Association Between Rs2303861 Polymorphism in CD82 Gene and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: a Preliminary Case-Control Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viewed Under 23 (B) Or 203 (C) fi M M Male Cko Mice, and Largely Unaffected Magni Cation; Scale Bars, 500 M (B) and 50 M (C)

BRIEF COMMUNICATION www.jasn.org Renal Fanconi Syndrome and Hypophosphatemic Rickets in the Absence of Xenotropic and Polytropic Retroviral Receptor in the Nephron Camille Ansermet,* Matthias B. Moor,* Gabriel Centeno,* Muriel Auberson,* † † ‡ Dorothy Zhang Hu, Roland Baron, Svetlana Nikolaeva,* Barbara Haenzi,* | Natalya Katanaeva,* Ivan Gautschi,* Vladimir Katanaev,*§ Samuel Rotman, Robert Koesters,¶ †† Laurent Schild,* Sylvain Pradervand,** Olivier Bonny,* and Dmitri Firsov* BRIEF COMMUNICATION *Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology and **Genomic Technologies Facility, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; †Department of Oral Medicine, Infection, and Immunity, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; ‡Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry, St. Petersburg, Russia; §School of Biomedicine, Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia; |Services of Pathology and ††Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University Hospital of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; and ¶Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France ABSTRACT Tight control of extracellular and intracellular inorganic phosphate (Pi) levels is crit- leaves.4 Most recently, Legati et al. have ical to most biochemical and physiologic processes. Urinary Pi is freely filtered at the shown an association between genetic kidney glomerulus and is reabsorbed in the renal tubule by the action of the apical polymorphisms in Xpr1 and primary fa- sodium-dependent phosphate transporters, NaPi-IIa/NaPi-IIc/Pit2. However, the milial brain calcification disorder.5 How- molecular identity of the protein(s) participating in the basolateral Pi efflux remains ever, the role of XPR1 in the maintenance unknown. Evidence has suggested that xenotropic and polytropic retroviral recep- of Pi homeostasis remains unknown. Here, tor 1 (XPR1) might be involved in this process. Here, we show that conditional in- we addressed this issue in mice deficient for activation of Xpr1 in the renal tubule in mice resulted in impaired renal Pi Xpr1 in the nephron. -

Tfr2, Hfe, and Hjv in the Regulation of Body Iron Homeostasis

TFR2, HFE, AND HJV IN THE REGULATION OF BODY IRON HOMEOSTASIS By Christal Anna Worthen A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Cell & Developmental Biology and the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 School of Medicine Oregon Health & Science University CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ___________________________________ This is to certify that the PhD dissertation of Christal A Worthen has been approved ______________________________________ Caroline Enns, Ph.D., mentor ______________________________________ Peter Mayinger, Ph.D., Chairman ______________________________________ Philip Stork, M.D. ______________________________________ David Koeller, M.D. ______________________________________ Alex Nechiporuk, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS i List of Figures ii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations v Abstract: 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 5 Abstract and Introduction 6 Binding partners, regulation, and trafficking of TFR2 9 Disease-causing mutations in TFR2 12 Hepcidin regulation 12 Physiological function of TFR2 15 Current TFR2 models 18 Summary 19 Figure 21 Chapter 2: The cytoplasmic domain of TFR2 is necessary for 22 HFE, HJV, and TFR2 regulation of hepcidin Abstract 23 Capsule & Introduction 24 Materials and Methods 26 Results 32 Figures 41 Discussion 49 Chapter 3: Lack of functional TFR2 results in stress erythropoiesis 53 Introduction 54 Materials and Methods 55 Results 57 Figures 60 Discussion 65 Chapter 4: Conclusions and future directions 67 Appendices Appendix A: Coculture of HepG2 cells reduces hepcidin expression 71 Appendix B: Hfe-/- macrophages handle iron differently 80 Appendix C: Both ZIP14A and ZIP14B are regulated by HFE and iron 91 Appendix D: The cytoplasmic domain of HFE does not interact with 99 ZIP14 loop 2 by yeast-2-hybris References 105 i LIST OF FIGURES Figure Abstract 1: Body iron homeostasis. -

