August 2017, Vol. 43 No. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

155891 WPO 43.2 Inside WSUP C.Indd

MAY 2017 VOL 43 NO 2 LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION • Black Sands and White Earth • Baleen, Blubber & Train Oil from Sacagawea’s “monstrous fish” • Reviews, News, and more the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal VOLUME 11 - 2017 The Henry & Ashley Fur Company Keelboat Enterprize by Clay J. Landry and Jim Hardee Navigation of the dangerous and unpredictable Missouri River claimed many lives and thousands of dollars in trade goods in the early 1800s, including the HAC’s Enterprize. Two well-known fur trade historians detail the keelboat’s misfortune, Ashley’s resourceful response, and a possible location of the wreck. More than Just a Rock: the Manufacture of Gunflints by Michael P. Schaubs For centuries, trappers and traders relied on dependable gunflints for defense, hunting, and commerce. This article describes the qualities of a superior gunflint and chronicles the evolution of a stone-age craft into an important industry. The Hudson’s Bay Company and the “Youtah” Country, 1825-41 by Dale Topham The vast reach of the Hudson’s Bay Company extended to the Ute Indian territory in the latter years of the Rocky Mountain rendezvous period, as pressure increased from The award-winning, peer-reviewed American trappers crossing the Continental Divide. Journal continues to bring fresh Traps: the Common Denominator perspectives by encouraging by James A. Hanson, PhD. research and debate about the The portable steel trap, an exponential improvement over snares, spears, nets, and earlier steel traps, revolutionized Rocky Mountain fur trade era. trapping in North America. Eminent scholar James A. Hanson tracks the evolution of the technology and its $25 each plus postage deployment by Euro-Americans and Indians. -

FINAL CASE STUDY REPORT to the 60TH LEGISLATURE WATER POLICY INTERIM COMMITTEE (With Public Comments) by the Montana Bureau of M

FINAL CASE STUDY REPORT TO THE 60TH LEGISLATURE WATER POLICY INTERIM COMMITTEE (with public comments) by the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology September 11, 2008 WPIC members: Senator Jim Elliott, Chair Senator Gary L Perry, vice Chair Representative Scott Boggio Representative Jill Cohenour Representative Bill McChesney Representative Walter McNutt Senator Larry Jent Senator Terry Murphy HB 831 Report CONTENTS Recommendations to the Water Policy Interim Committee ..............................................1 SECTION 1: General Concepts of Stream–Aquifer Interaction and Introduction to the Closed Basin Area .......................................................................................................3 Introduction ...............................................................................................................5 Th e Hydrologic Cycle ............................................................................................5 Occurrence of Ground Water .................................................................................5 Stream–Aquifer Interaction ...................................................................................7 Closed Basin Regional Summary ...............................................................................10 Geology ....................................................................................................................18 Distribution of Aquifers ............................................................................................19 Ground-Water -

Level I History.Indd

Crow Tipi Village A. Wolf Activity 2 History - The Power of a Story Trails Through the Years By Christy Fleming The Bad Pass Trail, marked by rock cairns, was still not an easy trip. It was a well known weaves its way along the rugged western edge fact by those that drove along the trail, that they of Bighorn Canyon, from the mouth of the Sho- should always carry a tire repair kit with them as shone River to the mouth of Grapevine Creek. they were almost guaranteed at least one fl at tire One may guess from its name that the Bad Pass along the way. trail was not an easy trail. It was better than the alternatives of crossing the mountains or the Today the park road follows closely the original dangers of possibly drowning in the untamed path of the Bad Pass, some times following over waters of the Bighorn River coursing through the the top of it. If this trail could talk it would have canyon. The Crow told stories of evil spirits that years of stories to share. The stories of adventure resided in the canyon, serving as an additional have now turned to stories of wildlife viewing deterrent to river travel. and recreation. As the years go by more stories will be added and others will study them. Who Native people walked and camped along this knows, maybe someday in the future, students trail for 10,000 to 12,000 years while traveling will be studying our impact on the Bad Pass Trail. to the buff alo plains. -

