The March 20, 2012, Ometepec, Mexico, Earthquake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

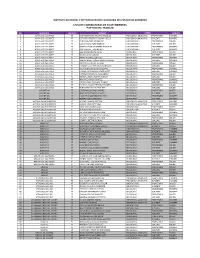

4. LISTA CANDIDATURAS PT.Xlsx

INSTITUTO ELECTORAL Y DE PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO LISTA DE CANDIDATURAS DE AYUNTAMIENTOS PARTIDO DEL TRABAJO NO. MUNICIPIO PARTIDO NOMBRE CARGO GÉNERO 1 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT IGOR ALEJANDRO AGUIRRE VAZQUEZ PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 2 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT OCTAVIO ROBERTO GALEANA BELLO PRESIDENCIA MUNICIPAL SUPLENTE HOMBRE 3 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT JENNY SANCHEZ RODRIGUEZ SINDICATURA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 4 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT KARLA PAOLA HARO MARCIAL SINDICATURA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 5 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT ROBERTO CARLOS ORTEGA GONZALEZ SINDICATURA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 6 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT JOSÉ MANUEL LEON BRUNO SINDICATURA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 7 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT ANA IRIS MENDOZA NAVA REGIDURIA 1 PROPIETARIA MUJER 8 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAYRA LEON CASIANO REGIDURIA 1 SUPLENTE MUJER 9 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MARIO ALONSO QUEVEDO REGIDURIA 2 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 10 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT SANTOS ANGEL TOMAS ANALCO RAMOS REGIDURIA 2 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 11 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT LILIANA ESTEVEZ DE LA ROSA REGIDURIA 3 PROPIETARIA MUJER 12 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT DANELLY ESTEFANY ROMERO NAJERA REGIDURIA 3 SUPLENTE MUJER 13 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT REGINALDO LARREA BALTODANO REGIDURIA 4 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE 14 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT CARLOS ALEJANDRO CHAVEZ LOPEZ REGIDURIA 4 SUPLENTE HOMBRE 15 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT DAYANA YIZEL NAVA AVELLANEDA REGIDURIA 5 PROPIETARIA MUJER 16 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAYRA LUCILA CADENA AGUILAR REGIDURIA 5 SUPLENTE MUJER 17 ACAPULCO DE JUÁREZ PT MAURICIO SUAZO BENITEZ REGIDURIA 6 PROPIETARIO HOMBRE -

GPS Constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec Earthquake Sequence, Southern Mexico: Coseismic and Post-Seismic Deformation

Portland State University PDXScholar Geology Faculty Publications and Presentations Geology 10-2014 GPS Constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec Earthquake Sequence, Southern Mexico: Coseismic and Post-Seismic Deformation Shannon E. Graham University of Wisconsin - Madison Charles DeMets University of Wisconsin - Madison Enrique Cabral-Cano Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico Vladimir Kostoglodov Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico Andrea Walpersdorf Universite de Grenoble See next page for additional authors Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/geology_fac Part of the Geology Commons, and the Geophysics and Seismology Commons Citation Details Graham, S. E., DeMets, C., Cabral-Cano, E., Kostoglodov, V., Walpersdorf, A., Cotte, N., & ... Salazar-Tlaczani, L. (2014). GPS constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec earthquake sequence, southern Mexico: coseismic and post-seismic deformation. Geophysical Journal International, 199(1), 200-218. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Shannon E. Graham, Charles DeMets, Enrique Cabral-Cano, Vladimir Kostoglodov, Andrea Walpersdorf, Nathalie Cotte, Michael Brudzinski, Robert McCaffrey, and Luis Salazar-Tlaczani This article is available at PDXScholar: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/geology_fac/52 Geophysical Journal International Geophys. J. Int. (2014) 199, 200–218 doi: 10.1093/gji/ggu167 GJI Geodynamics and tectonics GPS constraints on the Mw = 7.5 Ometepec earthquake sequence, southern Mexico: coseismic and post-seismic deformation Shannon E. Graham,1 Charles DeMets,1 Enrique Cabral-Cano,2 Vladimir Kostoglodov,2 Andrea Walpersdorf,3 Nathalie Cotte,3 Michael Brudzinski,4 Robert McCaffrey5 and Luis Salazar-Tlaczani2 1Department of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA. -

