Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME UD 032 911 Thinking About & Accessing Policy Related to Addressing Barriers to Learning. Technical Assistanc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 430 068 UD 032 911 TITLE Thinking about & Accessing Policy Related to Addressing Barriers to Learning. Technical Assistance Sampler. INSTITUTION California Univ., Los Angeles. Center for Mental Health in Schools. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Washington, DC. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. PUB DATE 1998-02-23 NOTE 47p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Change; *Educational Policy; Educational Practices; *Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *Learning; Program Development; Program Implementation IDENTIFIERS *Reform Efforts ABSTRACT This "sampler" package has been developed to provide immediate information on resources related to educational policy related to addressing barriers to learning. The first section lists 69 resources for information about educational improvement and learning, including ERIC. The second section lists 14 print resources for facts relevant to showing policy need. Section 3 lists guides and model programs, including some state initiatives relevant to addressing barriers to learning. Section 4 lists agencies and resource centers that focus on policy concerns or offer resources for the study and formulation of policy. Section 5 lists Web sites related to educational policy, and the sixth section describes the three major resources from the Center: documents from the Clearinghouse, the consultation cadre, and center staff. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9316162 The relation of children’s everyday stressors to parental stress Gustafson, Yvonne Elaine, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1993 UMI 300 N. -

ABSTRACT AHERN, LISA SENATORE. Psychometric

ABSTRACT AHERN, LISA SENATORE. Psychometric Properties of the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form. (Under the direction of Mary Haskett.) Psychometric properties of the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form were investigated using a heterogeneous sample of 185 mothers and fathers of children between the ages of 4- 10 years. The Difficult Child and Parent Distress subscales, as well as Total PSI-SF, were found to be internally consistent. Confirmatory factor analysis did not reveal support for a three-factor model. Results were mixed in terms of support for convergent and discriminant validity. The PSI-SF Total and subscales were related to measures of parent psychopathology and perceptions of child adjustment, but not to observed parent and child behavior. Implications of these findings and suggestions for future research are discussed. PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES OF THE PARENTING STRESS INDEX – SHORT FORM by LISA SENATORE AHERN A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Raleigh 2004 APPROVED BY: ________________________________ Chair of Advisory Committee _______________________________ _______________________________ Psychometric ii DEDICATION To my parents, Mary Grace and John Senatore, who always taught me that I could be anything I wanted to be and do anything I set my mind to, and to my husband, David, whose love and support made this paper possible. Psychometric iii BIOGRAPHY Lisa Ann Senatore Ahern was born November 4, 1978 in Edison, NJ. She is the daughter of John and Mary Grace Senatore and the sister of Michael Senatore. -

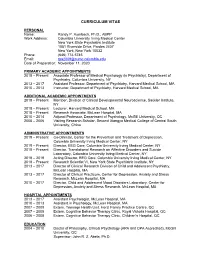

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE PERSONAL Name: Randy P. Auerbach, Ph.D., ABPP Work Address: Columbia University Irving Medical Center New York State Psychiatric Institute 1051 Riverside Drive, Pardes 2407 New York, New York 10032 Phone: (646) 774-5745 Email: [email protected] Date of Preparation: November 11, 2020 PRIMARY ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2018 – Present Associate Professor of Medical Psychology (in Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, NY 2013 – 2017 Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, MA 2010 – 2013 Instructor, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, MA ADDITIONAL ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2018 – Present Member, Division of Clinical Developmental Neuroscience, Sackler Institute, NY 2018 – Present Lecturer, Harvard Medical School, MA 2018 – Present Research Associate, McLean Hospital, MA 2010 – 2014 Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychology, McGill University, QC 2005 – 2006 Visiting Research Scholar, Second Xiangya Medical College of Central South University, China ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS 2019 – Present Co-Director, Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2019 – Present Director, EEG Core, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2018 – Present Director, Translational Research on Affective Disorders and Suicide Laboratory, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2018 – 2019 Acting Director, EEG Core, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2018 – Present Research Scientist VI, New York State -

