72. Two Early Basal-Amniote Fossil Trackways in Eolian Dune Sandstone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ron Blakey, Publications (Does Not Include Abstracts)

Ron Blakey, Publications (does not include abstracts) The publications listed below were mainly produced during my tenure as a member of the Geology Department at Northern Arizona University. Those after 2009 represent ongoing research as Professor Emeritus. (PDF) – A PDF is available for this paper. Send me an email and I'll attach to return email Blakey, R.C., 1973, Stratigraphy and origin of the Moenkopi Formation of southeastern Utah: Mountain Geologist, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1 17. Blakey, R.C., 1974, Stratigraphic and depositional analysis of the Moenkopi Formation, Southeastern Utah: Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 104, 81 p. Blakey, R.C., 1977, Petroliferous lithosomes in the Moenkopi Formation, Southern Utah: Utah Geology, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 67 84. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Oil impregnated carbonate rocks of the Timpoweap Member Moenkopi Formation, Hurricane Cliffs area, Utah and Arizona: Utah Geology, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 45 54. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Stratigraphy of the Supai Group (Pennsylvanian Permian), Mogollon Rim, Arizona: in Carboniferous Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon Country, northern Arizona and southern Nevada, Field Trip No. 13, Ninth International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology, p. 89 109. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Lower Permian stratigraphy of the southern Colorado Plateau: in Four Corners Geological Society, Guidebook to the Permian of the Colorado Plateau, p. 115 129. (PDF) Blakey, R.C., 1980, Pennsylvanian and Early Permian paleogeography, southern Colorado Plateau and vicinity: in Paleozoic Paleogeography of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, p. 239 258. Blakey, R.C., Peterson, F., Caputo, M.V., Geesaman, R., and Voorhees, B., 1983, Paleogeography of Middle Jurassic continental, shoreline, and shallow marine sedimentation, southern Utah: Mesozoic PaleogeogÂraphy of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section of Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists (Symposium), p. -

Fossil Footprints from the Grand Canyon

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 77, NUMBER 9 FOSSIL FOOTPRINTS FROlVI THE GRAND CANYON (WITH TWELVE PLATES) BY CHARLES W. GILMORE Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology, United States National Museum (PUBLICATION 2832) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION JANUARY 30, 1926 6t £or� ��ftimou (Vrtu BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A. FOSSIL FOOTPRINTS FROM THE GRAND CANYON BY CHARLES W. GILMORE CURATOR OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY, UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM WITH !2 PLATES INTRODUCTION Tracks of extinct quadrupeds were first discovered in the Grand Canyon in 1915 by Prof. Charles Schuchert, and specimens collected by him at that time were made the basis of a short paper by Dr. R. S. Lull1 in which were described two species, Laoporus schucherti and L. nobeli, from the Coconino sandstone. In the summer of 1924, the locality was visited by Dr. John C. Merriam, president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who made a small collection of tracks which were later presented to the United States National Museum. While at the locality, Doctor Mer riam conceived the idea of having a permanent exhibit of these foot prints in situ on the Hermit Trail, to teach a lesson as to the great antiquity of the animal life that once roamed over these ancient sands-a lesson that could not fail to be understood by the veriest tyro in geological phenomena. This plan was presented to Hon. Stephen F. Mather, director of the National Park Service, who im mediately became interested in the project, and, with the aid of friends of the Park Service, arrangements were perfected whereby, in the late fall of 1924, the writer was detailed to visit the locality and prepare such an exhibit, and at the same time to make a col lection of the footprints for the United States National Museum. -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

Grand Canyon

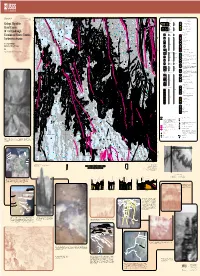

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Subsurface Geologic Plates of Eastern Arizona and Western New Mexico

Implications of Live Oil Shows in an Eastern Arizona Geothermal Test (1 Alpine-Federal) by Steven L. Rauzi Oil and Gas Program Administrator Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 94-1 Version 2.0 June, 2009 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 INTRODUCTION The 1 Alpine-Federal geothermal test, at an elevation of 8,556 feet in eastern Arizona, was drilled by the Arizona Department of Commerce and U.S. Department of Energy to obtain information about the hot-dry-rock potential of Precambrian rocks in the Alpine-Nutrioso area, a region of extensive basaltic volcanism in southern Apache County. The hole reached total depth of 4,505 feet in August 1993. Temperature measurements were taken through October 1993 when final temperature, gamma ray, and neutron logs were run. The Alpine-Federal hole is located just east of U.S. Highway 180/191 (old 180/666) at the divide between Alpine and Nutrioso, in sec. 23, T. 6 N., R. 30 E., in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest (Fig. 1). The town of Alpine is about 6 miles south of the wellsite and the Arizona-New Mexico state line is about 6 miles east. The basaltic Springerville volcanic field is just north of the wellsite (Crumpler, L.S., Aubele, J.C., and Condit, C.D., 1994). Although volcanic rocks of middle Miocene to Oligocene age (Reynolds, 1988) are widespread in the region, erosion has removed them from the main valleys between Alpine and Nutrioso. As a result, the 1 Alpine-Federal was spudded in sedimentary strata of Oligocene to Eocene age (Reynolds, 1988). -