Directorio De Oficialías Del Registro Civil

DIRECTORIO DE OFICIALÍAS DEL REGISTRO CIVIL DATOS DE UBICACIÓN Y CONTACTO ESTATUS DE FUNCIONAMIENTO POR EMERGENCIA COVID19 CLAVE DE CONSEC. MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE OFICIALÍA NOMBRE DE OFICIAL En caso de ABIERTA o PARCIAL OFICIALÍA DIRECCIÓN HORARIO TELÉFONO (S) DE CONTACTO CORREO (S) ELECTRÓNICO ABIERTA PARCIAL CERRADA Días de atención Horarios de atención 1 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ ACAPULCO 1 ACAPULCO 09:00-15:00 SI CERRADA CERRADA LUNES, MIÉRCOLES Y LUNES-MIERCOLES Y VIERNES 9:00-3:00 2 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ TEXCA 2 TEXCA FLORI GARCIA LOZANO CONOCIDO (COMISARIA MUNICIPAL) 09:00-15:00 CELULAR: 74 42 67 33 25 [email protected] SI VIERNES. MARTES Y JUEVES 10:00- MARTES Y JUEVES 02:00 OFICINA: 01 744 43 153 25 TELEFONO: 3 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ HUAMUCHITOS 3 HUAMUCHITOS C. ROBERTO LORENZO JACINTO. CONOCIDO 09:00-15:00 SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-05:00 01 744 43 1 17 84. CALLE: INDEPENDENCIA S/N, COL. CENTRO, KILOMETRO CELULAR: 74 45 05 52 52 TELEFONO: 01 4 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ KILOMETRO 30 4 KILOMETRO 30 LIC. ROSA MARTHA OSORIO TORRES. 09:00-15:00 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-04:00 TREINTA 744 44 2 00 75 CELULAR: 74 41 35 71 39. TELEFONO: 5 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PUERTO MARQUEZ 5 PUERTO MARQUEZ LIC. SELENE SALINAS PEREZ. AV. MIGUEL ALEMAN, S/N. 09:00-15:00 01 744 43 3 76 53 COMISARIA: 74 41 35 [email protected] SI LUNES A DOMINGO 09:00-02:00 71 39. 6 ACAPULCO DE JUAREZ PLAN DE LOS AMATES 6 PLAN DE LOS AMATES C. -

A Sleeping Giant Stirs: Mexico'S

A Sleeping Giant Stirs: Mexico's October Risings Largely downplayed in the U.S. media, ground-shaking events are rattling Mexico. On one key front, Mexican Interior Minister Miguel Angel Osorio Chong announced October 3 the Pena Nieto administration’s acceptance of many of the demands issued by striking students of the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN). IPN Director Yoloxichitl Bustamante, whose ouster had been demanded by the students, handed in her resignation. Osorio Chong’s words were delivered to thousands of students from an improvised stage outside Interior Ministry headquarters in Mexico City. In addition to Bustamante’s departure, the senior Pena Nieto cabinet official pledged greater resources for the IPN, the cancellation of administrative and academic changes opposed by the students, the prohibition of lifetime pensions for IPN directors, the replacement of a much-criticized campus police force, and no retaliations against the strikers. Osorio Chong shared the students’ concerns that IPN policies were turning a professional education into an assembly-line diploma mill and reducing “the excellence of schools of higher education.” Education Secretary Emilio Chuayfett was noticeably absent for Osorio Chong’s presentation, which was held at the conclusion of a Friday afternoon march through the Mexican capital that attracted in upwards of 20,000 students. Distrustful of the government, the students are reacting cautiously to the Pena Nieto administration’s response to their 10-point petition, insisting among other things that Yolo Bustamante be held accountable for alleged transgressions before leaving her job. Student activists said that acceptance of the government’s response will be democratically debated and resolved at upcoming meetings of the 44 schools that form the IPN. -

