Minority Commercial Radio Broadcasters Sandoval MMTC 2009 Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FCC Encyclopedia / Why AM Radio Stations Must Reduce Power, Change Operations, Or Cease

Why AM Radio Stations Must Reduce Power, Change Operations, or Cease Broadcasting at Night | FCC.gov Federal Communications Commission The FCC Our Work Tools & Data Business & Licensing Bureaus & Offices Search Take Action Comment, Complain, Discuss Transition FCC.gov Home / The FCC / FCC Encyclopedia / Why AM Radio Stations Must Reduce Power, Change Operations, or Cease... FCC Encyclopedia Print Email FCC Highlights Why AM Radio Stations Must Reduce Power, Change Operations, or Cease Broadcasting at Night FY 2013 Regulatory Fees Most AM radio stations are required by the FCC's rules to reduce their power or cease operating at night in order to avoid interference to other AM stations. FCC rules governing the daytime and nighttime operation of AM radio stations are a consequence of the laws of physics. Because of the way in which the relatively long wavelengths (see FY 2013 Regulatory Fees are due by Footnote 1) of AM radio signals interact with the ionized layers of the ionosphere miles 11:59 p.m. Eastern Time, Sept. 20 above the earth's surface, the propagation of AM radio waves changes drastically from 2013. daytime to nighttime. This change in AM radio propagation occurs at sunset due to 20, 2013 radical shifts in the ionospheric layers, which persist throughout the night. During on September daytime hours when ionospheric reflection does not occur to any great degree,archived AM signals 11-17483 Quick Links travel principally by conduction over the surface of the earth.No. This is known as Inc. "groundwave" propagation. Useful daytime AM service is generally limited to a radius of v. -

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

1044 RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager CHAPTE ADA WJNZ 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sales RX• ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. GENERAL INFORMATION / STATISTICS of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. (616) 343-3200 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 669, 5310 N. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 82, No. 17 ● June 22, 2015 ● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 1 … Club Convention 16 … International DX Digest 25 … Geomagnetic Indices 3 … AM Switch 21 … Confirmed DXer 26 … GYDXA 1230 kHz 8 … Domestic DX Digest West 22 … DX Toolbox 31 … GYDXA Updates 12 … Domestic DX Digest East From the Publisher: This is our last issue before the All‐Club DX Convention in Fort Membership Report Wayne July 10‐12. If you haven’t made plans to join us yet, all the information you need starts at “Here are my next year’s dues in the NRC. I the bottom of this page. Hope to see many of you am hoping to be at the convention in Fort Wayne in Fort Wayne! in July, as it will be a great dividing line between Note that new station CJLI‐700 Calgary is now my first fifty years in both NRC and IRCA and on the air 24/7 testing. Station will be REL with my second fifty years in the two clubs.” – Rick slogan “The Light.” Most power goes north, but Evans perhaps we’ll see some loggings of this new New Members – Welcome to Charles Smith, target here in DX News soon. Salem, OR; Michael Vitale, Pinckney, MI; and NRC AM Log Sold Out: The 35th Edition of Gary Whittaker, Albany, NY. Glad to have you the NRC AM Log is now sold out. Wayne has with us! begun working on the 36th Edition and we’ll be Returning Member – And welcome back to updating you on how you can help make the James McGloin, Lockport, IL. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and Order

Federal Communications Commission FCC 08-126 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Assessment and Collection of Regulatory Fees for ) MD Docket No. 08-65 Fiscal Year 2008 ) RM No.-11312 ) Amendment of Parts 1, 21, 73, 74, and 101 of the ) Commission’s Rules to Facilitate the Provision of ) WT Docket No. 03-66 Fixed and Mobile Broadband Access, Educational ) and Other Advanced Services in the 2150-2162 ) and 2500-2690 MHz Bands ) NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING AND ORDER Adopted: May 7, 2008 Released: May 8, 2008 Comment Date: May 30, 2008 Reply Comment Date: June 6, 2008 By the Commission: TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 II. DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................................ 2 A. FY 2008 Regulatory Fee Assessment Methodology -- Development of FY 2008 Regulatory Fees ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. Calculation of Revenue and Fee Requirements......................................................................... 4 2. Additional Adjustments to Payment Units................................................................................ 5 a. Commercial Mobile Radio Service (“CMRS”) Messaging Service ................................... 5 b. Regulatory -

