Dakoterra Volume 5 . October 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ron Blakey, Publications (Does Not Include Abstracts)

Ron Blakey, Publications (does not include abstracts) The publications listed below were mainly produced during my tenure as a member of the Geology Department at Northern Arizona University. Those after 2009 represent ongoing research as Professor Emeritus. (PDF) – A PDF is available for this paper. Send me an email and I'll attach to return email Blakey, R.C., 1973, Stratigraphy and origin of the Moenkopi Formation of southeastern Utah: Mountain Geologist, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1 17. Blakey, R.C., 1974, Stratigraphic and depositional analysis of the Moenkopi Formation, Southeastern Utah: Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 104, 81 p. Blakey, R.C., 1977, Petroliferous lithosomes in the Moenkopi Formation, Southern Utah: Utah Geology, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 67 84. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Oil impregnated carbonate rocks of the Timpoweap Member Moenkopi Formation, Hurricane Cliffs area, Utah and Arizona: Utah Geology, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 45 54. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Stratigraphy of the Supai Group (Pennsylvanian Permian), Mogollon Rim, Arizona: in Carboniferous Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon Country, northern Arizona and southern Nevada, Field Trip No. 13, Ninth International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology, p. 89 109. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Lower Permian stratigraphy of the southern Colorado Plateau: in Four Corners Geological Society, Guidebook to the Permian of the Colorado Plateau, p. 115 129. (PDF) Blakey, R.C., 1980, Pennsylvanian and Early Permian paleogeography, southern Colorado Plateau and vicinity: in Paleozoic Paleogeography of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, p. 239 258. Blakey, R.C., Peterson, F., Caputo, M.V., Geesaman, R., and Voorhees, B., 1983, Paleogeography of Middle Jurassic continental, shoreline, and shallow marine sedimentation, southern Utah: Mesozoic PaleogeogÂraphy of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section of Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists (Symposium), p. -

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

Tetrapod Biostratigraphy and Biochronology of the Triassic–Jurassic Transition on the Southern Colorado Plateau, USA

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 244 (2007) 242–256 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Triassic–Jurassic transition on the southern Colorado Plateau, USA Spencer G. Lucas a,⁎, Lawrence H. Tanner b a New Mexico Museum of Natural History, 1801 Mountain Rd. N.W., Albuquerque, NM 87104-1375, USA b Department of Biology, Le Moyne College, 1419 Salt Springs Road, Syracuse, NY 13214, USA Received 15 March 2006; accepted 20 June 2006 Abstract Nonmarine fluvial, eolian and lacustrine strata of the Chinle and Glen Canyon groups on the southern Colorado Plateau preserve tetrapod body fossils and footprints that are one of the world's most extensive tetrapod fossil records across the Triassic– Jurassic boundary. We organize these tetrapod fossils into five, time-successive biostratigraphic assemblages (in ascending order, Owl Rock, Rock Point, Dinosaur Canyon, Whitmore Point and Kayenta) that we assign to the (ascending order) Revueltian, Apachean, Wassonian and Dawan land-vertebrate faunachrons (LVF). In doing so, we redefine the Wassonian and the Dawan LVFs. The Apachean–Wassonian boundary approximates the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. This tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Triassic–Jurassic transition on the southern Colorado Plateau confirms that crurotarsan extinction closely corresponds to the end of the Triassic, and that a dramatic increase in dinosaur diversity, abundance and body size preceded the end of the Triassic. © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Triassic–Jurassic boundary; Colorado Plateau; Chinle Group; Glen Canyon Group; Tetrapod 1. Introduction 190 Ma. On the southern Colorado Plateau, the Triassic– Jurassic transition was a time of significant changes in the The Four Corners (common boundary of Utah, composition of the terrestrial vertebrate (tetrapod) fauna. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

Triassic Stratigraphy of the Southeastern Colorado Plateau, West-Central New Mexico Spencer G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: https://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/72 Triassic stratigraphy of the southeastern Colorado Plateau, west-central New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, 2021, pp. 229-240 in: Geology of the Mount Taylor area, Frey, Bonnie A.; Kelley, Shari A.; Zeigler, Kate E.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Goff, Fraser; Ulmer-Scholle, Dana S., New Mexico Geological Society 72nd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 310 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2021 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, Color Plates, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Mesozoic Stratigraphy at Durango, Colorado

