Mckee 1906-1984

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ron Blakey, Publications (Does Not Include Abstracts)

Ron Blakey, Publications (does not include abstracts) The publications listed below were mainly produced during my tenure as a member of the Geology Department at Northern Arizona University. Those after 2009 represent ongoing research as Professor Emeritus. (PDF) – A PDF is available for this paper. Send me an email and I'll attach to return email Blakey, R.C., 1973, Stratigraphy and origin of the Moenkopi Formation of southeastern Utah: Mountain Geologist, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1 17. Blakey, R.C., 1974, Stratigraphic and depositional analysis of the Moenkopi Formation, Southeastern Utah: Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 104, 81 p. Blakey, R.C., 1977, Petroliferous lithosomes in the Moenkopi Formation, Southern Utah: Utah Geology, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 67 84. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Oil impregnated carbonate rocks of the Timpoweap Member Moenkopi Formation, Hurricane Cliffs area, Utah and Arizona: Utah Geology, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 45 54. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Stratigraphy of the Supai Group (Pennsylvanian Permian), Mogollon Rim, Arizona: in Carboniferous Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon Country, northern Arizona and southern Nevada, Field Trip No. 13, Ninth International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology, p. 89 109. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Lower Permian stratigraphy of the southern Colorado Plateau: in Four Corners Geological Society, Guidebook to the Permian of the Colorado Plateau, p. 115 129. (PDF) Blakey, R.C., 1980, Pennsylvanian and Early Permian paleogeography, southern Colorado Plateau and vicinity: in Paleozoic Paleogeography of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, p. 239 258. Blakey, R.C., Peterson, F., Caputo, M.V., Geesaman, R., and Voorhees, B., 1983, Paleogeography of Middle Jurassic continental, shoreline, and shallow marine sedimentation, southern Utah: Mesozoic PaleogeogÂraphy of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section of Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists (Symposium), p. -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

Grand Canyon

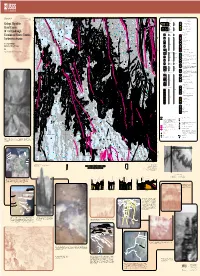

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Subsurface Geologic Plates of Eastern Arizona and Western New Mexico

Implications of Live Oil Shows in an Eastern Arizona Geothermal Test (1 Alpine-Federal) by Steven L. Rauzi Oil and Gas Program Administrator Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 94-1 Version 2.0 June, 2009 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 INTRODUCTION The 1 Alpine-Federal geothermal test, at an elevation of 8,556 feet in eastern Arizona, was drilled by the Arizona Department of Commerce and U.S. Department of Energy to obtain information about the hot-dry-rock potential of Precambrian rocks in the Alpine-Nutrioso area, a region of extensive basaltic volcanism in southern Apache County. The hole reached total depth of 4,505 feet in August 1993. Temperature measurements were taken through October 1993 when final temperature, gamma ray, and neutron logs were run. The Alpine-Federal hole is located just east of U.S. Highway 180/191 (old 180/666) at the divide between Alpine and Nutrioso, in sec. 23, T. 6 N., R. 30 E., in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest (Fig. 1). The town of Alpine is about 6 miles south of the wellsite and the Arizona-New Mexico state line is about 6 miles east. The basaltic Springerville volcanic field is just north of the wellsite (Crumpler, L.S., Aubele, J.C., and Condit, C.D., 1994). Although volcanic rocks of middle Miocene to Oligocene age (Reynolds, 1988) are widespread in the region, erosion has removed them from the main valleys between Alpine and Nutrioso. As a result, the 1 Alpine-Federal was spudded in sedimentary strata of Oligocene to Eocene age (Reynolds, 1988). -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