Hamady Middle/High School Westwood Heights Schools

Hamady Middle/High School Westwood Heights Schools 3223 W. Carpenter Rd. • Flint, MI 48504 Office: (810) 591-0890 • Fax: (810) 591-5140 PARENT HANDBOOK & STUDENT CODE OF CONDUCT GRADES 7-12 2017-2018 1 Hamady Middle/High School Parent Handbook/Student Code of Conduct Student and Parent Acknowledgement & Pledge The Parent Handbook/Student Code of Conduct 2017-2018 has been developed to help your child receive quality instruction in an orderly educational environment. The school district needs your cooperation in this effort. Please review and discuss the Parent Handbook/Student Code of Conduct 2017-2018 with your child, sign this sheet and return it with your child to school. Should you have any questions when reviewing the Parent Handbook/Student Code of Conduct 2017-2018, please contact your school administration. I have reviewed the Parent Handbook/Student Code of Conduct 2017-2018 with my child, and we understand the rights and responsibilities therein. Parent/Guardian: __________________________________________________________________ (Print clearly) __________________________________________________________________ (Sign your name) Date: _________________ To help keep my school safe, I pledge to show good Hawk Character, work to the best of my ability and adhere to the guidelines within the Parent Handbook/Student Code of Conduct 2017-2018. Student Name: ____________________________________________________________________ (Print clearly) Student Signature: _________________________________________________________________ (Sign your name) Grade: ________ Date: _________________ FAILURE TO RETURN THIS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT WILL NOT RELIEVE A STUDENT OR THE PARENT/GUARDIAN FROM BEING RESPONSIBLE FOR KNOWING OR COMPLYING WITH THE RULES CONTAINED WITHIN THE PARENT HANDBOOK/STUDENT CODE OF CONDUCT 2017-2018. 2 Westwood Heights Schools Administrative Office 3400 N. Jennings Rd. Flint, MI 48504 (810) 591-0870 Mr. -

FINAL REPORT FIRST MEETING of PERMANENT CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE II: RADIOBROADCASTING (PCC.II) August 22 - 26, 1994 Ottawa, Canada

