uptown lowdown west end wolverines yerba buena stompers eddie erickson* brady mckay* Festival Times Special Events Kick-Off Party June 26 - 7pm - 10:30pm June 26 ................. 7pm - Kick off party June 26 .............................Kick off party Saint Martin’s University June 27 ..................11:00am - 10:45pm ($15.00 at the door) Marcus Pavilion June 28 .....................9:30am - 11:00pm June 27 ... Farmers Market - 11am-2pm ($15 at the door) June 29 ........................9:30am - Gospel June 29 ...........Sunday Gospel - 9:30am Bands (subject to change) HIgh Sierra • Tom Hook/Terriers Festival ....................10:45am - 3:45pm After Glow Party - 5pm - Tugboat Annies Grand Dominion Shuttle service - 1 hour before event start Food & beverages available Area Hotels (ask for Jazz Rates) Area Hotels (ask for Jazz Rates) Comfort Inn* ................................................................... $99.99 Double Tree Inn by Hilton............................................ $129.00 Lacey • 360-456-6300 Olympia • 360-570-0555 Comfort Inn Tumwater* ................................................ -

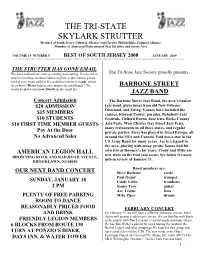

The Tri-State Skylark Strutter

THE TRI-STATE SKYLARK STRUTTER Member of South Jersey Cultural Alliance and Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance Member of American Federation of Jazz Societies and Jersey Arts VOLUME 19 NUMBER 5 BEST OF SOUTH JERSEY 2008 JANUARY 2009 ********************************************************************************************************************************* .THE STRUTTER HAS GONE EMAIL We have reduced our costs of printing and mailing. If you wish to The Tri-State Jazz Society proudly presents: help by receiving an email edition in place of this edition, please send in your email address If you did not receive it in pdf, please let us know! Please help us save money for good bands!! We BARBONE STREET would be glad to put your friends on the email list. JAZZ BAND Dd Concert Admission The Barbone Street Jazz Band, the area’s busiest $20 ADMISSION jazz band, plays tunes from old New Orleans, Dixieland, and Swing. Venues have included the $15 MEMBERS casinos, Kimmel Center, parades, Rehoboth Jazz $10 STUDENTS Festivals, Clifford Brown Jazz fests, Berks County $10 FIRST TIME MEMBER GUESTS Jazz Fests, West Chester Gay Street Jazz Fests, many restaurants in all three states, and regular Pay At the Door private parties. Steve has played in Israel Europe, all No Advanced Sales around the USA and Canada. Paul was a star in the S US Army Band for many years. Ace is a legend in the area, playing with many greats. Sonny had his AMERICAN LEGION HALL own trio at Downey’s for years. Cindy and Mike are new stars on the trad jazz scene. See below for more BROWNING ROAD AND RAILROAD AVENUE, info in review of January 11. -

CATALOGUE WELCOME to NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS and NAXOS NOSTALGIA, Twin Compendiums Presenting the Best in Vintage Popular Music

NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS/NOSTALGIA CATALOGUE WELCOME TO NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS AND NAXOS NOSTALGIA, twin compendiums presenting the best in vintage popular music. Following in the footsteps of Naxos Historical, with its wealth of classical recordings from the golden age of the gramophone, these two upbeat labels put the stars of yesteryear back into the spotlight through glorious new restorations that capture their true essence as never before. NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS documents the most vibrant period in the history of jazz, from the swinging ’20s to the innovative ’40s. Boasting a formidable roster of artists who forever changed the face of jazz, Naxos Jazz Legends focuses on the true giants of jazz, from the fathers of the early styles, to the queens of jazz vocalists and the great innovators of the 1940s and 1950s. NAXOS NOSTALGIA presents a similarly stunning line-up of all-time greats from the golden age of popular entertainment. Featuring the biggest stars of stage and screen performing some of the best- loved hits from the first half of the 20th century, this is a real treasure trove for fans to explore. RESTORING THE STARS OF THE PAST TO THEIR FORMER GLORY, by transforming old 78 rpm recordings into bright-sounding CDs, is an intricate task performed for Naxos by leading specialist producer-engineers using state-of-the-art-equipment. With vast personal collections at their disposal, as well as access to private and institutional libraries, they ensure that only the best available resources are used. The records are first cleaned using special equipment, carefully centred on a heavy-duty turntable, checked for the correct playing speed (often not 78 rpm), then played with the appropriate size of precision stylus. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