Grand Canyon Archaeological Site

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY For Colorado River Commercial Operators This etiquette policy was developed as a preservation tool to protect archaeological sites along the Colorado River. This policy classifies all known archaeological sites into one of four classes and helps direct visitors to sites that can withstand visitation and to minimize impacts to those that cannot. Commercially guided groups may visit Class I and Class II sites; however, inappropriate behaviors and activities on any archaeological site is a violation of federal law and Commercial Operating Requirements. Class III sites are not appropriate for visitation. National Park Service employees and Commercial Operators are prohibited from disclosing the location and nature of Class III archaeological sites. If clients encounter archaeological sites in the backcountry, guides should take the opportunity to talk about ancestral use of the Canyon, discuss the challenges faced in protecting archaeological resources in remote places, and reaffirm Leave No Trace practices. These include observing from afar, discouraging clients from collecting site coordinates and posting photographs and maps with location descriptions on social media. Class IV archaeological sites are closed to visitation; they are listed on Page 2 of this document. Commercial guides may share the list of Class I, Class II and Class IV sites with clients. It is the responsibility of individual Commercial Operators to disseminate site etiquette information to all company employees and to ensure that their guides are teaching this information to all clients prior to visiting archaeological sites. Class I Archaeological Sites: Class I sites have been Class II Archaeological Sites: Class II sites are more managed specifically to withstand greater volumes of vulnerable to visitor impacts than Class I sites. -

South Kaibab Trail, Grand Canyon

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona South Kaibab Trail Hikers seeking panoramic views unparalleled on any other trail at Grand Canyon will want to consider a hike down the South Kaibab Trail. It is the only trail at Grand Canyon National Park that so dramatically holds true to a ridgeline descent. But this exhilarating sense of exposure to the vastness of the canyon comes at a cost: there is little shade and no water for the length of this trail. During winter months, the constant sun exposure is likely to keep most of the trail relatively free of ice and snow. For those who insist on hiking during summer months, which is not recommended in general, this trail is the quickest way to the bottom (it has been described as "a trail in a hurry to get to the river"), but due to lack of any water sources, ascending the trail can be a dangerous proposition. The South Kaibab Trail is a modern route, having been constructed as a means by which park visitors could bypass Ralph Cameron's Bright Angel Trail. Cameron, who owned the Bright Angel Trail and charged a toll to those using it, fought dozens of legal battles over several decades to maintain his personal business rights. These legal battles inspired the Santa Fe Railroad to build its own alternative trail, the Hermit Trail, beginning in 1911 before the National Park Service went on to build the South Kaibab Trail beginning in 1924. In this way, Cameron inadvertently contributed much to the greater network of trails currently available for use by canyon visitors. -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

Chapter 9. Paleozoic Vertebrate Ichnology of Grand Canyon National Park

Chapter 9. Paleozoic Vertebrate Ichnology of Grand Canyon National Park By Lorenzo Marchetti1, Heitor Francischini2, Spencer G. Lucas3, Sebastian Voigt1, Adrian P. Hunt4, and Vincent L. Santucci5 1Urweltmuseum GEOSKOP / Burg Lichtenberg (Pfalz) Burgstraße 19 D-66871 Thallichtenberg, Germany 2Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) Laboratório de Paleontologia de Vertebrados and Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, Instituto de Geociências Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 3New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science 1801 Mountain Road N.W. Albuquerque, New Mexico, 87104 4Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum 3407 109th St SW Everett, Washington 98204 5National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 Introduction Vertebrate tracks are the only fossils of terrestrial vertebrates known from Paleozoic strata of Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA), therefore they are of great importance for the reconstruction of the extinct faunas of this area. For more than 100 years, the upper Paleozoic strata of the Grand Canyon yielded a noteworthy vertebrate track collection, in terms of abundance, completeness and quality of preservation. These are key requirements for a classification of tracks through ichnotaxonomy. This chapter proposes a complete ichnotaxonomic revision of the track collections from GRCA and is also based on a large amount of new material. These Paleozoic tracks were produced by different tetrapod groups, such as eureptiles, parareptiles, synapsids and anamniotes, and their size ranges from 0.5 to 20 cm (0.2 to 7.9 in) footprint length. As the result of the irreversibility of the evolutionary process, they provide useful information about faunal composition, faunal events, paleobiogeographic distribution and biostratigraphy. -

Sessions Calendar

Associated Societies GSA has a long tradition of collaborating with a wide range of partners in pursuit of our mutual goals to advance the geosciences, enhance the professional growth of society members, and promote the geosciences in the service of humanity. GSA works with other organizations on many programs and services. AASP - The American Association American Geophysical American Institute American Quaternary American Rock Association for the Palynological Society of Petroleum Union (AGU) of Professional Association Mechanics Association Sciences of Limnology and Geologists (AAPG) Geologists (AIPG) (AMQUA) (ARMA) Oceanography (ASLO) American Water Asociación Geológica Association for Association of Association of Earth Association of Association of Geoscientists Resources Association Argentina (AGA) Women Geoscientists American State Science Editors Environmental & Engineering for International (AWRA) (AWG) Geologists (AASG) (AESE) Geologists (AEG) Development (AGID) Blueprint Earth (BE) The Clay Minerals Colorado Scientifi c Council on Undergraduate Cushman Foundation Environmental & European Association Society (CMS) Society (CSS) Research Geosciences (CF) Engineering Geophysical of Geoscientists & Division (CUR) Society (EEGS) Engineers (EAGE) European Geosciences Geochemical Society Geologica Belgica Geological Association Geological Society of Geological Society of Geological Society of Union (EGU) (GS) (GB) of Canada (GAC) Africa (GSAF) Australia (GSAus) China (GSC) Geological Society of Geological Society of Geologische Geoscience -

Chertification of the Redwall Limestone (Mississippian), Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

Chertification of the Redwall limestone (Mississippian), Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hess, Alison Anne Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 09:46:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/558024 CHERTIFICATION OF THE REDWALL LIMESTONE (MISSISSIPPIAN), GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK, ARIZONA by Alison Anne Hess A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES * In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 8 5 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author.