Secretaria De Desarrollo Social

Jueves 11 de octubre de 2007 DIARIO OFICIAL (Primera Sección) SECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL ACUERDO de Coordinación para la asignación y operación de los subsidios del Programa Hábitat, Vertiente General del Ramo Administrativo 20 Desarrollo Social, que suscriben la Secretaría de Desarrollo Social, el Estado de Guerrero y los municipios de Acapulco de Juárez, Atoyac de Alvarez, Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Coyuca de Benítez, Eduardo Neri, Huitzuco de los Figueroa, Iguala de la Independencia, José Azueta, Ometepec, Petatlán, Pungarabato, Taxco de Alarcón, Teloloapan, Tixtla de Guerrero y Tlapa de Comonfort de dicha entidad federativa. Al margen un sello con el Escudo Nacional, que dice: Estados Unidos Mexicanos.- Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. ACUERDO DE COORDINACION PARA LA ASIGNACION Y OPERACION DE LOS SUBSIDIOS DEL PROGRAMA HABITAT, VERTIENTE GENERAL, DEL RAMO ADMINISTRATIVO 20 “DESARROLLO SOCIAL”, QUE SUSCRIBEN POR UNA PARTE EL EJECUTIVO FEDERAL, A TRAVES DE LA SECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO SOCIAL, EN LO SUCESIVO “LA SEDESOL”, REPRESENTADA EN ESTE ACTO POR LA SUBSECRETARIA DE DESARROLLO URBANO Y ORDENACION DEL TERRITORIO, ARQ. SARA HALINA TOPELSON FRIDMAN, ASISTIDA POR EL DELEGADO DE LA SEDESOL EN EL ESTADO DE GUERRERO C. DR. JOSE IGNACIO ORTIZ UREÑA; POR OTRA PARTE, EL EJECUTIVO DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, EN LO SUCESIVO “EL ESTADO” REPRESENTADO POR EL SECRETARIO DE DESARROLLO URBANO Y OBRAS PUBLICAS; EL COORDINADOR GENERAL DEL EJECUTIVO ESTATAL Y COORDINADOR GENERAL DEL COMITE DE PLANEACION PARA EL DESARROLLO DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO Y EL COORDINADOR GENERAL ADJUNTO DEL COMITE DE PLANEACION PARA EL DESARROLLO DEL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, LOS CC. ARQ. GUILLERMO TORRES MADRID, LIC. HUMBERTO SARMIENTO LUEBBERT; Y LIC. -

Escuela Nacional De Antropología E Historia

ESCUELA NACIONAL DE ANTROPOLOGÍA E HISTORIA. ETNOHISTORY. SYMPOSIAST: FLOR YENIN CERON ROJAS. GRADUATE STUDENT, B.A. PROGRAM IN ETHNOHISTORY. SYMPOSIUM: STUDIES ABOUT OAXACA AND NEIGHBORING AREAS (continuation). COORDINATOR: LAURA RODRÍGUEZ CANO, M.A. ABSTRACT: The following paper is a first attempt to know which are the boundaries shared by the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero, as well as which communities from both states have had conflicts and which are the different ways of naming these boundaries. The ultimate goal is to know in greater depth the relationships that existed in the past between the communities of Oaxaca and Guerrero. This analysis is based on a book from the 19th century entitled Arbitraje sobre los límites territoriales entre los estados de Guerrero y Oaxaca [arbitration on the territorial boundaries between the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca], a document kept in the National Library (reserved section). “An approximation to the geopolitical analysis of the boundaries between Guerrero and Oaxaca” The book called Arbitraje pronunciado por el general Mucio P. Martínez sobre los límites territoriales entre los estados de Guerrero y Oaxaca [Arbitration given by general Mucio P. Martínez about the territorial boundaries between the states of 1 Guerrero and Oaxaca] was published in Puebla in 1890F F. This is a document dealing with the technical and legal process of revising the boundaries that form the dividing line between the states named above. This process was undertaken in the last two decades of the 19th century. 1 This book is in the National Library of Mexico in the collection of reserved access. Figure 1. -

Zirandaro”, Ubicado En El Km

MANIFESTACION DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD REGIONAL ESTUDIOS Y PROYECTOS DEL PUENTE “ZIRANDARO”, UBICADO EN EL KM. 0+200 S/C ZIRANDARO ESTADO DE GUERRERO – LA ERA ESTADO DE MICHOACÁN I. DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO, DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL I.1. DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO 1. Clave del proyecto 2. Nombre del proyecto ESTUDIOS Y PROYECTOS DEL PUENTE “ZIRANDARO”, UBICADO EN EL KM. 0+200 S/C ZIRANDARO ESTADO DE GUERRERO – LA ERA ESTADO DE MICHOACÁN. 3. Datos del sector y tipo de proyecto 3.1 Sector Vías Generales de Comunicación. 3.2 Subsector Infraestructura Carretera 3.3 Tipo de proyecto Carretera Federal 4. Estudio de riesgo y su modalidad No aplica 5. Ubicación del proyecto 5.1. Calle y número, o bien nombre del lugar y/o rasgo geográfico de referencia, en caso de carecer de dirección postal Este estudio corresponde a la Manifestación de Impacto Ambiental por la construcción de un Puente Vehicular, por lo que no tiene una dirección postal, sin embargo se presenta un croquis de localización y en el punto 5.6 de este mismo capítulo, se presentan las coordenadas de los puntos de inflexión de la carretera. 5.2. Código postal No aplica 5.3. Entidad federativa Estado de Guerrero 5.4. Municipio(s) o delegación(es) Zirandaro 5.5. Localidad(es) Zirandaro, Gro. y La Era, MIch. Desarrollos Integrales de Ingeniería, S.A. de C.V. Capítulo I - 1 MANIFESTACION DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD REGIONAL ESTUDIOS Y PROYECTOS DEL PUENTE “ZIRANDARO”, UBICADO EN EL KM. 0+200 S/C ZIRANDARO ESTADO DE GUERRERO – LA ERA ESTADO DE MICHOACÁN Fuente: Mapa General del Estado. -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Ometepec, Guerrero