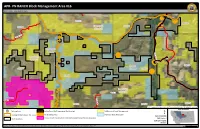

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page

APR- PN RANCH Block Management Area #16 BMA Rules - See Reverse Page Ch ip C re e k 23N15E 23N17E 23N16E !j 23N14E Deer & Elk HD # 690 Rd ille cev Gra k Flat Cree Missouri River k Chouteau e e r C County P g n o D B r i d g e Deer & Elk R d HD # 471 UV236 !j Fergus 22N17E 22N14E County 22N16E 22N15E A Deer & Elk r ro w The Peak C HD # 426 r e e k E v Judi e th r Riv s e ge Rd r Ran o n R d 21N17E 21N15E 21N16E U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Services Agency Aerial Photography Field Office Area of Interest !j Parking Area Safety Zone (No Trespassing, No Hunting) US Bureau of Land Management º 1 6 Hunting Districts (Deer, Elk, Lion) No Shooting Area Montana State Trust Land 4 Date: 5/22/2020 2 Moline Ranch Conservation Easement (Seperate Permission Required) FWP Region 4 7 BMA Boundary 5 BLM 100K Map(s): 3 Winifred Possession of this map does not constitute legal access to private land enrolled in the BMA Program. This map may not depict current property ownership outside the BMA. It is every hunter's responsibility to know the 0 0.5 1 land ownership of the area he or she intends to hunt, the hunting regulations, and any land use restrictions that may apply. Check the FWP Hunt Planner for updates: http://fwp.mt.gov/gis/maps/huntPlanner/ Miles AMERICAN PRAIRIE RESERVE– PN RANCH BMA # 16 Deer/Elk Hunting District: 426/471 Antelope Hunting District: 480/471 Hunting Access Dates: September 1 - January 1 GENERAL INFORMATION HOW TO GET THERE BMA Type Acres County Ownership » North on US-191 15.0 mi 2 20,203 Fergus Private » North on Winifred Highway 24.0 mi » West on Main St. -

Montana State Parks Guide Reservations for Camping and Other Accommodations: Toll Free: 1-855-922-6768 Stateparks.Mt.Gov

For more information about Montana State Parks: 406-444-3750 TDD: 406-444-1200 website: stateparks.mt.gov P.O. Box 200701 • Helena, MT 59620-0701 Montana State Parks Guide Reservations for camping and other accommodations: Toll Free: 1-855-922-6768 stateparks.mt.gov For general travel information: 1-800-VISIT-MT (1-800-847-4868) www.visitmt.com Join us on Twitter, Facebook & Instagram If you need emergency assistance, call 911. To report vandalism or other park violations, call 1-800-TIP-MONT (1-800-847-6668). Your call can be anonymous. You may be eligible for a reward. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks strives to ensure its programs, sites and facilities are accessible to all people, including those with disabilities. To learn more, or to request accommodations, call 406-444-3750. Cover photo by Jason Savage Photography Lewis and Clark portrait reproductions courtesy of Independence National Historic Park Library, Philadelphia, PA. This document was produced by Montana Fish Wildlife & Parks and was printed at state expense. Information on the cost of this publication can be obtained by contacting Montana State Parks. Printed on Recycled Paper © 2018 Montana State Parks MSP Brochure Cover 15.indd 1 7/13/2018 9:40:43 AM 1 Whitefish Lake 6 15 24 33 First Peoples Buffalo Jump* 42 Tongue River Reservoir Logan BeTableaverta ilof Hill Contents Lewis & Clark Caverns Les Mason* 7 16 25 34 43 Thompson Falls Fort3-9 Owen*Historical Sites 28. VisitorMadison Centers, Buff Camping,alo Ju mp* Giant Springs* Medicine Rocks Whitefish Lake 8 Fish Creek 17 Granite11-15 *Nature Parks 26DisabledMissouri Access Headw ibility aters 35 Ackley Lake 44 Pirogue Island* WATERTON-GLACIER INTERNATIONAL 2 Lone Pine* PEACE PARK9 Council Grove* 18 Lost Creek 27 Elkhorn* 36 Greycliff Prairie Dog Town* 45 Makoshika Y a WHITEFISH < 16-23 Water-based Recreation 29. -