160 New Mexico Geological Society, 56th Field Conference Guidebook, Geology of the Chama Basin, 2005, p. 160-169. LUCAS AND HECKERT MESOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY AT DURANGO, COLORADO SPENCER G. LUCAS AND ANDREW B. HECKERT New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 1801 Mountain Rd. NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104 ABSTRACT.—A nearly 3-km-thick section of Mesozoic sedimentary rocks is exposed at Durango, Colorado. This section con- sists of Upper Triassic, Middle-Upper Jurassic and Cretaceous strata that well record the geological history of southwestern Colorado during much of the Mesozoic. At Durango, Upper Triassic strata of the Chinle Group are ~ 300 m of red beds deposited in mostly fluvial paleoenvironments. Overlying Middle-Upper Jurassic strata of the San Rafael Group are ~ 300 m thick and consist of eolian sandstone, salina limestone and siltstone/sandstone deposited on an arid coastal plain. The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation is ~ 187 m thick and consists of sandstone and mudstone deposited in fluvial environments. The only Lower Cretaceous strata at Durango are fluvial sandstone and conglomerate of the Burro Canyon Formation. Most of the overlying Upper Cretaceous section (Dakota, Mancos, Mesaverde, Lewis, Fruitland and Kirtland units) represents deposition in and along the western margin of the Western Interior seaway during Cenomanian-Campanian time. Volcaniclastic strata of the overlying McDermott Formation are the youngest Mesozoic strata at Durango. INTRODUCTION Durango, Colorado, sits in the Animas River Valley on the northern flank of the San Juan Basin and in the southern foothills of the San Juan and La Plata Mountains. Beginning at the northern end of the city, and extending to the southern end of town (from north of Animas City Mountain to just south of Smelter Moun- tain), the Animas River cuts in an essentially downdip direction through a homoclinal Mesozoic section of sedimentary rocks about 3 km thick (Figs. -

Magnetostratigraphy of the Upper Triassic Chinle Group of New Mexico: Implications for Regional and Global Correlations Among Upper Triassic Sequences

Magnetostratigraphy of the Upper Triassic Chinle Group of New Mexico: Implications for regional and global correlations among Upper Triassic sequences Kate E. Zeigler1,* and John W. Geissman2,* 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, MSC 03-2040 Northrop Hall, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131, USA 2Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, MSC 03-2040 Northrop Hall, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131, USA, and Department of Geosciences, ROC 21, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 West Campbell Road, Richardson, Texas 75080-3021, USA ABSTRACT polarity chronologies from upper Chinle graphic correlations (e.g., Reeve, 1975; Reeve and strata in New Mexico and Utah suggest that Helsley, 1972; Bazard and Butler, 1989, 1991; A magnetic polarity zonation for the strata considered to be part of the Rock Point Molina-Garza et al., 1991, 1993, 1996, 1998a, Upper Triassic Chinle Group in the Chama Formation in north-central New Mexico are 1998b, 2003; Steiner and Lucas, 2000). Conse- Basin, north-central New Mexico (United not time equivalent to type Rock Point strata quently, the polarity record of the mudstones and States), supplemented by polarity data from in Utah or to the Redonda Formation of east- claystones, which are the principal rock types in eastern and west-central New Mexico (Mesa ern New Mexico. the Chinle Group, is largely unknown. Redonda and Zuni Mountains, respectively), In our study of Triassic strata in the Chama provides the most complete and continuous INTRODUCTION Basin of north-central New Mexico, we sam- magnetic polarity chronology for the Late pled all components of the Chinle Group, with Triassic of the American Southwest yet avail- The Upper Triassic Chinle Group, prominent a focus on mudstones and claystones at Coyote able. -

