Conceptualising a Visual Culture Curriculum for Greek Art Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cat Stevens Debuta En Chile Con Dos Conciertos El Cantautor Británico Yusuf Islam Llega Por Primera Vez a Santiago Para Presentarse En Noviembre

DOMINGO 23 DE JUNIO DE 2013 ESPECTÁCULOS [email protected] C19 KC & The Sunshine Band regresa a Chile La banda realizará cuatro conciertos en el país entre el 5 y el 8 de diciembre en los casinos Enjoy Johansson reemplaza de Antofagasta, Coquimbo, Santiago y Viña del a Samantha Morton Mar. Las entradas van desde los $57 mil. Schwarzenegger en “Her” encabeza filme de zombies La actriz norteamericana Scarlett Johansson El actor austriaco protagonizará la cinta “Maggie”, tomó el rol de Samantha Morton en la nueva de Henry Hobson. Se trata de una producción cinta de Spike Jonze “Her”. Pese a que la pro- postapocalíptica, donde interpretará a un padre “Transformers 4” ducción estaba casi terminada y Morton había que debe proteger a su hija que se convierte en filmado sus escenas, el director señaló que “el zombie. no destruirá Beijing personaje no encajaba y necesitaba a alguien Tras los rumores que circularon en redes diferente”, por lo tanto, asignó el rol a la pro- Helena Bonham Carter, sociales, que indicaban una destrucción de tagonista de “Match point”. “Her” es una de hada madrina diversos íconos de la capital China en la película de ciencia ficción que cuenta, además, cuarta entrega de “Transformers”, los pro- con Joaquin Phoenix, Rooney Mara y Amy La nueva versión de “Cenicienta”, dirigida por ductores de la cinta debieron aclarar que el Adams en el reparto. Kenneth Branagh, confirmó a Helena Bonham rodaje en Beijing no incluye escenas que Carter en el rol de hada madrina. La cinta comienza dañen el patrimonio de la ciudad. -

International Sales Autumn 2017 Tv Shows

INTERNATIONAL SALES AUTUMN 2017 TV SHOWS DOCS FEATURE FILMS THINK GLOBAL, LIVE ITALIAN KIDS&TEEN David Bogi Head of International Distribution Alessandra Sottile Margherita Zocaro Cristina Cavaliere Lucetta Lanfranchi Federica Pazzano FORMATS Marketing and Business Development [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mob. +39 3351332189 Mob. +39 3357557907 Mob. +39 3334481036 Mob. +39 3386910519 Mob. +39 3356049456 INDEX INDEX ... And It’s Snowing Outside! 108 As My Father 178 Of Marina Abramovic 157 100 Metres From Paradise 114 As White As Milk, As Red As Blood 94 Border 86 Adriano Olivetti And The Letter 22 46 Assault (The) 66 Borsellino, The 57 Days 68 A Case of Conscience 25 At War for Love 75 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 112 A Good Season 23 Away From Me 111 Boundary (The) 50 Alex&Co 195 Back Home 12 Boyfriend For My Wife (A) 107 Alive Or Preferably Dead 129 Balancing Act (The) 95 Bright Flight 101 All The Girls Want Him 86 Balia 126 Broken Years: The Chief Inspector (The) 47 All The Music Of The Heart 31 Bandit’s Master (The) 53 Broken Years: The Engineer (The) 48 Allonsanfan 134 Bar Sport 118 Broken Years: The Magistrate (The) 48 American Girl 42 Bastards Of Pizzofalcone (The) 15 Bruno And Gina 168 Andrea Camilleri: The Wild Maestro 157 Bawdy Houses 175 Bulletproof Heart (A) 1, 2 18 Angel of Sarajevo (The) 44 Beachcombers 30 Bullying Lesson 176 Anija 173 Beauty And The Beast (The) 54 Call For A Clue 187 Anna 82 Big Racket (The) -