2012 Montana Nonpoint Source Management Plan – Table of Contents

Montana Nonpoint Source Management Plan 2012 Brian Schweitzer, Governor Richard Opper, Director DEQ WQPBWPSTR-005 Prepared by: Water Quality Planning Bureau Watershed Protection Section Acknowledgements: The Watershed Protection Section would like to thank all of our partners and collaborators for their input and advice for this update to the Montana Nonpoint Source Management Plan. Montana Department of Environmental Quality Water Quality Planning Bureau 1520 E. Sixth Avenue P.O. Box 200901 Helena, MT 59620-0901 Suggested citation: Watershed Protection Section. 2012. Montana Nonpoint Source Management Plan. Helena, MT: Montana Dept. of Environmental Quality. 2012 Montana Nonpoint Source Management Plan – Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... v Nonpoint Source Management Plan Overview ............................................................................................ 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.0 Montana’s NPS Pollution Management Program Framework ............................................................ 1-1 1.1 Water Quality Standards and Classification ..................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Impaired Waterbodies and 303(d) List and Water Quality Assessment ......................................... -

Montana State Parks Senate Bill 3, State Agency Biennial Report, 2010-2011

Montana State Parks Senate Bill 3, State Agency Biennial Report, 2010-2011 STATE PARKS Report Prepared by: Sara Scott State Parks Heritage Resources Program January 2012 Acknowledgments Information for this report was graciously provided by regional and park management staff who combed through numerous files and documents to obtain information on project costs and stewardship efforts. Many thanks go to the following individuals for their help: Lee Bastian, Jerry Walker, Matt Marcinek, Doug Habermann, John Little, Loren Flynn, Craig Marr, Dale Carlson, Richard Hopkins, Colin Maas, Darla Bruner, Ryan Sokoloski, and Bob Peterson. Roger Semler compiled information on administrative costs and helped oversee the SB3 reporting process. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................... Introduction................................................................................................................................................ 1 State Park Heritage Resources............................................................................................................... 1 Property Status and Condition................................................................................................................ 4 Heritage Site Stewardship Efforts........................................................................................................... 6 Site Enhancement/Maintenance Needs............................................................................................... -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL COPYRIGHTED I

Avalanche Campground (MT), 66 Big Horn Equestrian Center (WY), Index Avenue of the Sculptures (Billings, 368 MT), 236 Bighorn Mountain Loop (WY), 345 Bighorn Mountains Trail System INDEX A (WY), 368–369 AARP, 421 B Bighorn National Forest (WY), 367 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Backcountry camping, Glacier Big Red (Clearmont, WY), 370 (MT), 225–227 National Park (MT), 68 Big Red Gallery (Clearmont, WY), Academic trips, 44–45 Backcountry permits 370 Accommodations, 413–414 Glacier National Park (MT), Big Salmon Lake (MT), 113 best, 8–10 54–56 Big Sheep Creek Canyon (MT), 160 for families with children, 416 Grand Teton (WY), 325 Big Sky (MT), 8, 215–220 Active vacations, 43–52 Yellowstone National Park Big Sky Brewing Company AdventureBus, 45, 269 (MT—WY), 264 (Missoula, MT), 93 Adventure Sports (WY), 309, 334 Backcountry Reservations, 56 Big Sky Candy (Hamilton, MT), 96 Adventure trips, 45–46 Backcountry skiing, 48 Big Sky Golf Course (MT), 217 AdventureWomen, 201–202 Backroads, 45, 46 Big Sky Resort (MT), 216–217 Aerial Fire Depot and Baggs (WY), 390 Big Sky Waterpark (MT), 131 Smokejumper Center (Missoula, Ballooning, Teton Valley (WY), Big Spring (MT), 188 MT), 86–87 306 Big Spring Creek (MT), 187 Air tours Bannack (MT), 167, 171–172 Big Timber Canyon Trail (MT), 222 Glacier National Park (MT), 59 Bannack Days (MT), 172 Biking and mountain biking, 48 the Tetons (WY), 306 Barry’s Landing (WY), 243 Montana Air travel, 409, 410 Bay Books & Prints (Bigfork, MT), Big Sky, 216 Albright Visitor Center 105 Bozeman, 202 (Yellowstone), 263, 275 -

