Table of Contents Item Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

State Building in Revolutionary Ukraine

STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM This page intentionally left blank Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM STEPHEN VELYCHENKO STATE BUILDING IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE A Comparative Study of Governments and Bureaucrats, 1917–1922 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London Unauthenticated Download Date | 3/31/17 3:49 PM © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2011 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable- based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Velychenko, Stephen State building in revolutionary Ukraine: a comparative study of governments and bureaucrats, 1917–1922/Stephen Velychenko. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4132-7 1. Ukraine – Politics and government – 1917–1945. 2. Public adminstration – Ukraine – History – 20th century. 3. Nation-building – Ukraine – History – 20th century 4. Comparative government. I. Title DK508.832.V442011 320.9477'09041 C2010-907040-2 The research for this book was made possible by University of Toronto Humanities and Social Sciences Research Grants, by the Katedra Foundation, and the John Yaremko Teaching Fellowship. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the fi nancial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities. -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

June 30, 2000

Support for Ukrainian Private Farming Sector and Scientific Collaboration: A U.S.fUkrainian Partnership Cooperative Agreement No: 121-AOO-98-00631-00 Funded by The United States Agency for International Development Mission for Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova 19 Nizhniy Val Street 254071 Kiev, Ukraine Seventh Quarter Report April 1, 2000 ~ June 30, 2000 July 2000 Submitted by International Programs Louisiana State University Agricultural Center Baton Rouge, Louisiana In association with Vinnitsa State Agriculture University International Center for Scientific Culture World Laboratory Ukraine Branch With the participation of the National Agricultural University of Ukraine INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS Office of the Director 118 Knapp Hall-louisiana State University Baton Rouge. louisiana 70803 USA Mailing address: P.O. Box 16090 Baton Rouge. louisiana 70893 USA (225) 388·6963 Fax: (225) 388·6775 Website: www.agctr.lsu.edu July 31, 2000 Dr. Oleksandr A. Muliar, Agricultural Specialist USAlD Technical Officer Office of Private Sector Development USAlD Mission 19 Nizhniy Val Street 254071 Kiev Ukraine Seventh Quarter Report for the Period April 1, 2000 to June 30, 2000. USAID Cooperative Agreement No: 121-AOO-98·00631-00 Dear Dr. Muliar: Enclosed please find the Seventh Quarter Program Report for the above Cooperative Agreement executed between USAlD and the LSU AgCenter. The report covers the program activities for the period April I, 2000 to June 30, 2000 of the project entitled, "Support for Ukrainian Private Farming Sector and Scientific Collaboration: A U.S.lUkrainian Partnership." One hard copy of this report, as required in Section 1.5.2 of the Cooperative Agreement "Monitoring and Reporting Program Performance," will be delivered to you by the World Laboratory in Kiev. -

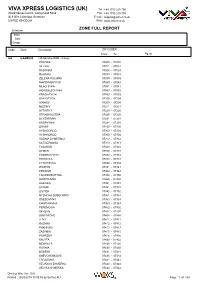

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

N in Ukraine 27 Hennadii Yefimenko

VOL 1 • ISSUE 1 • 2009 n i n o m In Memoriam: Raphael Lemkln [1900-1959] Raphael Lemkin on the Ukrainian genocide Memories of Communist and Nazi Crimes Polish Diplomats on the Holodomor Red Cross Documents on the Great Famine HOLODOMOR STUDIES EDITOR Roman Serbyn Universite du Quebec a Montreal, Canada Email: Serbvn.Roman@Videotron. ca HOLODOMOR STUDIES is published semi annually. Subscription rates are: Institutions - $40.00; Individuals - $20.00. USA postage is $6.00; Canadian postage is $12.00; foreign postage is $20.00. Send payment to: Charles Schlacks, Publisher, P.O. Box 1256, Idyllwild, CA 92549-1256, USA. Email: [email protected] Cover Design: Olena Sullivan, Toronto, Can ada. www.olena.ca Manuscripts submitted for possible publication should be sent to the editor. Manuscripts ac cepted for publication should be sent to the pub lisher as email attachments or on CDs suitable for Windows XP and Word 2003. Copyright © 2009 by Charles Schlacks, Pub lisher All rights reserved Printed in the USA Vol. 1, No. 1 Winter-Spring 2009 HOLODOMOR STUDIES TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLISHER’S PREFACE v Charles Schlacks EDITOR’S FOREWORD vii Roman Serbyn IN MEMORIAN: RAPHAEL LEMKIN [1900-1959] Lemkin on the Ukrainian Genocide 1 Roman Serbyn Soviet Genocide in Ukraine 3 Raphael Lemkin ARTICLES Competing Memories o f Communist and Nazis Crimes in Ukraine 9 Roman Serbyn The Soviet Nationalities Policy Change of 1933, or Why “Ukrainian Nationalism ” Became the Main Threat to Stalin in Ukraine 27 Hennadii Yefimenko Foreign Diplomats on the -