As Transformações Nos Contos De Fadas No Século Xx

DE REINOS MUITO, MUITO DISTANTES PARA AS TELAS DO CINEMA: AS TRANSFORMAÇÕES NOS CONTOS DE FADAS NO SÉCULO XX ● FROM A LAND FAR, FAR AWAY TO THE BIG SCREEN: THE CHANGES IN FAIRY TALES IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Paulo Ailton Ferreira da Rosa Junior Instituto Federal Sul-rio-grandense, Brasil RESUMO | INDEXAÇÃO | TEXTO | REFERÊNCIAS | CITAR ESTE ARTIGO | O AUTOR RECEBIDO EM 24/05/2016 ● APROVADO EM 28/09/2016 Abstract This work it is, fundamentally, a comparison between works of literature with their adaptations to Cinema. Besides this, it is a critical and analytical study of the changes in three literary fairy tales when translated to Walt Disney's films. The analysis corpus, therefore, consists of the recorded texts of Perrault, Grimm and Andersen in their bibliographies and animated films "Cinderella" (1950), "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" (1937) and "The little Mermaid "(1989) that they were respectively inspired. The purpose of this analysis is to identify what changes happened in these adapted stories from literature to film and discuss about them. Resumo Este trabalho trata-se, fundamentalmente, de uma comparação entre obras da Literatura com suas respectivas adaptações para o Cinema. Para além disto, é um estudo crítico e analítico das transformações em três contos de fadas literários quando transpostos para narrativas fílmicas de Walt Disney. O corpus de análise, para tanto, é composto pelos textos registrados de Perrault, Grimm e Andersen em suas respectivas bibliografias e os filmes de animação “Cinderella” (1950), “Branca de Neve e os Sete Anões” (1937) e “A Pequena Sereia” (1989) que eles respectivamente inspiraram. -

Erreway Cuatro Caminos De Que Muere

Erreway cuatro caminos de que muere Continue 100Join Yahoo Respuestas y obtener 100 puntos hoy. Términos Privacidad AdChoicesRSSAyudaAbout RespuestasGuía comunitaria Socios para el conocimiento de liderazgo Puntos NivelesEnvío de comentarios Erreway: 4 CaminosDirectorEzequiel CrupffProducido Natalia La Portatomes YankelevichPis Co KeoleyanLily Ann MartinNarrated byCarla PandolfiMusic de Silvio FurmaskiDiego GrimblatCris MorenaCinematographyMiguel AbalEd porSusar Custodio Distributedbuena Vista International, Chris Morena Group, Yair Dory International, RGBRelease Fecha 1 de julio, 2004 (2004-07-01) Duración 102 minutosCountryArgentinaLanguageSpanish Erreway: 4 caminos (Erreway: 4 Ways) es una película argentina de 2004, una secuela de la telenovela argentina Rebel Way. La trama de la película se reanuda unos meses más tarde, con el final de la serie de televisión; después de que los chicos de la manera rebelde se graduaron de la escuela secundaria, decidieron hacer un viaje para tratar de convertirse en estrellas del pop. Erreway: 4 caminos, y habla de las formas que los chicos tomarán al final de los mejores momentos de sus vidas, los de la adolescencia. El grupo tendrá que pasar por momentos hermosos, como descubrir el hecho de que Mia está embarazada del hijo de Manuel, que se convertirá en una niña a la que llamarán: Candela. Pero también tendrán que pasar por momentos muy difíciles, como descubrir la enfermedad de Mia, que no tiene cura. Sin embargo, Rebelde Way se hará famosa y vivirá de nuevo a través de Candela, quien, como mujer -

THE EXHIBITION ROAD OPENING Boris Johnson Marks the Offi Cial Unveiling Ceremony: Pages 5 and 6

“Keep the Cat Free” ISSUE 1509 FELIX 03.02.12 The student voice of Imperial College London since 1949 THE EXHIBITION ROAD OPENING Boris Johnson marks the offi cial unveiling ceremony: Pages 5 and 6 Fewer COMMENT students ACADEMIC ANGER apply to university OVERJOURNALS Imperial suffers 0.1% THOUSANDS TO REFUSE WORK RELATED TO PUBLISHER Controversial decrease from 2011 OVER PROFIT-MAKING TACTICS material on drugs Alexander Karapetian to 2012 Page 12 Alex Nowbar PAGE 3 There has been a fall in university appli- cations for 2012 entry, Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) ARTS statistics have revealed. Referred to as a “headline drop of 7.4% in applicants” by UCAS Chief Executive Mary Curnock Cook, the newly published data includes all applications that met the 15 January equal-consideration deadline. Imperial College received 14,375 applications for 2012 entry, down from 14,397 for 2011, a 0.1% decrease. Increased fees appear to have taken a toll. Towards the end of 2011 preliminary fi gures had indicated a 12.9% drop in To Bee or not to Bee university applications in comparison to the same time last year. Less marked but in Soho still signifi cant, 7.4% fewer applications were received for this cycle. Consider- Page 18 ing applications from England UCAS describes the true fi gures: “In England application rates for 18 year olds have decreased by around one percentage point in 2012 compared to a trend of in- creases of around one per cent annually HANGMAN ...Continued on Page 3 TEDx COMES TO IMPERIAL: Hangman gets a renovation PAGE 4 Page 39 2 Friday 03 february 2012 FELIX HIGHLIGHTS What’s on PICK OF THE WEEK CLASSIFIEDS This week at ICU Cinema Fashion for men. -