Informe Anual Sobre La Situación de Pobreza y Rezago Social Ometepec, Guerrero I. Indicadores sociodemográficos II. Medición multidimensional de la pobreza Ometepec Guerrero Indicador Indicadores de pobreza y vulnerabilidad (porcentajes), (Municipio) (Estado) 2010 Población total, 2010 61,306 3,388,768 Total de hogares y viviendas 13,328 805,230 Vulnerable por particulares habitadas, 2010 carencias social Tamaño promedio de los hogares 4.64.2 5.1 0.7 (personas), 2010 28.7 Vulnerable por Hogares con jefatura femenina, 2010 3,353216,879 ingreso Grado promedio de escolaridad de la 75.4 No pobre y no 77.3 18.8 población de 15 o más años, 2010 46.7 vulnerable Total de escuelas en educación básica y 207 10,975 Pobreza moderada media superior, 2010 Personal médico (personas), 2010 93 4,825 Pobreza extrema Unidades médicas, 2010 17 1,169 Número promedio de carencias para la 4.03.4 población en situación de pobreza, 2010 Número promedio de carencias para la Indicadores de carencia social (porcentajes), 2010 población en situación de pobreza 4.44.1 82.7 extrema, 2010 78.5 80.2 Fuentes: Elaboración propia con información del INEGI y CONEVAL. 60.7 56.6 52.6 48.4 52.5 38.9 40.7 42.7 28.4 27.2 29.2 20.7 22.9 24.8 • La población total del municipio en 2010 fue de 61,306 15.2 personas, lo cual representó el 1.8% de la población en el estado. Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por • En el mismo año había en el municipio 13,328 hogares (1.7% rezago acceso a los acceso a la calidad y servicios acceso a la del total de hogares en la entidad), de los cuales 3,353 estaban educativo servicios de seguridad espacios de básicos en la alimentación encabezados por jefas de familia (1.5% del total de la entidad). -

Estado Municipio Guerrero

Estado Guerrero Municipio Cobertura Estatal Ejercicio 2015, Recursos 2015, Trimestre 4 Asignación FISE: 614,369,172 CONS. DESCRIPCIÓN NUM. PROY. ANUAL A_% EJERCIDO E_% U. MEDIDA POBLACIÓN M. ACUM. AVANCE Total 467,667,084 76.1% 369,593,355 60.2% 62,215 GRO15150400 1 Equipamiento Del Hospital General De Atoyac 5,000,000 0.8% - 0.0% Piezas - - 1.00 610421 Construcción De La Línea De Conducción Y Red De Distribución En La GRO15150100 2 Colonia Margarita Maza De Juárez En La Localidad De Ometepec Municipio 1,139,749 0.2% 1,120,890 0.2% Metros lineales - - 100.00 480271 De Ometepec Construcción De Comedor Comunitario En La Localidad Cerro Zacatón, GRO15150400 3 706,955 0.1% - 0.0% Metros Cuadrados - - 30.00 Municipio De Malinaltepec. 607778 Construcción Del Sistema De Agua Potable, Para Beneficiar A La Localidad GRO14140300 4 471,837 0.1% 442,127 0.1% Metros Cuadrados - - 93.70 De El Cascalote En El Municipio De Copalillo, Primera Etapa De Dos 368420 GRO15150200 5 Desarrollo De Zonas De Atencion Prioritarias Cochoapa El Grande 18,393,612 3.0% 18,393,612 3.0% Vivienda 1,850 - 100.00 534166 Construcción Del Sistema De Agua Potable En La Localidad De Atempa GRO15150100 6 816,073 0.1% - 0.0% Metros lineales 1,083 - - Municipio De Chilapa De Álvarez 475615 Ampliación De Red De Distribución Eléctrica En La Colonia Cazahuates, GRO15150400 7 2,021,963 0.3% - 0.0% Luminaria - - 70.00 Localidad De Zumpango Del Rio, Municipio De Eduardo Neri. 607659 Ampliación De Red De Distribución Eléctrica En La Calle Niño Perdido, GRO15150400 8 876,514 0.1% - 0.0% Luminaria - - 30.00 Colonia Ortiz, Localidad Xochihuetlán, Municipio De Xochihuetlán. -