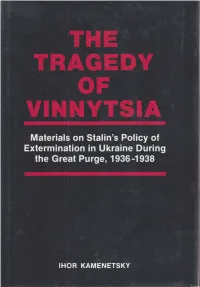

The Vinnytsia Mass Graves and Some Other Soviet Sites of Execution

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by L.R. Wynar...................................................... vii Acknowledgements ......................................................... xii Editorial Policy ............................................................... xv I. INTRODUCTION by lhor Kamenetsky Humanitarian and Anti-Humanitarian Trends in Modern History ............................................................1 The Vinnytsia Case and the Yezhovshchyna Era.. ................ .15 The Role of the Local Ukrainian Population and of the German Occupation Forces in the Vinnytsia Case .....................................................22 The Vinnytsia Mass Graves and Some Other Soviet Sites of Execution ........................ 31 Conclusion.. ................................................................... .35 11. TESTIMONIES AND HEARINGS M. Seleshko, Vinnystsia - The Katyn of Ukraine (A Report by an Eyewitness) ............................41 Petro Pavloyvch, I Saw Hell: Fragment of Reminiscences........................................................... .52 Bishop Sylvester, The Vynnytsya Tragedy.. ........................ .54 Archbishop Hyhoriy, P. Pavlovych, K. Sybirsky, Testimony on the Crime in Vynnytsya ............................................................ .56 lhor Kamenetsky, Interview with an Eyewitness in August 1987 .......................................... .60 Archbishop Hyhoriy, Funeral Eulogy Delivered at Vinnytsia, October 3, 1943.. ....................... .63 Congressional Hearings, The Crimes of Khrushchev, Part -

Admin 2 Number of Partners with Ongoing

UKRAINE, Multipurpose Cash - Admin 2 Number of Partners with ongoing/completed Projects ( as of 2Sem8en iDvkaecembeSerre d2yna0-B1uda6) Novhorod-Siverskyi Yampil BELARUS Horodnia Ripky Shostka Liubeshiv Zarichne Ratne Snovsk Koriukivka Hlukhiv Kamin-Kashyrskyi Dubrovytsia Korop Shatsk Stara Chernihiv Sosnytsia Krolevets Volodymyrets Vyzhivka Kulykivka Mena Ovruch Putyvl Manevychi Sarny Rokytne Borzna Liuboml Kovel Narodychi Olevsk Konotop Buryn Bilopillia Turiisk Luhyny Krasiatychi Nizhyn Berezne Bakhmach Ivankiv Nosivka Rozhyshche Kostopil Yemilchyne Kozelets Sumy Volodymyr-Volynskyi Korosten Ichnia Talalaivka Nedryhailiv Lokachi Kivertsi Malyn Bobrovytsia Krasnopillia Romny RUSSIAN Ivanychi Lypova Lutsk Rivne Korets Novohrad-Volynskyi Borodianka Vyshhorod Pryluky Lebedyn FEDERATION Zdolbuniv Sribne Dolyna Sokal Mlyniv Radomyshl Brovary Zghurivka Demydivka Hoshcha Pulyny Cherniakhiv Makariv Trostianets Horokhiv Varva Dubno Ostroh Kyiv Baryshivka Lokhvytsia Radekhiv Baranivka Zhytomyr Brusyliv Okhtyrka Velyka Pysarivka Zolochiv Vovchansk Slavuta Boryspil Yahotyn Pyriatyn Chornukhy Hadiach Shepetivka Romaniv Korostyshiv Vasylkiv Bohodukhiv Velykyi Kamianka-buzka Radyvyliv Iziaslav Kremenets Fastiv Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi Hrebinka Zinkiv Krasnokutsk Burluk Bilohiria Polonne Chudniv Andrushivka Derhachi Zhovkva Busk Brody Shumsk Popilnia Obukhiv Myrhorod Kharkiv Liubar Berdychiv Bila Drabiv Kotelva Lviv Lanivtsi Kaharlyk Kolomak Valky Chuhuiv Dvorichna Troitske Zolochiv Tserkva Orzhytsia Khorol Dykanka Pechenihy Teofipol Starokostiantyniv -