IMAGES from the POETRY from 9 Apr 2012 to 24 Nov 2012 10:00-18:00

ILLUSTRATING KEATS: IMAGES FROM THE POETRY From 9 Apr 2012 to 24 Nov 2012 10:00-18:00 "ILLUSTRATING KEATS: Images from the Poetry" The Keats-Shelley House's current exhibition presents a selection of images from major illustrated editions of Keats's poems from 1856 to the present day, telling the story of the interpretation of Keats in a fresh and fascinating way. Price: Entrance to the exhibition is included in the museum's normal entrance fee. Location: Salone. "THE BRONTËS AND THE SHELLEYS - CRAFTING STORIES FROM LIVES": A TALK BY JULIET GAEL ON SATURDAY 10 NOVEMBER AT 16.00 10 Nov 2012 from 16:00 to 18:00 Janice Graham, writing as Juliet Gael, is the author of the critically acclaimed historical novel Romancing Miss Brontë, and is currently working on a follow-up novel that deals with the fascinating lives of the Shelleys. Part literary reading, part discussion, and part work-in-progress seminar, Juliet will address the creative problems involved in romanticising the lives of authors, and will give us some tantalising sneak previews into the process of writing her book about the Shelleys. Everyone is welcome and the museum's normal standard entrance fee applies. Please call on 06 678 4235 or email info@keats to reserve a place. Otherwise just come along on Saturday the 10th of November, and enjoy some refreshments after! To know more about Romancing Miss Brontë please click on the following link:http://www.romancingmissbronte.com/book.html Price: The price is included in the normal entrance fee. Location: Salone. -

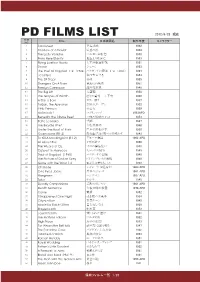

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

Drew Edward Johnson 1835 N Screenland Drive, Burbank, CA

Drew Edward Johnson 1835 N Screenland Drive, Burbank, CA. 91505 (818) 445-1006 [email protected] http://drewedwardjohnson.deviantart.com www.facebook.com/The-Art-of-Drew-Edward-Johnson Biography Drew Edward Johnson began his illustration career in 1996 as series artist on Dark Horse Comics’/Lucasfilm’s STAR WARS: X-WING ROGUE SQUADRON comic book. His work has since been published by DC Comics, Marvel Comics, Image Comics, Wildstorm Productions, Boom! Studios, IDW, Legendary Comics, Zenescope Entertainment, Archie Comics, Disney Publishing, and Sports Illustrated. Past commercial clients have included Warner Brothers Studios, Hasbro Toys, Mattel Toys, Paramount Studios, and Walt Disney Studios. Drew is best known for his recent work on Legendary Comics’ best-selling graphic novel, GODZILLA: AFTERSHOCK, as well as for his work as series illustrator on DC Comics’ WONDER WOMAN, SUPERGIRL and THE AUTHORITY. In 2013, Drew moved into the field of television animation, working as a Storyboard Revisionist for two episodes of Marvel Animantion’s series, HULK & THE AGENTS OF SMASH. Drew’s other animation works include Storyboard artist on four episodes of Marvel Animation’s series, GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY, season 2, as well as character concept design for Bento Box Entertainment’s shows THE BLUES BROTHERS and BOTCOP in 2016. Over the course of his career, Drew has served as a member of illustration studios such as Jolly Roger Studio, of Macon, GA, as well as Helioscope Studio of Portland, OR. He is currently a member of Garage Art Studio of North Hollywood, CA. Work Experience Freelance Storyboard Artist 2016-Current Responsiblities include working with show director to create storyboard roughs and clean-ups using Toon Boom Storyboard Pro 4.1, and creating PDF files of rough and clean boards as well as track-timed animatic Quicktime movies. -

