Filial Therapy with Adolescent Parents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME UD 032 911 Thinking About & Accessing Policy Related to Addressing Barriers to Learning. Technical Assistanc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 430 068 UD 032 911 TITLE Thinking about & Accessing Policy Related to Addressing Barriers to Learning. Technical Assistance Sampler. INSTITUTION California Univ., Los Angeles. Center for Mental Health in Schools. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Washington, DC. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. PUB DATE 1998-02-23 NOTE 47p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Change; *Educational Policy; Educational Practices; *Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *Learning; Program Development; Program Implementation IDENTIFIERS *Reform Efforts ABSTRACT This "sampler" package has been developed to provide immediate information on resources related to educational policy related to addressing barriers to learning. The first section lists 69 resources for information about educational improvement and learning, including ERIC. The second section lists 14 print resources for facts relevant to showing policy need. Section 3 lists guides and model programs, including some state initiatives relevant to addressing barriers to learning. Section 4 lists agencies and resource centers that focus on policy concerns or offer resources for the study and formulation of policy. Section 5 lists Web sites related to educational policy, and the sixth section describes the three major resources from the Center: documents from the Clearinghouse, the consultation cadre, and center staff. -

The Use of Play Therapy with Adult Survivors of Childhood Abuse

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2007 The Use of Play Therapy with Adult Survivors of Childhood Abuse Mary J. Roehrig Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons, and the Other Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Roehrig, Mary J., "The Use of Play Therapy with Adult Survivors of Childhood Abuse" (2007). Dissertations. 666. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/666 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University School of Education THE USE OF PLAY THERAPY WITH ADULT SURVIVORS OF CHILDHOOD ABUSE A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Mary J. Roehrig April 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3261213 Copyright 2007 by Roehrig, Mary J. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

1Ylr!Jijdtal Molly Welch Deal

Play Therapy Issues and Applications Pertaining Deaf Children: Analysis and Recommendations by Justin Matthew Small A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree III Guidance & Counseling Approved: 2 Semester Credits 1Ylr!jiJDtal Molly Welch Deal The Graduate School University of Wisconsin-Stout July, 2009 ii The Graduate School University of Wisconsin-Stout Menomonie, WI Author: Small, Justin M. Title: Play Therapy Issues and Applications Pertaining Deaf Children: Analysis and Recommendations Graduate Degree! Major: MS Guidance & Counseling Research Adviser: Molly Welch Deal MonthfYear: July, 2009 Number of Pages: 48 Style Manual Used: American Psychological Association, 5th edition ABSTRACT Play is crucial toward understanding the child since his natural instinct is to play. Though studies have been conducted by various counselors and therapists on the application of their theories and techniques of play therapy, there are limited studies in the effectiveness of play therapy with deaf individuals. The lack of direct communication and the low number of students who are deaf and hard of hearing within the school systems contribute to the high incidences of emotional difficulties among students. The purpose of this study is to fill a gap in research and establish effective play techniques to use with deaf children. This study also aims at critically analyzing the current research to provide recommendations for play therapists, the use of play therapy, and implications for future research. iii The Graduate School University of Wisconsin Stout Menomonie, WI Acknowledgments Kristin this is for you. For all the times I came home and needed to work on this paper to get it completed and you allowed me to do just that. -

The Benefits of Child-Centered Play Therapy and Filial Therapy for Pre-School-Aged Children with Reactive Attachment Disorder and Their Famiies

Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2014 The benefits of child-centered play therapy and filial therapy for pre-school-aged children with reactive attachment disorder and their famiies Andrea S. White Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation White, Andrea S., "The benefits of child-centered play therapy and filial therapy for pre-school-aged children with reactive attachment disorder and their famiies" (2014). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/846 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrea White The Benefits of Child-Centered Play Therapy and Filial Therapy for Preschool-Aged Children with Reactive Attachment Disorder and Their Families ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to investigate, from a theoretical perspective, the best treatment approach for preschool-aged children with Reactive Attachment Disorder. The challenges and needs of these children can be extensive, and the search for effective treatment is ongoing. Two specific questions of focus were: How are the theories behind Non-Directive Play Therapy/Child-Centered Play Therapy and Filial Therapy useful in conceptualizing the experience of therapy for a child with attachment disorder? And, how could these treatments be used to benefit children with attachment disorders and their families? The research for this paper involved a literature review of peer-reviewed articles on Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) and treatment, original sources describing Attachment Theory, Non-Directive Play Therapy and Filial Therapy, and the DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10. -

Filial Therapy with Teachers of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Preschool

FILIAL THERAPY WITH TEA CHERS OF DEAF AND HARD OF HEARING PRESCHOOL CHILDREN David Michael Smith, B.A., M.Div. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2002 APPROVED: Garry Landreth, Major Professor Kenneth Sewell, Minor Professor Sue Bratton, Committee Member Janice Holden, Program Coordinator Michael Altedruse, Chair of the Department of Counseling, Development, and Higher Education C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Smith, David Michael, Filial Therapy with Teachers of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Preschool Children, Doctor of Philosophy (Counseling, Development, and Higher Education), May 2002, 189 pages, 28 tables, 259 references, 39 titles. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of Filial Therapy training in increasing teachers of deaf and hard of hearing preschool students’: 1) empathic responsiveness with their students; 2) communication of acceptance to their students; 3) allowance of self- direction by their students. A second purpose was to determine the effectiveness of Filial Therapy training in reducing experimental group students’: 1) overall behavior problems; 2) internalizing behaviors; and 3) externalizing behavior problems. Filial Therapy is a didactic/dynamic modality used by play therapists to train parents and teachers to be therapeutic agents with their children and students. Teachers are taught primary child-centered play therapy skills for use with their own students in weekly play sessions with their students. Teachers learn to create a special environment that enhances and strengthens the teacher-student emotional bond by means of which both teacher and child are assisted in personal growth and change. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9316162 The relation of children’s everyday stressors to parental stress Gustafson, Yvonne Elaine, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1993 UMI 300 N. -

PROGRAMS and SERVICES Hi Mark

PROGRAMS and SERVICES Hi Mark, I need a yard sign with the following information…please see attached for sample of emotions under the description….let me kmowif this doesn’t make sense. Feeling…. Anxious Sad Overwhelmed LOGO SummitCounseling.org 678-893-5300 Thanks! Cathy FREE, Anonymous, Online Screenings http://summitcounseling.org/screening An anonymous online screening for: PROGRAMS and SERVICES Life at the Summit Whatever your background or age/stage of life might be, we are here to walk with you through life’s journey. We foster a safe, confidential environment in which lives are reclaimed, relationships are restored and hope is renewed. Kids & Teens at the Summit ADHD Screening (Brief) Offered at a fraction of the cost of comprehensive psychoeducational testing. Based on the screening results, our psychologist makes recommendations to parents regarding the possible need for: additional psychoeducational testing, counseling, tutoring, behavioral modifications, and/or other therapy. 678-893-5300 | SummitCounseling.org 1 Testing & Assessments (Comprehensive) Parents of children who are struggling academically often need help understanding why their children are having difficulty in school, and what to do about it. Comprehensive psychoeducational evaluations for children, adolescents, and young adults are available. Play (& Recreational) Therapy This therapy builds on a natural approach, where children and teens learn about themselves and the relationships around them. Through play therapy (younger children) and recreational activities (older children & teens), young people communicate more freely, express feelings, modify behavior, develop problem-solving skills, and learn a variety of healthy ways to relate to others. Parent Coaching (Filial Therapy) This popular, evidenced-based parent training program equips parents to incorporate many of the same skills used by play therapists to help their children experience healing and growth. -