2013 New Molecular CPT Co

Cleveland Clinic Laboratories 2013 New Molecular CPT Codes 2013 Test Name Order Code Billing Code CPT Codes 2012 CPT Codes ACADM PCR, Complete, Tier 2 ACADM 88175 81404 83891, 83894x10, 83898x10, 83904x20 ACTA2 Gene Sequencing ACTA2 88528 81403 83898x9, 83904x9, 83891 ADmark ApoE Genotype (Symptomatic) APOALZ 82397 81401 83892, 83894, 83898, 81401, 83891 ADmark PS-1 Analysis, Symptomatic PS1SY 83019 81405 83904x10, 83909x10, 83898x10, 83891 Alpha Globin (HBA1 and HBA2) Sequencing HBA12 88847 81257 New test in 2013 Alpha Thalassemia Gene Deletion ATHAL 84123 81257 83891, 83900, 83901x8, 83894 Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Quantitation and Phenotyping PHA1A 84187 81332 82103, 82104 Angelman UBE3A Sequencing UBE3A 88200 81331 83898x8, 83904x10, 83909x10 APO E Genotype APOEG 79374 81401 83891, 81401, 83898, 83896x2 ARX Sequence Analysis ARXSEQ 87860 81404 83890, 83898x5, 83894, 83904x6 Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Evaluation AIRE 83293 81479 83909x14, 83891, 83898x14, 83904x14 Autosomal Dom Ataxia Evaluation AUTOAT 82179 81401, 83909x88, 83898x88, 83904x77, 81479x13 83891 Barth Syndrome, Carrier BARCAR 82536 81406 83891, 83898, 83904x2 Barth Syndrome, Initial Patient BARINI 82535 81406 83891, 83898, 83904x9 Bartonella PCR, Tissue TBART 87924 87471 83898x4, 83890, 83894 B-Cell Clonality Using BIOMED-2 PCR Primers BCBMD 87904 81261, 83891, 83900, 83909x5, 83898x3, 83901x2, 81264 83912, 81261, 81264 BCL 2 mbr (PCR) BCL2 81099 81401 81401, 83890, 83898, 83894, 83912 BCR/ABL Kinase Domain Mutation Analysis KINASE 84529 81403 83891, 83898, 83902, 83904x4, -

Pathological Relationships Involving Iron and Myelin May Constitute a Shared Mechanism Linking Various Rare and Common Brain Diseases

Rare Diseases ISSN: (Print) 2167-5511 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/krad20 Pathological relationships involving iron and myelin may constitute a shared mechanism linking various rare and common brain diseases Moones Heidari, Sam H. Gerami, Brianna Bassett, Ross M. Graham, Anita C.G. Chua, Ritambhara Aryal, Michael J. House, Joanna F. Collingwood, Conceição Bettencourt, Henry Houlden, Mina Ryten , John K. Olynyk, Debbie Trinder, Daniel M. Johnstone & Elizabeth A. Milward To cite this article: Moones Heidari, Sam H. Gerami, Brianna Bassett, Ross M. Graham, Anita C.G. Chua, Ritambhara Aryal, Michael J. House, Joanna F. Collingwood, Conceição Bettencourt, Henry Houlden, Mina Ryten , John K. Olynyk, Debbie Trinder, Daniel M. Johnstone & Elizabeth A. Milward (2016) Pathological relationships involving iron and myelin may constitute a shared mechanism linking various rare and common brain diseases, Rare Diseases, 4:1, e1198458, DOI: 10.1080/21675511.2016.1198458 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21675511.2016.1198458 © 2016 The Author(s). Published with View supplementary material license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC© Moones Heidari, Sam H. Gerami, Brianna Bassett, Ross M. Graham, Anita C.G. Chua, Ritambhara Aryal, Michael J. House, Joanna Accepted author version posted online: 22 Submit your article to this journal JunF. Collingwood, 2016. Conceição Bettencourt, PublishedHenry Houlden, online: Mina 22 Jun Ryten, 2016. for the UK Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC), John K. Olynyk, Debbie Trinder, Daniel M. Johnstone,Article views: and 541 Elizabeth A. Milward. View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=krad20 Download by: [University of Newcastle, Australia] Date: 17 May 2017, At: 19:57 RARE DISEASES 2016, VOL. -