Teleseries.Cl 2,736 Likes

Inicio Nosotros Entrevistas Críticas Baúl de Recuerdos Diurnas Vespertinas Nocturnas v i e r n e s , 2 d e j u n i o d e 2 0 1 7 Buscar Series chilenas seleccionadas para exclusivo evento internacional Teleseries.cl 2,736 likes Like Page Share Be the first of your friends to like this Tweets por @TeleseriesCL Reproducción CNTV. LO MÁS LEÍDO DE LA SEMANA Durante el miércoles 21 y el viernes 23 de este mes, en la ciudad de Santiago de Compostela, España, se realizará la primera versión de Convertido de web en PDF a http://www.htmlapdf.com con el api html a pdf Conecta Fiction, evento que aspira a ser el punto de encuentro y TVN define historia de su nueva teleserie y anuncia plataforma de negocio para la coproducción de ficción televisiva entre numeroso elenco Latinoamérica, Estados Unidos de habla hispana y Europa. Gentileza TVN. Como hace bastante no se veía, la vespertina que la señal pública comenzará a grabar en julio A días del encuentro, la organización anunció los diez proyectos para suceder a “La Colombia... seleccionados para el pitching de coproducción internacional de series y miniseries para televisión. Así, entre estos destacan dos proyectos locales. “Lo Que Callamos las Mujeres” Se trata de “Inés del Alma Mía”, miniserie de Chilevisión basada en la estrena nuevo formato en Chilevisión Gentileza Chilevisión. Cuatro novela de Isabel Allende y centrada en la figura de Inés de Suárez, y capítulos darán vida a una historia. “Héroes Invisibles”, coproducción de la televisión pública de Finlandia YLE Así es la nueva propuesta que y la productora nacional Parox que narra la historia de un grupo de presentará la exitosa serie que funcionarios de la embajada de Finlandia que necesita encontrar realiza.. -

This January... Novel Ideas

ILLUMINATIONSNOV 2016 THIS JANUARY... # 338 ANGEL - SEASON 11 KAMANDI CHALLENGE HELLBOY - WINTER SPECIAL PSYCHDRAMA ILLUSTRATED SHERLOCK: BLIND BANKER NOVEL IDEAS ANGEL AND MORE! Deadpool The Duck #1 (Marvel) CONTENTS: PAGE 03... New Series and One-Shots for January: Dark Horse PAGE 04... New Series and One-Shots for January: DC Comics PAGE 05... New Series and One-Shots for January: DC Comics PAGE 06... New Series and One-Shots for January: IDW Publishing PAGE 07... New Series and One-Shots for January: Image Comics PAGE 08... New Series and One-Shots for January: Marvel Comics PAGE 09... New Series and One-Shots for January: Indies PAGE 10... Novel Ideas - Part One PAGE 11... Novel Ideas - Part Two SIGN UP FOR THE PAGE 12... Graphic Novel Top 20: October’s Bestselling Books ACE COMICS MAILOUT AND KEEP UP TO DATE WITH THE LATEST RELEASES, SUBSCRIPTIONS, CHARTS, acecomics.co.uk ILLUMINATIONS, EVENTS For the complete catalogue of new releases visit previews.com/catalog AND MORE! 02 DARK HORSE NEW SERIES AND ONE�SHOTS FOR JANUARY LOBSTER JOHNSON: GARDEN OF BONES ANGEL - (ONE-SHOT) SEASON 11 #1 Mignola, Arcudi, Green, Bechko, Borges, Fischer Zonjic Vampire Angel is tormented by a vision linking When an undead hit man goes after the NYPD, his shameful past to something very big-and the Lobster steps in to figure out if it’s a very bad-that is coming. The goddess Illyria zombie-or something worse. gives Angel some insight and incentive. Then In Shops: 11/01/2017 she really gets involved, and Angel discovers that it might be possible to change the future by changing the past. -

O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE ARQUITETURA E URBANISMO O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Aline Stefânia Zim Brasília - DF 2018 1 ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora em Arquitetura. Área de Pesquisa: Teoria, História e Crítica da Arte Orientador: Prof. Dr. Flávio Rene Kothe Brasília – DF 2018 2 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO DA ARQUITETURA Tese aprovada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora pelo Programa de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de Brasília. Comissão Examinadora: ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Flávio René Kothe (Orientador) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Fernando Freitas Fuão Departamento de Teoria, História e Crítica da Arquitetura – FAU-UFRGS ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Lúcia Helena Marques Ribeiro Departamento de Teoria Literária e Literatura – TEL-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Ana Elisabete de Almeida Medeiros Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Benny Schvarsberg Departamento de Projeto e Planejamento – FAU-UnB Brasília – DF 2018 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a todos que compartilharam de alguma forma esse manifesto. Aos familiares que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança e o respeito. Aos amigos, colegas e alunos que dividiram as inquietações e os dias difíceis, agradeço a presença. Aos que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança. Aos professores, colegas e amigos do Núcleo de Estética, Hermenêutica e Semiótica.