University of Nevada, Reno Parent Stress and ASD Severity

University of Nevada, Reno Parent Stress and ASD Severity: A Re-Examination A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Psychology by Kimberly J. Loudermilk Dr. Patrick M. Ghezzi/Thesis Advisor May, 2021 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Kimberly Loudermilk entitled Parent Stress and ASD Severity: A Re-examination be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Patrick M. Ghezzi Ph. D Advisor Matthew Lewon Ph. D Co mmittee Member Maryann Demchak Ph. D Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph. D., Dean Graduate School May 2021 i Abstract The purpose of the present research was to investigate the relationship between ASD severity, as assessed by GARS, and parent stress, as assessed by the PSI and the PSI Parent Domain subscales in particular. Studies suggest that parent stress rises to the severity of a young child’s ASD for reasons related to the challenges of parenting and managing severe autistic behavior compared to moderate or mild levels. The participants were parents seeking Early Intensive Behavior Intervention (EIBI) services from a university-based program between 1996 and 2018. A total of 46 mothers and fathers (23 mothers, 23 fathers) and their respective 23 children participated. The present results suggest that a young child with mild ASD ma enable his parents the luxury of spending less time, effort and worry about managing behavior, leaving more time to spend instead on either their own well-being, and/or learning how to manage their child’s behavior more effectively. -

Branching out and Reaching Deeper

The Strengthening Families Approach and Protective Factors Framework: Branching Out and Reaching Deeper n CHARLYN HARPER BROWNE, PhD n SEPTEMBer 2014 The Strengthening Families Approach and Protective Factors Framework: Branching Out and Reaching Deeper © 2014, Center for the Study of Social Policy The Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP) works to secure equal opportunities and better futures for all children and families, especially those most often left behind. Underlying all of the work is a vision of child, family, and community well-being. It’s a unifying framework for the many policy, systems reform, and community change activities in which CSSP engages. Center for the Study of Social Policy 1575 Eye Street, Suite 500 50 Broadway Suite 1504 Washington, DC 20005 New York, NY10004 202.371.1565 telephone 212.979.2369 telephone 202.371.1472 fax 212.995.8756 fax www.cssp.org Acknowledgment The author gratefully acknowledges the help of the following individuals in review of this report: Judy Langford, Nilofer Ahsan, and Cailin O’Connor, colleagues with the Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP), and Juanita Blount-Clark, Anna Lovejoy, and Vicky Marchand, senior consultants with CSSP. This report is in the public domain. Permission to reproduce is not necessary. Suggested citation: Harper Browne, C. (2014, September). The Strengthening Families Approach and Protective Factors Framework: Branching out and reaching deeper. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Social Policy. This report and other documents about the Strengthening Families Approach and Protective Factors Framework are available at www.cssp.org/reform/strengthening-families. Contents n n n Background ..................................................................................................................................... -

Parents' Experience Raising a Child with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Parents' Experience Raising a Child with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) by Charlotte Dianne Strahm B.S.N., Valparaiso University, 1991 M.S.N., Valparaiso University, 1995 Submitted to Rush University in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Nursing Science (c) Copyright by Charlotte Dianne Strahm, 2008 All Rights Reserved ii DISSERTATION APPROVAL FORM The undersigned have examined the dissertation entitled: Parents' Experience Raising a Child with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) presented by: Charlotte Dianne Strahm a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Nursing Science and hereby Certify that in their judgment it is worthy of acceptance. Deborah Gross (Chairperson) 5-13-08 Kathleen Delaney Professor Associate Professor College of Nursing College of Nursing Rush University Rush University Richard Hug 5-13-08 Associate Professor Public and Environmental Affairs Indiana University Northwest Ill ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: Parent's Experience Raising a Child with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Charlotte Strahm, Doctor of Nursing Science, 2008 Dissertation directed by: Deborah Gross, Professor College of Nursing Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a common neurobiological disorder affecting 3%-l 1% of children leading to 30% -50% of child referrals for mental health services. Symptoms include diminished attention span, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, behaviors that can negatively affect family relationships and functioning. The purpose of this study is to describe aspects of perceived family quality among those with and without a child diagnosed with ADHD. The convenience sample consisted of 11 families of 6-12 year old children with ADHD and 12 families of children with no known physical or emotional disabilities. -

European Journal of Educational Sciences (EJES)