Lesson Plan Summary

Lesson Plan Summary Magic Tree House #42: A Good Night for Ghosts Scat-A-Dat-Do with Louis Armstrong FOCUS QUESTION: What contributions did Louis Armstrong make to the world of music? DURING THIS BOOK STUDY, COMMON CORE STANDARDS EACH STUDENT WILL: ADDRESSED: MUSIC AND VISUAL ARTS: Learn the definition and musical style Creative responses to texts of scat singing. Significant individuals Musical styles Practice scat singing. Write and perform an original line of READING: scat singing. Analyze texts for main idea and details. Comprehend the vocabulary of solo, duo, trio, and quartet. Summarize story parts. Read with fluency to support Study the biography of Louis comprehension. Armstrong WRITING: Record a main event and supporting Text types and purposes details of Louis Armstrong’s life. SPEAKING AND LISTENING: Present a project to the class. Comprehension and collaboration Presentation skills Respectful audience behavior 42-2S512 Created by: Melissa Summer Woodland Heights Elementary School, Spartanburg, South Carolina and Paula Cirillo, Hill Academy Moorpark, California Copyright © 2012, Mary Pope Osborne, Classroom Adventures Program, all rights reserved. Lesson Plan Magic Tree House #42: A Good Night for Ghosts Scat-a-dat-do with Louis Armstrong http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rT1Kuy922c0 DIRECTIONS: 1. INTRODUCE SCAT SINGING with Hoots the Owl at the link above. 2. DEFINE AS A CLASS: What is scat singing? 3. STUDY THE BIOGRAPHY of Louis Armstrong, who was famous for his scat singing. Students can choose to work in one of the following ensembles: SOLO (alone) DUO (with a partner) TRIO (in a group of three) QUARTET (in a group of four) Students will work in their ensembles to summarize the main ideas in a reading about Louis Armstrong’s life. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

INTRODUCTION: BLUE NOTES TOWARD a NEW JAZZ DISCOURSE I. Authority and Authenticity in Jazz Historiography Most Books and Article

INTRODUCTION: BLUE NOTES TOWARD A NEW JAZZ DISCOURSE MARK OSTEEN, LOYOLA COLLEGE I. Authority and Authenticity in Jazz Historiography Most books and articles with "jazz" in the title are not simply about music. Instead, their authors generally use jazz music to investigate or promulgate ideas about politics or race (e.g., that jazz exemplifies democratic or American values,* or that jazz epitomizes the history of twentieth-century African Americans); to illustrate a philosophy of art (either a Modernist one or a Romantic one); or to celebrate the music as an expression of broader human traits such as conversa- tion, flexibility, and hybridity (here "improvisation" is generally the touchstone). These explorations of the broader cultural meanings of jazz constitute what is being touted as the New Jazz Studies. This proliferation of the meanings of "jazz" is not a bad thing, and in any case it is probably inevitable, for jazz has been employed as an emblem of every- thing but mere music almost since its inception. As Lawrence Levine demon- strates, in its formative years jazz—with its vitality, its sexual charge, its use of new technologies of reproduction, its sheer noisiness—was for many Americans a symbol of modernity itself (433). It was scandalous, lowdown, classless, obscene, but it was also joyous, irrepressible, and unpretentious. The music was a battlefield on which the forces seeking to preserve European high culture met the upstarts of popular culture who celebrated innovation, speed, and novelty. It 'Crouch writes: "the demands on and respect for the individual in the jazz band put democracy into aesthetic action" (161). -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

S Y N C O P a T I

SYNCOPATION ENGLISH MUSIC 1530 - 1630 'gentle daintie sweet accentings1 and 'unreasonable odd Cratchets' David McGuinness Ph.D. University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts April 1994 © David McGuinness 1994 ProQuest Number: 11007892 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007892 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 10/ 0 1 0 C * p I GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ERRATA page/line 9/8 'prescriptive' for 'proscriptive' 29/29 'in mind' inserted after 'his own part' 38/17 'the first singing primer': Bathe's work was preceded by the short primers attached to some metrical psalters. 46/1 superfluous 'the' deleted 47/3,5 'he' inserted before 'had'; 'a' inserted before 'crotchet' 62/15-6 correction of number in translation of Calvisius 63/32-64/2 correction of sense of 'potestatis' and case of 'tactus' in translation of Calvisius 69/2 'signify' sp. 71/2 'hierarchy' sp. 71/41 'thesis' for 'arsis' as translation of 'depressio' 75/13ff. Calvisius' misprint noted: explanation of his alterations to original text clarified 77/18 superfluous 'themselves' deleted 80/15 'thesis' and 'arsis' reversed 81/11 'necessary' sp. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Ernest Elliott

THE RECORDINGS OF ERNEST ELLIOTT An Annotated Tentative Name - Discography ELLIOTT, ‘Sticky’ Ernest: Born Booneville, Missouri, February 1893. Worked with Hank Duncan´s Band in Detroit (1919), moved to New York, worked with Johnny Dunn (1921), etc. Various recordings in the 1920s, including two sessions with Bessie Smith. With Cliff Jackson´s Trio at the Cabin Club, Astoria, New York (1940), with Sammy Stewart´s Band at Joyce´s Manor, New York (1944), in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith´s Band (1947). Has retired from music, but continues to live in New York.” (J. Chilton, Who´s Who of Jazz) STYLISTICS Ernest Elliott seems to be a relict out of archaic jazz times. But he did not spend these early years in New Orleans or touring the South, but he became known playing in Detroit, changing over to New York in the very early 1920s. Thus, his stylistic background is completely different from all those New Orleans players, and has to be estimated in a different way. Bushell in his book “Jazz from the Beginning” says about him: “Those guys had a style of clarinet playing that´s been forgotten. Ernest Elliott had it, Jimmy O´Bryant had it, and Johnny Dodds had it.” TONE Elliott owns a strong, rather sharp, tone on the clarinet. There are instances where I feel tempted to hear Bechet-like qualities in his playing, probably mainly because of the tone. This quality might have caused Clarence Williams to use Elliott when Bechet was not available? He does not hit his notes head-on, but he approaches them with a fast upward slur or smear, and even finishes them mostly with a little downward slur/smear, making his notes to sound sour.