OEA/Ser.L/XVII.4.1 PCC.II-32/94 rev.1 December 2, 1994 FINAL REPORT FIRST MEETING OF PERMANENT CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE II: RADIOBROADCASTING (PCC.II) August 22 - 26, 1994 Ottawa, Canada 2 A. MINUTES OF THE WORKING SESSION 1. FIRST WORKING SESSION Date: August 22, 1994 Time: 11:00 a.m. Chairman: Mr. G. Ronald Begley (Canada) Vice-chairman: Mr. Osvaldo Martin Beunza (Argentina) The Chairman opened the meeting with some brief introductory remarks. The draft agenda (PCC.II-02/94) was then considered and adopted with some minor adjustments. The Chairman indicated a strong desire to have a serious discussion sometime later in the week regarding the future of PCC.II. Larry Olson (USA) was appointed chairman of the drafting group to prepare the report of the meeting. Finally, to allow more time to consider future work of the group, the order of business was adjusted so that the DAB/HDTV seminar was moved to the beginning of the week with the PCC.II meeting to begin after the conclusion of the seminar. SEMINAR - DIGITAL AUDIO RADIO BROADCASTING (DAB) The following are brief summaries of the documents presented during the seminar on Digital Audio Broadcasting: SEMDB-06/94 Field Tests of Digital Audio Broadcasting Using the NASA Tracking and Data Relay Satellite at S-Band. (USA) A series of satellite-based experiments were completed at the end of July 1994 on mobile reception of compact disk quality audio. These experiments were conducted using Digital System B (Voice of America/ Jet Propulsion Laboratory) at S-Band (2.05 GHz) using one of NASA's Tracking and Data Relay Satellites while it was moved from an equatorial location over Brazil to one over Hawaii. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DXers since 1933 Volume 84, No. 15 ● May 8, 2017 ●(ISSN 0737‐1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 10 … Domestic DX Digest East 14 … International DX Digest 7 … Domestic DX Digest West 13 … Pro Sports Networks 18 … DX Toolbox 9 … Confirmed DXer Log Sold Out: The 37th Edition of the NRC AM Miller was getting ready to deliver a Rolls Royce Log is sold out. Now we turn to making the 38th to NY! Michigan DXer Frank Merrill, Jr logged Edition better than ever for this fall! CHUB‐1570 BC & KASH‐1600 OR at their 3 AM Joint Convention 2017: The joint IRCA‐NRC‐ s/offs. DecaloMania convention is August 17‐20 in Reno, 25 Years Ago – From the May 11, 1992 issue of Nevada. The location will be the Best Western DX News: Two news articles in the 48‐page Airport Plaza Hotel, 1981 Terminal Way, Reno bulletin: “Is AM Dying” by our Dominican NV 89502. For reservations, call (775) 348‐6371 Republic DXer Cesar Objio & “A New Tune for and request the International Radio Club of Radio‐Hard Times” by one Edmund L. Andrews. America room rate of $100/night (plus tax). Dale Park (HI) heard WXLG. Who? Station in the Registration fee (not including the banquet) is Marshall Islands on 1224 via his Sangean ATS‐ $25 payable to Mike Sanburn, P.O. Box 1256, 803A. 1490 Graveyard Stats posted – furthest Bellflower, CA 90707‐1256, or by PayPal (add $1 Laurie Boyer (New Zealand) logs of WOLF‐NY @ fee) to [email protected]. Include 9,348 miles and KAIR‐AZ @ 7,386 miles. -

Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) ) ) )

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC In the matter of: ) ) Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) MB Docket 13-249 ) ) COMMENTS OF REC NETWORKS One of the primary goals of REC Networks (“REC”)1 is to assure a citizen’s access to the airwaves. Over the years, we have supported various aspects of non-commercial micro- broadcast efforts including Low Power FM (LPFM), proposals for a Low Power AM radio service as well as other creative concepts to use spectrum for one way communications. REC feels that as many organizations as possible should be able to enjoy spreading their message to their local community. It is our desire to see a diverse selection of voices on the dial spanning race, culture, language, sexual orientation and gender identity. This includes a mix of faith-based and secular voices. While REC lacks the technical knowledge to form an opinion on various aspects of AM broadcast engineering such as the “ratchet rule”, daytime and nighttime coverage standards and antenna efficiency, we will comment on various issues which are in the realm of citizen’s access to the airwaves and in the interests of listeners to AM broadcast band stations. REC supports a limited offering of translators to certain AM stations REC feels that there is a segment of “stand-alone” AM broadcast owners. These owners normally fall under the category of minority, women or GLBT/T2. These owners are likely to own a single AM station or a small group of AM stations and are most likely to only own stations with inferior nighttime service, such as Class-D stations. -

Broadcast Actions 9/23/2004

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 45826 Broadcast Actions 9/23/2004 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/13/2004 DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR LICENSE TO COVER GRANTED ND BLEDT-20031104ABX KSRE-DT PRAIRIE PUBLIC License to cover construction permit no: BMPEDT-20030616AAE, 53313 BROADCASTING, INC. callsign KSRE. E CHAN-40 ND , MINOT Actions of: 09/20/2004 FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR MAJOR MODIFICATION TO A LICENSED FACILITY DISMISSED NC BMJPFT-20030312AJR DW282AJ TRIAD FAMILY NETWORK, INC. Major change in licensed facilities 87018 E NC , BURLINGTON Dismissed per applicant's request-no letter was sent. 104.5 MHZ TELEVISION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE DISMISSED MT BALCT-20040305ACI KTGF 13792 MMM LICENSE LLC Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended From: MMM LICENSE LLC E CHAN-16 MT , GREAT FALLS To: THE KTGF TRUST, PAUL T. LUCCI, TRUSTEE Form 314 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED OH BR-20040329AIT WJYM 31170 FAMILY WORSHIP CENTER Renewal of License CHURCH, INC. E 730 KHZ OH , BOWLING GREEN Page 1 of 158 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 45826 Broadcast Actions 9/23/2004 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 09/20/2004 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED MI BR-20040503ABD WLJW 73169 GOOD NEWS MEDIA, INC. -