62. Origin of Horseshoe Bend, Arizona, and the Navajo and Coconino Sandstones, Grand Canyon − Flood Geology Disproved

62. Origin of Horseshoe Bend, Arizona, and the Navajo and Coconino Sandstones, Grand Canyon − Flood Geology Disproved Lorence G. Collins July 1, 2020 Email address: [email protected] Abstract Young-Earth creationists (YEC) claim that Horseshoe Bend in Arizona was carved by the Colorado River soon after Noah's Flood had deposited sedimentary rocks during the year of the Flood about 4,400 years ago. Its receding waters are what entrenched the Colorado River in a U-shaped horseshoe bend. Conventional geology suggests that the Colorado River was once a former meandering river flowing on a broad floodplain, and as tectonic uplift pushed up northern Arizona, the river slowly cut down through the sediments while still preserving its U-shaped bend. Both the Jurassic Navajo Sandstone at Horseshoe Bend, and the underlying Permian Coconino Sandstone exposed in the Grand Canyon, are claimed by YECs to be deposited by Noah's Flood while producing underwater, giant, cross-bedded dunes. Conventional geology interprets that these cross-bedded dunes were formed in a desert environment by blowing wind. Evidence is presented in this article to show examples of features that cannot be explained by the creationists' Flood geology model. Introduction The purpose of this article is two-fold. The first is to demonstrate that the physical features of the Navajo and Coconino sandstones at Horseshoe Bend and in the Grand Canyon National Park are best understood by contemporary geology as aeolian sand dunes deposited by blowing wind. The second is to describe how Horseshoe Bend and the Grand Canyon were formed by the Colorado River slowly meandering across a flat floodplain and eroding the Bend and the Canyon over a few million years as plate tectonic forces deep in the earth’s crust uplifted northern Arizona and southern Utah. -

The Supai Group Subdivision and Nomenclature

GrOLOGY L BRARt] C;EP 3 1 «'5 The Supai Group Subdivision and Nomenclature GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1395-J The Supai Group Subdivision and Nomenclature By EDWIN D. McKEE CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1395-J The Supai Formation of the Grand Canyon region is raised in rank to Supai Group and divided into four formations that range in age from Early Pennsylvanian to Early Permian UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1975 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data McKee, Edwin Dinwiddie, 1906- The Supai Group Subdivision and nomenclature. (Contributions to stratigraphy) (Geological Survey Bulletin 1395-J) Bibliography: p. Supt.ofDocs.no.: 119.3:1395-1 1. Geology, Stratigraphic-Permian. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic-Pennsylvanian. 3. Geology, Stratigraphic Nomenclature Arizona Grand Canyon region. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: United States Geological Survey Bulletin 139S-J QE75.B9 No. 1395-J [QE674] 557.3'08s [551.7'52'0979132] 75-619022 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington, D. C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-02656-2 CONTENTS Page Abstract........................................................................................................................... Jl Introduction: field terminology and new nomenclature............................................... 1 Watahomigi Formation................................................................................................. -

Climatic and Tectonic Controls on Jurassic Intra-Arc Basins Related to Northward Drift of North America

spe393-13 page 359 Geological Society of America Special Paper 393 2005 Climatic and tectonic controls on Jurassic intra-arc basins related to northward drift of North America Cathy J. Busby* Department of Geological Sciences, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106, USA Kari Bassett* Department of Geological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Maureen B. Steiner* Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming 82071, USA Nancy R. Riggs* Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA ABSTRACT Upper Jurassic strike-slip intra-arc basins formed along the axis of earlier Lower to Middle Jurassic extensional intra-arc basins in Arizona. These strike-slip basins developed along the Sawmill Canyon fault zone, which may represent an inboard strand of the Mojave-Sonora megashear system that did not necessarily produce large-scale translations. Subsidence in the Lower to Middle Jurassic extensional arc was uniformly fast and continuous, whereas at least parts of the Upper Jurassic arc experienced rapidly alternating uplift and subsidence, producing numerous large-scale intrabasinal unconformities. Volcanism occurred only at releasing bends or stepovers in the Upper Jurassic arc, producing more episodic and localized eruptions than in the earlier extensional arc. Sediment sources in the Upper Jurassic strike-slip arc were also more localized, with restraining bends shedding sediment into nearby releasing bends. Normal fault scarps were rapidly buried by voluminous pyroclastic debris in the Lower to Middle Jurassic extensional arc, so epiclastic sedimentary deposits are rare, whereas pop-up structures in the Upper Jurassic strike-slip arc shed abundant epiclastic sedi- ment into the basins. -