European Journal of Educational Sciences, EJES June 2018 edition Vol.5, No.2 ISSN 1857- 6036 European Journal of Educational Sciences (EJES) 2018 / June Publisher: European Scientific Institute, ESI Reviewed by the ”European Journal of Educational Sciences” editorial board 2018 June 2018 edition vol. 5, no. 2 The contents of this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of the European Scientific Institute. Neither the European Scientific Institute nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use which may be made of the information in this publication. ISSN 1857- 6036 European Journal of Educational Sciences, EJES June 2018 edition Vol.5 No.2 ISSN 1857- 6036 About The Journal The European Journal of Educational Sciences is a peer - reviewed international journal which accepts high quality research articles. It is a quarterly journal published at the end of March, June, September and December and is available to all researchers who are interested in publishing their scientific achievements. We welcome submissions focusing on theories, methods and applications in educational sciences, both articles and book reviews. Authors can publish their articles after a review by our editorial board. Our mission is to provide greater and faster flow of the newest scientific thought. EJES’s role is to be a kind of a bridge between the researchers around the world. “EJES” is opened to any researchers, regardless of their geographical origin, race, nationality, religion or gender as long as they have an adequate scientific paper in the educational sciences field. EJES provides immediate open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public, supports a greater global exchange of knowledge. -

The Relationship Between Husband Supportiveness and Wife's Adjustment to Motherhood

The Relationship Between Husband Supportiveness and Wife's Adjustment to Motherhood Edith Catlin Lawrence Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., Hollins College, 1972 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Education University of Virginia May, 1982 FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA The Relationship Between Husband Supportiveness and Wife's Adjustment to Motherhood Edith Catlin Lawrence Approved: \ Richard R. Abidin, Ed.D., Chairman Donna Cowan; Ph.D. Herbert Richards, Ph.D. David B. Waters, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •••• C) • • • • 0 • • i LIST OF FIGURES ••.••••••••••• iii LIST OF TABLES. • • • • • • • • • • iv ABSTRACT o • • • • Iii • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • vi CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION. • . 1 Statement of the Problem •. 6 II LITERATURE REVIEW. 8 Research on Parenthood as "Crisis" . • • • . 9 Areas of Concern for New Mothers • • • • 17 The Effect of Sex Role Ideology on the Husband's Role. • • • • • • • • • 21 Support and Resistance to Stress • • • • • • 24 Specific Aspects of Husband Supportiveness . 34 Summary. • . • . 48 III METHODOLOGY. 51 Subjects. • . • • • • • . • . • . • • • 51 Procedure. • • • • • • . • • • • • • . • . 53 Instruments. • . • • . • • • • • • • • 5 6 Factor Analysis of Husband Support Measure • 65 IV RESULTS • . 78 Sample Characteristics •••• 78 Data Analysis ••.•.•••• 82 V DISCUSSION •.••• . 104 Husband Support. • • • • • • • • • . • • • • 104 Husband Support and Stress Subscales • • • • 113 Sex Role Ideology. • • • • • • • • • • 115 Clinical Implications and Suggestions for Future Research. • • . • • 116 REFERENCES. • . • . • • . • • • . • • • • • 152 APPENDIX A Summary of Descriptive Statistics of Demo- graphic Variables for Sample of 100 Couples. • 120 B Letter to Parents About Nature of Study •• • 121 C Parenting Stress Index •• . • 12 3 D Husband Support Scale. 135 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the members of my committee, Dr. -

Life After an Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: a Comparison of Stress and Coping Profiles of African American and Caucasian Caregivers

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Psychology Theses & Dissertations Psychology Summer 2016 Life After an Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: A Comparison of Stress and Coping Profiles of African American and Caucasian Caregivers Takeshia Williams Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/psychology_etds Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Takeshia. "Life After an Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: A Comparison of Stress and Coping Profiles of African American and Caucasian Caregivers" (2016). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Dissertation, Psychology, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/5hr0-1p83 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/psychology_etds/39 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFE AFTER AN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER DIAGNOSIS: A COMPARISON OF STRESS AND COPING PROFILES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN AND CAUCASIAN CAREGIVERS by Takeshia Williams B.A. May 2009, Albion College M.A. July 2014, Norfolk State University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculties of Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk State University, and Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY VIRGINIA CONSORTIUM PROGRAM IN CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY August 2016 Approved by: Kathrin Hartmann (Director) Eastern Virginia Medical School Scott Debb (Member) Norfolk State University Serina Neumann (Member) Eastern Virginia Medical School James Paulson (Member) Old Dominion University Maria Urbano (Member) Eastern Virginia Medical School ABSTRACT LIFE AFTER AN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER DIAGNOSIS: A COMPARISON OF STRESS AND COPING PROFILES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN AND CAUCASIAN CAREGIVERS Takeshia V. -