Genetic Testing Guidelines

GUIDELINE Genetic Testing Guidelines Categories This Guideline Applies To: Clinical Care Management CM, TCHP Texas Children's Health Plan Guidelines, Utilization Management UM Guideline # 6181 Document Owner Bhavana Babber GUIDELINE STATEMENT: Texas Children's Health Plan (TCHP) performs authorization of genetic testing requests. PRIOR AUTHORIZATION GUIDELINES 1. Genetic testing conducted by out-of-network providers will be treated as out-of-network requests and will comply with the out-of-network authorization Guidelines. 2. Requests for Noninvasive Prenatal Testing will comply with TCHP Noninvasive Prenatal Testing Guidelines. 3. All requests for prior authorization for genetic testing are received via fax, phone or mail by the Utilization Management Department and processed during normal business hours. 4. The Utilization Management professional receiving the request evaluates the submitted information to determine if the documentation supports the genetic testing as an eligible service. 5. To request prior authorization for genetic testing, documentation supporting the medical necessity of the test requested must be provided. 6. TCHP will apply clinical criteria in the current Texas Medicaid Provider Manual (TMPPM) at the time of the request when applicable for the following: 6.1.BRCA gene mutation analysis 6.2.Genetic Testing for colorectal cancer 6.3.Cytogenetic testing 6.4.Pharmacogenetic Testing Version #: 5 Genetic Testing Guidelines Page 1 of 10 Printed copies are for reference only. Please refer to the electronic copy for the latest version. GUIDELINE 6.5. A request for retroactive authorization must be submitted no later than seven calendar days beginning the day after the lab draw is performed per TMPPM 7. Whole genome sequencing (code 81415) requires preauthorization on a case-by-case basis. -

Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Hfe Gene Expression

RUTE ISABEL PAULO MARTINS POST-TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION OF HFE GENE EXPRESSION LISBOA 2010 nº de arquivo “copyright” RUTE ISABEL PAULO MARTINS POST-TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION OF HFE GENE EXPRESSION Thesis presented to obtain the Ph.D. degree in Biology (Molecular Genetics), by the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia. LISBOA 2010 Agradecimentos Agradecimentos Ao concluir este trabalho gostaria de expressar o meu reconhecimento a todos aqueles que de algum modo contribuíram para a sua concretização. Esta tese de Doutoramento é o resultado de um trabalho de investigação realizado no Departamento de Genética do Instituto Nacional de Saúde Dr. Ricardo Jorge (INSA), em Lisboa, entre Janeiro de 2006 a Dezembro de 2009, onde foram disponibilizadas as condições essenciais para o seu desenvolvimento. Ao Presidente do Conselho Directivo do INSA, Professor Doutor José Pereira Miguel, manifesto o meu apreço. Agradeço à Doutora Maria Guida Boavida e ao Doutor João Lavinha por me terem recebido no então Centro de Genética Humana, permitindo a realização do meu trabalho, e por todo o interesse que demonstraram pelo mesmo. Este trabalho foi, na sua maioria, financiado pela Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia no âmbito do projecto de investigação PTDC/SAU/GMG/64494/2006, através do Programa de Financiamento Plurianual do Centro de Investigação em Genética Molecular Humana e sob a forma de uma Bolsa de Doutoramento com a referência SFRH/BD/21340/2005. À minha orientadora Doutora Paula Faustino estou reconhecida pela oportunidade inicial de me integrar no seu grupo de investigação, cujo acompanhamento ao longo destes oito anos tem sido crucial para a minha formação enquanto cientista. -

The Role of DMT1, Ferritin, and Transferrin Receptor in Schwann Cell Maturation and Myelination

9940 • The Journal of Neuroscience, December 11, 2019 • 39(50):9940–9953 Cellular/Molecular Iron Metabolism in the Peripheral Nervous System: The Role of DMT1, Ferritin, and Transferrin Receptor in Schwann Cell Maturation and Myelination X Diara A. Santiago Gonza´lez,* XVeronica T. Cheli,* Rensheng Wan, and XPablo M. Paez Hunter James Kelly Research Institute, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York 14203 Iron is an essential cofactor for many cellular enzymes involved in myelin synthesis, and iron homeostasis unbalance is a central component of peripheral neuropathies. However, iron absorption and management in the PNS are poorly understood. To study iron metabolism in Schwann cells (SCs), we have created 3 inducible conditional KO mice in which three essential proteins implicated in iron uptake and storage, the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), the ferritin heavy chain (Fth), and the transferrin receptor 1 (Tfr1), were postnatally ablated specifically in SCs. Deleting DMT1, Fth, or Tfr1 in vitro significantly reduce SC proliferation, maturation, and the myelination of DRG axons. This was accompanied by an important reduction in iron incorporation and storage. When these proteins were KO in vivo during the first postnatal week, the sciatic nerve of all 3 conditional KO animals displayed a significant reduction in the synthesis of myelin proteins and in the percentage of myelinated axons. Knocking out Fth produced the most severe phenotype, followed by DMT1 and, last, Tfr1. Importantly, DMT1 as well as Fth KO mice showed substantial motor coordination deficits. In contrast, deleting these proteins in mature myelinating SCs results in milder phenotypes characterized by small reductions in the percentage of myelinated axons and minor changes in the g-ratio of myelinated axons. -