Basics and Beyond

SECOND EDITION play therapy basics and beyond Terry Kottman AMERICAN COUNSELING ASSOCIATION 5999 Stevenson Avenue Alexandria, VA 22304 www.counseling.org SECOND EDITION play therapy basics and beyond Copyright © 2011 by the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 AMERICAN COUNSELING ASSOCIATION 5999 Stevenson Avenue Alexandria, VA 22304 DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS Carolyn C. Baker PRODUCTION MANAGER Bonny E. Gaston EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Catherine A. Brumley COPY EDITOR Elaine Dunn Cover and text design by Bonny E. Gaston LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Kottman, Terry. Play therapy : basics and beyond/Terry Kottman.—2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-55620-305-3 (alk. paper) 1. Play therapy. 2. Psychotherapy. I. Title. RJ505.P6K643 2011 616.89’1653—dc22 2010027176 play dedication For Jacob, who teaches me what being a kid (and now, a teen) is all about—every day—whether I want to learn or not. • • • For Rick, who is there with me learning—there for the good, the bad, and the ugly. iii table of contents Acknowledgments xi Preface xiii About the Author xvii PART 1 basic concepts Chapter 1 Introduction to Play Therapy 3 Therapeutic Powers of Play 4 Personal Qualities -

ABSTRACT AHERN, LISA SENATORE. Psychometric

ABSTRACT AHERN, LISA SENATORE. Psychometric Properties of the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form. (Under the direction of Mary Haskett.) Psychometric properties of the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form were investigated using a heterogeneous sample of 185 mothers and fathers of children between the ages of 4- 10 years. The Difficult Child and Parent Distress subscales, as well as Total PSI-SF, were found to be internally consistent. Confirmatory factor analysis did not reveal support for a three-factor model. Results were mixed in terms of support for convergent and discriminant validity. The PSI-SF Total and subscales were related to measures of parent psychopathology and perceptions of child adjustment, but not to observed parent and child behavior. Implications of these findings and suggestions for future research are discussed. PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES OF THE PARENTING STRESS INDEX – SHORT FORM by LISA SENATORE AHERN A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Raleigh 2004 APPROVED BY: ________________________________ Chair of Advisory Committee _______________________________ _______________________________ Psychometric ii DEDICATION To my parents, Mary Grace and John Senatore, who always taught me that I could be anything I wanted to be and do anything I set my mind to, and to my husband, David, whose love and support made this paper possible. Psychometric iii BIOGRAPHY Lisa Ann Senatore Ahern was born November 4, 1978 in Edison, NJ. She is the daughter of John and Mary Grace Senatore and the sister of Michael Senatore. -

Workshops Attended: Cultural Consciousness in Clinical Practice: Working with Adults

Workshops attended: Cultural Consciousness in Clinical Practice: Working With Adults. Presented by Kate Amatruda, LMFT, Online, October, 2014. Ethics and Law for Psychologists Using the DSM-IV-TR Legally and Ethically: Best Practices. Presented by Pamela Harmell, Ph.D., Online, October, 2014. Domestic Violence: Spousal and Partner Abuse. Presented by Kate Amatruda, LMFT, Online, October, 2014. HIPAA Updates. Presented by Vista Continuing Education, Online, October, 2013. Law and Ethics For Psychologists. Revolutionizing Diagnosis and Treatment Using the DSM-5. Presented by Robert Bogenberger, Ph.D., Fort Worth, TX, 4-24-13. Ethics in Mental Health Practice. Presented by Federic G Reamer, Ph.D., Online, 10-18-12. Sensory Processing and ASD: Making Sense-ory Out of Autism. Presented by Tara Delaney, MS, OTR/L, October 16, 2012. Bipolar Disorder: Evidence Based Practice. Presented by William A. Cook, Ph.D., Online, 10-23-11. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Presented by William A. Cook, Ph.D., Online, 10-22-11. Anxiety Disorders. Presented by William A. Cook, Ph.D., Online, 10-22-11. Boundaries in Mental Health Treatment. Presented by William A. Cook, Ph.D., Online, 10-22-11. Mandatory Abuse Reporting. Presented by William A. Cook, Ph.D., Online, 10-22-11. Certification as a Person Trainer. Exam taken/passed, 10-04-11 HKC Kettlebell Certification Course. Presented by Franz Snideman, RKC and Michael French, RKC, Oceanside, CA, 9-03-11. Obesity. Presented by Vista Continuing Educ., Online, 10-11-10. The Developing Brain and Child Abuse. Presented by Vista Continuing Educ., Online, 10-10-10. Anxiety and Panic Disorder. Presented by Vista Continuing Educ., Online, 10-11-10. -