Principales Resultados De La Encuesta Intercensal 2015. Guerrero

Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Guerrero Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Guerrero Obras complementarias publicadas por el INEGI sobre el tema: Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Catalogación en la fuente INEGI: 304.601072 Encuesta Intercensal (2015). Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 : Guerrero / Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía.-- México : INEGI, c2015. xiv, 97 p. ISBN 978-607-739-771-7 . 1. Guerrero - Población - Encuestas, 2015. I. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (México). Conociendo México 01 800 111 4634 www.inegi.org.mx [email protected] INEGI Informa @INEGI_INFORMA DR © 2016, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía Edificio Sede Avenida Héroe de Nacozari Sur 2301 Fraccionamiento Jardines del Parque, 20276 Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, entre la calle INEGI, Avenida del Lago y Avenida Paseo. de las Garzas. Presentación El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), como organismo autónomo responsable por ley de coordinar y dirigir el Sistema Nacional de Información Estadística y Geográfica, se encarga de producir y difundir información de interés nacional. Bajo esta premisa, en el 2015 se levanta una encuesta de cobertura temática amplia, denominada Encuesta Intercensal 2015, que tiene como objetivo generar información estadística actualizada sobre la población y las viviendas del territorio nacional, que mantenga la comparabilidad histórica con los censos y encuestas nacionales, así como con indicadores de otros países. Atendiendo a lo anterior, el INEGI ha puesto al alcance de todo públi- co algunos productos derivados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015, como: Microdatos, Tabulados básicos, Presentación de resultados y Panorama sociodemográfico de México 2015. -

Directorio De Oficinas De Sedes Auxiliares Regionales De La Oficina

Directorio de Oficinas de Sedes Auxiliares Regionales de la Oficina de Representación de la Coordinación Nacional de Becas para el Bienestar Benito Juárez en el Estado de Guerrero Prestadores de Servicios Profesionales por Honorarios Domicilio oficial: Primer Segundo Domicilio Domicilio Domicilio Domicilio Domicilio Domicilio Domicilio oficial: Nombre de la Nombre del apellido del apellido del oficial: Tipo de oficial: oficial: oficial: oficial: Tipo de oficial: Nombre del entidad Domicilio Denominación del servidor(a) servidor(a) servidor(a) vialidad Nombre de Número Número asentamiento Nombre del municipio o federativa oficial: Código Número(s) de Correo electrónico cargo público(a) público(a) público(a) (catálogo) vialidad Exterior interior (catálogo) asentamiento delegación (catálogo) postal teléfono oficial Extensión oficial, en su caso CAPTURISTA EN OSCAR LIBERATO LOPEZ Calle NIÑO S/N S/N Colonia LAZARO OMETEPEC Guerrero 41705 01 800 500 No aplica No aplica UNIDAD DE DAVID ARTILLERO CARDENAS 5050 ATENCIÓN REGIONAL RESPONSABLE EDREY PABLO BAUTISTA Calle JOSE MARIA 20 S/N Colonia BARRIO DE TIXTLA DE Guerrero 39174 01 800 500 No aplica No aplica EN ATENCIÓN A MORELOS Y SAN ISIDRO GUERRERO 5050 POBLACIÓN PAVON INDÍGENA. RESPONSABLE JUAN DANIEL CATALAN ANTONIO Pasaje CELESTE S/N S/N Colonia SAN DIEGO TLAPA DE Guerrero 41304 01 800 500 No aplica No aplica DE ATENCIÓN A COMONFORT 5050 RESPONSABLE PAMELA GUILLEN MARTINEZ Calle NIÑO S/N S/N Colonia LAZARO OMETEPEC Guerrero 41705 01 800 500 No aplica No aplica DE ATENCIÓN A ARTILLERO CARDENAS