Geologic Story of Canyonlands National Park

«u GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1327 JUL 1 7 1990 Dacus Library Wmthrop College Documents Department -T7 LOOKING NORTH FROM EAST WALL OF DEVILS LANE, just south of the Silver Stairs. Needles are Cedar Mesa Sandstone. Junction Butte and Grand View Point lie across Colorado River in background. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1327 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-600043 Reprinted 1977 and 1990 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1974 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 . Contents Page A new park is born 1 Major Powell's river expeditions 4 Early history 9 Prehistoric people 9 Late arrivals 14 Geographic setting 17 Rocks and landforms 20 How to see the park 26 The high mesas 27 Island in the Sky 27 Dead Horse Point State Park 30 North entrance 34 Shafer and White Rim Trails 34 Grand View Point 36 Green River Overlook 43 Upheaval Dome 43 Hatch Point 46 Needles Overlook 47 Canyonlands Overlook 48 U-3 Loop 49 Anticline Overlook 50 Orange Cliffs 54 The benchlands 5g The Maze and Land of Standing Rocks 58 The Needles district 60 Salt, Davis, and Lavender Canyons _ 64 The Needles and The Grabens 73 Canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers 85 Entrenched and cutoff meanders 86 Green River 87 Colorado River _ 96 Summary of geologic history H2 Additional reading H7 Acknowledgments H8 Selected references n% Index 123 VII Illustrations Page Frontispiece . -

Grand Canyon

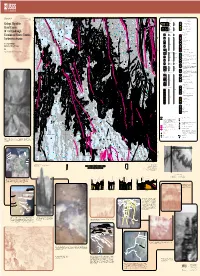

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Subsurface Geologic Plates of Eastern Arizona and Western New Mexico

Implications of Live Oil Shows in an Eastern Arizona Geothermal Test (1 Alpine-Federal) by Steven L. Rauzi Oil and Gas Program Administrator Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 94-1 Version 2.0 June, 2009 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 INTRODUCTION The 1 Alpine-Federal geothermal test, at an elevation of 8,556 feet in eastern Arizona, was drilled by the Arizona Department of Commerce and U.S. Department of Energy to obtain information about the hot-dry-rock potential of Precambrian rocks in the Alpine-Nutrioso area, a region of extensive basaltic volcanism in southern Apache County. The hole reached total depth of 4,505 feet in August 1993. Temperature measurements were taken through October 1993 when final temperature, gamma ray, and neutron logs were run. The Alpine-Federal hole is located just east of U.S. Highway 180/191 (old 180/666) at the divide between Alpine and Nutrioso, in sec. 23, T. 6 N., R. 30 E., in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest (Fig. 1). The town of Alpine is about 6 miles south of the wellsite and the Arizona-New Mexico state line is about 6 miles east. The basaltic Springerville volcanic field is just north of the wellsite (Crumpler, L.S., Aubele, J.C., and Condit, C.D., 1994). Although volcanic rocks of middle Miocene to Oligocene age (Reynolds, 1988) are widespread in the region, erosion has removed them from the main valleys between Alpine and Nutrioso. As a result, the 1 Alpine-Federal was spudded in sedimentary strata of Oligocene to Eocene age (Reynolds, 1988). -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

Chapter 9. Paleozoic Vertebrate Ichnology of Grand Canyon National Park

Chapter 9. Paleozoic Vertebrate Ichnology of Grand Canyon National Park By Lorenzo Marchetti1, Heitor Francischini2, Spencer G. Lucas3, Sebastian Voigt1, Adrian P. Hunt4, and Vincent L. Santucci5 1Urweltmuseum GEOSKOP / Burg Lichtenberg (Pfalz) Burgstraße 19 D-66871 Thallichtenberg, Germany 2Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) Laboratório de Paleontologia de Vertebrados and Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, Instituto de Geociências Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 3New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science 1801 Mountain Road N.W. Albuquerque, New Mexico, 87104 4Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum 3407 109th St SW Everett, Washington 98204 5National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 Introduction Vertebrate tracks are the only fossils of terrestrial vertebrates known from Paleozoic strata of Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA), therefore they are of great importance for the reconstruction of the extinct faunas of this area. For more than 100 years, the upper Paleozoic strata of the Grand Canyon yielded a noteworthy vertebrate track collection, in terms of abundance, completeness and quality of preservation. These are key requirements for a classification of tracks through ichnotaxonomy. This chapter proposes a complete ichnotaxonomic revision of the track collections from GRCA and is also based on a large amount of new material. These Paleozoic tracks were produced by different tetrapod groups, such as eureptiles, parareptiles, synapsids and anamniotes, and their size ranges from 0.5 to 20 cm (0.2 to 7.9 in) footprint length. As the result of the irreversibility of the evolutionary process, they provide useful information about faunal composition, faunal events, paleobiogeographic distribution and biostratigraphy.