Independent Evidence Review of Post-Adoption Support Interventions

Independent evidence review of post-adoption support interventions Research report June 2016 Laura Stock, Dr Thomas Spielhofer and Matthew Gieve – The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations (TIHR) Contents Acknowledgments 5 Executive summary 6 Overview 6 Background 6 Methodology 7 Key findings 9 Extent of evidence: general overview 9 Play Therapies 9 Therapeutic Parenting Training 10 Conduct problem therapies 10 Cognitive and behavioural therapies 11 Overarching categories 11 Recommended steps to build the evidence base 11 1. Background, Aims and Approach 13 1.1 Needs of Adoptive Children 13 1.2 Aims of the Evidence Review 14 2. Theories of Therapeutic Support for Adoptive Families 18 2.1 Theories and Types of Therapy 18 2.2 Grouping the Interventions 20 3. Findings on the Interventions 22 3.1 Play Therapies 23 3.1.1 Theraplay 23 3.1.2 Filial Therapy 27 3.1.3 SafeBase 29 3.2 Therapeutic Parenting Training 31 3.2.1 Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy 31 3.2.2 Nurturing Attachments 34 3.2.3 AdOpt 36 3.3 Conduct Problem therapies 38 2 3.3.1 Non Violent Resistance (NVR) 38 3.3.2 Break4Change 41 3.3.3 Multisystemic Therapy (MST) 42 3.4 Cognitive and Behavioural therapies 43 3.4.1 Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing Therapy (EMDR) 44 3.4.2 Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) 45 3.5 Overarching Categories 48 3.5.1 Psychotherapy 48 3.5.2 Equine Therapy 51 3.5.3 Creative Therapies 52 4. Building the Evidence Base 55 4.1 Further Evidence Review 55 4.2 Other research 58 APPENDIX 60 Appendix A: Bibliography 60 Appendix B: Methodology 81 Appendix C: List of Additional Interventions 92 3 Tables Table 1 Research questions ........................................................................................... -

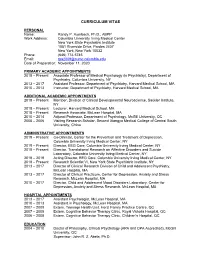

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE PERSONAL Name: Randy P. Auerbach, Ph.D., ABPP Work Address: Columbia University Irving Medical Center New York State Psychiatric Institute 1051 Riverside Drive, Pardes 2407 New York, New York 10032 Phone: (646) 774-5745 Email: [email protected] Date of Preparation: November 11, 2020 PRIMARY ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2018 – Present Associate Professor of Medical Psychology (in Psychiatry), Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, NY 2013 – 2017 Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, MA 2010 – 2013 Instructor, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, MA ADDITIONAL ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2018 – Present Member, Division of Clinical Developmental Neuroscience, Sackler Institute, NY 2018 – Present Lecturer, Harvard Medical School, MA 2018 – Present Research Associate, McLean Hospital, MA 2010 – 2014 Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychology, McGill University, QC 2005 – 2006 Visiting Research Scholar, Second Xiangya Medical College of Central South University, China ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS 2019 – Present Co-Director, Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2019 – Present Director, EEG Core, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2018 – Present Director, Translational Research on Affective Disorders and Suicide Laboratory, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2018 – 2019 Acting Director, EEG Core, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NY 2018 – Present Research Scientist VI, New York State