Montana Fishing Regulations

MONTANA FISHING REGULATIONS 20March 1, 2018 — F1ebruary 828, 2019 Fly fishing the Missouri River. Photo by Jason Savage For details on how to use these regulations, see page 2 fwp.mt.gov/fishing With your help, we can reduce poaching. MAKE THE CALL: 1-800-TIP-MONT FISH IDENTIFICATION KEY If you don’t know, let it go! CUTTHROAT TROUT are frequently mistaken for Rainbow Trout (see pictures below): 1. Turn the fish over and look under the jaw. Does it have a red or orange stripe? If yes—the fish is a Cutthroat Trout. Carefully release all Cutthroat Trout that cannot be legally harvested (see page 10, releasing fish). BULL TROUT are frequently mistaken for Brook Trout, Lake Trout or Brown Trout (see below): 1. Look for white edges on the front of the lower fins. If yes—it may be a Bull Trout. 2. Check the shape of the tail. Bull Trout have only a slightly forked tail compared to the lake trout’s deeply forked tail. 3. Is the dorsal (top) fin a clear olive color with no black spots or dark wavy lines? If yes—the fish is a Bull Trout. Carefully release Bull Trout (see page 10, releasing fish). MONTANA LAW REQUIRES: n All Bull Trout must be released immediately in Montana unless authorized. See Western District regulations. n Cutthroat Trout must be released immediately in many Montana waters. Check the district standard regulations and exceptions to know where you can harvest Cutthroat Trout. NATIVE FISH Westslope Cutthroat Trout Species of Concern small irregularly shaped black spots, sparse on belly Average Size: 6”–12” cutthroat slash— spots -

NPS Management Policies

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Fire Management Plan Requirement ...................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Collaborative Planning Process .............................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Federal Policy Implementation ............................................................................................................... 3 1.4 NEPA/NHPA Planning Requirements ................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Fire Management Plan Authorities ......................................................................................................... 3 2 RELATIONSHIP TO LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING AND FIRE POLICY ...................................... 5 2.1 NPS Management Policies ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Enabling Legislation and Purpose of NPS Unit ..................................................................................... 5 2.3 General Management Plan ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.4 Resource Management Plan .................................................................................................................. -

Trails and Aboriginal Land Use in the Northern Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1992 Trails and Aboriginal land use in the northern Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming Steve Platt The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Platt, Steve, "Trails and Aboriginal land use in the northern Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming" (1992). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3933. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3933 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial giain may be undertaken only with the author's written consent. MontanaUniversity of TRAILS AND ABORIGINAL LAND USE IN THE NORTHERN BIGHORN MOUNTAINS, WYOMING By Steve Piatt B.A. University of Vermont, 1987 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 19-92 Approved by 4— Chair, Board of Examiners Death, Graduate £>c3Tooi 7 is. rtqz Date UMI Number: EP36285 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

SHPO Preservation Plan 2016-2026 Size

HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Front cover images (left to right, top to bottom): Doll House, F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Cheyenne. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Downtown Buffalo. Photograph by Richard Collier Moulton barn on Mormon Row, Grand Teton National Park. Photograph by Richard Collier. Aladdin General Store. Photograph by Richard Collier. Wyoming State Capitol Building. Photograph by Richard Collier. Crooked Creek Stone Circle Site. Photograph by Danny Walker. Ezra Meeker marker on the Oregon Trail. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Green River Drift. Photograph by Jonita Sommers. Legend Rock Petroglyph Site. Photograph by Richard Collier. Ames Monument. Photograph by Richard Collier. Back cover images (left to right): Saint Stephen’s Mission Church. Photograph by Richard Collier. South Pass City. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Wyoming Theatre, Torrington. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Plan produced in house by sta at low cost. HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Matthew H. Mead, Governor Director, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Milward Simpson Administrator, Division of Cultural Resources Sara E. Needles State Historic Preservation Ocer Mary M. Hopkins Compiled and Edited by: Judy K. Wolf Chief, Planning and Historic Context Development Program Published by: e Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Wyoming State Historic Preservation Oce Barrett Building 2301 Central Avenue Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002 City County Building (Casper - Natrona County), a Public Works Administration project. Photograph by Richard Collier. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................5 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................6 Letter from Governor Matthew H.