Review of Spectrum Management Practices Richard M

Federal Communications Commission International Bureau Strategic Analysis and Negotiations Division Review of Spectrum Management Practices Richard M. Nunno Regional and Industry Analysis Branch August 30, 2002 Table of Contents page I. Introduction 1 II. Background 1 III. Regulatory Structures for Spectrum Management 2 IV. Spectrum Allocation and Service Rules 5 V. Spectrum Assignment 8 VI. Compliance and Enforcement 11 VII. Cross-Cutting Spectrum Management Issues 11 Introduction This report supplements the information provided in the FCC’s Connecting the Globe: A Regulator’s Guide to Building a Global Community,1 which has been widely disseminated as a reference in organizing a regulatory framework for telecommunications. This new report updates and expands upon Connecting the Globe, giving telecommunications regulators additional material and references to use in establishing a regulatory authority for spectrum management. While a long list of actions is necessary in establishing spectrum policies for the myriad of wireless services, it is hoped that this Guide will help regulators to think through the critical issues they will encounter, and provide references for further study of specific issues. Background The radiofrequency spectrum, a limited and valuable resource, is used for all forms of wireless communications, including radio and television broadcast, cellular telephony, telephone radio relay, aeronautical and marine navigation, and satellite command, control, and communications. The radiofrequency spectrum (or simply, the “spectrum”) is used to support a wide variety of applications in commerce, government, and interpersonal communications. The growth of telecommunications and information services has led to an ever-increasing demand for spectrum among competing businesses, government agencies, and other groups. -

Monitoring Times 2000 INDEX

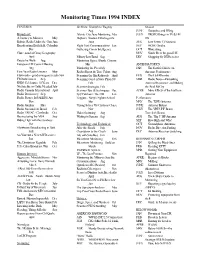

Monitoring Times 1994 INDEX FEATURES: Air Show: Triumph to Tragedy Season Aug JUNE Duopolies and DXing Broadcast: Atlantic City Aero Monitoring May JULY TROPO Brings in TV & FM A Journey to Morocco May Dayton's Aviation Extravaganza DX Bolivia: Radio Under the Gun June June AUG Low Power TV Stations Broadcasting Battlefield, Colombia Flight Test Communications Jan SEP WOW, Omaha Dec Gathering Comm Intelligence OCT Winterizing Chile: Land of Crazy Geography June NOV Notch filters for good DX April Military Low Band Sep DEC Shopping for DX Receiver Deutsche Welle Aug Monitoring Space Shuttle Comms European DX Council Meeting Mar ANTENNA TOPICS Aug Monitoring the Prez July JAN The Earth’s Effects on First Year Radio Listener May Radio Shows its True Colors Aug Antenna Performance Flavoradio - good emergency radio Nov Scanning the Big Railroads April FEB The Half-Rhombic FM SubCarriers Sep Scanning Garden State Pkwy,NJ MAR Radio Noise—Debunking KNLS Celebrates 10 Years Dec Feb AntennaResonance and Making No Satellite or Cable Needed July Scanner Strategies Feb the Real McCoy Radio Canada International April Scanner Tips & Techniques Dec APRIL More Effects of the Earth on Radio Democracy Sep Spy Catchers: The FBI Jan Antenna Radio France Int'l/ALLISS Ant Topgun - Navy's Fighter School Performance Nov Mar MAY The T2FD Antenna Radio Gambia May Tuning In to a US Customs Chase JUNE Antenna Baluns Radio Nacional do Brasil Feb Nov JULY The VHF/UHF Beam Radio UNTAC - Cambodia Oct Video Scanning Aug Traveler's Beam Restructuring the VOA Sep Waiting