Cenozoic Stratigraphy and Paleogeography of the Grand Canyon, AZ Amanda D'el

Pre-Cenozoic Stratigraphy and Paleogeography of the Grand Canyon, AZ Amanda D’Elia Abstract The Grand Canyon is a geologic wonder offering a unique glimpse into the early geologic history of the North American continent. The rock record exposed in the massive canyon walls reveals a complex history spanning more than a Billion years of Earth’s history. The earliest known rocks of the Southwestern United States are found in the Basement of the Grand Canyon and date Back to 1.84 Billion years old (Ga). The rocks of the Canyon can Be grouped into three distinct sets Based on their petrology and age (Figure 1). The oldest rocks are the Vishnu Basement rocks exposed at the Base of the canyon and in the granite gorges. These rocks provide a unique clue as to the early continental formation of North America in the early PrecamBrian. The next set is the Grand Canyon Supergroup, which is not well exposed throughout the canyon, But offers a glimpse into the early Beginnings of Before the CamBrian explosion. The final group is the Paleozoic strata that make up the Bulk of the Canyon walls. Exposure of this strata provides a detailed glimpse into North American environmental changes over nearly 300 million years (Ma) of geologic history. Together these rocks serve not only as an awe inspiring Beauty But a unique opportunity to glimpse into the past. Vishnu Basement Rocks The oldest rocks exposed within the Grand Canyon represent some of the earliest known rocks in the American southwest. John Figure 1. Stratigraphic column showing Wesley Paul referred to them as the “dreaded the three sets of rocks found in the Grand rock” Because they make up the walls of some Canyon, their thickness and approximate of the quickest and most difficult rapids to ages (Mathis and Bowman, 2006). -

Fracture History of the Redwall Limestone and Lower Supai Group, Western Hualapai Indian Reservation, Northwestern Arizona

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Fracture history of the Redwall Limestone and lower Supai Group, western Hualapai Indian Reservation, northwestern Arizona by Julie A. Roller Open-File Report 87- 359 Prepared in cooperation with the Hualapai Indian Reservation This report was prepared under contract to the U.S. Geological Survey and has not been reviewed for conformity with USGS editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Opinions and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the USGS. (Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the USGS.) (Released in response to a Freedom of Information Act request.) 1 RR 12 Box 90-D3 Flagstaff, AZ. 86001 1987 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.... 1 Methods ......... 3 Fracture pattern 3 Fracture sets of the Redwall Limestone. ........ 5- Fracture set 1 (Fl)... ................... .. 7 Fracture set 2 (F2). ....................... 7 Fracture set (F3)................ ........ 12 Fracture set (F4). ....................... 12 Fracture set (F5).......... .............. 12 Fracture set (F6). ....................... 17 Fracture set (F7)........................ 17 Fracture sets of the Surprise Canyon Formation, 17 Fracture sets of the Supai Group............... 17 Fracture set 3 (F3) ....................... 18 Fracture set (F4) ....................... 18 Fracture set (F5) ....................... 18 Fracture set (F6) ....................... 18 Fracture set (F7) ....................... 23 Fractures that cut -

The Long and Extraordinary History of Life in Our Office Christa Sadler GTS 2006/March 25

LIFE IN STONE: The Long and Extraordinary History of Life in Our Office Christa Sadler GTS 2006/March 25 PRECAMBRIAN (4.6 billion to 544 million years ago) • Life on Earth begins about 3.5 billion years ago: single-celled bacteria that often form stromatolites (later, when true algae evolves, it also form stromatolites). The earliest life in Grand Canyon is about 1.2 billion years old, in the Bass Formation of the GC Supergroup. Several of the Supergroup layers have stromatolites in them, most made of true algae. There are several species known in Grand Canyon, ranging in size from a few inches high to several tens of feet long. Multicellular life appeared about 700 million years ago, and may have been present in some of the later Chuar Group sediments, but the evidence is sketchy at best. PALEOZOIC Cambrian (544 to 490 million years ago) Tapeats, Bright Angel, Muav) • The “Cambrian Explosion” in the early part of the Cambrian saw the beginnings of all the major groups of animals alive today. This diversification of life may have taken as little as five million years, which is, trust me, a really short time, geologically speaking. • The Cambrian seas were dominated by animals that were filter feeders, that is, little bulldozers that dug food out of the sediment. We see evidence of this in the Tapeats Sandstone and Bright Angel Shale, where worm burrows and trilobite tracks are really common. There are some 40 species of trilobites in Grand Canyon, but none of them are all that well preserved. At the time of the Tapeats/BA/Muav, there was no life on land, although there are some things found in the Bright Angel that some researchers interpret as spores from land plants.