Graduates and Degree Candidates

Graduates and Degree Candidates Julie Diane Elizabeth Jackson-Murphy ............... Christine Marie Stoehr Shugart ........................... School of Medicine Fairfax VA Charlottesville VA Conferred August 19, 2004 Sonia Jain ........................................Bluefield VA Mark Matthew Sieminski ..........West Seneca NY Elizabeth Bradley Johnson ........... Mayesville SC Breton Scot Stetka .............................Stafford VA Doctor of Medicine Katherine Yu-Chieh Jou .........Charlottesville VA Ryan William Stidham ...................... Newark DE John Kanu ..........................................Clifton VA Tad Kim ..........................................Riverdale NY Catherine Marie Straub ..........Charlottesville VA Tae-Wu Edward Kim ........................Cerritos CA Shannon Danielle Sullivan .................................. Conferred January 5, 2005 John Brian Klein .............................Arlington VA Charlottesville VA Doctors of Medicine Andrew Lee-Wah Koo ............Charlottesville VA Julie Ann Suppa ......................Charlottesville VA Matthew David Cole ........ Huntington Beach CA Girish Andaneppa Kori ................Springfield VA Paul Andrew Sykes .................Charlottesville VA Meenakshi Swaminathan Kumar ........................ Caleb Edward Kroll ............... Christiansburg VA Samuel Andrew Taylor, Jr. ............... Madison VA Greenville NC John Francis Kugler .....................Alexandria VA Jared McKean Theler ...........................Sandy UT Andrew Frederic Kuntz ..........Charlottesville -

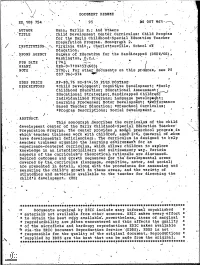

Materials- Available to the Teacher for Directing the * to Obtain the Best Copy Available%

DOCUMENT RESUME 4 ED,, 108 754 . 95 AS 007 961 AUTHOR Mann, Marlis E.; And 'Others 1. 'TITLE , Child Development Center Cdrridulum: ChildProgZam for the Early Childhood-Spedial Education Teacher , pteparati-oh- Program. Monograph 2. , / INSTITUTIO'N. -N Virginia Univ., Charlottesville:. Sdhool of . Education. a SPOWS ,AGENCY Bu4eau of Education_ for the Handicapped (DHE61/0E) , Washington, I.I.C..1,,. 1 % .. PUB phTE I 743, --.....-, , GRANT, ", . OEG-0-710415`(603). , NOTE- ..27913.; For other dO-ddments on this pr graM, see PS liP" , % 0 007 ,960-974 EDRS PRICE .Mis.,-$0..76 HC-$14:59ft-b,S, 'POSTAGE' DESCRIPTORS *Child Development; Cognit;ive Development; *Early .. Childhood Education=; Eddcationii Assessment;. Educational Strategie-s;:, Handicapped Childr Inditidualiked Programs; Language Deveiopt nt; Learning prodesses; Motor =Development; iforMance. ' Based Teacher Education; *Preschool Curridulum; *Program Descriptions; Social Development 4 , .=ABSTRACT. This monograph ..describes the curriculum of the child- development- center of the- :Early -Childhood.--Special Education- =Teacher' Preparation_ -Program. Th-center provides- -mod41_ preschool prOgrah-.in which "-teacher trainees Work ',with_ child-red, ag0,2,16_; (several of whom, have developmental deficiendiesin. The- Curriculum- is :designed to he;p- -teacher traineeS--organize the learning =eriiironnien't for an experience-dentered curriculumWhieh -allows_ children to- explore 'knowledge in an interdisciplinary ,and.-_ -murtiSensory Way._ Variois. -aspects- of the curridUIdils_ theoretidal, rationale are -:discussed -. -DeSired -outcomeS and growth =seqUendes for the d-evelopmental areas covered- by -the_ curriculum lIangkiage, -dognitive-,_ motor_,_ and -social) assessing_ =and. are presented= in detail,. along W-ith- the- -prOcedures- -for measuring- the-child-1s- growth -in these =areas, and the =Variety -of- stratelies and.-, materials- _available to the teacher for directing the chi:1-'31s_ development.- -(1b): tl - .