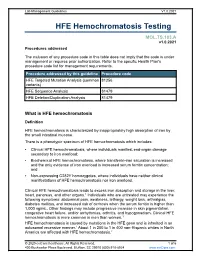

HFE Hemochromatosis Testing

Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2021 HFE Hemochromatosis Testing MOL.TS.183.A v1.0.2021 Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedure addressed by this guideline Procedure code HFE Targeted Mutation Analysis (common 81256 variants) HFE Sequence Analysis 81479 HFE Deletion/Duplication Analysis 81479 What is HFE hemochromatosis Definition HFE hemochromatosis is characterized by inappropriately high absorption of iron by the small intestinal mucosa. There is a phenotypic spectrum of HFE hemochromatosis which includes: Clinical HFE hemochromatosis, where individuals manifest end-organ damage secondary to iron overload; Biochemical HFE hemochromatosis, where transferrin-iron saturation is increased and the only evidence of iron overload is increased serum ferritin concentration; and Non-expressing C282Y homozygotes, where individuals have neither clinical manifestations of HFE hemochromatosis nor iron overload. Clinical HFE hemochromatosis leads to excess iron absorption and storage in the liver, heart, pancreas, and other organs.1 Individuals who are untreated may experience the following symptoms: abdominal pain, weakness, lethargy, weight loss, arthralgias, diabetes mellitus, and increased risk of cirrhosis when the serum ferritin is higher than 1,000 ng/mL. Other findings may include progressive increase in skin pigmentation, congestive heart failure, and/or arrhythmias, arthritis, and hypogonadism. Clinical HFE hemochromatosis is more common in men than women.1 HFE hemochromatosis is caused by mutations in the HFE gene and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.1 About 1 in 200 to 1 in 400 non-Hispanic whites in North America are affected with HFE hemochromatosis.2 © 2020 eviCore healthcare. -

Oral Administration of Ginger-Derived Lipid Nanoparticles and Dmt1

nutrients Article Oral Administration of Ginger-Derived Lipid Nanoparticles and Dmt1 siRNA Potentiates the Effect of Dietary Iron Restriction and Mitigates Pre-Existing Iron Overload in Hamp KO Mice Xiaoyu Wang 1,2,†, Mingzhen Zhang 3,4,† , Regina R. Woloshun 2, Yang Yu 2 , Jennifer K. Lee 2 , Shireen R. L. Flores 2, Didier Merlin 3,5 and James F. Collins 2,* 1 Key Laboratory of Precision Nutrition and Food Quality, College of Food Science and Nutritional Engineering, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] 2 Food Science & Human Nutrition Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA; regina.woloshun@ufl.edu (R.R.W.); yuyang2@ufl.edu (Y.Y.); leejennifer@ufl.edu (J.K.L.); srflores@ufl.edu (S.R.L.F.) 3 Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics, Institute for Biomedical Science, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30303, USA; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (D.M.) 4 School of Basic Medical Science, Health Science Center, Institute of Medical Engineering, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, China 5 Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, GA 30033, USA * Correspondence: jfcollins@ufl.edu Citation: Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; † These authors contributed equally to this work. Woloshun, R.R.; Yu, Y.; Lee, J.K.; Flores, S.R.L.; Merlin, D.; Collins, J.F. Abstract: Intestinal iron transport requires an iron importer (Dmt1) and an iron exporter (Fpn1). The Oral Administration of hormone hepcidin regulates iron absorption by modulating Fpn1 protein levels on the basolateral Ginger-Derived Lipid Nanoparticles surface of duodenal enterocytes. In the genetic, iron-loading disorder hereditary hemochromatosis and Dmt1 siRNA Potentiates the (HH), hepcidin production is low and Fpn1 protein expression is elevated. -