The Holocaust in Ukraine: New Sources and Perspectives

THE CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum promotes the growth of the field of Holocaust studies, including the dissemination of scholarly output in the field. It also strives to facilitate the training of future generations of scholars specializing in the Holocaust. Under the guidance of the Academic Committee of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, the Center provides a fertile atmosphere for scholarly discourse and debate through research and publication projects, conferences, fellowship and visiting scholar opportunities, and a network of cooperative programs with universities and other institutions in the United States and abroad. In furtherance of this program the Center has established a series of working and occasional papers prepared by scholars in history, political science, philosophy, religion, sociology, literature, psychology, and other disciplines. Selected from Center-sponsored lectures and conferences, THE HOLOCAUST or the result of other activities related to the Center’s mission, these publications are designed to make this research available in a timely IN UKRAINE fashion to other researchers and to the general public. New Sources and Perspectives Conference Presentations 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW Washington, DC 20024-2126 ushmm.org The Holocaust in Ukraine: New Sources and Perspectives Conference Presentations CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2013 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The articles in this collection are not transcripts of the papers as presented, but rather extended or revised versions that incorporate additional information and citations. -

Right-Bank Ukraine History in Statistics

Right-Bank Ukraine in the middle of the 19-th century. History in statistics Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Vinnytsia National Agrarian University Yu. Boiko Right-Bank Ukraine in the middle of the 19-th century. History in statistics VNAU 2020 UDK 94(477.4)"19" B -77 Recommended by the Academic Council of Vinnytsia National Agrarian University (Protocol No. 5 of nov. 29 2019) Reviewers Legun Yurii – Doctor of History, professor, director of the State Archives of Vinnytsia Region; Melnychuk Oleh – Doctor of History, professor, head of the Department of World History Faculty of History, Ethnology and Law VSPU named after Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi; Stepanchuk Yurii – Doctor of History, professor of the Department of History and Culture of Ukraine Faculty of History, Ethnology and Law VSPU named after Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi. Boiko Yurii. B-77 Right-Bank Ukraine in the middle of the 19-th century. History in statistics / Yurii Boiko; Vinnytsia National Agrarian University. - Vinnytsia: VNAU, 2020. 229 p. The monograph is devoted to the coverage of issues of the administrative structure, management system, demography, ethno- confessional and social situation, economy of Right-Bank Ukraine in the middle of the 19-th century on the basis of various authentic statistical sources, using modern methods of paleosociological and paleoeconomic modelling. The publication is intended for teachers, students, anyone interested in the history of Ukraine. ISBN 978-617-7789-06-1 UDK 94(477.4)"19" B-77 ® Boiko Yurii, 2020 ISBN 978-617-7789-06-1 ® VNAU, 2020 Content Content Preface 9 1. Administrative structure and management 10 1.1. -

Dedication of Memorial Sites for Murdered Jews in Ukraine

«Protecting Memory» Dedication of Memorial Sites for Murdered Jews in Ukraine Berdychiv, Chashin, Baraschi, Samhorodok, Chukiv, Lypovets’, Vakhnivka, Plyskiv 16 –19 September 2019 www.erinnerungbewahren.de Ljubar, June 2019: The remembrance of annihilated Jewish communities returns to the villages and towns in Ukraine. Maia Bondarchuk, the last living Jew in Ljubar, holds a photo of her murdered grandparents during the ceremonial dedication of the memorial. © Stiftung Denkmal, Foto: Anna Voitenko Project «Protecting Memory»: Dedication of nine Holocaust memorial sites and opening of an open-air exhibition in Ukraine on September 16–19, 2019 After the dedication of six memorial sites in June 2019, «Protecting Memory» will hand over to the public nine Jewish memorial sites along with an open-air exhibition in Berdytschiw between 16-19 September 2019. These memorial sites are located in regions Zhitomir and Vinnitsia (Plyskiv (two sites), Vakhnivka (two sites), Samhorodok, Chukiv, Lypovets’, Chashin and Baraschi). Family members of Holocaust survivors will attend the ceremonies along with representatives from the Embassy of Israel, the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine, the German Embassy in Kyiv, the German Foreign Office, members of the Ukrainian administration, local citizens, as well as representatives from Jewish organizations and project partners. In connection with the ceremonial activities, it will be possible to discuss the current status of commemorative politics and the politics of history with participants from different states and international organizations. The international project «Protecting Memory» from the Foundation Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, carried out in close cooperation with the Ukrainian Centre for Holocaust Studies in Kiev, has dedicated itself to transforming mass shooting sites of Jews and Roma in Ukraine into dignified memorial and information sites.