9092 Medical Single

Schedule of Accreditation issued by United Kingdom Accreditation Service 2 Pine Trees, Chertsey Lane, Staines-upon-Thames, TW18 3HR, UK Viapath Analytics LLP Issue No: 007 Issue date: 11 May 2021 Department of Haematological Contact: Nura Ibrahim Medicine Tel: +44 (0) 203 299 7685 Ground Floor Bessemer Wing E-Mail: [email protected] King's College Hospital 9092 Website: www.viapath.co.uk Denmark Hill Accredited to London ISO 15189:2012 SE5 9RS United Kingdom Testing performed at the above address only Site activities performed away from the locations listed above: Location details Activity King’s College Hospital (Denmark Hill): Storage & issue of blood & blood products only • Emergency Department • Liver Theatre • Neuro Theatre • Main Theatres • Nightingale Birth Centre (NBC) • Liver Unit ITU (LITU) • Centenary Wing • Harris Birthright (Windsor Walk) King’s College Hospital (Orpington Site): • Orthopaedic Theatres Assessment Manager: MS2 Page 1 of 22 Schedule of Accreditation issued by United Kingdom Accreditation Service 2 Pine Trees, Chertsey Lane, Staines -u po n - Thames, TW18 3HR, UK Viapath Analytics LLP 9092 Issue No: 007 Issue date: 11 May 2021 Accredited to ISO 15189:2012 Testing performed at main address only DETAIL OF ACCREDITATION Materials/Products tested Type of test/Properties Standard specifications/ measured/Range of measurement Equipment/Techniques used HUMAN TISSUES AND FLUIDS Cytogenetic analysis for the In house documented methods purpose of clinical diagnosis incorporating manufacturers’ instructions as required -

Hemochromatosis: Introduction

Hemochromatosis: Introduction Hemochromatosis was first identified in the 1800s, and by 1935 it was understood to be an inherited disease resulting in iron overload and deposition. Today, hemochromatosis is defined as a metabolic disorder affecting iron absorption , and resulting in the accumulation of excess iron in the body’s organs. Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is an autosomal recessive disorder that affects one in three hundred people in the United States. One in nine people carry the gene —making hemochromatosis the most common genetic disorder in the United States. It is primarily seen in middle-aged men of Northern European descent, and postmenopausal women. Treatment is readily available and the prognosis , with early diagnosis and proactive treatment, is a normal life expectancy. If untreated, hemochromatosis may lead to cirrhosis . Figure 1. Location of the liver in the body. What is Hemochromatosis? Despite being the most prevalent monoallelic genetic disease in Caucasians, hereditary hemochromatosis is under-diagnosed. There are several reasons for this, including lack of awareness, a long latency period, and nonspecific symptoms. Figure 2. Deposition of iron in the liver; A, Gross liver; B, Histological view. Normal iron absorption occurs in the proximal small intestine at a rate of 1-2 mg per day. In people with hereditary hemochromatosis, this absorption rate can reach 4–5 mg per day with progressive accumulation to 15–40 grams of iron in the body (Figure 2). Humans have no physiologic pathway to excrete iron. Therefore, iron can accumulate in any body tissue, although depositions are most common in the liver, thyroid, heart, pancreas, gonads, hypothalamus and joints. -

Hfe Gene Variants and Dysregulation of Cholesterol and Iron Metabolism in Alzheimer Disease and Cancer

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Medicine HFE GENE VARIANTS AND DYSREGULATION OF CHOLESTEROL AND IRON METABOLISM IN ALZHEIMER DISEASE AND CANCER A Dissertation in Molecular Medicine by Fatima Ghazanfar Ali-Rahmani © 2012 Fatima Ali-Rahmani Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 The dissertation of Fatima Ali-Rahmani was reviewed and approved* by the following: James R. Connor Distinguished Professor of Neurosurgery, Neural & Behavioral Sciences, and Pediatrics Vice Chair of Neurosurgery Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Cara-Lynne Schengrund Emeritus Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Ian Simpson Professor of Neural & Behavioral Sciences Patricia S. Grigson Professor of Neural & Behavioral Sciences Jong K. Yun Associate Professor of Pharmacology Co-chair of Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Molecular Toxicology Charles Lang Distinguished Professor of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, and Surgery Co-Chair, Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Molecular Medicine *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT Cholesterol and iron are essential for a number of cellular processes. Disruption of both cholesterol and iron metabolism have been independently reported to contribute to several diseases including Alzheimer disease (AD) and cancer. AD is a debilitating disease characterized by progressive neuronal loss and memory impairment. Although the underlying cause(s) of AD are not completely understood, iron accumulation and the resultant oxidative stress are well established contributors to the development of AD. Normal iron uptake is mediated by HFE (high iron, also called hemochromatosis protein). H63D and C282Y are two common variants of the HFE protein that are implicated as disease modifying risk factors for AD and several cancers, respectively.